1 Hp0103 Roy Ward Baker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robertson Davies Fifth Business Fifth Business Definition: Those Roles Which, Being Neither Those of Hero Nor Heroine, Confidant

Robertson Davies Fifth Business Fifth Business Definition: Those roles which, being neither those of Hero nor Heroine, Confidante nor Villain, but which were nonetheless essential to bring about the Recognition or the denouement, were called the Fifth Business in drama and opera companies organized according to the old style; the player who acted these parts was often referred to as Fifth Business. —Tho. Overskou, Den Daaske Skueplads I. Mrs. Dempster 1 My lifelong involvement with Mrs. Dempster began at 8 o’clock p.m. on the 27th of December, 1908, at which time I was ten years and seven months old. I am able to date the occasion with complete certainty because that afternoon I had been sledding with my lifelong friend and enemy Percy Boyd Staunton, and we had quarrelled, because his fine new Christmas sled would not go as fast as my old one. Snow was never heavy in our part of the world, but this Christmas it had been plentiful enough almost to cover the tallest spears of dried grass in the fields; in such snow his sled with its tall runners and foolish steering apparatus was clumsy and apt to stick, whereas my low-slung old affair would almost have slid on grass without snow. The afternoon had been humiliating for him, and when Percy as humiliated he was vindictive. His parents were rich, his clothes were fine, and his mittens were of skin and came from a store in the city, whereas mine were knitted by my mother; it was manifestly wrong, therefore, that his splendid sled should not go faster than mine, and when such injustice showed itself Percy became cranky. -

HATTIE JACQUES Born Josephine Edwina Jacques on February 7" 1922 She Went on to Become a Nationally Recognised Figure in the British Cinema of the 1950S and 60S

Hattie Jacaues Born 127 High St 1922 Chapter Twelve HATTIE JACQUES Born Josephine Edwina Jacques on February 7" 1922 she went on to become a nationally recognised figure in the British cinema of the 1950s and 60s. Her father, Robin Jacques was in the army and stationed at Shorncliffe Camp at the time of her birth. The Register of Electors shows the Jacques family residing at a house called Channel View in Sunnyside Road. (The register shows the name spelled as JAQUES, without the C. Whether Hattie changed the spelling or whether it was an error on the part of those who printed the register I don’t know) Hattie, as she was known, made her entrance into the world in the pleasant seaside village of Sandgate, mid way between Folkestone to the east and Hythe to the west. Initially Hattie trained as a hairdresser but as with many people of her generation the war caused her life to take a different course. Mandatory work saw Hattie first undertaking nursing duties and then working in North London as a welder Even in her twenties she was of a generous size and maybe as defence she honed her sense of humour after finding she had a talent for making people laugh. She first became involved in show business through her brother who had a job as the lift operator at the premises of the Little Theatre located then on the top floor of 43 Kings Street in Covent Garden. At end of the war the Little Theatre found itself in new premises under the railway arches below Charing Cross Station. -

WALLACE, (Richard Horatio) Edgar Geboren: Greenwich, Londen, 1 April 1875

WALLACE, (Richard Horatio) Edgar Geboren: Greenwich, Londen, 1 april 1875. Overleden: Hollywood, USA, 10 februari 1932 Opleiding: St. Peter's School, Londen; kostschool, Camberwell, Londen, tot 12 jarige leeftijd. Carrière: Wallace was de onwettige zoon van een acteur, werd geadopteerd door een viskruier en ging op 12-jarige leeftijd van huis weg; werkte bij een drukkerij, in een schoen- winkel, rubberfabriek, als zeeman, stukadoor, melkbezorger, in Londen, 1886-1891; corres- pondent, Reuter's, Zuid Afrika, 1899-1902; correspondent, Zuid Afrika, London Daily Mail, 1900-1902 redacteur, Rand Daily News, Johannesburg, 1902-1903; keerde naar Londen terug: journalist, Daily Mail, 1903-1907 en Standard, 1910; redacteur paardenraces en later redacteur The Week-End, The Week-End Racing Supplement, 1910-1912; redacteur paardenraces en speciaal journalist, Evening News, 1910-1912; oprichter van de bladen voor paardenraces Bibury's Weekly en R.E. Walton's Weekly, redacteur, Ideas en The Story Journal, 1913; schrijver en later redacteur, Town Topics, 1913-1916; schreef regelmatig bijdragen voor de Birmingham Post, Thomson's Weekly News, Dundee; paardenraces columnist, The Star, 1927-1932, Daily Mail, 1930-1932; toneelcriticus, Morning Post, 1928; oprichter, The Bucks Mail, 1930; redacteur, Sunday News, 1931; voorzitter van de raad van directeuren en filmschrijver/regisseur, British Lion Film Corporation. Militaire dienst: Royal West Regiment, Engeland, 1893-1896; Medical Staff Corps, Zuid Afrika, 1896-1899; kocht zijn ontslag af in 1899; diende bij de Lincoln's Inn afdeling van de Special Constabulary en als speciaal ondervrager voor het War Office, gedurende de Eerste Wereldoorlog. Lid van: Press Club, Londen (voorzitter, 1923-1924). Familie: getrouwd met 1. -

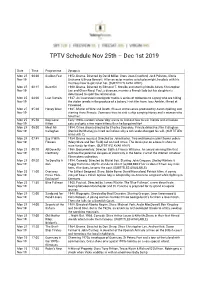

TPTV Schedule Nov 25Th – Dec 1St 2019

TPTV Schedule Nov 25th – Dec 1st 2019 Date Time Programme Synopsis Mon 25 00:00 Sudden Fear 1952. Drama. Directed by David Miller. Stars Joan Crawford, Jack Palance, Gloria Nov 19 Grahame & Bruce Bennett. After an actor marries a rich playwright, he plots with his mistress how to get rid of her. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 02:15 Beat Girl 1960. Drama. Directed by Edmond T. Greville and starring Noelle Adam, Christopher Nov 19 Lee and Oliver Reed. Paul, a divorcee, marries a French lady but his daughter is determined to spoil the relationship. Mon 25 04:00 Last Curtain 1937. An insurance investigator tracks a series of robberies to a gang who are hiding Nov 19 the stolen jewels in the produce of a bakery. First film from Joss Ambler, filmed at Pinewood. Mon 25 05:20 Honey West 1965. Matter of Wife and Death. Classic crime series produced by Aaron Spelling and Nov 19 starring Anne Francis. Someone tries to sink a ship carrying Honey and a woman who hired her. Mon 25 05:50 Dog Gone Early 1940s cartoon where 'dog' wants to find out how to win friends and influence Nov 19 Kitten cats and gets a few more kittens than he bargained for! Mon 25 06:00 Meet Mr 1954. Crime drama directed by Charles Saunders. Private detective Slim Callaghan Nov 19 Callaghan (Derrick De Marney) is hired to find out why a rich uncle changed his will. (SUBTITLES AVAILABLE) Mon 25 07:45 Say It With 1934. Drama musical. Directed by John Baxter. Two well-loved market flower sellers Nov 19 Flowers (Mary Clare and Ben Field) fall on hard times. -

From Dimitrios with Love Ian Fleming’S Cold War Revision of Eric Ambler’S a Coffn for Ififrr Fos

From Dimitrios with Love Ian Fleming’s Cold War Revision of Eric Ambler’s A Coffn for ififrr fos LUCAS TOWNSEND One of the most recognisable titles of Cold War popular fction is certainly Ian Fleming’s 1957 no el From Russia With Love! Listed among American $resident %ohn F! &ennedy’s top ten fa ourite no els in Life magazine and later mar(ing Sean Connery’s second flm appearance as %ames *ond+ Russia occupies a cross, roads of multilateral Cold War culture, becoming a -uintessential mar(er of the deadlocked political tensions bet.een /ast and West! Russia .as a noticeable de, parture from the successful formula Fleming de eloped in the four *ond no els that preceded it0 Casino Royale+ Live and Let Die+ Moonraker+ and Diamonds Are For- ever! In Russia+ *ond’s chief 1 orders him to Istanbul on a mission to 2pimp for England3 4Fleming 5615b, 1177 and seduce the beautiful So iet cipher cler( 8a, tiana 9omano a. In e:change, 8atiana ofers a cutting-edge So iet encryption machine, the )pe(tor! As the reader learns from the opening section of the no el+ this is an elaborate ploy+ a 2honey trap3 laid by the So iet <nion’s )1/9)=1 intelligence branch to cripple the reputation of the *ritish Secret Ser, ice in a murder-suicide se: scandal in ol ing their best agent! Russia’s uni-ue 1 #s Fleming defnes it+ 2)1/9)= is a contraction of >)miert )pionam ?Смерть Шпионам@+’ .hich means >Aeath to )pies’3 45615b+ 577! )1/9)= 4СМЕРШ 7 .as a real col, laborati e department of se eral )oviet counterintelligence agencies! Lucas Townsend is .n /A 0.n*i*.)e in Englis1 .) 2lori*. -

RAMO CAN SAVE the WORLD Ays the Bishop of Chelmsford

RADIO PICTORIAL, May 12,1939. No. 278 rTJLXEMB0URG Registered at the G.P.O. as a Newspaper NORMANDY PARIS : LYONS : EIREANN PROGRAMMES May 14-May 20 EVERY FRIDAY lipt* RAMO CAN SAVE THE WORLD ays The Bishop of Chelmsford Interview with Radio Favourite NORMAN LONG We're the News -Narks" by the ESTERN BROS. LISTENING in the BALKANS All about the ROYAL BROADCASTS B.B.C. JACK HULBERT and PROGRAMME CICELY COURTNEIDGE SEE PAGE 37 GUIDE Photo :Courtesy Goumont British RADIO PICTORIAL May 12, 1939 DON CARLOS RADIO'S Golden Tenor can be heard in a new series of programmes presented by Armour's from Normandy on Wednesdays at 9.15 a.m. and Luxem- bourg, Thursdays, 10.15 a.in. Supporting are Eddie Carroll and his Orchestra, Michael Moore, the impersonator, and such famous guest artistes as Leonard Henry, Hazell and Day, Bennett and Williams, Rudy Starita... 2 May 12, 1939 RADIO PICTORIAL we..-.-e-ere....- No. 278 ...........-.. RADIO PICTORIALviEiktiffretijoi The All -Family Radio Magazine Published by BERNARD JONES PUBLICATIONS, LTD. 37-38 Chancery Lane. W.C.2. HOLborn 6158 MANAGING EDITOR K. P.HUNT ASST. EDITOR JESSIE E. KIRK IN THEY say the only time a IftE,41Rii certain singer ever got an encore was when he was born.He was a twin. Because,sweetheart,allB.B.C. AND now they tell us, though we announcers have tobe perfectlittle don't believeit,that Charlie We ran into a Scottish comedian gentlemen. Kunz has bought a bicycle with a and a strip -tease girl the other day, loud and soft pedal. -

Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE May 2016 Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network Laura Osur Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Osur, Laura, "Netflix and the Development of the Internet Television Network" (2016). Dissertations - ALL. 448. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/448 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract When Netflix launched in April 1998, Internet video was in its infancy. Eighteen years later, Netflix has developed into the first truly global Internet TV network. Many books have been written about the five broadcast networks – NBC, CBS, ABC, Fox, and the CW – and many about the major cable networks – HBO, CNN, MTV, Nickelodeon, just to name a few – and this is the fitting time to undertake a detailed analysis of how Netflix, as the preeminent Internet TV networks, has come to be. This book, then, combines historical, industrial, and textual analysis to investigate, contextualize, and historicize Netflix's development as an Internet TV network. The book is split into four chapters. The first explores the ways in which Netflix's development during its early years a DVD-by-mail company – 1998-2007, a period I am calling "Netflix as Rental Company" – lay the foundations for the company's future iterations and successes. During this period, Netflix adapted DVD distribution to the Internet, revolutionizing the way viewers receive, watch, and choose content, and built a brand reputation on consumer-centric innovation. -

From Real Time to Reel Time: the Films of John Schlesinger

From Real Time to Reel Time: The Films of John Schlesinger A study of the change from objective realism to subjective reality in British cinema in the 1960s By Desmond Michael Fleming Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 School of Culture and Communication Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Produced on Archival Quality Paper Declaration This is to certify that: (i) the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD, (ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, (iii) the thesis is fewer than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. Abstract The 1960s was a period of change for the British cinema, as it was for so much else. The six feature films directed by John Schlesinger in that decade stand as an exemplar of what those changes were. They also demonstrate a fundamental change in the narrative form used by mainstream cinema. Through a close analysis of these films, A Kind of Loving, Billy Liar, Darling, Far From the Madding Crowd, Midnight Cowboy and Sunday Bloody Sunday, this thesis examines the changes as they took hold in mainstream cinema. In effect, the thesis establishes that the principal mode of narrative moved from one based on objective realism in the tradition of the documentary movement to one which took a subjective mode of narrative wherein the image on the screen, and the sounds attached, were not necessarily a record of the external world. The world of memory, the subjective world of the mind, became an integral part of the narrative. -

3B Dymchurch St Mary's Bay and Romney Sands V01 DRAFT

EB 11.13b PROJECT: Shepway Heritage Strategy DOCUMENT NAME: Theme 3(b): Dymchurch, St Mary’s Bay and Romney Sands Version Status Prepared by Date V01 INTERNAL DRAFT F Clark 23.05.17 Comments – first draft of text. No illustrations, figures or photographs. Version Status Prepared by Date V02 Version Status Prepared by Date V03 Version Status Prepared by Date V04 Version Status Prepared by Date V05 1 | P a g e (3b) Dymchurch, St Mary’s Bay and Romney Sands 1. Summary Dymchurch, St Mary’s Bay and Romney Sands are popular destinations along the Shepway coastline for holidaymakers and day-trippers. Their attractive beaches, holiday parks and various other attractions have drawn in visitors and holidaymakers for a number of years and continue to do so today. The history of these areas is largely linked to the complex natural history of the Romney Marsh and the reclamation of land from the sea that has occurred over a number of centuries. The Romney Marsh today is now rich in heritage and natural biodiversity that constitutes a distinctive local landscape. The growth in seaside tourism and leisure time during the nineteenth century resulted in a rise in coastal resort towns along the Shepway coastline and by the twentieth century Dymchurch, St Mary’s Bay and Romney Sands all had popular holiday camps that were easily accessible by the Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch Railway that was opened in 1927. All of these areas continue today as popular seaside destinations and boast attractive beaches as well as a number of valuable heritage assets that relate to its history of smuggling, farming and defence of the coast. -

Suzanne Marwille – Women Film Pioneers Project

5/18/2020 Suzanne Marwille – Women Film Pioneers Project Suzanne Marwille Also Known As: Marta Schölerová Lived: July 11, 1895 - January 14, 1962 Worked as: film actress, screenwriter Worked In: Czechoslovakia, Germany by Martin Šrajer To date, there are only about ten women screenwriters known to have worked in the Czech silent film industry. Some of them are more famous today as actresses, directors, or entrepreneurs. This is certainly true of Suzanne Marwille, who is considered to be the first Czech female film star. Less known is the fact that she also had a talent for writing, as well as dramaturgy and casting. Between 1918 and 1937, she appeared in at least forty films and wrote the screenplays for eight of them. Born Marta Schölerová in Prague on July 11, 1895, she was the second of four daughters of postal clerk Emerich Schöler and his wife Bedřiška Peceltová (née Nováková). There is a scarcity of information about Marta’s early life, but we know that in June 1914, at the age of eighteen, she married Gustav Schullenbauer. According to the marriage registry held at the Prague City Archives, he was then a twenty-year-old volunteer soldier one year into his service in the Austrian-Hungarian army (Matrika oddaných 74). Four months later, their daughter—the future actress and dancer Marta Fričová—was born. The marriage lasted ten years, which coincided with the peak years of Marwille’s career. As was common at the time, Marwille was discovered in the theater, although probably not as a stage actress. While many unknowns still remain about this occasion, it was reported that film industry professionals first saw her sitting in the audience of a Viennese theater at the end of World War I (“Suzanne Marwille” 2). -

Gb 1456 Thomas

GERALD THOMAS COLLECTION GERALD THOMAS COLLECTION SCOPE AND CONTENT Documents relating to the career of director GERALD THOMAS (Born Hull 10/12/1920, died Beaconsfield 9/11/1993). When Gerald Thomas died, his producer partner of 40 years Peter Rogers said: ‘His epitaph will be that he directed all the Carry On films.’ Indeed, for an intense 20-year period Thomas directed the Carry On gang through their innuendo laden exploits, and became responsible, along with Rogers, for creating one of the most enduring and endearing British film series, earning him his place in British popular culture. Thomas originally studied to become a doctor, before war service with the Royal Sussex Regiment put paid to his medical career. When demobilised in 1946, he took a job as assistant in the cutting rooms of Two Cities Films at Denham Studios, where he took Assistant Editor credits on Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet (1948) and the John Mills thriller The October Man (1947). In 1949, he received his first full credit as editor, on the Margaret Lockwood melodrama Madness of the Heart (1949). During this time Peter Rogers had been working as associate producer with his wife, producer Betty Box, on such films as It’s Not Cricket (1949) and Don’t Ever Leave Me (1949). It was Venetian Bird in 1952 that first brought Thomas and Rogers together; Thomas employed as editor by director brother Ralph, and Rogers part of the producer team with Betty Box. Rogers was keen to form a director/producer pairing (following the successful example of Box and Ralph Thomas), and so gave Gerald his first directing credit on the Circus Friends (1956), a Children’s Film Foundation production. -

Theatre Archive Project Archive

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 349 Title: Theatre Archive Project: Archive Scope: A collection of interviews on CD-ROM with those visiting or working in the theatre between 1945 and 1968, created by the Theatre Archive Project (British Library and De Montfort University); also copies of some correspondence Dates: 1958-2008 Level: Fonds Extent: 3 boxes Name of creator: Theatre Archive Project Administrative / biographical history: Beginning in 2003, the Theatre Archive Project is a major reinvestigation of British theatre history between 1945 and 1968, from the perspectives of both the members of the audience and those working in the theatre at the time. It encompasses both the post-war theatre archives held by the British Library, and also their post-1968 scripts collection. In addition, many oral history interviews have been carried out with visitors and theatre practitioners. The Project began at the University of Sheffield and later transferred to De Montfort University. The archive at Sheffield contains 170 CD-ROMs of interviews with theatre workers and audience members, including Glenda Jackson, Brian Rix, Susan Engel and Michael Frayn. There is also a collection of copies of correspondence between Gyorgy Lengyel and Michel and Suria Saint Denis, and between Gyorgy Lengyel and Sir John Gielgud, dating from 1958 to 1999. Related collections: De Montfort University Library Source: Deposited by Theatre Archive Project staff, 2005-2009 System of arrangement: As received Subjects: Theatre Conditions of access: Available to all researchers, by appointment Restrictions: None Copyright: According to document Finding aids: Listed MS 349 THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT: ARCHIVE 349/1 Interviews on CD-ROM (Alphabetical listing) Interviewee Abstract Interviewer Date of Interview Disc no.