Retrospecting the Collection Recontextualising Fragments of History and Memory Through the Alf Kumalo Museum Archive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utopia As a Perspective: Reading Historical Strata in Guy Tillim’S Documentary Photo Essay Jo’Burg Series

Utopia as a perspective: Reading historical strata in Guy Tillim’s documentary photo essay Jo’burg series Intern of Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography Miki Kurisu Utopia as a perspective: Reading historical strata in Guy Tillim’s documentary photo essay Jo’burg series Miki Kurisu 1. Introduction This essay examines the Jo’burg series by Guy Tillim (1962-) which represents a post-apartheid cityscape between 2003 and 2007. Born in Johannesburg in 1962, Guy Tillim started his professional career in 1986 and joined Afrapix, a collective photo agency strongly engaged with the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. He also worked for Reuters from 1986 to 1988 and then for Agence France Presse from 1993 to 1994. He has received numerous awards including Prix SCAM (2002), Higashikawa Overseas Photographer Award (2003), Daimler Chrysler Award for South African photography (2004) and Leica Oskar Barnack Award for his Jo’burg series. In addition, his works were ❖1 For Guy Tillim’s biography refer to ❖1 http://www.africansuccess.org/visuFiche. exhibited in both South Africa and Europe. The Jo’burg series highlights php?id=201&lang=en (Viewed on December 1st, 2013) Tillim’s critical approach to documentary photography in terms of subject matter, format and the portrayal of people. This series was chosen as an object of analysis out of other important works by equally significant South African photographers, such as Ernest Cole (1940-1990), Omar Badsha (1945-), David Goldblatt (1930-) and Santu Mofokeng (1956-) since the Jo’burg series enables us to follow the historical development of South African photography. -

Eastern Cape Kwazulu-Natal Indian Ocean Mpumalanga Limpopo North West Free State Northern Cape 19 21 23 22 01 02 04 Atlantic

GAUTENG @NelsonMandela Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory of Centre Mandela Nelson 08 16 05 10 12 15 Chancellor Nelson Mandela House Square www.southafrica.net | www.nelsonmandela.org The Nelson Mandela Memory of Centre Foundation’s Mandela Nelson the and Mandela House Liliesleaf Constitution Foundation’s Centre Museum Hill Tourism African South between effort joint a is initiative This of Memory 09 17 Hector Pieterson Sharpeville Human Museum Rights Precinct 06 11 13 07 14 18 Nelson Mandela Vilakazi Street Kliptown Apartheid Alexandra Nelson Mandela Statue at the Open-Air Museum Museum Heritage Precinct Bridge Union Buildings 18 JULY 1918 - Born Rolihlahla Mandela at MARCH 21 - Sharpeville Massacre Establishes the Nelson Mandela Children’s Mvezo in the Transkei Fund and donates one third of his 1918 1960 MARCH 30 - A State of Emergency is imposed 1995 presidential salary to it 1925 - Attends primary school near Qunu and Mandela is among thousands detained (receives the name ‘Nelson’ from a teacher) 1999 - Steps down after one term as APRIL 8 - The ANC is banned president, establishes the Nelson Mandela 1930 - Entrusted to Thembu Regent Foundation as his post-presidential office Jongintaba Dalindyebo 1961 - Goes underground; Umkhonto weSizwe (MK) is formed 2003 - Donates his prison number 46664 Africa. South 1934 - Undergoes initiation. Attends to a campaign to highlight the HIV/AIDS LIMPOPO Clarkebury Boarding Institute in Engcobo 1962, JANUARY 11 - Leaves the country for epidemic across Mandela Nelson about military training and to garner -

Between States of Emergency

BETWEEN STATES OF EMERGENCY PHOTOGRAPH © PAUL VELASCO WE SALUTE THEM The apartheid regime responded to soaring opposition in the and to unban anti-apartheid organisations. mid-1980s by imposing on South Africa a series of States of The 1985 Emergency was imposed less than two years after the United Emergency – in effect martial law. Democratic Front was launched, drawing scores of organisations under Ultimately the Emergency regulations prohibited photographers and one huge umbrella. Intending to stifle opposition to apartheid, the journalists from even being present when police acted against Emergency was first declared in 36 magisterial districts and less than a protesters and other activists. Those who dared to expose the daily year later, extended to the entire country. nationwide brutality by security forces risked being jailed. Many Thousands of men, women and children were detained without trial, photographers, journalists and activists nevertheless felt duty-bound some for years. Activists were killed, tortured and made to disappear. to show the world just how the iron fist of apartheid dealt with The country was on a knife’s edge and while the state wanted to keep opposition. the world ignorant of its crimes against humanity, many dedicated The Nelson Mandela Foundation conceived this exhibition, Between journalists shone the spotlight on its actions. States of Emergency, to honour the photographers who took a stand On 28 August 1985, when thousands of activists embarked on a march against the atrocities of the apartheid regime. Their work contributed to the prison to demand Mandela’s release, the regime reacted swiftly to increased international pressure against the South African and brutally. -

M************************************************W*************** Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 344 578 IR 015 527 AUTHOR Prinsloo, Jeanne, Ed.; Criticos, Costes, Ed. TITLE Media Matters in South Africa. Selected Papers Presented at the Conference on Developing Media Education in the 1990s (Durban, South Africa, September 11-13, 1990). INSTITUTION Natal Univ., Durban (South Africa). Media Resource Centre. REPORT NO ISBN-0-86980-802-8 PUB DATE 91 NOTE 296p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Conference Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Television; Elementary Secondary Education; Film Study; Foreign Countries; Higher Education; Instructional Films; *Instructional Materials; Mass Media Role; Media Research; *Media Selection; Teacher Education; Visual Literacy IDENTIFIERS *Media Education; *South Africa ABSTRACT This report contains a selection of contributed papers and presentations from a conference attended by 270 educators and media workers committed to formulate a vision for media education in South Africa. Pointing out that media education has been variously described in South Africa as visual literacy, mass media studies, teleliteracy, and film studies, or as dealing with educational technology or educational media, the introduction cites a definition of media education as an exploration of contemporary culture alongside more traditional literary texts. It is noted that this definition raises issues for education as a whole, for traditional language study, for media, for communication, and for u0erstanding the world. The 37 selected papers in this collection are presented in seven categories: (1) Why Media Education? (keynote paper by Bob Ferguson); (2) Matters Educational (10 papers on media education and visual literacy); (3) Working Out How Media Works (4 papers on film studies, film technology, and theory); (4) Creating New Possibilities for Media Awareness (9 papers on film and television and 4 on print media);(5) Training and Empowering (2 papers focusing on teachers and 4 focusing on training producers); (6) Media Developing Media Awareness (2 papers); and (7) Afterthoughts (I paper). -

Retrospecting the Collection Recontextualising Fragments of History and Memory Through the Alf Kumalo Museum Archive

Retrospecting the Collection Recontextualising fragments of history and memory through the Alf Kumalo Museum Archive Sanele Manqele 0612944k A dissertation in fulfilment of the Degree of Masters of Arts in Fine Arts (MAFA) at the University of Witwatersrand 2017 Supervisor: Rory Bester 2 I, the undersigned, hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously, in its entirety or in part, submitted it at any university for a degree. _________________________ ___________________________ Signature Date 3 Acknowledgements I would like to begin by thanking the central subject of this dissertation, Alf Kumalo. While I am not unhappy with any of my previous affirmations towards Bab Alf and his work (and there were many), it only goes without saying that this project would not have been possible without him. This paper is dedicated to an incredible contributor of South African history, one of the most influential people in African photojournalism, but more importantly to a photographer who gave his life capturing some of the most influential scenes in South African history. Bab Alf was a man of dignity, grace and who carried himself with an insurmountable kindness. I know that I am incredibly blessed to have met and worked with him, and that even the smallest contribution I can make is something to ensure that he is never forgotten. You are dearly missed Bab Alf. I would also like to send a very special thanks to a very exceptional supervisor, Dr Rory Bester. It has only been a pleasure to have been guided through this process by you. -

Legendary DRUM Photogra- Pher Jürgen Schadeberg, Who Now Lives in Spain, Talks to Us About His Memories of Madiba and Taking Ic

News THROUGH HIS LENS Legendary DRUM photogra- pher Jürgen Schadeberg, who now lives in Spain, talks to us about his memories of Madiba and taking iconic anti-apartheid photographs – a major part of the magazine’s legacy BY S’THEMBISO HLONGWANE PICTURES: ALEXANDER SNELLING CLAUDIA SCHADEBERG DRIVE through vast groves of infection and we wander down Jürgen’s fragrant olive and orange trees that memory lane of Madiba moments. seem to stretch to the horizon of “Whenever we met after he was released this beautiful part of Spain’s west from prison he would say to me, ‘How coast. I’d flown to the coastal city are you? Haven’t you retired yet?’ of Valencia and driven into the “Whenever Claudia and I went to Iinterior to the tiny village of Barx where Madiba for lunch he always asked me DRUM’s iconic former photographer why I wanted to visit an old man when Jürgen Schadeberg, who exposed the I probably had other more important iniquities of the apartheid regime through things to do.” the lens of his camera, lives with his wife Jürgen and Claudia smile at each Claudia. The searing 37 degree heat is a other. “Another memorable time was sharp contrast to the icy Joburg winter I’d when Claudia and I were invited to left behind 12 hours previously. Madiba’s Soweto house for a New Year’s I park the car on the steep driveway Eve party in 1991, his first since his of their comfortable two-storey villa, release,” Jürgen continues. which nestles among the foothills of an “We arrived early and sat on the imposing mountain range, and Jürgen terrace with Madiba chatting about the (82) comes out to welcome me. -

Portrait and Documentary Photography in Post-Apartheid South Africa: (Hi)Stories of Past and Present

Portrait and documentary photography in post-apartheid South Africa: (hi)stories of past and present Paula Alexandra Horta Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Cultural Studies at the University of London Centre for Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths College Supervision: Dr. Jennifer Bajorek 2011 Declaration This thesis is the result of work carried out by me, and has been written by me. Where other sources of information have been used, they have been acknowledged. Signed: ……………………………………………………… Date: ………………………………………………………… 2 Abstract This thesis will explore how South African portrait and documentary photography produced between 1994 and 2004 has contributed to a wider understanding of the country‘s painful past and, for some, hopeful, for others, bleak present. In particular, it will examine two South African photographic works which are paradigmatic of the political and social changes that marked the first decade after the fall of apartheid, focusing on the empowerment of both photographers and subjects. The first, Jillian Edelstein‘s (2001) Truth & Lies: Stories from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, captures the faces and records the stories of perpetrators and victims who gave their testimonies to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa from 1996 to 2000. The second, Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin‘s (2004a) Mr. Mkhize‟s Portrait & Other Stories from the New South Africa, documents the changed/ unchanged realities of a democratic country ten years after apartheid. The work of these photographers is showcased for its specificity, historicity and uniqueness. In both works the images are charged with emotion. Viewed on their own — uncaptioned — the photographs have the capacity to unsettle the viewer, but in both cases a compelling intermeshing of image and text heightens their resonance and enables further possibilities for interpretation. -

Nicolas Champeaux and Gilles Porte

ufo distribution presents a co-production of ufo production and rouge international SÉLECTION OFFICIELLE SÉANCE SPÉCIALE a film by nicolas champeaux and gilles porte france – 2018 – dcp – scope – colour – 5.1 – english (french sub-titles) – length : 1 h 4 6 DISTRIBUTION f R a N c e P R e ss F R a N c e int e rn a ti on a l s a l e S int e rn a ti on a l P R e ss UFO DISTRIBUTION Le bureaU De FloReNce Versatile RyaN WerneR 135, boulevard de Sébastopol Florence Narozny 06 86 50 24 51 23 rue Macé Cell: + 1 917 254 7653 75002 PARIS Clarisse André 06 70 24 05 10 4th floor - Cannes [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 01 55 28 88 95 [email protected] 33 (0)6 27 72 58 39 www.ufo-distribution.com www.florencenarozny.com OFFICIAL SCREENING PRESS SCREENING monday 14 may tuesday 15 mai 20:00 11:00 Salle du soixantième Salle Bazin SYNOPSIS 2018 marks the centenary of the birth of Nelson Mandela. He seized centre stage during a historic trial in 1963 and 1964. But there were eight others who, like him, faced the death sen- tence. They too were subjected to pitiless cross-examinations. To a man they stood firm and turned the tables on the state : South Africa’s Apartheid regime was in the dock. Recently recovered sound archives of those hearings transport us back into the thick of the courtroom battles. I N T E R V I E W W I T H THE DIRECTORS The State Against Nelson Mandela And The Others is based on the sound archives from the trial of Nelson Mandela and nine other men between 1963 and 1964. -

Ernest Cole 1940 – 1990

Notes on the Life of Ernest Cole 1940 – 1990 This book and exhibition are an attempt to construct a clear picture of Ernest Cole, a complex man whose work is little known, especially in his own country, but who deserves recognition as a major voice in the struggle against apartheid and as an original photographic artist. He was a determined, intelligent and skilful photographer with a special capacity for observation and an exceptional eye for capturing artistic, aesthetic and meaningful images even in the harshest and most threatening of situations. The main focus of Cole‟s photography was his commitment to humanity. From the late 1950s until 1966 he portrayed the everyday lives of black South Africans with warmth and empathy. As one of the most socially aware photographers of his time he left an insightful and comprehensive document of his people and their struggle. Many of the critical social documentary projects we know from the history of photography are characterized by the perspective of an outsider, looking obliquely in, or by somebody from a higher social class, looking down. This is the case in the early picture stories that became emblematic for photography as a weapon for creating change in society - from Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine, who both documented child labour during the first half of the 20th century - through the Farm Security Administration project in the USA during the 1930s, to contemporary documentation of the poor and those in underdeveloped countries. These photographers, temporarily visiting an environment, bring home material from an unknown reality, a reality that often shocks but also stimulates the curiosity of the viewer. -

Drum Man Bikitsha a Journalist Supreme

Drum Man Bikitsha A Journalist Supreme by James Tyhikile Matyu I WAS both devastated and saddened to learn of the demise at the weekend of one of the most illustrious black journalists ever produced by this country, Basil Sipho Neo Bridgeman Bikitsha, whom we affectionately called “Doc” or “Carcass”. He was one of the last few survivors of what we still proudly term the golden age of black journalism in South Africa in the ‘50s and ‘60s or the graduates of the Drum school of journalism. He was a product of an oppressive period in the political history of this country when there were no tertiary institutions to train black journalists and because of the racist laws of the country, white-owned newspapers wishing not to violate the Job Reservation Act didn‘t employ blacks as reporters. We two had made a promise to write each other‘s tribute, depending on who died first. Bikitsha, a graduate of Roma College in Lesotho, died at the age of 77 at the Tshepo Themba Clinic in Dobsonville, Soweto on Saturday night after he was admitted on December 26. I was fortunate enough to have rubbed shoulders in journalism with talented writers such as Bikitsha, Can Themba, Nat Nakasa, Dan Chocho, Casey Motsisi, Leslie Sehume, Obed Musi, Arthur Maimane, Sy Mogapi, Stan Motjuwadi, Theo Mthembu, Lewis Nkosi, Eskia Mphahlele, Harry Mashabela and many more who were in the forefront of recording the aspirations, the glory, the sufferings and triumphs of blacks. 1 I worked with Bikitsha for magazine and newspaper owner Jim Bailey at the Golden City Post and the Drum at Samkay House in Eloff Street towards the end of the ‘50s and into the ‘60s, where he became the right-hand man of assistant editor Themba. -

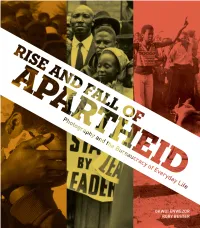

Rise and Fall of Apartheid

Events in the 1980s represent a significant coming to In light of these sweeping global changes, the scene in RISE AND FALL OF APARTHEID terms with the apartheid state at every level.8 It is within this Cape Town on that day in parliament can be properly encap- PHOTOGRAPHY AND THE BUREAUCRACY OF EVERYDAY LIFE context that the Detainees’ Hunger Strike at Diepkloof Prison sulated as an appointment with history. The announcement Okwui Enwezor in Soweto, which started on January 23, 1989, was pivotal in of the end of apartheid was part of a carefully choreographed F. W. de Klerk’s act of rapprochement that occurred a year lat- and coordinated plan: first the unbanning of the African Na- er. The strike appeared to be the trigger that finally brought tional Congress (ANC), Pan-African Congress (PAC), South Apartheid is Violence. Violence is used to subjugate and to deny basic rights to black people.1 But no matter how the policy of the apartheid government to the table for serious negotiation. African Communist Party (SACP), Congress of South African apartheid has been applied over the years, both black and white democrats have actively opposed it. It is in the struggle for Twenty prisoners detained under the 1986 state of emergen- Trade Unions (COSATU), and other political, labor, and civic justice that the gulf between artists, writers, and photographers and the people has been narrowed. cy laws began a hunger strike with an unequivocal demand: organizations; the lifting of the state of emergency; and the —Omar Badsha, South Africa: The Cordoned Heart, 1986 the unconditional release of all political prisoners. -

Jürgen Schadeberg's Work During the Fifties and Sixties and His Teaching Role in Drum

Inés Europa Crespo Esteso JÜRGEN SCHADEBERG’S WORK DURING THE FIFTIES AND SIXTIES AND HIS TEACHING ROLE IN DRUM JÜRGEN SCHADEBERG’S WORK DURING THE FIFTIES AND SIXTIES AND HIS TEACHING ROLE IN DRUM Inés Europa Crespo Esteso Bachelor Thesis Spring 2015 Visual Design Oulu University of Applied Sciences ABSTRACT Oulu University of Applied Sciences Visual Design Author: Inés Europa Crespo Esteso Title of thesis: Jürgen Schadeberg’s work during the fifties and sixties and his teaching role in Drum Supervisor: Heikki Timonen and Paco Castells Term and year when the thesis was submitted: Spring 2015 Number of pages: 45 This thesis introduces the reader to the concept of Documentary Photography and presents its earliest references on this field. The research also explores the most important facts and exponents of South African photography during the Apartheid period to end in the magazine Drum and in its first photographer and picture editor Jürgen Schadeberg. The aim of the thesis is that through the analysis of the documentary film that comes with the thesis, the reader will know about the figure of Jürgen Schadeberg and his work during the fifties and sixties. Just arrived from Germany, the young photographer landed in South Africa and saw the rise of Apartheid that brutally divided the population in blacks and whites. Eventually he started to work as a photographer for the magazine Drum, the only one aimed at the black population. Through Drum, Jürgen Schadeberg made a unique portrait of black society, its cultural events, its sports icons, its life and its political protests; it should be pointed out that no other publication captured the rise of the fight of the Anti-apartheid movement.