2014-Xx-Xx Brian Johnson Post

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Premiererne Eastmancolor(?)

Muo, Ma San. Udi: Panorama. Prem: 15.3.76 World Cinema. Karatevold. DERSU UZALA Dersu Uzala. USSR/Japan 1975. P-selskab: Sovex- port/Mosfilm. Instr: Akira Kurosawa. Manus: Akira Kurosawa, Yuri Nagibin. Efter: rejseskildring af Vladimir Arsenjev (1872-1930), da. overs. 1946: »Jægeren fra den sibiriske urskov«. Foto: Asakadru Nakat, Yuri Gantman, Fjodor Dobrovravov. Farve: Premiererne Eastmancolor(?). Medv: Maxim Munzuk (Dersu Uzala), Yuri Nagibin (Arsenjev). Længde: 137 min. 3840 m. Censur: Rød. Udi: Posthusteatret. Prem: 1.1.-31.3.76/ved Claus Hesselberg 15.3.76 Alexandra. Tilkendt en Oscar som bedste udenlandske film. Anm. Kos. 130. DET FRÆKKE ER OGSÅ GODT Quirk. USA. Farve: Eastmancolor(?). Længde: 75 min. 2000 m. Censur: Hvid. Fb.u.16. Udi: Dansk- Anvendte forkortelser: Svensk. Prem: 23.2.76 Carlton. Porno. Adapt: = Adaption Komp: = Komponist DIAMANTKUPPET Ark: = Filmarkitekt Kost: = Kostumer Diamonds. USA/lsrael 1975. P-selskab: AmeriEuro Arr: = Musikarrangør Medv: = Medvirkende skuespillere Productions. P: Menahem Golan. Ex-P: Harry N. As-P: = Associate Producer P: Producere Blum. As-P: Yoram Globus. P-leder: Arik Dichner. Instr: Instr-ass: = P-leder: = Produktionsleder Menahem Golan. Zion Chen, Ass: Assistent Shmuel Firstenberg, Roger Richman. Manus: David Dekor: = Scenedekorationer Prem: = Dansk premiere Paulsen, Menahem Golan, Ken Globus. Efter: for Dir: = Dirigent P-selskab: = Produktionsselskab tælling af Menahem Golan. Foto: Adam Greenberg. Dist: = Udlejer i oprindelsesland P-sup: = Produktions-superviser Farve: Eastmancolor. Klip: Dov Hoenig. Ark: Kuli Ex-P: = Executive Producer P-tegn: = Produktionstegner (design) Sander. Dekor: Alfred Gershoni. Sp-E: Hanz Kram Foto: = Cheffotograf Rekvis: = Rekvisitør sky. Musik: Roy Budd. Sang: »Diamonds« af Roy Budd, Jack Fishman. Solister: The Three Degrees. -

Saudades Do Futuro: O Cinema De Ficção Científica Como Expressão Do Imaginário Social Sobre O Devir

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS DEPARTAMENTO DE SOCIOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SOCIOLOGIA TESE DE DOUTORADO SAUDADES DO FUTURO: O CINEMA DE FICÇÃO CIENTÍFICA COMO EXPRESSÃO DO IMAGINÁRIO SOCIAL SOBRE O DEVIR Autora: Alice Fátima Martins Orientador: Prof. João Gabriel L. C. Teixeira (UnB) Banca: Prof. Paulo Menezes (USP) Prof. Julio Cabrera (UnB) Profª. Fernanda Sobral (SOL/UnB) Prof. Brasilmar Ferreira Nunes (SOL/UnB) Suplentes: Profª. Lourdes Bandeira (SOL/UnB) Prof. Roberto Moreira (SOL/UnB) Profª. Angelica Madeira (SOL/UnB) Profª. Ana Vicentini (CEPPAC/UnB) Profª. Mariza Veloso (SOL/UnB) 2 AGRADECIMENTOS Ao CNPq, pelo apoio financeiro a este trabalho; Ao Prof. João Gabriel L. C. Teixeira, orientador desta tese, companheiro inestimável nesse caminho acadêmico; Aos professores doutores que aceitaram o convite para compor esta banca: Prof. Paulo Menezes, Prof. Julio Cabrera, Profª. Fernanda Sobral, Prof. Brasilmar Ferreira Nunes; Aos suplentes da banca: Profª. Lourdes Bandeira, Prof. Roberto Moreira, Profª. Angélica Madeira, Profª. Ana Vicentini, Profª. Mariza Veloso; Ao Prof. Sergio Paulo Rouanet, que compôs a banca de qualificação, e cujas sugestões foram incorporadas à pesquisa, além das preciosas interlocuções ao longo do percurso; Aos Professores Eurico A. Gonzalez C. Dos Santos, Sadi Dal Rosso e Bárbara Freitag, com quem tive a oportunidade e o privilégio de dialogar, nas disciplinas cursadas; À equipe da Secretaria do Departamento de Sociologia/SOL/UnB, aqui representados na pessoa do Sr. Evaldo A. Amorim; À Professora Iria Brzezinski, pelo incentivo científico-acadêmico, sempre confraterno; À Professora Maria F. de Rezende e Fusari, pelos sábios ensinamentos, quanta saudade... Ao Professor Otávio Ianni, pelas sábias sugestões, incorporadas ao trabalho; Ao Professor J. -

Las Adaptaciones Cinematográficas De Cómics En Estados Unidos (1978-2014)

UNIVERSITAT DE VALÈNCIA Facultat de Filologia, Traducció i Comunicació Departament de Teoria dels Llenguatges i Ciències de la Comunicació Programa de Doctorado en Comunicación Las adaptaciones cinematográficas de cómics en Estados Unidos (1978-2014) TESIS DOCTORAL Presentada por: Celestino Jorge López Catalán Dirigida por: Dr. Jenaro Talens i Dra. Susana Díaz València, 2016 Por Eva. 0. Índice. 1. Introducción ............................................................................................. 1 1.1. Planteamiento y justificación del tema de estudio ....................... 1 1.2. Selección del periodo de análisis ................................................. 9 1.3. Sinergias industriales entre el cine y el cómic ........................... 10 1.4. Los cómics que adaptan películas como género ........................ 17 2. 2. Comparación entre los modos narrativos del cine y el cómic .......... 39 2.1. El guion, el primer paso de la construcción de la historia ....... 41 2.2. La viñeta frente al plano: los componentes básicos esenciales del lenguaje ........................................................................................... 49 2.3. The gutter ................................................................................. 59 2.4. El tiempo .................................................................................. 68 2.5. El sonido ................................................................................... 72 3. Las películas que adaptan cómics entre 1978 y 2014 ........................... 75 -

1 Hp0103 Roy Ward Baker

HP0103 ROY WARD BAKER – Transcript. COPYRIGHT ACTT HISTORY PROJECT 1989 DATE 5th, 12th, 19th, 26th, October and 6th November 1989. A further recording dated 16th October 1996 is also included towards the end of this transcript. Roy Fowler suggests this was as a result of his regular lunches with Roy Ward Baker, at which they decided that some matters covered needed further detail. [DS 2017] Interviewer Roy Fowler [RF]. This transcript is not verbatim. SIDE 1 TAPE 1 RF: When and where were you born? RWB: London in 1916 in Hornsey. RF: Did your family have any connection with the business you ultimately entered? RWB: None whatsoever, no history of it in the family. RF: Was it an ambition on your part or was it an accidental entry eventually into films? How did you come into the business? RWB: I was fairly lucky in that I knew exactly what I wanted to do or at least I thought I did. At the age of something like fourteen I’d had rather a chequered upbringing in an educa- tional sense and lived in a lot of different places. I had been taken to see silent movies when I was a child It was obviously premature because usually I was carried out in scream- ing hysterics. There was one famous one called The Chess Player which was very dramatic and German and all that. I had no feeling for films. I had seen one or two Charlie Chaplin films which people showed at children's parties in those days on a 16mm projector. -

Premiererne Robert Crawford

ley, Ted Kierscey, Dorse A. Lanpher, James L. George, Dick Lucas. Ark: Don Griffith. (Dansk version: Musik: Bent Fabricius-Bjerre) Musik: Artie Butler. Sange: »The Journey«, »Rescue Aid Society«, »Tomorrow Is Another Day« af Carol Connors, Ayn Robbins. »Someone’s Waiting for You« af Sammy Fain, Carol Connors, Ayn Rob bins. Solist: Shelby Filnt. »The U.S. Air Force« af Premiererne Robert Crawford. Medv: (stemmer) Preben Kaas 1.10-31.12.78/ved Claus Hesselberg (Bernard), Susanne Bruun-Koppel (Bianca), Kir sten Rolffes (Medusa), Benny Hansen (Snus), Elin Reimer (Ellie Mae), Olaf Nielsen (Luke), Claus Ryskjær (Albatrossen Orville), Helge Kjæ- ruIff-Schmidt (Rufus), Nicla Ursin (Penny), Bjørn Watt-Boolsen (Chariman), Jess Ingerslev (Kom mentator). Længde: 77 min., 2055 m. Censur: Rød. Udi: Columbia-Fox. Prem: 26.12.78 Metro pol, Ballerup, Rialto II, BIO TRIO. Anm. Kos. 140. Anvendte forkortelser: BETTY BOOP SKANDALER Adapt: = Adaption Komp: = Komponist Betty Boobs Scnadals. USA 1928-1934. Filmene er: 1928: »Koko’s Earth Kontrol« P-selskab: Out Ark: = Filmarkitekt Kost: = Kostumer of the Inkwell. P: Max Fleischer. 1930: »Swing, Arr: = Musikarrangør Medv: = Medvirkende skuespillere You Sinners«. P-selskab: Talkartoon. P: Max As-P: = Associate Producer P: = Producere Fleischer. Instr: Dave Fleischer. 1931: »Bimbo’s Ass: = Assistent P-leder: = Produktionsleder Initiation« P-selskab: Talkartoon. P: Max Fleis Dekor: = Scenedekorationer Prem: = Dansk premiere cher. Instr: Dave Fleischer. 1932: »Minnie the Dir: = Dirigent P-selskab: = Produktionsselskab Moocher«. P-selskab: Talkatoon. Instr: Dave Dist: = Udlejer i oprindelsesland P-sup: = Produktions-superviser Fleischer. Sange: »Minnie the Moocher« og »Tiger Rag« m. Cab Calloway og hans orkester. Ex-P: = Executive Producer P-tegn: = Produktionstegner (design) 1933: »Stoopnocracy«. -

Starlog Photo Guidebook Special Effects Vol 3

Norman Jacobs and Kerry O'Quinn present By David Hutchison Art Director: Cheh N. Low Designer: Robert Sefcik Art Staff: Laura O’Brien, Karen L. Hodell Production Assistants: Susan Adamo, John Clayton, Stuart Matranga ABOUT THE COVER: Front Cover, clockwise from top right: 1) Superman is up, up and away via Zoran Perisic’s Zoptic front projection technique. 2) Live laser effects under the supervision of Derek Meddings on Moonraker. 3) Bran Ferren’s optical enhancement of Dick Smith’s makeup in Altered States. 4) Doug Trumbull pauses a moment with one of the droids from his Silent Running. 5) Miniature from The Black Hole , effects by Art Cruickshank, Peter Ellenshaw, Danny Lee and Eustace Lycett. Back Cover, clockwise from top: 1) Miniature sequence from Thunderbirds, “End of the Road,” special effects supervised by Derek Meddings. 2) One of the optical printers at John Dykstra’s Apogee Co. 3) The model “Galactica” rigged for filming on the Dykstraf lex motion control system. David Robin and Don Dow are shown next to the model at Apogee. 4) Leon Harris’ conceptual art for the original alien saucer sequence at the end of Disney’s Wat- cher In the Woods. This sequence was never filmed. A STARLOG PRESS PUBLICATION 475 Park Avenue South New York, N.Y. 10016 Entire contents of STARLOG’s Photoguide Book to Special Ef- fects Vol. 3 is Copyright © 1981 by Starlog Press, Inc. All rights reserved. Reprinting or copying in part or in whole without the written permission of the publishers is strictly forbidden. Printed in Singapore. ISBN: 0-931064-39-2 PREFACE his is the third volume in the STARLOG Photo Guide- book Series on Special Effects. -

INFINITY Magazine Ghoulish Publishing Ltd 29 Cheyham Way, South Cheam, Surrey, SM2 7HX 4 INFINITY

THE MAGAZINE BEYOND YOUR IMAGINATION www.infinitymagazine.co.uk THE MAGAZINE BEYOND YOUR IMAGINATION 04 DOUBLE-SIDED POSTER INSIDE! ONLY £3.99 PLUS: T2, 3D - ROBERT PATRICK TALKS, 60s SPY-FI 007 IN QUATERMASS AND THE PIT, DR WHO, REVIEWS SPACE JOHN BRUNNER, NEWS, & MUCH MORE… THE AVENGERS RISE OF THE SUPERMACHINES: BLUE THUNDER AIRWOLF THE HONOR STREETHAWK BLACKMAN AND MORE… YEARS INFINITY ISSUE 4 - £3.99 04 9772514 36500 5 Buffalo Books [email protected] Talking about Ken Russell 550 pages £95 (deluxe) / £35 (standard) It took ten years to write but it only takes two years to read it. Hundreds of exclusive interviews with Russell and his crews, including twenty-four people who worked on he Devils. A 13-year-old Elvis Presley fan explores the solar system in a home-made spaceship. An adventure matched in danger only by his new-found fame. Starburst: “A love letter to childhood innocence. Grown-ups who haven’t quite grown up yet will absolutely love it. Should be the next big thing.” 176 pages £7 Understanding Gary Numan 134 pages (paperback) £7 he Moving Picture Boy Gallery Gary Numan: An Annotated Six English Filmmakers 322 pages £50 Scrapbook 318 pages £60 / £30 (Conversations with Michael Winner, he Moving Picture Girl Gallery he Warholian talent who Clive Donner, Lindsay Anderson, he Lemon Popsicle Book 220 pages £40 changed the music of the world Mike Hodges, Ken Russell, 302 pages £55/£25 A history of child ilm actors with a single inger. Kevin Brownlow on Chaplin) 286 pages colour £28 / B&W £13.50 04 THE MAGAZINE BEYOND -

XI Festival Internacional De Cinema E Vídeo De Ambiente Serra Da Estrela Seia Portugal

cineeco2005 XI festival internacional de cinema e vídeo de ambiente serra da estrela seia_portugal membro fundador da ASSOCIAÇÃO DE FESTIVAIS DE CINEMA DE MEIO AMBIENTE (EFFN - ENVIRONMENTAL FILM FESTIVAL NETWORK) juntamente com cinemambiente . environmental film festival . turim . itália festival internacional del medi ambient sant feliu de guíxols . barcelona . espanha ecocinema . festival internacional de cinema ambiental . grécia parceiro dos festival internacional de cinema e vídeo ambiental goiás . brasil festival internacional de cinema do ambiente washington . eua vizionária . international video festival . siena . itália wild and scenic environmental film festival . nevada city . eua em formação plataforma atlântica de festivais de ambiente de colaboração com festival internacional de cinema e vídeo ambiental goiás . brasil festival de são vicente . cabo verde extensão do cineeco: centro das artes . casa das mudas . calheta . madeira Edição: CineEco Título: Programa do CineEco’2005 XI Festival Internacional de Cinema e Vídeo de Ambiente da Serra da Estrela Coordenação, design gráfico e concepção da capa segundo imagem de “Madagáscar”, de Eric Darnell: Lauro António Tiragem: 1000 exemplares Impressão: Cromotipo Artes Gráficas Depósito Legal: 116857/97 | 3 | cineeco2005 Saudação do Presidente da Câmara de Seia O Cine’Eco – Festival Internacional de Cinema e Vídeo de Ambiente da Serra da Estrela é, no plano cultural, uma importante marca do esforço que a Câmara Municipal tem desenvolvido e vai continuar a desenvolver, em benefício da qualidade do nosso ambiente. No ano em que o Cine’Eco avança para a sua 11ª edição, estão a dar-se, finalmente, passos decisivos para o tratamento de todos os esgotos domésticos e industriais. Em 2006, os nossos rios e ribeiras vão voltar a correr sem poluição. -

Premiererne Barbara Boulter, S

som f.eks. at pirke lig ud af ruder eller promovering af statsmagten som effektiv (Hilma Randel), Ernst Gunther (Jacob Randel), hjælpe fæhoveder udenfor terroristers underholder udi det militante, der stiger Chatarina Larsson (Marta Brehm), Per Mattson (Ture Torne), Hans Ernback (Fortælleren). skudvidde. Reaktionsmønstret faldt på frem. Terroristen er altid for tidligt på Længde: 100 min., 2755 m. Censur: Fb.u.16. plads i Villabyerne, en veltilpashed af tryg færde til at blive tappet 100% som under Prem: 26.12.77 Dagmar. Udi: Dagmar. Indspillet i hed over de besatte gader. holdning. Ordensmagten er meget flinkere Stockholm. Anm. Kos. 137. »The Day the Earth Stood Still« hyppede til at vente på du finder din gode tilskuer AMSTERDAM KILL, THE nogle kartofler i de fjerne 50’ere, men det plads. Den er måske heller ikke bange for The Amsterdam Kill. Arb.titel: Kill him in Amster var storhedsvanvittige udenrigsdrømme. at kæmpe mod vindmøller. dam. Hong Kong 1977. P-selskab: Golden Har Her i »Skytten« er det den indadvendte Peter J. Erichsen vest/Fantasti c Films S.A. P: André Morgan. Ex-P: Raymond Chow. P-sup William Chulack. P-le der: Madatena Chan, David Chan, Onno Plan ting. Instr: Robert Clouse. Instr-ass: Louis Shek- tin, Chaplin Chang. Stunt-instr: Alan Stuart. Ma nus: Robert Clouse, Gregory Teifer. Efter fortæl ling af Gregory Teifer. Foto: Alan Hume. Farve: Technicolor. Format: Cinemascope. Klip: Alan Holzman, Gina Brown. P-tegn: John Blezard, K.S. Chen. Dekor: Lee Jim, Jim Blocker. Kost: Premiererne Barbara Boulter, S. H. Chu, Gwen Capetanos. 1.10.-31.12.77/ved Claus Hesselberg Sp-E: Gene Grigg. -

Starlog Magazine Issue

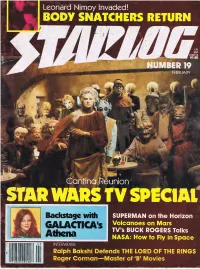

Leonard Nimoy Invaded! I BODY SNATCHERS RETURN UMBER 19 FEBRUARY , w /. -*i ¥ r- Gantina Reunion TT A!AVJd«L' Backstase with SUPERMAN on the Horizon GALACTICAs Volcanoes on Mars Athena TV's BUCK ROGERS Talks NASA: How to Fly in Space 02 INTERVIEWS: Ralph Bakshi Defends THE LORD OF THE RINGS Roger Gorman— Master of 'B' Movies '18 96"491 12 1 . ASTRONOMY will orient your life to the sky. With the help of Sky Almanac , you'll be able to look up and say, "There's Venus! And over there is . Jupiter . and that's Saturn!!" You'll discover what you can see with a telescope with Star Dome , as you come to know the zodiac and STRONOMV bright familiar constellations in the sky. ASTRONOMY also has popular. monthly departments such as Equipment Atlas, vour R guide to telescopes; Gazer s Gazette to help you I ^!l ONo my know what you're looking at; Astro-News with all the latest, and Astro-Mart. Become a subscriber to ASTRONOMY and join us in our monthly journey through space and time. You'll find in its pages a whole new world of wonders and experience that will ********influence your entire life. Special Offer to Starlog Readers To welcome you as a subscriber to If you've been impressed all your life with ASTRONOMY, we'll send you — absolutely stars that punch you in the eye on a warm free — a gigantic full color wall poster summer night, you should be reading depicting the 22nd century exploration of ASTRONOMY magazine. If the wonder and the Antares star system. -

Catalogo Fantafestival 2011

31.FANTAFESTIVAL Roma 9 • 19 giugno 2011 nuovo cinema aquila • AUDiToRium conciliaZione • caSa Del cinema Ministero Per 31.FAntAFESTIVAL Coordinamento artistico Il Fantafestival ringrazia: onsiderato uno dei più prestigiosi e popolari festival di genere in i Beni e Le Attività Marcello rossi CuLturALi Direttori BiM Distribuzione Europa, il Fantafestival compie quest’anno il suo trentunesimo Ministro Adriano Pintaldi & Curatore della B MOVIES, Giancarlo Galan Alberto ravaglioli pAnorAmiCA BoLERO FiLM anniversario. dei giovAni Autori itAliAni FrAMe BY FrAMe Comitato promotore Domenico vitucci MeDusA FiLM In qualità di direttori, abbiamo sempre concepito questo evento Direzione Generale Dario Argento MinervA PiCtures Cromano come un ideale rendez-vous per tutti i cultori del cinema fantastico per il Cinema Pupi Avati Coordinamento organizzativo reDArK Lamberto Bava Maria Luisa Celani tHe MoB Direttore Generale Mel Brooks t.M. 2005 provenienti non solo da tutta Italia ma anche dall’Europa. nicola Borrelli roger Corman Ufficio Stampa 20tH CenturY FoX La XXXI edizione, oltre alla tradizionale sezione informativa, quella delle Lloyd Kaufman Cristina Borsatti universAL STUDios sir Christopher Lee WAve DISTRIBuzione anteprime internazionali, e la grande vetrina sul nuovo cinema italiano di Carlo rambaldi Responsabile copie reGione lazio George A.romero e segreteria Gabriele Albanesi genere, vuole caratterizzarsi con una grande retrospettiva sul cinema italiano vittorio storaro Carlo Carosi Laura Argento Presidente stefano Bessoni fantastico degli -

“Rama” Vistavision Cameras Rama Research: Why Cameras?

ILM Technirama “Rama” VistaVision Cameras Rama Research: Why Cameras? The movie camera has a unique place in a film’s production. In the hierarchy of equipment, it is king. Millions of dollars are spent on the various elements of a major film, and all are eventually distilled down to what plays out on a 2” piece of ground glass in the heart of a camera. No camera, no movie. Some of the most memorable shots in 20th century cinema were captured in the movements of these VistaVision beasts. ILM was all about breaking new ground. The I could have stood for Innovation. The technology needed to put groundbreaking visuals on the screen didn’t exist, so it was created. Like a musician tinkering with a guitar to get the right sound, ILM hot-rodded their gear. The modifications serve as unique “tells” that can be used to track and identify the equipment. VistaVision and Technirama: A Primer VistaVision was the dominant format used for visual effects work at ILM from its inception through the late 1980s. Originally developed by Paramount in the 1950s, the VistaVision format takes traditional 35mm negative and turns it on its side, allowing you to expose a larger negative area and essentially have more resolution in the frame. This is necessary for visual effects work where the image will be duplicated, sometimes several times, in an optical compositing process. A copy is never as sharp as the original, so beginning with a larger negative ensures that the final composited effects shots would be just as sharp as the rest of the film, which was shot in the traditional “4-perf” 35mm (anamorphic) format.