13895 Wagner News

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ring Sample Lesson Plan: Wagner and Women **Please Note That This Lesson Works Best Post-Show

The Ring Sample Lesson Plan: Wagner and Women **Please note that this lesson works best post-show Educator should choose which female character to focus on based on the opera(s) the group has attended. See below for the list of female characters in each opera: Das Rheingold: Fricka, Erda, Freia Die Walküre: Brunhilde, Sieglinde, Fricka Siegfried: Brunhilde, Erda Götterdämmerung: Brunhilde, Gutrune GRADE LEVELS 6-12 TIMING 1-2 periods PRIOR KNOWLEDGE Educator should be somewhat familiar with the female characters of the Ring AIM OF LESSON Compare and contrast the actual women in Wagner’s life to the female characters he created in the Ring OBJECTIVES To explore the female characters in the Ring by studying Wagner’s relationship with the women in his life CURRICULAR Language Arts CONNECTIONS History and Social Studies MATERIALS Computer and internet access. Some preliminary resources listed below: Brunhilde in the “Ring”: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brynhildr#Wagner's_%22Ring%22_cycle) First wife Minna Planer: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minna_Planer) o Themes: turbulence, infidelity, frustration Mistress Mathilde Wesendonck: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mathilde_Wesendonck) o Themes: infatuation, deep romantic attachment that’s doomed, unrequited love Second wife Cosima Wagner: (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosima_Wagner) o Themes: devotion to Wagner and his works; Wagner’s muse Wagner’s relationship with his mother: (https://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/richard-wagner-392.php) o Theme: mistrust NATIONAL CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.7.9 STANDARDS/ Compare and contrast a fictional portrayal of a time, place, or character and a STATE STANDARDS historical account of the same period as a means of understanding how authors of fiction use or alter history. -

Jeudi 3 Juin 2021

ALDE jeudi 3 juin 2021 Musiques Archives et collection Jacques et Dominique Chailley 113 Expert François Roulmann 12 rue Beautreillis 75004 Paris 01 71 60 88 67 - 06 60 62 98 03 [email protected] Exposition à la Librairie Giraud-Badin à partir du lundi 19 avril de 9 h à 13 h et de 14 h à 18 h Sommaire À divers, en ordre chronologique de parution, de 1650 à 1978. nos 1 à 84 Archives Jacques Chailley. Collection musicale enrichie par son fils. nos 85 à 94 Collection musicale Jacques Chailley enrichie par son fils. Partitions et livres de théorie et d’histoire musicale avant 1800. nos 95 à 111 Motets, cantates, Noëls, airs, poësies et chansons... nos 112 à 125 Ouvrages et partitions romantiques, documentation jusqu’en 1914. nos 126 à 140 Partitions modernes, souvent dédicacées à Jacques Chailley. nos 141 à 162 Conditions de vente consultables sur www.alde.fr Honoraires de vente : 25% TTC En couverture : Lot n°12 et lot n°91. ALDE Maison de ventes spécialisée Livres - Autographes - Monnaies Musiques Archives et collection Jacques et Dominique Chailley 113 Vente aux enchères publiques Expert François Roulmann Jeudi 3 juin 2021 à 14 h 12 rue Beautreillis 75004 Paris 01 71 60 88 67 - 06 60 62 98 03 [email protected] Librairie Giraud-Badin 22, rue Guynemer 75006 Paris Tél. 01 45 48 30 58 Exposition à la Librairie Giraud-Badin à partir du lundi 19 avril de 9 h à 13 h et de 14 h à 18 h Commissaire-Priseur Sommaire Jérôme Delcamp À divers, en ordre chronologique de parution, de 1650 à 1978. -

Mahler, Petra Lang, Royal Concertgebouw

Mahler Symphony No. 3 / Bach Suite mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Symphony No. 3 / Bach Suite Country: Europe Released: 2004 Style: Romantic, Modern MP3 version RAR size: 1829 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1389 mb WMA version RAR size: 1509 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 858 Other Formats: RA XM ADX MMF ASF APE VOC Tracklist Symphony No. 3 In D Minor 1-1 1. Kräftig - Entschieden 35:00 1-2 2. Tempo Di Menuetto. Sehr Mäßig 9:44 1-3 3. Comodo. Scherzando. Ohne Hast 17:25 2-1 4. Sehr Langsam. Misterioso - 'o Mensch! Gib Acht!' 10:11 5. Lustig Im Tempo Und Keck Im Ausdruck - 'bimm Bamm. .Es 2-2 10:18 Sungen Drei Engel' 2-3 6. Langsam. Ruhevoll. Empfunden 23:10 Bach Suite (Arr. Mahler) 2-4 1. Overture 6:32 2-5 2. Rondeau - Badinerie 3:45 2-6 3 Air 5:06 2-7 4. Gavottes 1. And 2. 3:37 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Decca Music Group Limited Copyright (c) – Decca Music Group Limited Recorded At – Grote Zaal, Concertgebouw, Amsterdam Credits Arranged By – Gustav Mahler (tracks: 2-4 to 2-7) Choir – Netherlands Children's Choir (tracks: 1 to 2-3), Prague Philharmonic Choir* (tracks: 1 to 2-3) Composed By – Gustav Mahler (tracks: 1 to 2-3), Johann Sebastian Bach (tracks: 2-4 to 2-7) Conductor – Riccardo Chailly Edited By – Ian Watson , Jenni Whiteside Engineer – Andrew Hallifax (tracks: 1-1 to 2-3), Graham Meek (tracks: 2-4 to 2-7) Executive Producer – Andrew Cornall Liner Notes – Donald Mitchell Mezzo-soprano Vocals – Petra Lang (tracks: 1 to 2-3) Mixed By – Jonathan Stokes Orchestra – Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra* Notes - Recording dates: 5-9 May 2003 (Symphony No. -

Richard Strauss's Ariadne Auf Naxos

Richard Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos - A survey of the major recordings by Ralph Moore Ariadne auf Naxos is less frequently encountered on stage than Der Rosenkavalier or Salome, but it is something of favourite among those who fancy themselves connoisseurs, insofar as its plot revolves around a conceit typical of Hofmannsthal’s libretti, whereby two worlds clash: the merits of populist entertainment, personified by characters from the burlesque Commedia dell’arte tradition enacting Viennese operetta, are uneasily juxtaposed with the claims of high art to elevate and refine the observer as embodied in the opera seria to be performed by another company of singers, its plot derived from classical myth. The tale of Ariadne’s desertion by Theseus is performed in the second half of the evening and is in effect an opera within an opera. The fun starts when the major-domo conveys the instructions from “the richest man in Vienna” that in order to save time and avoid delaying the fireworks, both entertainments must be performed simultaneously. Both genres are parodied and a further contrast is made between Zerbinetta’s pragmatic attitude towards love and life and Ariadne’s morbid, death-oriented idealism – “Todgeweihtes Herz!”, Tristan und Isolde-style. Strauss’ scoring is interesting and innovative; the orchestra numbers only forty or so players: strings and brass are reduced to chamber-music scale and the orchestration heavily weighted towards woodwind and percussion, with the result that it is far less grand and Romantic in scale than is usual in Strauss and a peculiarly spare ad spiky mood frequently prevails. -

Beata Kornatowska Wspomnienia Głosem Pisane : O Autobiografiach Śpiewaków

Beata Kornatowska Wspomnienia głosem pisane : o autobiografiach śpiewaków Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Litteraria Polonica 16, 140-154 2012 140 | FOLIA LITTERARIA POLONICA 2 (16) 2012 Beata Kornatowska Wspomnienia głosem pisane. O autobiografiach śpiewaków W literackim eseju Güntera de Bruyna poświęconym autobiografii czytamy: Opowiadający dokonuje pewnego okiełznania tego, co zamierza opowiedzieć, wtłacza to w formę, której wcześniej nie miało; decyduje o początku i zakończeniu, układa szczegóły [...] w wybranych przez siebie związkach, tak że nie są już tylko szczegółami, ale nabierają znaczenia, i określa punkty ciężkości1. Przy lekturze wspomnień znanych śpiewaków trudno oprzeć się wrażeniu, że przyszli na świat po to, żeby śpiewać. Już dobór wspomnień z dzieciństwa ma coś z myślenia magicznego: wydarzenia, sploty okoliczności, spotkania — wszystko to prowadzi do rozwoju kariery muzycznej. Dalsze powtarzalne elementy tych wspomnień to: odkrycie predyspozycji wokalnych i woli podję- cia zawodu śpiewaka, rola nauczycieli śpiewu i mentorów (najczęściej dyrygen- tów), największe sukcesy i zdobywanie kolejnych szczytów — scen kluczowych dla świata muzycznego, pamiętne wpadki, kryzysy wokalne, podszyte rywali- zacją relacje z kolegami, ciągłe podleganie ocenie publiczności, krytyków i dy- rygentów, myśli o konieczności zakończenia kariery, refleksje na temat doboru repertuaru, wykonawstwa i — generalnie — muzyki. W tle pojawiają się rów- nież wydarzenia z historii najnowszej, losy kraju i rodziny, kondycja instytucji muzycznych, uwarunkowania personalne. Te uogólnione na podstawie sporej liczby tekstów z niemieckiego kręgu ję- zykowego2 prawidłowości w organizowaniu wspomnień „głosem pisanych” chciałabym przedstawić na przykładzie wyróżniających się w mojej ocenie ja- kością autobiografii autorstwa ikon powojennej wokalistyki niemieckiej — Christy Ludwig ...und ich wäre so gern Primadonna gewesen. Erinnerungen („...a tak chciałam być primadonną. Wspomnienia”)3 i Dietricha Fischer-Dies- kaua Zeit eines Lebens. -

WAGNER and the VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’S Works Is More Closely Linked with Old Norse, and More Especially Old Icelandic, Culture

WAGNER AND THE VOLSUNGS None of Wagner’s works is more closely linked with Old Norse, and more especially Old Icelandic, culture. It would be carrying coals to Newcastle if I tried to go further into the significance of the incom- parable eddic poems. I will just mention that on my first visit to Iceland I was allowed to gaze on the actual manuscript, even to leaf through it . It is worth noting that Richard Wagner possessed in his library the same Icelandic–German dictionary that is still used today. His copy bears clear signs of use. This also bears witness to his search for the meaning and essence of the genuinely mythical, its very foundation. Wolfgang Wagner Introduction to the program of the production of the Ring in Reykjavik, 1994 Selma Gu›mundsdóttir, president of Richard-Wagner-Félagi› á Íslandi, pre- senting Wolfgang Wagner with a facsimile edition of the Codex Regius of the Poetic Edda on his eightieth birthday in Bayreuth, August 1999. Árni Björnsson Wagner and the Volsungs Icelandic Sources of Der Ring des Nibelungen Viking Society for Northern Research University College London 2003 © Árni Björnsson ISBN 978 0 903521 55 0 The cover illustration is of the eruption of Krafla, January 1981 (Photograph: Ómar Ragnarsson), and Wagner in 1871 (after an oil painting by Franz von Lenbach; cf. p. 51). Cover design by Augl‡singastofa Skaparans, Reykjavík. Printed by Short Run Press Limited, Exeter CONTENTS PREFACE ............................................................................................ 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 7 BRIEF BIOGRAPHY OF RICHARD WAGNER ............................ 17 CHRONOLOGY ............................................................................... 64 DEVELOPMENT OF GERMAN NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS ..68 ICELANDIC STUDIES IN GERMANY ......................................... -

(WA Opera Society

W.A.OPERA COMPANY (W.A. Opera Society - Forerunner) PR9290 Flyers and General 1. Faust – 14th to 23rd August; and La Boheme – 26th to 30th August. Flyer. 1969. 2. There’s a conspiracy brewing in Perth. It starts September 16th. ‘A Masked Ball’ Booklet. c1971. D 3. The bat comes to Perth on June 3. Don’t miss it. Flyer. 1971. 4. ‘The Gypsy Baron’ presented by The W.A. Opera Company – Gala Charity Premiere. Wednesday 10th May, 1972. Flyer. 5. 2 great love operas. Puccini’s ‘Madame Butterfly’ ; Rossini’s ‘The Barber of Seville’ on alternate nights. September 14-30. Flyer. 1972. D 6. ‘Rita’ by Donizetti and ‘Gallantry’ by Douglas Moore. Sept. 9th-11th, & 16th, 17th. 1p. flyer. c1976. 7. ‘Sour Angelica’ by Puccini, Invitation letter to workshop presentation. 1p..Undated. 8. Letter to members about Constitution Amendments. 2p. July 1976. 9. Notice of Extraordinary General Meeting re Constitution Change. 1p. 7 July 1976. 10. Notice of Extraordinay General Meeting – Agenda and Election Notice. 1p. July 1976. 11. Letter to Members summarising events occurring March – June 1976. 1p. July 1976. 12. Memo to Acting Interim Board of Directors re- Constitutional Developments and Confrontation Issues. 3p. July 1976. 13. Campaign letter for election of directors on to the Board. 3p. 1976. 14. Short Biographies on nominees for Board of Directors. 1p.. 1976. 15. Special Priviledge Offer. for ‘The Bear’ by William Walton and ‘William Derrincourt’ by Roger Smalley. 1p. 1977. 16. Membership Card. 1976. 17. Concession Vouchers for 1976 and 1977. 18. The Western Australian Opera Company 1980 Season. -

Contents: 1000 South Denver Avenue Suite 2104 Biography Tulsa, OK 74119 Critical Acclaim

Conductor Jack Price Managing Director 1 (310) 254-7149 Skype: pricerubin [email protected] Rebecca Petersen Executive Administrator 1 (916) 539-0266 Skype: rebeccajoylove [email protected] Olivia Stanford Marketing Operations Manager [email protected] Karrah O’Daniel-Cambry Opera and Marketing Manager [email protected] Mailing Address: Contents: 1000 South Denver Avenue Suite 2104 Biography Tulsa, OK 74119 Critical Acclaim Website: DIscography http://www.pricerubin.com Testimonials Indiana University Review Video LInks Complete artist information including video, audio and interviews are available at www.pricerubin.com Grzegorz Nowak – Biography Grzegorz Nowak is the Principal Associate Conductor of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in London. He has led the Orchestra on tours to Switzerland, Turkey and Armenia, as well as giving numerous concerts throughout the UK. His RPO recordings include Mendelssohn’s ‘Scottish’ and ‘Italian’ Symphonies, Shostakovich’s Symphony No.5, Dvořák’s Symphonies Nos. 6–9, all the symphonies of Schumann and complete symphonies and major orchestral works of Brahms and Tchaikovsky. He is also the Music Director & Conductor of the Orquesta Clásica Santa Cecilia and Orquesta Sinfonica de España in Madrid. Recordings of Grzegorz Nowak have been highly acclaimed by the press and public alike, winning many awards. Diapason in Paris praised his KOS live recording with Martha Argerich and Sinfonia Varsovia as ”indispensable…un must”, and its second edition won the Fryderyk Award. His recording of The Polish Symphonic Music of the XIX Century with Sinfonia Varsovia won the CD of the Year Award, the Bronze Bell Award in Singapore and Fryderyk Award nomination; the American Record Guide praised it as “uncommonly rewarding… 67 minutes of pure gold” and hailed his Gallo disc of Frank Martin with Biel Symphony as “by far the best”. -

DVORÁK of Eight Pieces for Piano Duet

GRZEGORZ NOWAK CONDUCTS DVO RÁK Symphonies no 6 - 9 Carnival Overture 3 CDs ˇ composer complied in 1878 with a set Symphony No.6 in D major, Op.60 the Vienna cancellation must have galled ANTONÍN DVORÁK of eight pieces for piano duet. These did the composer, was a resounding success. I. Allegro non tanto The work was published in Berlin in 1882 as (1841-1904) much to enhance his reputation abroad, II. Adagio and in 1884 he was invited to conduct ‘Symphony No.1’, ignoring the fact it actually III. Scherzo: Furiant-Presto had five symphonic predecessors, and leading his Stabat Mater in London, where his Antonín Dvorˇák was born in what was IV. Finale: Allegro con spirito to a situation where the celebrated work we music became immensely popular. In then known as Bohemia, in the small In the mid-1870s Dvorˇák, then in his now know as the Ninth appeared in print village of Mühlhausen, near Prague. 1891 he was made an honorary Doctor mid-thirties, was still struggling to gain as the Fifth. He was apprenticed as a butcher in of Music by Cambridge University and recognition and renown outside his native Dvorˇák’s earlier symphonies were strongly the following year made the first of his country. In 1874 he was awarded the first his father’s shop, encountering strong influenced by those of Beethoven. Indeed, visits to America, a country that would of several Austrian State Stipendium grants, paternal opposition to his intended his First Symphony, which was composed through which he made the acquaintance career as a musician. -

Wagner March 06.Indd

Wagner Society in NSW Inc. Newsletter No. 103, March 2006 IN NEW SOUTH WALES INC. President’s Report In Memoriam While on the subject of recordings, we are still waiting for the first opera of the promised set from the Neidhardt Birgit Nilsson, the Wagner Soprano Legend, Ring in Adelaide in 2004, and regretting that last year’s Dies at 87 and Tenor James King at 80 triumphal Tristan in Brisbane with Lisa Gasteen and John Birgit Nilsson, the Swedish soprano, died on 25 December Treleaven went unrecorded. 2005 at the age of 87 in Vastra Karup, the village where Functions she was born. Max Grubb has specially written for the Newsletter an extensive appraisal and appreciation of the On 19 February, we held our first function of 2006, at which voice, career and character of Nilsson (page 10). Nilsson’s Professor Kim Walker, Dean of the Sydney Conservatorium regular co-singer, Tenor James King has also died at eighty: of Music, spoke about the role of the Conservatorium, Florida, 20 November 2005 (see report page 14). the work of the Opera Studies Unit in particular, and the need to find private funding to replace government grants A LETTER TO MEMBERS which have been severely cut. Sharolyn Kimmorley then Dear Members conducted a voice coaching class with Catherine Bouchier, a voice student at the Con. From feedback received at and Welcome to this, our first Newsletter for 2006, in which since the function, members attending found this “master we mourn the passing of arguably the greatest Wagnerian class” a fascinating and rewarding window onto the work soprano of the second half of the 20th century, Birgit of the Conservatorium, and I’d like on your behalf to once Nilsson. -

Nietzsche, Debussy, and the Shadow of Wagner

NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tekla B. Babyak May 2014 ©2014 Tekla B. Babyak ii ABSTRACT NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER Tekla B. Babyak, Ph.D. Cornell University 2014 Debussy was an ardent nationalist who sought to purge all German (especially Wagnerian) stylistic features from his music. He claimed that he wanted his music to express his French identity. Much of his music, however, is saturated with markers of exoticism. My dissertation explores the relationship between his interest in musical exoticism and his anti-Wagnerian nationalism. I argue that he used exotic markers as a nationalistic reaction against Wagner. He perceived these markers as symbols of French identity. By the time that he started writing exotic music, in the 1890’s, exoticism was a deeply entrenched tradition in French musical culture. Many 19th-century French composers, including Felicien David, Bizet, Massenet, and Saint-Saëns, founded this tradition of musical exoticism and established a lexicon of exotic markers, such as modality, static harmonies, descending chromatic lines and pentatonicism. Through incorporating these markers into his musical style, Debussy gives his music a French nationalistic stamp. I argue that the German philosopher Nietzsche shaped Debussy’s nationalistic attitude toward musical exoticism. In 1888, Nietzsche asserted that Bizet’s musical exoticism was an effective antidote to Wagner. Nietzsche wrote that music should be “Mediterranized,” a dictum that became extremely famous in fin-de-siècle France. -

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

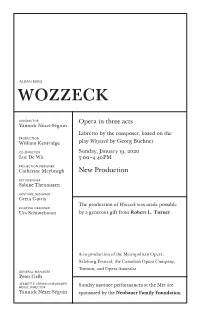

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J.