Travellers' Tales of Mingrelia and of the Ancient Fortress of Nokalakevi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Medieval Urban Economy in Wallachia

iANALELE ŞTIIN łIFICE ALE UNIVERSIT Ăł II „ALEXANDRU IOAN CUZA” DIN IA ŞI Tomul LVI Ştiin Ńe Economice 2009 ON THE MEDIEVAL URBAN ECONOMY IN WALLACHIA Lauren Ńiu R ĂDVAN * Abstract The present study focuses on the background of the medieval urban economy in Wallachia. Townspeople earned most of their income through trade. Acting as middlemen in the trade between the Levant and Central Europe, the merchants in Br ăila, Târgovi şte, Câmpulung, Bucure şti or Târg şor became involved in trading goods that were local or had been brought from beyond the Carpathians or the Black Sea. Raw materials were the goods of choice, and Wallachia had vast amounts of them: salt, cereals, livestock or animal products, skins, wax, honey; mostly imported were expensive cloth or finer goods, much sought after by the local rulers and boyars. An analysis of the documents indicates that crafts were only secondary, witness the many raw goods imported: fine cloth (brought specifically from Flanders), weapons, tools. Products gained by practicing various crafts were sold, covering the food and clothing demand for townspeople and the rural population. As was the case with Moldavia, Wallachia stood out by its vintage wine, most of it coming from vineyards neighbouring towns. The study also deals with the ethnicity of the merchants present on the Wallachia market. Tradesmen from local towns were joined by numerous Transylvanians (Bra şov, Sibiu), but also Balkans (Ragussa) or Poles (Lviv). The Transylvanian ones enjoyed some privileges, such as tax exemptions or reduced customs duties. Key words: regional history; medieval trade; charters of privilege; merchants; craftsmen; Wallachia JEL classification: N93 1. -

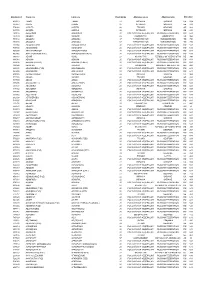

FÁK Állomáskódok

Állomáskód Orosz név Latin név Vasút kódja Államnév orosz Államnév latin Államkód 406513 1 МАЯ 1 MAIA 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 085827 ААКРЕ AAKRE 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 574066 ААПСТА AAPSTA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 085780 ААРДЛА AARDLA 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 269116 АБАБКОВО ABABKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 737139 АБАДАН ABADAN 29 УЗБЕКИСТАН UZBEKISTAN UZ 860 753112 АБАДАН-I ABADAN-I 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 753108 АБАДАН-II ABADAN-II 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 535004 АБАДЗЕХСКАЯ ABADZEHSKAIA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 795736 АБАЕВСКИЙ ABAEVSKII 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 864300 АБАГУР-ЛЕСНОЙ ABAGUR-LESNOI 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 865065 АБАГУРОВСКИЙ (РЗД) ABAGUROVSKII (RZD) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 699767 АБАИЛ ABAIL 27 КАЗАХСТАН REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN KZ 398 888004 АБАКАН ABAKAN 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 888108 АБАКАН (ПЕРЕВ.) ABAKAN (PEREV.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 398904 АБАКЛИЯ ABAKLIIA 23 МОЛДАВИЯ MOLDOVA, REPUBLIC OF MD 498 889401 АБАКУМОВКА (РЗД) ABAKUMOVKA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 882309 АБАЛАКОВО ABALAKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 408006 АБАМЕЛИКОВО ABAMELIKOVO 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 571706 АБАША ABASHA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 887500 АБАЗА ABAZA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 887406 АБАЗА (ЭКСП.) ABAZA (EKSP.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 -

Ethnobiology of Georgia

SHOTA TUSTAVELI ZAAL KIKVIDZE NATIONAL SCIENCE FUNDATION ILIA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS ETHNOBIOLOGY OF GEORGIA ISBN 978-9941-18-350-8 Tbilisi 2020 Ethnobiology of Georgia 2020 Zaal Kikvidze Preface My full-time dedication to ethnobiology started in 2012, since when it has never failed to fascinate me. Ethnobiology is a relatively young science with many blank areas still in its landscape, which is, perhaps, good motivation to write a synthetic text aimed at bridging the existing gaps. At this stage, however, an exhaustive representation of materials relevant to the ethnobiology of Georgia would be an insurmountable task for one author. My goal, rather, is to provide students and researchers with an introduction to my country’s ethnobiology. This book, therefore, is about the key traditions that have developed over a long history of interactions between humans and nature in Georgia, as documented by modern ethnobiologists. Acknowledgements: I am grateful to my colleagues – Rainer Bussmann, Narel Paniagua Zambrana, David Kikodze and Shalva Sikharulidze for the exciting and fruitful discussions about ethnobiology, and their encouragement for pushing forth this project. Rainer Bussmann read the early draft of this text and I am grateful for his valuable comments. Special thanks are due to Jana Ekhvaia, for her crucial contribution as project coordinator and I greatly appreciate the constant support from the staff and administration of Ilia State University. Finally, I am indebted to my fairy wordmother, Kate Hughes whose help was indispensable at the later stages of preparation of this manuscript. 2 Table of contents Preface.......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 1. A brief introduction to ethnobiology...................................................................................... -

12 Magin.Pdf

Chicago Open 2014: A Redoubtable Coupling of Editors Packet by Moose Drool. Cool, Cool, Cool. (Stephen Liu, Sriram Pendyala, Jonathan Magin, Ryan Westbrook) Edited by Austin Brownlow, Andrew Hart, Ike Jose, Gautam & Gaurav Kandlikar, and Jacob Reed Tossups 1. In the book with this number from Silius Italicus’s Punica, Hannibal and Varro rouse their troops to fight the Battle of Cannae. Juvenal’s satire of this number concerns Naevolus, a male prostitute upset because his patron won’t give him money. Neifile sings the song “Io mi son giovinetta” at the end of this day of The Decameron, which is the only day besides the first in which the stories follow no prescribed theme. The line “no day shall erase you from the memory of time” is taken from this numbered book of The Aeneid, in which Nisus and Euryalus massacre sleeping Rutuli soldiers. Dante kicks the head of Bocca degli Abati in this circle of Hell, which is divided into regions including Antenora and Ptolomea. In a Petrarchan sonnet, this numbered line begins after the “volta,” or “turn.” Antaeus lowers Dante and Virgil into this circle of Hell, where Dante encounters Count Ugolino eating the head of Ruggieri. For 10 points, name this circle of Hell in which traitors are frozen in a lake of ice, the lowest circle of Dante’s Inferno. ANSWER: nine [or ninth; or nove if you have an Italian speaker] 2. An essay by William Hazlitt praises a fictional member of this profession named “Madame Pasta.” In the 18th century, Aaron Hill wrote many works to instruct members of this profession, who were lampooned in Charles Churchill’s satire The Rosciad. -

Abstracta Iranica, Volume 30 | 2010 « the Perso-Ottoman Boundary and the Second Treaty of Erzurum in 1847 »

Abstracta Iranica Revue bibliographique pour le domaine irano-aryen Volume 30 | 2010 Comptes rendus des publications de 2007 « The Perso-Ottoman Boundary and the Second Treaty of Erzurum in 1847 ». The Journal of History, 90-1, 2007, pp. 62-91. [in Japanese] Akihiko Yamaguchi Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/abstractairanica/37797 DOI : 10.4000/abstractairanica.37797 ISSN : 1961-960X Éditeur : CNRS (UMR 7528 Mondes iraniens et indiens), Éditions de l’IFRI Édition imprimée Date de publication : 8 avril 2010 ISSN : 0240-8910 Référence électronique Akihiko Yamaguchi, « « The Perso-Ottoman Boundary and the Second Treaty of Erzurum in 1847 ». The Journal of History, 90-1, 2007, pp. 62-91. [in Japanese] », Abstracta Iranica [En ligne], Volume 30 | 2010, document 149, mis en ligne le 08 avril 2010, consulté le 27 septembre 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/abstractairanica/37797 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/abstractairanica. 37797 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 27 septembre 2020. Tous droits réservés « The Perso-Ottoman Boundary and the Second Treaty of Erzurum in 1847 ». The ... 1 « The Perso-Ottoman Boundary and the Second Treaty of Erzurum in 1847 ». The Journal of History, 90-1, 2007, pp. 62-91. [in Japanese] Akihiko Yamaguchi 1 This is not only a useful overview on the formation process of the Ottoman-Iran border, which eventually offered today’s Iran with its western frontiers with Turkey and Iraq, but also a good case study on the introduction of the modern Western frontier concept into Islamic Middle East states. Showing that the demarcation process in the region goes back to the Ottoman-Safavid conflicts, the author argues that the second Erzurum treaty (1847), which finally established the Ottoman-Qajar boundary, adhered fundamentally to the preceding treaties concluded between successive Iranian dynasties and the Ottomans. -

Review of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development Potentials in Georgia

FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular No. 1055/1 REU/C1055/1(En) ISSN 2070-6065 REVIEW OF FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT POTENTIALS IN GEORGIA Copies of FAO publications can be requested from: Sales and Marketing Group Office of Knowledge Exchange, Research and Extension Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations E-mail: [email protected] Fax: +39 06 57053360 Web site: www.fao.org/icatalog/inter-e.htm FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Circular No. 1055/1 REU/C1055/1 (En) REVIEW OF FISHERIES AND AQUACULTURE DEVELOPMENT POTENTIALS IN GEORGIA by Marina Khavtasi † Senior Specialist Department of Integrated Environmental Management and Biodiversity Ministry of the Environment Protection and Natural Resources Tbilisi, Georgia Marina Makarova Head of Division Water Resources Protection Ministry of the Environment Protection and Natural Resources Tbilisi, Georgia Irina Lomashvili Senior Specialist Department of Integrated Environmental Management and Biodiversity Ministry of the Environment Protection and Natural Resources Tbilisi, Georgia Archil Phartsvania National Consultant Thomas Moth-Poulsen Fishery Officer FAO Regional Office for Europe and Central Asia Budapest, Hungary András Woynarovich FAO Consultant FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS Rome, 2010 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

The Origin and Historical Background of Ottoman and Italian Velvets

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 2016 Velvet and Patronage: The Origin and Historical Background of Ottoman and Italian Velvets Sumiyo Okumura Dr. [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons Okumura, Sumiyo Dr., "Velvet and Patronage: The Origin and Historical Background of Ottoman and Italian Velvets" (2016). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. 1008. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/1008 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Velvet and Patronage: The Origin and Historical Background of Ottoman and Italian Velvets Dr. Sumiyo Okumura Velvets are one of the most luxurious textile materials and were frequently used in furnishings and costumes in the Middle East, Europe and Asia in the fifteenth to sixteenth centuries. Owing to many valuable studies on Ottoman and Italian velvets as well as Chinese and Byzantine velvets, we have learned the techniques and designs of velvet weaves, and how they were consumed. However, it is not well-known where and when velvets were started to be woven. The study will shed light on this question and focus on the origin, the historical background and development of velvet weaving, examining historical sources together with material evidence. -

Some Notes on the Topography of Eastern Pontos Euxeinos in Late Antiquity and Early

Andrei Vinogradov SOME NOTES ON THE TOPOGRAPHY OF EASTERN PONTOS EUXEINOS IN LATE ANTIQUITY AND EARLY BYZANTIUM BASIC RESEARCH PROGRAM WORKING PAPERS SERIES: HUMANITIES WP BRP 82/HUM/2014 This Working Paper is an output of a research project implemented within NRU HSE’s Annual Thematic Plan for Basic and Applied Research. Any opinions or claims contained in this Working Paper do not necessarily reflect the views of HSE. Andrei Vinogradov1 SOME NOTES ON THE TOPOGRAPHY OF EASTERN PONTOS EUXEINOS IN LATE ANTIQUITY AND EARLY BYZANTIUM2 This paper clarifies some issues of late antique and early Byzantine topography of Eastern Pontos Euxeinos. These questions can be divided into two large groups: the ecclesiastical topography and the locations of Byzantine fortresses. The earliest testimony of Apostolic preaching on the Eastern black sea coast—the list of the apostles by Pseudo- Epiphanius—following the ‘Chronicon’ of Hyppolitus of Rome, unsuccessfully connects South- Eastern Pontos Euxeinos to Sebastopolis the Great (modern Sukhumi), which subsequently gives rise to an itinerary of the apostle Andrew. The Early Byzantine Church in the region had a complicated arrangement: the Zekchians, Abasgians and possibly Apsilians had their own bishoprics (later archbishoprics); the Lazicans had a metropolitan in Phasis (and not in their capital Archaeopolis) with five bishop-suffragans. Byzantine fortresses, mentioned in 7th c sources, are located mostly in Apsilia and Missimiania, in the Kodori valley, which had strategic importance as a route from -

Droeba Extracts

From “Droeba” [Times] N.216 of 29 October 1883 Correspondence of “Droeba” ABKHAZIA, 10 October. ‘The Garden of Eden of which folk speak must have been right here — such an adorned land and tempered by nature you won’t be able to come across on the surface of the entire mother-earth!’ every viewer of Abkhazia will say as soon they set eyes on it, but, unfortunately, but what one won’t find here are Eden’s corresponding people. Abkhazia, as the name of the place itself shews us, belonged and belongs to the Abkhazians. It is true, the rolling out of time has on many an occasion ruined and on many an occasion ravaged this country, and incoming peoples have assigned their own names to the places here, but still the basic name for it no-one has been able to eliminate. Abkhazia is a country well known from ancient times. At the time of Jesus Christ’s coming upon the earth Simon the Canaanite apparently came to christianise Abkhazia — that’s the Simon at whose wedding Christ turned the water into wine. As soon as he arrived here, he was sentenced to death by King Aderk’i. This is what history tells us. On the spot where Simon suffered his punishment, following the spread of the christian faith, they raised a church in Simon’s name. Several years passed and the passage of time resulted in the reduction of christianity in Abkhazia and Simon’s church evidently fell into ruin. In this last period Russian monks requested of the authorities to renew this church and to create on this spot a monastery or wilderness. -

History 18Th-1917

Chapter 5. History: 18th Century-1917 Stanislav Lak’oba In the 80s of the 18th century the Abkhazian Keleshbey Chachba (Shervashidze, according to the Georgian variant of the family's surname) suddenly found himself in power as Abkhazia's sovereign prince. Over three decades he conducted an independent state-policy, successfully manœuvring between the interests of Turkey and Russia. The prince was distinguished for his intelligence, cunning and resolution, and his name was widely known beyond the frontiers of the Caucasus. Of tall stature, with sharp lines to the face and with flaming hair, he easily stood out from those around him and arrested the attention of his contemporaries -- military men, diplomats and travellers. Keleshbey speedily subordinated to himself the feudal aristocracy of Abkhazia, relying on the minor nobility and 'pure' peasants (Abkhaz anxa'j wy-tsk ja), each one of whom was armed with rifle, sabre and pistol. This permanent guard consisted of 500 warriors. Whenever war threatened, Keleshbey in no time at all would put out a 25,000-strong army, well armed with artillery, cavalry and even a naval flotilla. Upto 600 military galleys belonging to the ruler permanently cruised the length of the Black Sea coast from Batumi to Anapa -- the fortresses at Poti and Batumi were under the command of his nephews and kinsmen. During the first stage of his activities Keleshbey enjoyed the military and political backing of Turkey, under whose protectorate Abkhazia found itself. At the period when these relations were flourishing, the ruler built in Sukhum a 70-cannon ship and presented it to the sultan. -

CJSS Second Issue:CJSS Second Issue.Qxd

Caucasus Journal of Social Sciences The University of Georgia 2009 Caucasus Journal of Social Sciences UDC(uak)(479)(06) k-144 3 Caucasus Journal of Social Sciences Caucasus Journal of Social Sciences EDITOR IN CHIEF Julieta Andghuladze EDITORIAL BOARD Edward Raupp Batumi International University Giuli Alasania The University of Georgia Janette Davies Oxford University Ken Goff The University of Georgia Kornely Kakachia Associate Professor Michael Vickers The University of Oxford Manana Sanadze The University of Georgia Mariam Gvelesiani The University of Georgia Marina Meparishvili The University of Georgia Mark Carper The University of Alaska Anchorage Natia Kaladze The University of Georgia Oliver Reisner The Humboldt University Sergo Tsiramua The University of Georgia Tamar Lobjanidze The University of Georgia Tamaz Beradze The University of Georgia Timothy Blauvelt American Councils Tinatin Ghudushauri The University of Georgia Ulrica Söderlind Stockholm University Vakhtang Licheli The University of Georgia 4 Caucasus Journal of Social Sciences Printed at The University of Georgia Copyright © 2009 by the University of Georgia. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, in any form or any means, electornic, photocopinying, or otherwise, without prior written permission of The University of Georgia Press. No responsibility for the views expressed by authors in the Caucasus Journal of Social Sciences is assumed by the editors or the publisher. Caucasus Journal of Social Sciences is published annually by The University -

Imereti – in Between Georgian Centralism and Local Identity in Language

Journal of Ethnophilosophical Questions and Global Ethics – Vol. 1 (2), 2017 __________________________________________________________________________________ Imereti – In between Georgian centralism and local identity in language Timo Schmitz Imereti (or Imeretia) is a province in Georgia in the South Caucasus. It lies in the center of the country and has an important knot with its center – Kutaissi. Imeretians traditionally speak their own dialect of Georgian, however, in a certain aspect, Imeretian serves the cause of a language. As such, it is an important part of the Imeretian heritage and identity. Imereti had its own kingdom which existed form the 13th till the 19th century and was sometimes part of Georgia, Russia and the Ottomans, and therefore had a lot of different influences shaping their identity. Even further, the region had a supralocal importance, as the princedoms of Abkhazia, Mingrelia and Guria were part of Imereti from time to time and therefore, the region had an important impact on whole Georgia and its history. The importance of the different kingdoms is necessary in understanding the different identities within Georgia. The Meskheti Kingdom covered the western part of Georgia and is known today for the Meskhetian Turks. It is the gate between Christianity and Islam. The Kartli kingdom is name giving for the Georgian language – Kartuli. The author of this paper informally questioned people from Georgia about their views on the Imeretian language and its perspective and therefore all the accounts given here are first-hand accounts. Imeretian is quite understandable for people all over Georgia and has a rather dialectal character. As such, Georgians see Imereti dialect downgraded and for many it does not sound educated.