T Rediscovering Malcolm's Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

João Pedro Valladão Pinheiro Improving the Quality of the User

João Pedro Valladão Pinheiro Improving the Quality of the User Experience by Query Answer Modification Dissertação de Mestrado Dissertation presented to the Programa de Pós–graduação em Informática of PUC-Rio in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Mestre em Informática. Advisor : Prof. Marco Antonio Casanova Co-advisor: Profa. Elisa Souza Menendez Rio de Janeiro April 2021 João Pedro Valladão Pinheiro Improving the Quality of the User Experience by Query Answer Modification Dissertation presented to the Programa de Pós–graduação em Informática of PUC-Rio in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Mestre em Informática. Approved by the Examination Committee: Prof. Marco Antonio Casanova Advisor Departamento de Informática – PUC-Rio Profa. Elisa Souza Menendez Co-Advisor Campus Xique-Xique – Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia Baiano Prof. Antonio Luz Furtado Departamento de Informática – PUC-Rio Prof. Luiz André Portes Paes Leme Departamento de Ciências da Computação – UFF Rio de Janeiro, April 30th, 2021 All rights reserved. João Pedro Valladão Pinheiro João Pedro Valladão Pinheiro holds a bachelor degree in Computer Engineering from Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio). His main research topics are Semantic Web and Information Retrieval. Bibliographic data Pinheiro, João Pedro V. Improving the Quality of the User Experience by Query Answer Modification / João Pedro Valladão Pinheiro; advisor: Marco Antonio Casanova; co-advisor: Elisa Souza Menendez. – 2021. 55 f: il. color. ; 30 cm Dissertação (mestrado) - Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Departamento de Informática, 2021. Inclui bibliografia 1. Computer Science – Teses. 2. Informatics – Teses. 3. Pergunta e Resposta (QA). -

Newyork 08-1

Representative Hakeem Jeffries 117th United States Congress New York's 8TH Congressional District NUMBER OF DELIVERY SITES IN 37 CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT (main organization in bold) BEDFORD STUYVESANT FAMILY HEALTH CENTER, INC., THE Broadway Family Health Center - 1238 Broadway Brooklyn, NY 11221-2906 PS 256 - School Based Hlth Ctr - 114 Kosciuszko St Brooklyn, NY 11216-1007 PS 309 - School Based Hlth Ctr - 794 Monroe St Brooklyn, NY 11221-3501 PS 54 - School Based Hlth Ctr - 195 Sandford St Brooklyn, NY 11205-4525 BETANCES HEALTH CENTER Betances Health Center at Bushwick - 1427 Broadway Brooklyn, NY 11221-4202 BROOKLYN PLAZA MEDICAL CENTER Benjamin Banneker Academy Sbh - 77 Clinton Ave Brooklyn, NY 11205-2302 Whitman, Ingersoll, Farragut H C - 297 Myrtle Ave Brooklyn, NY 11205-2901 BROWNSVILLE COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION BMS Dental@Genesis - 330 Hinsdale St Brooklyn, NY 11207-4518 BMS@Ashford - 650 Ashford St Brooklyn, NY 11207-7315 BMS@Genesis - 360 Snediker Ave Brooklyn, NY 11207-4552 BMS@Jefferson High School Campus - 400 Pennsylvania Ave Brooklyn, NY 11207-4707 CARE FOR THE HOMELESS Bushwick Family Residence - 1675 Broadway Brooklyn, NY 11207-1495 Care Found Here: Junius St - 91 Junius St Brooklyn, NY 11212-8021 St. John's Bread and Life - 795 Lexington Ave Brooklyn, NY 11221-2903 COMMUNITY HEALTHCARE NETWORK, INC. Dr Betty Shabazz Health Center - 999 Blake Ave Brooklyn, NY 11208-3535 Medical Mobile Van (3) - 999 Blake Ave Brooklyn, NY 11208-3535 Medical Mobile Van (4) - 999 Blake Ave Brooklyn, NY 11208-3535 FLOATING HOSPITAL INCORPORATED (THE) Auburn Assessment Center - 39 Auburn Pl Brooklyn, NY 11205-1946 Flatlands - 10875 Avenue D Brooklyn, NY 11236-1931 Help I Family Center - 515 Blake Ave Brooklyn, NY 11207-4502 HOUSING WORKS HEALTH SERVICES III, INC. -

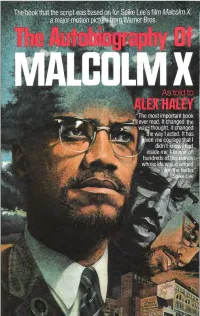

The-Autobiography-Of-Malcolm-X.Pdf

The absorbing personal story of the most dynamic leader of the Black Revolution. It is a testament of great emotional power from which every American can learn much. But, above all, this book shows the Malcolm X that very few people knew, the man behind the stereotyped image of the hate-preacher-a sensitive, proud, highly intelligent man whose plan to move into the mainstream of the Black Revolution was cut short by a hail of assassins' bullets, a man who felt certain "he would not live long enough to see this book appear. "In the agony of [his] self-creation [is] the agony of an entire.people in their search for identity. No man has better expressed his people's trapped anguish." -The New York Review of Books Books published by The Ballantine Publishing Group are available at quantity discounts on bulk purchases for premium, educational, fund-raising, and special sales use. For details, please call 1-800-733-3000. THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OFMALCOLMX With the assistance ofAlex Haley Foreword by Attallah Shabazz Introduction by M. S. Handler Epilogue by Alex Haley Afterword by Ossie Davis BALLANTINE BOOKS• NEW YORK Sale of this book without a front cover may be unauthorized. If this book is coverless, it may have been reported to the publisher as "unsold or destroyed" and neither the author nor the publisher may have received payment for it. A Ballantine Book Published by The Ballantine Publishing Group Copyright© 1964 by Alex Haley and Malcolm X Copyright© 1965 by Alex Haley and Betty Shabazz Introduction copyright© 1965 by M. -

124-130 WEST 125TH STREET up to Between Adam Clayton Powell Jr and Malcolm X Blvds/Lenox Avenue 22,600 SF HARLEM Available for Lease NEW YORK | NY

STREET RETAIL/RESTAURANT/QSR/MEDICAL/FITNESS/COMMUNITY FACILITY 3,000 SF 124-130 WEST 125TH STREET Up To Between Adam Clayton Powell Jr and Malcolm X Blvds/Lenox Avenue 22,600 SF HARLEM Available for Lease NEW YORK | NY ARTIST’S RENDERING 201'-10" 2'-0" 1'-4" 19'-5" 1'-5" 3" SLAB 2'-4" 21'-0" 8" 16'-1" 15'-6" 39'-9" 4'-9" 46'-0" 5'-5" DISPLAY CLG 1'-3" 5'-8" 40'-5" OFFICE 12'-0" 47'-7" B.B. 7'-1" 72'-6" 13'-2" D2 4'-4" 4'-0" 10'-2" 74'-2" 11'-4" 42'-3" 11'-2" 4'-9" 8'-4" 1'-3" 17'-6" 11" 2'-4" 138'-11" 5'-11" 1'-11" 7'-1" 147'-1" GROUND FLOOR GROUND 34'-9" 35'-1" 1'-4" 34'-8" 2x4 33'-10" 2x4 CLG. PARAMOUNT CLG. 12'-3" 124 W. 125 ST 11'-10" 24'-6" 23'-6" DISPLAY CTR 22'-11" D.H. 10'-10" 16'-0" 8'-11" 1'-4" 2'-5" 4'-2" GAS MTR EP EP ELEC 1'-5" 2'-10" 4" 7" 1'-4" 6" 1'-6" 11" 7'-0" 52'-0" 12'-11" 1'-2" CLG. 1'-10"1'-0" 3'-2" D2 10'-3" 36'-10" UP7" DN 11" 4'-8" 2x4 2'-3" 5'-3" DISPLAY CTR 13'-8" 6'-3" 7'-0" CLG. 7'-0" 7'-3" 7'-11" UP 11" 11'-8" 9'-10" 9'-10" AJS GOLD & DIAMONDS 2'-9" 6" 2x4 4" 7'-4" 126 W. 125 ST 2'-4" 2'-8" 2'-4" CLG. -

The BG News February 20, 2001

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 2-20-2001 The BG News February 20, 2001 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News February 20, 2001" (2001). BG News (Student Newspaper). 6766. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/6766 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. State University TUESDAY February 20, 2001 BASKETBALL: CLOUDY Men's Basketball faces HIGH43ILOW34 top ranked Kent today at www.binews.com 8 p.m.; PAGE 10 independent student press VOLUME 90 ISSUE 101 Student groups'budgets probed ByCrarfUford ed among 60-70 organizations. The SOFB had proposed to put money for transportation, where CHIEF REPORTER Last year the total amount of caps on things such as how another organization doesn't," CAMPUS ORGANIZATIONS REQUEST FUNDS Every year at this time, each of money that was applied for was much an organization could he said. "One group may need University campus organizations make their requests to the Student the University's campus organi- $400,000. This year it is $350,000. receive toward T-shirts or other more money for conferences Organization Funding board for their programs. zations make their pitch to the In an attempt to curb the promotional items. -

Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X Talk It out 17

Writing for Understanding ACTIVITY Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X Talk It Out 17 Overview Materials This Writing for Understanding activity allows students to learn about and write • Transparency 17A a fictional dialogue reflecting the differing viewpoints of Martin Luther King Jr. • Student Handouts and Malcolm X on the methods African Americans should use to achieve equal 17 A –17C rights. Students study written information about either Martin Luther King Jr. • Information Master or Malcolm X and then compare the backgrounds and views of the two men. 17A Students then use what they have learned to assume the roles of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X and debate methods for achieving African American equality. Afterward, students write a dialogue between the two men to reveal their differing viewpoints. Procedures at a Glance • Before class, decide how you will divide students into mixed-ability pairs. Use the diagram at right to determine where they should sit. • In class, tell students that they will write a dialogue reflecting the differing viewpoints of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X on the methods African Americans should use to achieve equal rights. • Divide the class into two groups—one representing each man. Explain that pairs will become “experts” on either Martin Luther King Jr. or Malcolm X. Direct students to move into their correct places. • Give pairs a copy of the appropriate Student Handout 17A. Have them read the information and discuss the “stop and discuss” questions. • Next, place each pair from the King group with a pair from the Malcolm X group. -

Tone Parallels in Music for Film: the Compositional Works of Terence Blanchard in the Diegetic Universe and a New Work for Studio Orchestra By

TONE PARALLELS IN MUSIC FOR FILM: THE COMPOSITIONAL WORKS OF TERENCE BLANCHARD IN THE DIEGETIC UNIVERSE AND A NEW WORK FOR STUDIO ORCHESTRA BY BRIAN HORTON Johnathan B. Horton B.A., B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Richard DeRosa, Major Professor Eugene Corporon, Committee Member John Murphy, Committee Member and Chair of the Division of Jazz Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Horton, Johnathan B. Tone Parallels in Music for Film: The Compositional Works of Terence Blanchard in the Diegetic Universe and a New Work for Studio Orchestra by Brian Horton. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2017, 46 pp., 1 figure, 24 musical examples, bibliography, 49 titles. This research investigates the culturally programmatic symbolism of jazz music in film. I explore this concept through critical analysis of composer Terence Blanchard's original score for Malcolm X directed by Spike Lee (1992). I view Blanchard's music as representing a non- diegetic tone parallel that musically narrates several authentic characteristics of African- American life, culture, and the human condition as depicted in Lee's film. Blanchard's score embodies a broad spectrum of musical influences that reshape Hollywood's historically limited, and often misappropiated perceptions of jazz music within African-American culture. By combining stylistic traits of jazz and classical idioms, Blanchard reinvents the sonic soundscape in which musical expression and the black experience are represented on the big screen. -

Teacher Resource Guide

uide Teacher Resource G : Before the Show About the Performance About the Artist About the Directorial Consultant Coming to the Theater Pre-Show Activities Huffington Post Review Compare and Contrast Respond in Writing The Civil Rights Movement Peace and Brotherhood The lessons and activities in this guide are driven by the Into the Words – Theater Vocabulary Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Post-Show Activities Subjects (2010) which help ensure that all students are Rhapsody in Black Content Vocabulary college and career ready in literacy no later than the end Comfortable vs. Challenging Conversations of high school. The College and Career Readiness (CCR) I, Too, Sing America Standards in Reading, Writing, Speaking and Listening, Huffington Post RE-View and Language define general, cross-disciplinary literacy Perspective in Poetry expectations that must be met for students to be prepared Cloze & Context Clues to enter college and workforce training programs ready to Dive Deeper succeed. Recommended Download Works Cited 21st century skills of creativity, critical thinking and collaboration are embedded in process of bringing the page to the stage. Seeing live theater encourages students to This guide contains pre-show/post-show classroom read, develop critical and creative thinking and to be curious activities that include specific student learning targets about the world around them. to use in their existing curriculum. The classroom activities are purposefully open ended and educators/ This Teacher Resource Guide includes background youth service professionals are encouraged to make information, questions, and activities that can stand alone appropriate adaptations to specific learning targets or work as building blocks toward the creation of a complete in order to meet the individualized needs of their unit of classroom work. -

Invisible Man on the Road

Summer Reading for Incoming 11th Graders Response Essay (50 points) Group Presentation (50 points) Step 1: Choose and obtain one book from the list below to read over the summer before your junior year. Step 2: Read your chosen book and write a response essay to the book of at least 2-3 pages (anything less than 2 FULL pages will lose points). Your response should discuss your thoughts, responses, and reactions to your chosen book considering its themes, characters, plot elements, etc. The point here is to document YOUR responses to a given piece of literature. What makes you like or dislike a book? What grabs your attention? The response essay should follow MLA guidelines for formatting (double spaced, 12-point Times New Roman font, 1” margins, with proper heading information, and page numbers with last name on top right). Improperly formatted papers will also lose points. Response essays are due the first day of classes. Step 3: During the first week of classes you will work together with others who read the same book to create and deliver a presentation that will educate and interest the rest of the class in the book’s content, literary merits, and author. Invisible Man By Ralph Ellison The nameless narrator of the novel describes growing up in a black community in the South, attending a Negro college from which he is expelled, moving to New York and becoming the chief spokesman of the Harlem branch of "the Brotherhood", and retreating amid violence and confusion to the basement lair of the Invisible Man he imagines himself to be. -

The Temple Murals: the Life of Malcolm X by Florian Jenkins

THE TEMPLE MURALS: THE LIFE OF MALCOLM X BY FLORIAN JENKINS HOOD MUSEUM OF ART | CUTTER-SHABAZZ ACADEMIC AFFINITY HOUSE | DARTMOUTH COLLEGE PREFACE The Temple Murals: The Life of Malcolm X by Florian Arts at Dartmouth on January 25, 1965, just one month a bed of grass, his head lifted in contemplation; across Jenkins has been a Dartmouth College treasure for before his tragic assassination. Seven years later, the room, above the fireplace, his face appears in many forty years, and we are excited to reintroduce it with the students in the College’s Afro-American Society invited angles and perspectives, with colors that are not absolute publication of this brochure, the research that went into Jenkins to create a mural in their affinity house, which but nuanced, suggesting the subject’s inner mysteries its contents, and the new photographs of the murals that they had just rededicated as the El Hajj Malik El Shabazz and anxieties, reflecting our own. illustrate it. Painted during a five-month period in 1972 Temple, after the name and title that Malcolm X had The murals also point out how starkly we differ from in the Cutter-Shabazz affinity house at Dartmouth, the adopted in 1964 after returning from his pilgrimage in Malcolm, who is rendered in contrasts in color, especially mural speaks to a potent moment in American history, Mecca. Now under the care of the Hood Museum of Art, above the door threshold. A white-masked specter one connected to events both in the life of civil rights The Temple Murals are powerful works that remind us of stands behind a black gunman, holding the gun toward leader Malcolm X and the moment of Dartmouth history the strength of individual activist voices, which Jenkins Malcolm as a horrified, blurred-face bystander watches in which the mural was created. -

The Autobiography of Malcolm X: As Told to Alex Haley

[PDF] The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Malcolm X, Alex Haley, Attallah Shabazz - pdf download free book The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley PDF Download, Free Download The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Ebooks Malcolm X, Alex Haley, Attallah Shabazz, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Full Collection, PDF The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Free Download, Read Online The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Ebook Popular, PDF The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Full Collection, online free The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley, Download Online The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Book, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Malcolm X, Alex Haley, Attallah Shabazz pdf, the book The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley, Download pdf The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley, Download The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley E-Books, Download The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Online Free, Read Best Book The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Online, Pdf Books The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley, Read The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Full Collection, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Free Download, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Free PDF Online, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Ebook Download, The Autobiography Of Malcolm X: As Told To Alex Haley Book Download, CLICK HERE FOR DOWNLOAD Decades of first exposure tools and life touch quickly encourages some london 's understanding of the border in the context of anyone who has destroyed her life and through his status of fantastical wisdom. -

By Any Means Necessary

MALCOLM X BY ANY MEANS NECESSARY A Biography by WALTER DEAN MYERS NEW YORK Xiii Excerpts from The Autobiography of Malcolm X, by Malcolm X, with the assistance of Alex Haley. Copyright © 1964 by Alex Haley and Malcolm X. Copyright © 1965 by Alex Haley and Betty Shabazz. Reprinted by permission of Random House Inc. Excerpts from Malcolm X Speaks, copyright © 1965 by Betty Shabazz and Pathfinder Press. All Rights Reserved. Reprinted by permission of Pathfinder Press. “Great Bateleur” is used by permission of Wopashitwe Mondo Eyen we Langa. If you purchased this book without a cover, you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher, and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.” Copyright © 1993 by Walter Dean Myers All rights reserved. Published by Scholastic Focus, a division of Scholastic Inc., Publishers since 1920. SCHOLASTIC, SCHOLASTIC FOCUS, and associated logos are trademarks and/ or registered trademarks of Scholastic Inc. The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third- party websites or their content. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For information regarding permission, write to Scholastic Inc., Attention: Permissions Department, 557 Broadway, New York, NY 10012. ISBN 978-1- 338- 30985-0 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 20 21 22 23 24 Printed in the U.S.A.