The Rhetoric of Malcolm X's Legacy: by Any (Available)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X Talk It out 17

Writing for Understanding ACTIVITY Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X Talk It Out 17 Overview Materials This Writing for Understanding activity allows students to learn about and write • Transparency 17A a fictional dialogue reflecting the differing viewpoints of Martin Luther King Jr. • Student Handouts and Malcolm X on the methods African Americans should use to achieve equal 17 A –17C rights. Students study written information about either Martin Luther King Jr. • Information Master or Malcolm X and then compare the backgrounds and views of the two men. 17A Students then use what they have learned to assume the roles of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X and debate methods for achieving African American equality. Afterward, students write a dialogue between the two men to reveal their differing viewpoints. Procedures at a Glance • Before class, decide how you will divide students into mixed-ability pairs. Use the diagram at right to determine where they should sit. • In class, tell students that they will write a dialogue reflecting the differing viewpoints of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X on the methods African Americans should use to achieve equal rights. • Divide the class into two groups—one representing each man. Explain that pairs will become “experts” on either Martin Luther King Jr. or Malcolm X. Direct students to move into their correct places. • Give pairs a copy of the appropriate Student Handout 17A. Have them read the information and discuss the “stop and discuss” questions. • Next, place each pair from the King group with a pair from the Malcolm X group. -

By Any Means Necessary

MALCOLM X BY ANY MEANS NECESSARY A Biography by WALTER DEAN MYERS NEW YORK Xiii Excerpts from The Autobiography of Malcolm X, by Malcolm X, with the assistance of Alex Haley. Copyright © 1964 by Alex Haley and Malcolm X. Copyright © 1965 by Alex Haley and Betty Shabazz. Reprinted by permission of Random House Inc. Excerpts from Malcolm X Speaks, copyright © 1965 by Betty Shabazz and Pathfinder Press. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission of Pathfinder Press. “Great Bateleur” is used by permission of Wopashitwe Mondo Eyen we Langa. If you purchased this book without a cover, you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher, and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.” Copyright © 1993 by Walter Dean Myers All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Focus, a division of Scholastic Inc., Publishers since 1920. SCHOLASTIC, SCHOLASTIC FOCUS, and associated logos are trademarks and/ or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third- party websites or their content. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. ISBN 978-1- 338- 30985-0 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 20 21 22 23 24 Printed in the U.S.A. -

X-Men Allegory Allusion Essay

Pull 1 Pull 2 Sam Pull are hated, feared, and despised collectively by humanity for no other reason than that they are Ms. Ekrofergustitz mutants. So what we have..., intended or not, is a book that is about racism, bigotry, and Language Arts 8 prejudice." In the comics, the X-men and others like them, were often victims of mob violence 31 January 2017 perpetrated by the hate group, “Friends of Humanity.” This is similar to the violence carried out Art Imitating Life against minorities by the Ku Klux Klan. There is no doubt that both groups struggled against “Your humans slaughter each other because of the color of your skin, or your faith or hateful humans. your politics, or for no reason at all. Too many of you hate as easily as you draw breath” Equally important are the characters and people involved. The leader and founder of the -Magneto (Stan Lee). Even though this quote comes from a fictional universe, it can still apply X-Men is Professor Charles Xavier, a telepath who believes in nonviolence. His character is to our world. Stan Lee, the creator of comics like Spiderman and The Avengers , invented an very similar to Martin Luther King, Jr. Xavier’s students even referred to their missions as allegory about discrimination with The X-Men . This comic series was published in 1963 when “Xavier’s Dream,” possibly referencing MLK’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Moreover, Xavier’s the United States was in the middle of the Civil Rights Movement. It is difficult to ignore the antagonist Magneto, who can control magnetic fields and uses a different approach to dealing similarities between the conflicts the X-men experienced and the discrimination endured by with hateful humans, is comparable to the militant civil rights leader, Malcolm X. -

The Contemporary Rhetoric About Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X in the Post-Reagan Era

ABSTRACT THE CONTEMPORARY RHETORIC ABOUT MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., AND MALCOLM X IN THE POST-REAGAN ERA by Cedric Dewayne Burrows This thesis explores the rhetoric about Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X in the late 1980s and early 1990s, specifically looking at how King is transformed into a messiah figure while Malcolm X is transformed into a figure suitable for the hip-hop generation. Among the works included in this analysis are the young adult biographies Martin Luther King: Civil Rights Leader and Malcolm X: Militant Black Leader, Episode 4 of Eyes on the Prize II: America at the Racial Crossroads, and Spike Lee’s 1992 film Malcolm X. THE CONTEMPORARY RHETORIC ABOUT MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., AND MALCOLM X IN THE POST-REAGAN ERA A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English by Cedric Dewayne Burrows Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2005 Advisor_____________________ Morris Young Reader_____________________ Cynthia Leweicki-Wison Reader_____________________ Cheryl L. Johnson © Cedric D. Burrows 2005 Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One A Dead Man’s Dream: Martin Luther King’s Representation as a 10 Messiah and Prophet Figure in the Black American’s of Achievement Series and Eyes on the Prize II: America at the Racial Crossroads Chapter Two Do the Right Thing by Any Means Necessary: The Revival of Malcolm X 24 in the Reagan-Bush Era Conclusion 39 iii THE CONTEMPORARY RHETORIC ABOUT MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR., AND MALCOLM X IN THE POST-REAGAN ERA Introduction “What was Martin Luther King known for?” asked Mrs. -

S/E(F% /02 R/E',A F- B/Uez

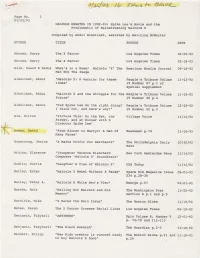

-: s/e(f% /02 r/e',A f- B/uez- Page No. 03/24/93 MALCOLMDEBATES IN 1992-93: Spike Lee's Movie and the Problematic of Mainstreaming Malcolm X Compiled by Abdul Alkalimat, aesisted by Mei-Ling McWorter AUTHOR TITLE SOURCE DATE Abrams, Garry The X Factor Los Angeles Times 02-06-92 Abrams, Garry The X Factor Los Angeles Times O2-L8-92 AIim, Dawud R Abdul What's in a Name? Malcolm "X" The American Muslim Journal 09-18-92 Man Not The Image Alkalimat, Abdul "Malcolm X: A warrior for these People's Tribune Volume tt-23-92 tlmeE" 19 Number 47 p.1 of special supplement Alkalimat, Abdul "Malcolm X and the struggle for the People's Tribune Volume Ll-16-92 future" 19 Number 46 p.4 AIkaIimat, Abdul "Did spike Lee do the right thing? People's Tribune Volume 12-28-92 I think not, and here's whyl" 19 Number 52 p.3 AIs, Hilton "Picture This: On the Set, the vilLage Voice tt/tolg2 Street, and at Dinner with X \*L-- Director Spike Lee" Ansen, David "From Sinner to Martyr: A Man Of Newsweek p.74 Lt-t5-92 4\ Many Faces" Armstrong, Jenice "X Marks Profit for Merchants" The Philadelphia Daily LO/30/92 News Atkins, Clarence "Trumpeter Terence Blanchard New York Amsterdam News l-L/14/92 Composes 'Malcolm X, Soundtrack" Austin, Curtis "Daughter's View of Malcolm X" USA Today tt / t6/e2 BaiIey, Ester "MaIcoIm X Rebel Without A pause" Spare Rib Magazine fssue 05-01-92 234 p.28-36 Bailey, Peter A. -

B.E.S.T. Academy Middle School 2014-2015 Summer Reading Books, Projects, and Rubric

B.E.S.T. Academy Middle School 2014-2015 Summer Reading Books, Projects, and Rubric 6th Grade Trapped Between the Lash and the Gun by Arvella Whitmore (630L) Jordan is going to join a gang. But just as he's about to start his future with the Cobras, his past calls him back. Way back -- to the nineteenth-century, where he meets his ancestors and gets a bitter taste of what life was like for them as slaves. Jordan must live with the constant threat of the whip's lash. His journey back in time will strike a chord with any young person who has felt trapped by hard times and difficult choices. (http://www.scholastic.com/teachers/book/trapped-between-lash-and-gun#cart/cleanup) Middle School: The Worst Years of My Life by Chris Tebbetts and James Patterson (700L) Rafe Khatchadorian has enough problems at home without throwing his first year of middle school into the mix. Lucky for Rafe, he's got a foolproof plan for the best year ever, if only he can pull it off. With his best friend Leonardo the Silent awarding the points, Rafe tries to break every rule in his school's oppressive Code of Conduct. Chewing gum in class is worth 5,000 points. Running in the hallway is 10,000. Pulling the fire alarm, 50,000! But when Rafe's game starts to catch up with him, he'll have to decide if winning is all that matters, or if he's finally ready to face the truths he's been avoiding. -

Violence Prevention: Reconsidering Malcolm X

TEACHING TOLERANCE UPPER GRADES ACTIVITY WWW.TEACHINGTOLERANCE.ORG K 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Violence Prevention: Reconsidering Malcolm X HANDOUT I: RETHINKING MALCOLM X When most people think of Malcolm X, a few phrases come immediately to mind: by any means necessary; blue- eyed devils; militant black leader. One of the dominant images of Malcolm X in the popular imagination depicts him standing beside a window, rifle in hand. The media portrayed him as an angry and violent man, an advocate of race war, although a textual analysis (http://www.walterlippmann.com/mx-nyt.html ) of his statements on violence suggests that, particularly in the later years of his life, he advocated only self-defense. Born in 1925 as Malcolm Little in Omaha, Neb., Malcolm X endured many transformations during his short life. The Autobiography of Malcolm X begins with a rather salacious description of Malcolm’s fast lifestyle as a zoot-suiter (http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/zoot/eng_sfeature/sf_zoot_mx.html). The structure ofAutobiography devotes the first 10 chapters to Malcolm’s criminal persona — what he later referred to and condemned as a “glamour image” of the hustler. He believed the hustler image endangered impressionable youth because it glorified vice, so he wanted people to know how treacherous and depressing a hustler’s life really is. At the age of 21, after hustling in New York, Boston and Detroit, Malcolm was sentenced to eight to 10 years in prison for armed robbery. While incarcerated, he read dictionaries and encyclopedias and became a member of the Nation of Islam, which encouraged him to lead a clean, drug-free and chaste lifestyle. -

Ditated Invasions of Angola, Mozambique, Zambia, Lesotho

AFRICAN STATES AND THE SOUTH AFRICA PROBLEM Boniface I . Obichere The prob 1em of apartheid in South Africa is an African lem. It fs a problem that is basic to the existence of many independent states of contemporary Africa. Africans find themselves in positions of political, religious, omic, social, cultural and military leadership owe it to er Africa and humanity to face the problem of Apartheid in h Africa as a most urgent problem ca 11 ing for immediate tion from within. The co-operation and collaboration of nations and peoples of Europe, Asia, the Americas and ra 1asia can be sought and shou 1d be engendered in the ecution of military and diplomatic tactics and strategies the elimination of aPartheid in South Africa. Recently, positive action was taken by the African states are members of the British Commonwealth of Nations by r effective boycott of the Commonwealth Games in Edinburgh 11 as the associated Commonwealth Art Festival which d in Edinburgh on July 17, 1986. The remorseless and 1 massacre of unanned Africans in South Africa, the ditated invasions of Angola, Mozambique, Zambia, Lesotho other independent African states by South African forces impunity, the obdurate relentlessness of the Pretoria and their many other international and domestic crimes more than enough justification for concerted Africa iation •by any means necessary," according to Malcolm X. castigation of the white minority rulers of South Africa r. Kwame Nkrumah on April 7, 1960 during the Positive t n Conference For Peace and Security in Africa held in c still holds true. He stated: •tt is ironical to think the rulers of South Africa call themselves Christians. -

By ANY MEANS NECESSARY: USING VIOLENCE and SUBVERSION to CHANGE UNJUST LAW

By ANY MEANS NECESSARY: USING VIOLENCE AND SUBVERSION TO CHANGE UNJUST LAW Paul Butler* There remains law in the United States that discriminates against African Americans. Important legal advancements in racial justice in the United States historically have been accomplished by tactics that included subversion and vio- lence. This Article evaluates the use of subversion and violence to change con- temporary law perceived as discriminatory, when traditional methods are ineffective or too slow. It applies just war theory to determine whether radical tactics are morally justified to defeat certain U.S. criminal laws. This Article recommends an application of the doctrine of just war for nongovernmental actors. In light of considerable evidence that the death penalty and federal co- caine sentencing laws discriminate against African Americans, subversion-in- cluding lying by prospective jurors to get on juries in death penalty and cocaine cases-is morally justified. Limited violence is also morally justified, under just war theory, to end race-based executions. Those concerned about morality should not, however, use "any means necessary" to defeat race discrimination. Minorities must tolerate some discrimination, even if they know they have the power to end it. INTRODUCTION: CRITICAL QUESTIONS ABOUT CRIT TACTICS ................... 723 I. CHANGING THE LAW: THE OLD WAYS .................................... 725 I1. Two CONTEMPORARY EXAMPLES OF DISCRIMINATORY LAWS .............. 728 A . C apital Punishm ent ............................................... 730 B. C rack C ocaine ................................................... 733 Ii. THE NEW WAYS: CRIT JURORS AND RACE REBELS ........................ 737 A . C ritical T actics ................................................... 737 B. Subversion ....................................................... 738 1. Lying to Save Lives ........................................... 738 a. Case 1: Death Penalty ..................................... 740 b. Case 2: Crack Cocaine ................................... -

From Malcolm Little to Malcolm X to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz-Al-Sabann to Omowale: 7 Degrees of Separation

From Malcolm Little to Malcolm X to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz-Al-Sabann to Omowale: 7 Degrees of Separation ______________________________________________________________________________ Baba Keita Sipho Thompson Clark Atlanta University Abstract The truths of our beloved ancestor, Malcolm X, are of extraordinary worth and value to black and African people throughout the world—the people whom he loved. Not only are these truths available from which to gain wisdom, but these truths can have significant impact on the lives and experiences of those black and African people who choose to listen and believe them. Introduction …Whoever steals a man and sells him, and anyone found in possession of him, shall be put to death. (Holy Bible ESV, 21:15-17) Understanding that the work of Malcolm was unfinished, leaving a restless world filled with unsettled claims; it is critical that black and African people throughout the world seek the truths of the Egun (ancestors).1 In laying a foundation for the particular research that speaks from Malcolm to his 7 Degrees of Separation, the truths from the Egun will reveal solutions that can be interpreted and considered in implementation of relief of black and African people from oppression in all of its forms, all over the world. In most scholarly research, studies often are categorized with each category focusing on a particular component of the major theory being investigated. In this present work, as categorization is integral to colonization, the valuable information being communicated refuses to be filtered or distilled as Malcolm X was known for making it plain. However, the work of Malcolm is organic. -

Reader's Guide for X: a Novel

READER’S GUIDE 2017 – 2018 Presented by MICHIGAN HUMANITIES COUNCIL GREAT MICHIGAN READ X: A Novel Ilyasah Shabazz with Kekla Magoon GREAT MICHIGAN READ READER’S GUIDE | 3 WHAT IS THE GREAT MICHIGAN READ? Great Michigan Read: One title, one state, and thousands engaged in literary discussion WHAT IS THE GREAT MICHIGAN READ? The Michigan Humanities Council’s Great Michigan Read is a book club for the entire state with a focus on a single book – X: A Novel by Ilyasah Shabazz and Kekla Magoon. The program is intended for young adults to senior citizens with broad goals of making literature more accessible and appealing while also encouraging residents to learn more about our state and individual identities. CONTENTS WHY X: A NOVEL? HOW CAN I PARTICIPATE? 2-3 WHAT IS THE GREAT MICHIGAN READ? No life is set in stone. Malcolm was a Pick up a copy of X: A Novel and young man with boundless potential supporting materials at your local 4-5 X: A NOVEL AND AUTHOR but with the odds stacked against library, your favorite bookstore, or ILYASAH SHABAZZ him. Losing his father under suspicious download the e-book. Read the book, 6-7 X: A NOVEL AND AUTHOR circumstances and his mother to a share and discuss it with your friends, KEKLA MAGOON mental health hospital, Malcolm fell and participate in Great Michigan Read into a life of petty crime and eventually events in your community and online. 8-9 AUTHOR’S NOTE: ILYASAH SHABAZZ prison. Instead of letting prison be his Register your library, school, company, 10-11 CHRONOLOGY OF MALCOLM IN MICHIGAN downfall, Malcom found a religion, or book club and receive copies of a voice, and the podium that would 12-13 MALCOLM’S LANSING reader’s guides, teacher’s guides, GET CONNECTED & FOLLOW US! eventually make him one of the most Join the Michigan Humanities bookmarks, and other informational 14-15 A FAMILY OF ACTIVISTS prominent figures in the burgeoning Council Facebook group, or follow materials at no cost. -

Malcolm X's Critique of the Education of Black People Morris, Jerome Ewestern Journal of Black Studies 07-01-2001

6/2/2014 Document Page: Malcolm X's critique of the education of Black people Malcolm X's critique of the education of Black people Morris, Jerome EWestern Journal of Black Studies 07-01-2001 Malcolm X's critique of the education of Black people Byline: Morris, Jerome E Volume: 25 Number: 2 ISSN: 01974327 Publication Date: 07-01-2001 Page: 126 Type: Periodical Language: English Abstract HEADNOTE Noticeably absent from discussions of Malcolm Xs contribution to the modern Black freedom movement is his critique of the education of Black people in the United States. Too often, critiques of the Black experience are given more validity if emanating from formally trained academics. In this article, the author illustrates how Malcolm X used his life experiences as the basis for his critique of the education of Black people. Explicated is Malcolm's incisive critique of major educational issues facing Black people during the height of his leadership in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Throughout, the author illuminates the importance of situating Malcolm X within the historical tradition of Black intellectual activism, and concludes by highlighting the legacy of Malcolm's revolutionary spirit in contemporary African American education. IMAGE PHOTOGRAPH Introduction This article focuses on Malcolm X's critique of the education of people of African descent in the United States from the time of his leadership within the Nation of Islam, until his assassination in 1965. To place Malcolm X in the center of a discussion on Black education, on the surface, might appear as another effort to appropriate his life for mere intellectual analysis.