Conversation with Pierre Boulez - Paris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beata Kornatowska Wspomnienia Głosem Pisane : O Autobiografiach Śpiewaków

Beata Kornatowska Wspomnienia głosem pisane : o autobiografiach śpiewaków Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Litteraria Polonica 16, 140-154 2012 140 | FOLIA LITTERARIA POLONICA 2 (16) 2012 Beata Kornatowska Wspomnienia głosem pisane. O autobiografiach śpiewaków W literackim eseju Güntera de Bruyna poświęconym autobiografii czytamy: Opowiadający dokonuje pewnego okiełznania tego, co zamierza opowiedzieć, wtłacza to w formę, której wcześniej nie miało; decyduje o początku i zakończeniu, układa szczegóły [...] w wybranych przez siebie związkach, tak że nie są już tylko szczegółami, ale nabierają znaczenia, i określa punkty ciężkości1. Przy lekturze wspomnień znanych śpiewaków trudno oprzeć się wrażeniu, że przyszli na świat po to, żeby śpiewać. Już dobór wspomnień z dzieciństwa ma coś z myślenia magicznego: wydarzenia, sploty okoliczności, spotkania — wszystko to prowadzi do rozwoju kariery muzycznej. Dalsze powtarzalne elementy tych wspomnień to: odkrycie predyspozycji wokalnych i woli podję- cia zawodu śpiewaka, rola nauczycieli śpiewu i mentorów (najczęściej dyrygen- tów), największe sukcesy i zdobywanie kolejnych szczytów — scen kluczowych dla świata muzycznego, pamiętne wpadki, kryzysy wokalne, podszyte rywali- zacją relacje z kolegami, ciągłe podleganie ocenie publiczności, krytyków i dy- rygentów, myśli o konieczności zakończenia kariery, refleksje na temat doboru repertuaru, wykonawstwa i — generalnie — muzyki. W tle pojawiają się rów- nież wydarzenia z historii najnowszej, losy kraju i rodziny, kondycja instytucji muzycznych, uwarunkowania personalne. Te uogólnione na podstawie sporej liczby tekstów z niemieckiego kręgu ję- zykowego2 prawidłowości w organizowaniu wspomnień „głosem pisanych” chciałabym przedstawić na przykładzie wyróżniających się w mojej ocenie ja- kością autobiografii autorstwa ikon powojennej wokalistyki niemieckiej — Christy Ludwig ...und ich wäre so gern Primadonna gewesen. Erinnerungen („...a tak chciałam być primadonną. Wspomnienia”)3 i Dietricha Fischer-Dies- kaua Zeit eines Lebens. -

Contents: 1000 South Denver Avenue Suite 2104 Biography Tulsa, OK 74119 Critical Acclaim

Conductor Jack Price Managing Director 1 (310) 254-7149 Skype: pricerubin [email protected] Rebecca Petersen Executive Administrator 1 (916) 539-0266 Skype: rebeccajoylove [email protected] Olivia Stanford Marketing Operations Manager [email protected] Karrah O’Daniel-Cambry Opera and Marketing Manager [email protected] Mailing Address: Contents: 1000 South Denver Avenue Suite 2104 Biography Tulsa, OK 74119 Critical Acclaim Website: DIscography http://www.pricerubin.com Testimonials Indiana University Review Video LInks Complete artist information including video, audio and interviews are available at www.pricerubin.com Grzegorz Nowak – Biography Grzegorz Nowak is the Principal Associate Conductor of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in London. He has led the Orchestra on tours to Switzerland, Turkey and Armenia, as well as giving numerous concerts throughout the UK. His RPO recordings include Mendelssohn’s ‘Scottish’ and ‘Italian’ Symphonies, Shostakovich’s Symphony No.5, Dvořák’s Symphonies Nos. 6–9, all the symphonies of Schumann and complete symphonies and major orchestral works of Brahms and Tchaikovsky. He is also the Music Director & Conductor of the Orquesta Clásica Santa Cecilia and Orquesta Sinfonica de España in Madrid. Recordings of Grzegorz Nowak have been highly acclaimed by the press and public alike, winning many awards. Diapason in Paris praised his KOS live recording with Martha Argerich and Sinfonia Varsovia as ”indispensable…un must”, and its second edition won the Fryderyk Award. His recording of The Polish Symphonic Music of the XIX Century with Sinfonia Varsovia won the CD of the Year Award, the Bronze Bell Award in Singapore and Fryderyk Award nomination; the American Record Guide praised it as “uncommonly rewarding… 67 minutes of pure gold” and hailed his Gallo disc of Frank Martin with Biel Symphony as “by far the best”. -

DVORÁK of Eight Pieces for Piano Duet

GRZEGORZ NOWAK CONDUCTS DVO RÁK Symphonies no 6 - 9 Carnival Overture 3 CDs ˇ composer complied in 1878 with a set Symphony No.6 in D major, Op.60 the Vienna cancellation must have galled ANTONÍN DVORÁK of eight pieces for piano duet. These did the composer, was a resounding success. I. Allegro non tanto The work was published in Berlin in 1882 as (1841-1904) much to enhance his reputation abroad, II. Adagio and in 1884 he was invited to conduct ‘Symphony No.1’, ignoring the fact it actually III. Scherzo: Furiant-Presto had five symphonic predecessors, and leading his Stabat Mater in London, where his Antonín Dvorˇák was born in what was IV. Finale: Allegro con spirito to a situation where the celebrated work we music became immensely popular. In then known as Bohemia, in the small In the mid-1870s Dvorˇák, then in his now know as the Ninth appeared in print village of Mühlhausen, near Prague. 1891 he was made an honorary Doctor mid-thirties, was still struggling to gain as the Fifth. He was apprenticed as a butcher in of Music by Cambridge University and recognition and renown outside his native Dvorˇák’s earlier symphonies were strongly the following year made the first of his country. In 1874 he was awarded the first his father’s shop, encountering strong influenced by those of Beethoven. Indeed, visits to America, a country that would of several Austrian State Stipendium grants, paternal opposition to his intended his First Symphony, which was composed through which he made the acquaintance career as a musician. -

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

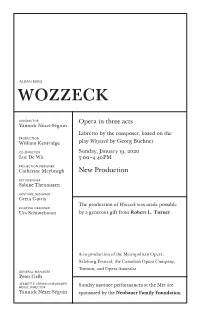

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J. -

Decca - Wiener Philharmoniker

DECCA - WIENER PHILHARMONIKER Vienna Holiday, Hans Knappertsbusch New Year Concert 1951, Hilde Gueden (soprano), Clemens Krauss, Josef Krips Overtures of Old Vienna, Willi Boskovsky New Year Concert 1979, Willi Boskovsky Adam: Giselle, Herbert von Karajan Bartók: Two Portraits Op. 5, The Miraculous Mandarin, Op. 19, Sz. 73 (complete ballet), Erich Binder (violin), Christoph von Dohnányi Beethoven: Symphony No. 1 in C major, Op. 21, Pierre Monteux Beethoven: Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 36, Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt Beethoven: Symphony No. 4 in B flat major, Op. 60, Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E flat major, Op. 55 'Eroica', Erich Kleiber Beethoven: Leonore Overture No. 2, Op. 72a, Leonore Overture No. 3, Op. 72b, Erich Kleiber Beethoven: Fidelio Overture Op. 72c, Clemens Krauss Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67, Sir Georg Solti, Beethoven: Symphony No. 7 in A major, Op. 92,. Sir Georg Solti Beethoven: Symphony No. 8 in F major, Op. 93, Claudio Abbado Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Op. 125 'Choral', Joan Sutherland (soprano), Marilyn Horne (contralto), James King (tenor), Martti Talvela (bass), Hans Schmidt- Isserstedt Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 1 in C Major, Op. 15, Friedrich Gulda (piano), Karl Böhm Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B flat major, Op. 19, Vladimir Ashkenazy (piano), Zubin Mehta Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 3 in C minor, Op. 37, Friedrich Gulda (piano), Horst Stein Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major, Op. 58, Friedrich Gulda (piano), Horst Stein Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 in E flat major, Op. 73 'Emperor', Clifford Curzon (piano), Hans Knappertsbusch Beethoven: String Quartet No. -

Memòria 11/12

MEMÒRIA GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU 2011-2012 G r a n T e a t r e d e l Liceu 11 Me /1 m ò ri a 2 Memòria 11/12 FuNdació GraN Teatre del Liceu ÍndEx ÍndICE ÒrgaNs de goverN 5 ÓrgaNos de gobierNo Programa de mecenatge 11 Programa de meceNazgo Temporada artística 17 Temporada artística Audiovisuals 205 Audiovisuales La institució 223 La iNstitucióN Altres líNies d’activitat 241 Otras liNeas de actividad Estadístiques 259 Estadísticas ÒrgaNs de goverN ÓrgaNos de gobierno Patronat de la Fundació 6 Patronato de la Fundación Comissió Executiva 7 Comisión Ejecutiva Comitè de Direcció 8 Comité de Dirección Consell d’Assessorament Artístic 9 Consejo de Asesoramiento Artístico PatroNat de la FuNdació PatroNato de la Fundación President Vocal representant de la Diputació de Barcelona Presidente Vocal representante de la Diputació de Barcelona José Manuel González LabRadoR (fins ARtuR Mas i GavarRó novembre de 2011) / Mònica QueRol i QueRol Vicepresidents Vocals representants de la Societat del Vicepresidentes Gran Teatre del Liceu MeRcedes ElviRa del Palacio Tascón (fins Vocales representantes de la Sociedad del desembre de 2011) / José Mª Lassalle Ruiz Gran Teatre del Liceu Jordi HeReu i BoheR (fins juliol de 2011) / Manuel BeRtRand i VeRgés JavieR Coll Olalla XavieR TRias i Vidal de LlobateRa José María CoRonas i GuinaRt Antoni Fogué i Moya (fins novembre de 2011) Manuel Busquet ARRufat / SalvadoR Esteve i FigueRas Vocals representants del Consell de Mecenatge Vocals representants de la Generalitat de Catalunya Vocales representantes del Consejo de Mecenazgo -

Centre D'art Santa Mònica, Barcelona) Dedicated to Pere Formiguera (Barcelona, 1952

224 CATALAN REVIEW Finally, l would like to note the exhibition Cmnos (Centre d'Art Santa Mònica, Barcelona) dedicated to Pere Formiguera (Barcelona, 1952). This exhibition focused on photographs taken by him of some thirty diHerent people at different stages during their life showing how they changed du ring a period of ten years (from 1991-2000). Those selected were of two adults and two children who are shown growing older through some 600 photographs. Valencia also oHered exhibitions of great interest. Above all, l would like to highlight the retrospective Ramon Goya, el pintor de las ciutats (IVAM, Valencia), and the avant-garde artist Antonio Ballester (Valencia, 19IO) (IVAM). l should not forget to mention two other exhibicions also at the IVAM: Pierre Alechinsky, the Belgian expressionist and founder member of the group Cobra, and the other, Roy Lichtenstein. In contrast, in Perpignan (Palau de Congressos Georges Pompidou), there was an important retrospective Aristides Maillol, whose sculptures were on show offering examples from all his periods, themes, formats and techniques used by this sculptor. ANNA BUTÍ (Translated by Roland Pearson) MUSIC In the area of symphonic and instrumental concerts, the prestigious Lorin Maazel conducted the London Philharmonic Orchestra in mid-July (1999) as part of the summer season of the Festival de Peralada. Moving on to the Fall season, at the end of October the Barcelona and National Catalonian Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Franz-Paul Decker with guest violinist Catherine Cho, interpreted a fairly surprising pro gram dedicated to Sir Edward EIgar (the emblematÏc representative of English Romantic Music) in the Auditori. -

Chan 9611 Book Cover.Qxd 17/10/07 1:10 Pm Page 1

Chan 9611 book cover.qxd 17/10/07 1:10 pm Page 1 Chan 9611(2) CHANDOS michael schønwandt CHAN 9611 BOOK.qxd 17/10/07 1:12 pm Page 2 Richard Strauss (1864–1949) Salome An opera in one act Libretto after Oscar Wilde’s poem of the same name AKG German translation by Hedwig Lachmann Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea ..................................................................................Reiner Goldberg tenor Herodias, Herod’s wife..........................................................................................................Anja Silja soprano Salome, Herodias’s daughter ............................................................................................Inga Nielsen soprano Jokanaan (John the Baptist)......................................................................................Robert Hale bass-baritone Narraboth, a young Syrian, Captain of the Guard ....................................................Deon van der Walt tenor Herodias’s Page............................................................................................Marianne Rørholm mezzo-soprano First Jew ................................................................................................................Gert Henning-Jensen tenor Second Jew ......................................................................................................................Ole Hedegaard tenor Third Jew ....................................................................................................................Mikael Kristensen tenor Fourth Jew -

Sir Colin Davis Discography

1 The Hector Berlioz Website SIR COLIN DAVIS, CH, CBE (25 September 1927 – 14 April 2013) A DISCOGRAPHY Compiled by Malcolm Walker and Brian Godfrey With special thanks to Philip Stuart © Malcolm Walker and Brian Godfrey All rights of reproduction reserved [Issue 10, 9 July 2014] 2 DDDISCOGRAPHY FORMAT Year, month and day / Recording location / Recording company (label) Soloist(s), chorus and orchestra RP: = recording producer; BE: = balance engineer Composer / Work LP: vinyl long-playing 33 rpm disc 45: vinyl 7-inch 45 rpm disc [T] = pre-recorded 7½ ips tape MC = pre-recorded stereo music cassette CD= compact disc SACD = Super Audio Compact Disc VHS = Video Cassette LD = Laser Disc DVD = Digital Versatile Disc IIINTRODUCTION This discography began as a draft for the Classical Division, Philips Records in 1980. At that time the late James Burnett was especially helpful in providing dates for the L’Oiseau-Lyre recordings that he produced. More information was obtained from additional paperwork in association with Richard Alston for his book published to celebrate the conductor’s 70 th birthday in 1997. John Hunt’s most valuable discography devoted to the Staatskapelle Dresden was again helpful. Further updating has been undertaken in addition to the generous assistance of Philip Stuart via his LSO discography which he compiled for the Orchestra’s centenary in 2004 and has kept updated. Inevitably there are a number of missing credits for producers and engineers in the earliest years as these facts no longer survive. Additionally some exact dates have not been tracked down. Contents CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF RECORDING ACTIVITY Page 3 INDEX OF COMPOSERS / WORKS Page 125 INDEX OF SOLOISTS Page 137 Notes 1. -

Retrats D'artistes De Cinema, Òpera I Ballet Col·Leccionats Per Joan Fosas

Retrats d’artistes de cinema, òpera i ballet col·leccionats per Joan Fosas Biblioteca de Catalunya. Unitat Gràfica, Fotografia Maig 2017 Informació relativa a la unitat documental Informació administrativa Dades biogràfiques Nota d’abast i contingut Llista de components Informació relativa a la unitat documental Creador: Biblioteca de Catalunya, Unitat Gràfica, Fotografia Títol: Retrats d’artistes de cinema, òpera i ballet col·leccionats per Joan Fosas Descripció física: 819 fotografies (amb 9 duplicats) Ubicació: Dipòsit de Reserva de la Unitat Gràfica Resum: Retrats d’actrius i actors cinematogràfics, cantants d’òpera i ballarins entre 1950 i 1990 Informació administrativa Procedència: Donatiu Núria Julià Fosas Restriccions de consulta o de reproducció Dades biogràfiques Joan Fosas i Carreras (Rubí 1937-2013) Ballarí, coreògraf i mestre de dansa i castanyoles, referent del món de la dansa tradicional catalana. Gràcies a ell s’han conservat moltes antigues danses que, d'altra manera, s'haurien perdut. Per aquest motiu el 2002 fou guardonat amb la Creu de Sant Jordi. Va estar vinculat bona part de la seva vida a l'Esbart Dansaire de Rubí, treballà també amb la companyia Danzares i el Ballet Español de la Habana i els darrers anys dirigia l'Esbart Santa Anna, de Les Escaldes (Andorra). Nota d’abast i contingut Entre les dècades del 1950 i el 1990 Llista de components A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z Nom Núm. Data Descripció Fotògraf Observ. Topogràfic fotos A Abbado, Roberto 1 Bust somrient. -

New Publications

NEW PUBLICATIONS BOOKS Fowler, Kenneth. Received Truths: Bertoli Brecht and the Problem of Gestus and Musical Meaning. New York: AMS Press, 1991. Richard, Lionel, ed. Berlin, 1919-1933: Gigantisme, crise sociale et avant garde: l'incarnation extreme de la modemite. [Paris): Editions Autrement, 1991. Sanders, Ronald. The Days Grow Short: The Life and Music ofKurt Weill. Los Angeles: Silman James Press, 1991. (Originally published by Holt, Rinehart& Winston in hardcover, 1980.) Stegmann, Vera Sonja. Das epische Musiktheater bei Strawinsky und Brecht. New York: P. Lang, 1991. ARTICLES Bernhart, Walter. "Zweimal 'Johnny': Der treulose Herzensbrecher bei Brecht/Weill und Auden/Britten." Musik und Unterricht. Zeitschrift fur Musikpiidagogik U/11 (November 1991): 34-40. Graepel, Jorg. "Composer in the Dark - Kurt Weill in Amerika, Tei) 2." Orpheus (October 1991): 13-16. Heinsen, Geerd. "Gertrude Lawrence. 'Moonlight is Silver': Kurt Weills Lady in the Dark." Orpheus (September 1991): 39-41. Krabbe. Niels. "Mahagonny hos BrechtogWei\l." Musik & Forskning 16 (1990-91): 69-144. Liu Shi-Rong (Director ofthe Artistic Committee ofthe Central OperaTheatre ofth e People's Republic of China). (Article in Chinese on Kurt Weill.] People's Music 4 (1991). Rehling, Eberhard. "Der Fall Hindemith." Motiv: Zeitschriftfiir Musik 1 Oanuary 1991): 25- 26. KOCH KURKA - ! Ill l,l l! lll ,1111111 It ,,111,1 , ... Schebera,Jtirgen. "KurtWeill als Galionsfigur." Motiv: Zeitschriftfiir Musik 1 Oanuary 1991): L 28-32. \I I I h"' ,, J RECORDINGS \\ , t I I Cabaret Songs by Schoenberg, Weill, Britten. Hanna Schaer, mezzo-soprano; Frans;ois Tillard, piano. L'Empreinte CD ED 13008. John Bunch Plays Kurt Weill. John Bunch, piano. -

Berg, Alban Wozzeck Op. 7 (1914-1921), Oper

Berg, Alban Wozzeck Op. 7 (1914-1921), Oper für Solisten, Chor und Orchester (4 Flöten [auch Piccoli], 4 Oboen [4. auch Englisch Horn], 4 Klarinetten, Bassklarinette, 3 Fagotte, Kontrafagott, 4 Hörner, 4 Trompeten, 4 Posaunen, Kontrabasstuba, 2 Paar Pauken, 1 Paar Becken, grosse Trommel, mehrere kleine Trommeln, Rute, grosses Tamtam, kleines Tamtam, Triangel, Xylophon, Celesta, Harfe, Streicher *Auf der Bühne: -Mehrere kleine Trommeln (I. Akt, 2. Szene) -Eine Militärmusik (1. Akt, 3. Szene): Piccolo, 2 Flöten, 2 Oboen, 2 Klarinetten, 2 Fagotte, 2 Hörner, 2 Trompeten, 3 Posaunen, Kontrabasstuba, Grosse Trommel mit Becken, kleine Trommel, Triangel) -Eine Heurigen- (Wirtshaus-) Musik (II. Akt, 4. Szene: 2 Fiedeln (um einen ganzen Ton höher gestimmte Geigen), Klarinette, Ziehharmonika bzw. Akkordeon, 2-4 Gitarren (unison), Bombardon (bzw. Basstuba) -Ein Pianino (III. Akt, 3. Szene) *Womöglich abgesondert vom grossen Orchester: -Ein Kammerorchester (II. Akt, 3. Szene) in der Besetzung von Arnold Schönbergs Kammersymphonie: Flöte (auch Piccolo), Oboe, Englischhorn, 2 Klarinetten, Bassklarinette, Fagott, Kontrafagott, 2 Hörner und ein Solo-Streichquintett. *Alle diese Ensembles können aus den Musikern des grossen Orchesters gebildet werden 3 Akte (15 Szenen) W Alma Maria Mahler zugeeignet Christoph Jäggin: CH-Gitarre ▼ Gesamtübersicht ▼ Literaturverzeichnis ▼ Register TEX Georg Büchner V 1) Wien: Universal Edition, U.E. 7379, 1955 (nach den hinterlassenen endgültigen Korrekturen des Komponisten, rev. v. H[ans] E[rich] Apostel) 2) Wien: Universal