The Hedgehog and Wnt/β-Catenin System Machinery Mediate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Molecular Characterization of Clonal Human Renal Forming Cells Cohen-Zontag Osnat , Gershon Rotem , Harari-Steinberg Orit , Kant

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.05.978254; this version posted March 6, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Molecular characterization of clonal human renal forming cells Cohen-Zontag Osnat1,7,*, Gershon Rotem1,7,*, Harari-Steinberg Orit1,7,*, Kanter Itamar4, Omer Dorit1,7 , Pleniceanu Oren1,7, Tam Gal4, Oriel Sarit4, Ben-Hur Herzl8,9 , Katz Guy1,3,5,7, Zohar Dotan2,7, Kalisky Tomer4,#, Dekel Benjamin1, 6,7,#,^, Pode- Shakked Naomi1,3,7,#. 1Pediatric Stem Cell Research Institute, Edmond and Lily Safra Children's Hospital, Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel 2Dept of Urology, Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel 3The Talpiot Medical Leadership Program, Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel 4Faculty of Engineering and Bar-Ilan Institute of Nanotechnology and Advanced Materials (BINA), Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel. 5The Joseph Buchman Gynecology and Maternity Center, Sheba Medical Center, Tel- Hashomer, Israel 6Division of Pediatric Nephrology, Edmond and Lily Safra Children's Hospital, Sheba Medical Center, Tel-Hashomer, Israel 7Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv, Israel 8L.E.M. Laboratory of Early Detection, Nes Ziona, Israel 9Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Assaf Harofeh Medical Center, Tzrifin, Israel *These first authors contributed equally to this work #These senior authors contributed equally to this work ^Correspondence: Benjamin Dekel MD, PhD Pediatric Stem Cell Research Institute Edmond & Lily Safra Children's Hospital, Sheba Medical Center E-mails: [email protected] or [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.05.978254; this version posted March 6, 2020. -

Human Kidney Clonal Proliferation Disclose Lineage-Restricted Precursor Characteristics

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Human kidney clonal proliferation disclose lineage‑restricted precursor characteristics Osnat Cohen‑Zontag1,7,10, Rotem Gershon1,7,10, Orit Harari‑Steinberg1,7,10, Itamar Kanter4, Dorit Omer1,7, Oren Pleniceanu1,7, Gal Tam4, Sarit Oriel4, Herzel Ben‑Hur8,9, Guy Katz1,3,5,7, Zohar Dotan2,7, Tomer Kalisky4,11, Benjamin Dekel1,6,7,11* & Naomi Pode‑Shakked1,3,7,11 In‑vivo single cell clonal analysis in the adult mouse kidney has previously shown lineage‑restricted clonal proliferation within varying nephron segments as a mechanism responsible for cell replacement and local regeneration. To analyze ex‑vivo clonal growth, we now preformed limiting dilution to generate genuine clonal cultures from one single human renal epithelial cell, which can give rise to up to 3.4 * 106 cells, and analyzed their characteristics using transcriptomics. A comparison between clonal cultures revealed restriction to either proximal or distal kidney sub‑lineages with distinct cellular and molecular characteristics; rapidly amplifying de‑diferentiated clones and a stably proliferating cuboidal epithelial‑appearing clones, respectively. Furthermore, each showed distinct molecular features including cell‑cycle, epithelial‑mesenchymal transition, oxidative phosphorylation, BMP signaling pathway and cell surface markers. In addition, analysis of clonal versus bulk cultures show early clones to be more quiescent, with elevated expression of renal developmental genes and overall reduction in renal identity markers, but with an overlapping expression of nephron segment identifers and multiple identity. Thus, ex‑vivo clonal growth mimics the in‑vivo situation displaying lineage‑restricted precursor characteristics of mature renal cells. These data suggest that for reconstruction of varying renal lineages with human adult kidney based organoid technology and kidney regeneration ex‑vivo, use of multiple heterogeneous precursors is warranted. -

G Protein-Coupled Receptors

S.P.H. Alexander et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G protein-coupled receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology (2015) 172, 5744–5869 THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16: G protein-coupled receptors Stephen PH Alexander1, Anthony P Davenport2, Eamonn Kelly3, Neil Marrion3, John A Peters4, Helen E Benson5, Elena Faccenda5, Adam J Pawson5, Joanna L Sharman5, Christopher Southan5, Jamie A Davies5 and CGTP Collaborators 1School of Biomedical Sciences, University of Nottingham Medical School, Nottingham, NG7 2UH, UK, 2Clinical Pharmacology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 0QQ, UK, 3School of Physiology and Pharmacology, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TD, UK, 4Neuroscience Division, Medical Education Institute, Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, University of Dundee, Dundee, DD1 9SY, UK, 5Centre for Integrative Physiology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH8 9XD, UK Abstract The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2015/16 provides concise overviews of the key properties of over 1750 human drug targets with their pharmacology, plus links to an open access knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands (www.guidetopharmacology.org), which provides more detailed views of target and ligand properties. The full contents can be found at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/ 10.1111/bph.13348/full. G protein-coupled receptors are one of the eight major pharmacological targets into which the Guide is divided, with the others being: ligand-gated ion channels, voltage-gated ion channels, other ion channels, nuclear hormone receptors, catalytic receptors, enzymes and transporters. These are presented with nomenclature guidance and summary information on the best available pharmacological tools, alongside key references and suggestions for further reading. -

Multi-Functionality of Proteins Involved in GPCR and G Protein Signaling: Making Sense of Structure–Function Continuum with In

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2019) 76:4461–4492 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-019-03276-1 Cellular andMolecular Life Sciences REVIEW Multi‑functionality of proteins involved in GPCR and G protein signaling: making sense of structure–function continuum with intrinsic disorder‑based proteoforms Alexander V. Fonin1 · April L. Darling2 · Irina M. Kuznetsova1 · Konstantin K. Turoverov1,3 · Vladimir N. Uversky2,4 Received: 5 August 2019 / Revised: 5 August 2019 / Accepted: 12 August 2019 / Published online: 19 August 2019 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 Abstract GPCR–G protein signaling system recognizes a multitude of extracellular ligands and triggers a variety of intracellular signal- ing cascades in response. In humans, this system includes more than 800 various GPCRs and a large set of heterotrimeric G proteins. Complexity of this system goes far beyond a multitude of pair-wise ligand–GPCR and GPCR–G protein interactions. In fact, one GPCR can recognize more than one extracellular signal and interact with more than one G protein. Furthermore, one ligand can activate more than one GPCR, and multiple GPCRs can couple to the same G protein. This defnes an intricate multifunctionality of this important signaling system. Here, we show that the multifunctionality of GPCR–G protein system represents an illustrative example of the protein structure–function continuum, where structures of the involved proteins represent a complex mosaic of diferently folded regions (foldons, non-foldons, unfoldons, semi-foldons, and inducible foldons). The functionality of resulting highly dynamic conformational ensembles is fne-tuned by various post-translational modifcations and alternative splicing, and such ensembles can undergo dramatic changes at interaction with their specifc partners. -

G Protein‐Coupled Receptors

S.P.H. Alexander et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: G protein-coupled receptors. British Journal of Pharmacology (2019) 176, S21–S141 THE CONCISE GUIDE TO PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20: G protein-coupled receptors Stephen PH Alexander1 , Arthur Christopoulos2 , Anthony P Davenport3 , Eamonn Kelly4, Alistair Mathie5 , John A Peters6 , Emma L Veale5 ,JaneFArmstrong7 , Elena Faccenda7 ,SimonDHarding7 ,AdamJPawson7 , Joanna L Sharman7 , Christopher Southan7 , Jamie A Davies7 and CGTP Collaborators 1School of Life Sciences, University of Nottingham Medical School, Nottingham, NG7 2UH, UK 2Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Department of Pharmacology, Monash University, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia 3Clinical Pharmacology Unit, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, CB2 0QQ, UK 4School of Physiology, Pharmacology and Neuroscience, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TD, UK 5Medway School of Pharmacy, The Universities of Greenwich and Kent at Medway, Anson Building, Central Avenue, Chatham Maritime, Chatham, Kent, ME4 4TB, UK 6Neuroscience Division, Medical Education Institute, Ninewells Hospital and Medical School, University of Dundee, Dundee, DD1 9SY, UK 7Centre for Discovery Brain Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, EH8 9XD, UK Abstract The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2019/20 is the fourth in this series of biennial publications. The Concise Guide provides concise overviews of the key properties of nearly 1800 human drug targets with an emphasis on selective pharmacology (where available), plus links to the open access knowledgebase source of drug targets and their ligands (www.guidetopharmacology.org), which provides more detailed views of target and ligand properties. Although the Concise Guide represents approximately 400 pages, the material presented is substantially reduced compared to information and links presented on the website. -

FZD10 Carried by Exosomes Sustains Cancer Cell Proliferation

Article FZD10 Carried by Exosomes Sustains Cancer Cell Proliferation Maria Principia Scavo 1,*, Nicoletta Depalo 2, Federica Rizzi 2, Chiara Ingrosso 2, Elisabetta Fanizza 2,3, Annarita Chieti 1, Caterina Messa 4, Nunzio Denora 2,5, Valentino Laquintana 5, Marinella Striccoli 2, Maria Lucia Curri 2,3 and Gianluigi Giannelli 1,6,* 1 Personalized Medicine Laboratory, National Institute of Gastroenterology “S. De Bellis”, Via Turi 27, Castellana Grotte, 70013 Bari, Italy 2 Institute for Chemical and Physical Processes (IPCF)‐CNR SS Bari, Via Orabona 4, 70126 Bari, Italy 3 Dipartimento di Chimica, Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro, Via Orabona 4, 70126 Bari, Italy 4 Laboratory of Clinical Biochemistry, National Institute of Gastroenterology “S. De Bellis”, Via Turi 27, Castellana Grotte, 70013 Bari, Italy 5 Dipartimento di Farmacia, Scienze del Farmaco, Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro, Via Orabona 4, 70126 Bari, Italy 6 National Institute of Gastroenterology “S. De Bellis”, Scientific Direction, Via Turi 27, Castellana Grotte 70013 Bari, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.P.S.); [email protected] (G.G.); Tel.: +39‐080‐4994697 (M.P.S.) Received: 8 July 2019; Accepted: 23 July 2019; Published: 25 July 2019 Abstract: Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are involved in intercellular communication during carcinogenesis, and cancer cells are able to secrete EVs, in particular exosomes containing molecules, that can be transferred to recipient cells to induce pathological processes and significant modifications, as metastasis, increase of proliferation, and carcinogenesis evolution. FZD proteins, a family of receptors comprised in the Wnt signaling pathway, play an important role in carcinogenesis of the gastroenteric tract. -

Wnt/Rspondin/Β-Catenin Signals Control Axonal Sorting and Lineage Progression in Schwann Cell Development

Wnt/Rspondin/β-catenin signals control axonal sorting and lineage progression in Schwann cell development Tamara Grigoryana, Simone Steina, Jingjing Qia, Hagen Wendeb, Alistair N. Garrattc, Klaus-Armin Naved, Carmen Birchmeierb, and Walter Birchmeiera,1 aCancer Research Program and bNeuroscience Program, Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine, 13125 Berlin, Germany; cCenter for Anatomy, Charité University Hospital, 10117 Berlin, Germany; and dDepartment of Neurogenetics, Max Planck Institute for Experimental Medicine, 37075 Göttingen, Germany Edited by Thomas C. Südhof, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA, and approved September 26, 2013 (received for review June 2, 2013) During late Schwann cell development, immature Schwann cells organs (24–27). A role of Rspondins and Lgr4–6 receptors in SC segregate large axons from bundles, a process called “axonal ra- development has not been studied. dial sorting.” Here we demonstrate that canonical Wnt signals play Here we define a temporal window of Wnt/β-catenin activity a critical role in radial sorting and assign a role to Wnt and Rspon- and its role in SC lineage progression using mouse genetics and din ligands in this process. Mice carrying β-catenin loss-of-function cell culture techniques. Conditional loss-of-function (LOF) and mutations show a delay in axonal sorting; conversely, gain-of-function gain-of-function (GOF) mutations of β-catenin in mouse SCs mutations result in accelerated sorting. Sorting deficits are accom- produce converse phenotypes: a delay and an acceleration of panied by abnormal process extension, differentiation, and aber- axonal sorting, respectively. Using cultured primary SCs and rant cell cycle exit of the Schwann cells. -

A Possible Role of FZD10 Delivering Exosomes Derived from Colon

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article A Possible Role of FZD10 Delivering Exosomes Derived from Colon Cancers Cell Lines in Inducing Activation of Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition in Normal Colon Epithelial Cell Line Maria Principia Scavo 1,* , Federica Rizzi 2,3 , Nicoletta Depalo 2,* , Elisabetta Fanizza 2,3 , Chiara Ingrosso 2, Maria Lucia Curri 2,3 and Gianluigi Giannelli 4 1 Personalized Medicine Laboratory, National Institute of Gastroenterology “S. De Bellis” Research Hospital, Via Turi 27, Castellana Grotte, 70013 Bari, Italy 2 Institute for Chemical-Physical Processes (IPCF)-CNR SS Bari, Via Orabona 4, 70125 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (F.R.); [email protected] (E.F.); [email protected] (C.I.); [email protected] (M.L.C.) 3 Dipartimento di Chimica, Università degli Studi di Bari Aldo Moro, Via Orabona 4, 70125 Bari, Italy 4 Scientific Direction, National Institute of Gastroenterology “S. De Bellis” Research Hospital, Via Turi 27, Castellana Grotte, 70013 Bari, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (M.P.S.); [email protected] (N.D.); Tel.: +39-080-4994697 (M.P.S.); +39-080-5442027 (N.D.) Received: 11 August 2020; Accepted: 11 September 2020; Published: 13 September 2020 Abstract: Exosomes belong to the family of extracellular vesicles released by every type of cell both in normal and pathological conditions. Growing interest in studies indicates that extracellular vesicles, in particular, the fraction named exosomes containing lipids, proteins and nucleic acid, represent an efficient way to transfer functional cargoes between cells, thus combining all the other cell–cell interaction mechanisms known so far. -

WNT Signalling in Chronic Lung Diseases

Thorax Online First, published on April 17, 2017 as 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209753 State of the art review ‘WNT-er is coming’: WNT signalling in chronic lung Thorax: first published as 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209753 on 17 April 2017. Downloaded from diseases H A Baarsma,1 M Königshoff1,2 1Comprehensive Pneumology ABSTRACT involved in the phosphorylation and subsequent Center, Helmholtz Center Chronic lung diseases represent a major public health degradation of β-catenin. Binding of a specific WNT Munich, Ludwig Maximilians University Munich, University problem with only limited therapeutic options. An ligand (eg, WNT-3A) to one of the Frizzled recep- Hospital Grosshadern, Member important unmet need is to identify compounds and tors (FZD1 through FZD10) and subsequent activa- of the German Center for Lung drugs that target key molecular pathways involved in the tion of the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related Research (DZL), Munich, pathogenesis of chronic lung diseases. Over the last proteins 5 and 6 (LRP5/6) co-receptors triggers an Germany 2 decade, there has been extensive interest in investigating intracellular signalling cascade, which results in Division of Pulmonary ‘β ’ Sciences and Critical Care Wingless/integrase-1 (WNT) signalling pathways; and inactivation of the -catenin destruction complex . Medicine, Department of WNT signal alterations have been linked to pulmonary Hence, cytosolic β-catenin can accumulate, translo- Medicine, University of disease pathogenesis and progression. Here, we cate to the nucleus and, in association with T cell Colorado School of Medicine, comprehensively review the cumulative evidence for WNT factor/lymphoid enhancer factor-1 (TCF/LEF) Aurora, Colorado, USA pathway alterations in chronic lung pathologies, including family of transcription factors, induce specific gene 1 Correspondence to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary arterial expression (figure 1). -

Adenylyl Cyclase 2 Selectively Regulates IL-6 Expression in Human Bronchial Smooth Muscle Cells Amy Sue Bogard University of Tennessee Health Science Center

University of Tennessee Health Science Center UTHSC Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations (ETD) College of Graduate Health Sciences 12-2013 Adenylyl Cyclase 2 Selectively Regulates IL-6 Expression in Human Bronchial Smooth Muscle Cells Amy Sue Bogard University of Tennessee Health Science Center Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uthsc.edu/dissertations Part of the Medical Cell Biology Commons, and the Medical Molecular Biology Commons Recommended Citation Bogard, Amy Sue , "Adenylyl Cyclase 2 Selectively Regulates IL-6 Expression in Human Bronchial Smooth Muscle Cells" (2013). Theses and Dissertations (ETD). Paper 330. http://dx.doi.org/10.21007/etd.cghs.2013.0029. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Graduate Health Sciences at UTHSC Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (ETD) by an authorized administrator of UTHSC Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Adenylyl Cyclase 2 Selectively Regulates IL-6 Expression in Human Bronchial Smooth Muscle Cells Document Type Dissertation Degree Name Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Program Biomedical Sciences Track Molecular Therapeutics and Cell Signaling Research Advisor Rennolds Ostrom, Ph.D. Committee Elizabeth Fitzpatrick, Ph.D. Edwards Park, Ph.D. Steven Tavalin, Ph.D. Christopher Waters, Ph.D. DOI 10.21007/etd.cghs.2013.0029 Comments Six month embargo expired June 2014 This dissertation is available at UTHSC Digital Commons: https://dc.uthsc.edu/dissertations/330 Adenylyl Cyclase 2 Selectively Regulates IL-6 Expression in Human Bronchial Smooth Muscle Cells A Dissertation Presented for The Graduate Studies Council The University of Tennessee Health Science Center In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy From The University of Tennessee By Amy Sue Bogard December 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Amy Sue Bogard. -

Human Frizzled-10 / FZD10 Protein (His Tag)

Human Frizzled-10 / FZD10 Protein (His Tag) Catalog Number: 16045-H08H General Information SDS-PAGE: Gene Name Synonym: CD350; FZ-10; Fz10; FzE7; hFz10 Protein Construction: A DNA sequence encoding the human FZD10 (NP_009128.1) (Met1- Gly161) was expressed with a polyhistidine tag at the C-terminus. Source: Human Expression Host: HEK293 Cells QC Testing Purity: > 95 % as determined by SDS-PAGE Endotoxin: Protein Description < 1.0 EU per μg of the protein as determined by the LAL method Frizzled-10, also known as Fz-10, CD350 and FZD10, is a multi-pass Stability: membrane protein which belongs to theG-protein coupled receptor Fz/Smo family. Frizzled-10 / FZD10 is abundantly expressed in the cerebellum, Samples are stable for up to twelve months from date of receipt at -70 ℃ followed by cerebral cortex, medulla and spinal cord; very low levels in total brain, frontal lobe, temporal lobe and putamen. It is weakly expressed in Predicted N terminal: Ile 21 adult brain, heart, lung, skeletal muscle, pancreas, spleen and prostate. Molecular Mass: Frizzled-10 / FZD10 is a receptor for Wnt proteins. Most of frizzled receptors are coupled to the beta-catenin canonical signaling pathway, The recombinant human FZD10 consists of 152 amino acids and predicts which leads to the activation of disheveled proteins, inhibition of GSK-3 a molecular mass of 17.5 KDa. It migrates as an approximately 25.4 KDa kinase, nuclear accumulation of beta-catenin and activation of Wnt target band in SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions. genes. A second signaling pathway involving PKC and calcium fluxes has been seen for some family members, it is not yet clear if it represents a Formulation: distinct pathway or if it can be integrated in the canonical pathway, as PKC seems to be required for Wnt-mediated inactivation of GSK-3 kinase. -

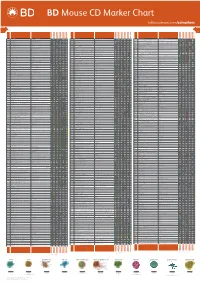

Mouse CD Marker Chart Bdbiosciences.Com/Cdmarkers

BD Mouse CD Marker Chart bdbiosciences.com/cdmarkers 23-12400-01 CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD Alternative Name Ligands & Associated Molecules T Cell B Cell Dendritic Cell NK Cell Stem Cell/Precursor Macrophage/Monocyte Granulocyte Platelet Erythrocyte Endothelial Cell Epithelial Cell CD1d CD1.1, CD1.2, Ly-38 Lipid, Glycolipid Ag + + + + + + + + CD104 Integrin b4 Laminin, Plectin + DNAX accessory molecule 1 (DNAM-1), Platelet and T cell CD226 activation antigen 1 (PTA-1), T lineage-specific activation antigen 1 CD112, CD155, LFA-1 + + + + + – + – – CD2 LFA-2, Ly-37, Ly37 CD48, CD58, CD59, CD15 + + + + + CD105 Endoglin TGF-b + + antigen (TLiSA1) Mucin 1 (MUC1, MUC-1), DF3 antigen, H23 antigen, PUM, PEM, CD227 CD54, CD169, Selectins; Grb2, β-Catenin, GSK-3β CD3g CD3g, CD3 g chain, T3g TCR complex + CD106 VCAM-1 VLA-4 + + EMA, Tumor-associated mucin, Episialin + + + + + + Melanotransferrin (MT, MTF1), p97 Melanoma antigen CD3d CD3d, CD3 d chain, T3d TCR complex + CD107a LAMP-1 Collagen, Laminin, Fibronectin + + + CD228 Iron, Plasminogen, pro-UPA (p97, MAP97), Mfi2, gp95 + + CD3e CD3e, CD3 e chain, CD3, T3e TCR complex + + CD107b LAMP-2, LGP-96, LAMP-B + + Lymphocyte antigen 9 (Ly9),