"An Arrow Aimed at the Heart" : the Vancouver Women's Caucus And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Schools and Boards Using Etms - October 23, 2020

List of Schools and Boards Using eTMS - October 23, 2020 Board Name School Name Algoma DSB ADSB Virtual Secondary School Algoma DSB Bawating Collegiate And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Superior Heights C and VS Algoma DSB White Pines Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Sault Ste Marie Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Elliot Lake Secondary School Algoma DSB North Shore Adult Education School Algoma DSB Central Algoma SS Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Sir James Dunn C And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Central Algoma Secondary School Algoma DSB Korah Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Michipicoten High School Algoma DSB North Shore Adolescent Education School Algoma DSB W C Eaket Secondary School Algoma DSB Algoma Education Connection Algoma DSB Chapleau High School Algoma DSB Hornepayne High School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB ALCDSB Summer School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Loyola Community Learning Centre-Con Ed Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Nicholson Catholic College Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB St Theresa Catholic Secondary School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Loyola Community Learning Centre Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB St Paul Catholic Secondary School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Regiopolis/Notre-Dame Catholic High School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Holy Cross Catholic Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Exeter Ctr For Employment And Learning NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB South Huron District High School Avon Maitland DSB Stratford Ctr For Employment and Learning NS Avon Maitland DSB Wingham Employment And Learning NS Avon Maitland -

Cynthia Flood Fonds (Msc 106)

Simon Fraser University Special Collections and Rare Books Finding Aid - Cynthia Flood fonds (MsC 106) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Printed: August 03, 2016 Language of description: English Rules for Archival Description Simon Fraser University Special Collections and Rare Books W.A.C. Bennett Library - Room 7100 Simon Fraser University 8888 University Drive Burnaby BC Canada V5A 1S6 Telephone: 778.782.8842 Email: [email protected] http://atom.archives.sfu.ca/index.php/fonds-msc-106-cynthia-flood-fonds Cynthia Flood fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Series descriptions .......................................................................................................................................... -

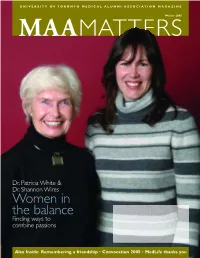

2005-Fall.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO MEDICAL ALUMNI ASSOCIATION MAGAZINE Winter 2005 MAAMATTERS Dr. Patricia White & Dr. Shannon Wires Women in the balance Finding ways to combine passions Also Inside: Remembering a friendship • Convocation 2005 • MedLife thanks you PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE D r. Suan-Seh Foo (Class of 1990) An honour, an obligation – A proud tradition We have a duty to ourselves to uphold what is best – a duty to our patients, a duty to the profession, a duty to our alma mater. alumni, we share a common his- to introduce the interim Dean of AS tory. Continuity and collegiality Medicine, Dr. Catharine Whiteside from are part of the MAA tradition and the fun- the Class of 1975. She will be our hon- damental thread that binds our genera- orary president, and I would like to assure tions together. They are the foundation her of our support. Dr. Flavio Habal from upon which we build and the sure plat- the Class of 1977 is the MAA’s new treas- form that allows us to spring forward to urer. It is important to me that we recog- the future. nize our past treasurer, Dr. Steven Tishler. So we are really not alone, unless we Steven has put a tremendous amount of choose to be. We are part of something work into husbanding our investments, greater – greater than ourselves. It is both overseeing expenditures in the office and a joyous and a humbling realization. It is ensuring that we do not become generous not without obligation. We have a duty to beyond our means. Thank you, Dr. -

Printable List of Laureates

Laureates of the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame A E Maude Abbott MD* (1994) Connie J. Eaves PhD (2019) Albert Aguayo MD(2011) John Evans MD* (2000) Oswald Avery MD (2004) F B Ray Farquharson MD* (1998) Elizabeth Bagshaw MD* (2007) Hon. Sylvia Fedoruk MA* (2009) Sir Frederick Banting MD* (1994) William Feindel MD PhD* (2003) Henry Barnett MD* (1995) B. Brett Finlay PhD (2018) Murray Barr MD* (1998) C. Miller Fisher MD* (1998) Charles Beer PhD* (1997) James FitzGerald MD PhD* (2004) Bernard Belleau PhD* (2000) Claude Fortier MD* (1998) Philip B. Berger MD (2018) Terry Fox* (2012) Michel G. Bergeron MD (2017) Armand Frappier MD* (2012) Alan Bernstein PhD (2015) Clarke Fraser MD PhD* (2012) Charles H. Best MD PhD* (1994) Henry Friesen MD (2001) Norman Bethune MD* (1998) John Bienenstock MD (2011) G Wilfred G. Bigelow MD* (1997) William Gallie MD* (2001) Michael Bliss PhD* (2016) Jacques Genest MD* (1994) Roberta Bondar MD PhD (1998) Gustave Gingras MD* (1998) John Bradley MD* (2001) Phil Gold MD PhD (2010) Henri Breault MD* (1997) Richard G. Goldbloom MD (2017) G. Malcolm Brown PhD* (2000) Jean Gray MD (2020) John Symonds Lyon Browne MD PhD* (1994) Wilfred Grenfell MD* (1997) Alan Burton PhD* (2010) Gordon Guyatt MD (2016) C H G. Brock Chisholm MD (2019) Vladimir Hachinski MD (2018) Harvey Max Chochnov, MD PhD (2020) Antoine Hakim MD PhD (2013) Bruce Chown MD* (1995) Justice Emmett Hall* (2017) Michel Chrétien MD (2017) Judith G. Hall MD (2015) William A. Cochrane MD* (2010) Michael R. Hayden MD PhD (2017) May Cohen MD (2016) Donald O. -

Liste Des Écoles Et Des Conseils Qui Utilisent Le Sgérn - 24 Juin 2021

Liste des écoles et des conseils qui utilisent le SGéRN - 24 juin 2021 Conseil École Algoma DSB ADSB Virtual Secondary School Algoma DSB Algoma Education Connection Algoma DSB Bawating Collegiate And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Central Algoma Secondary School Algoma DSB Central Algoma SS Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Chapleau High School Algoma DSB Elliot Lake Secondary School Algoma DSB Hornepayne High School Algoma DSB Korah Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Michipicoten High School Algoma DSB North Shore Adolescent Education School Algoma DSB North Shore Adult Education School Algoma DSB Sault Ste Marie Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Sir James Dunn C And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Superior Heights C and VS Algoma DSB W C Eaket Secondary School Algoma DSB White Pines Collegiate And Vocational School Avon Maitland DSB Avon Maitland District E-Learning Centre Avon Maitland DSB Avon Maitland DSB Summer School Avon Maitland DSB Bluewater SS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Central Huron Adult Learning NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Central Huron Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Dublin School - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Exeter Ctr For Employment And Learning NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB F E Madill Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Goderich District Collegiate Institute Avon Maitland DSB Listowel Adult Learning Centre NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Listowel District Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Milverton DHS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Mitchell Adult Learning Centre NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB Mitchell District High School Avon Maitland -

List of Schools and Boards Using Etms - July 16, 2019

List of Schools and Boards Using eTMS - July 16, 2019 Board Name School Name Algoma DSB Bawating Collegiate And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Superior Heights C and VS Algoma DSB White Pines Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Sault Ste Marie Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Elliot Lake Secondary School Algoma DSB North Shore Adult Education School Algoma DSB Central Algoma SS Adult Learning Centre Algoma DSB Sir James Dunn C And VS - CLOSED Algoma DSB Central Algoma Secondary School Algoma DSB Korah Collegiate And Vocational School Algoma DSB Michipicoten High School Algoma DSB North Shore Adolescent Education School Algoma DSB W C Eaket Secondary School Algoma DSB Algoma Education Connection Algoma DSB Chapleau High School Algoma DSB Hornepayne High School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB ALCDSB Summer School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Loyola Community Learning Centre-Con Ed Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Nicholson Catholic College Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB St Theresa Catholic Secondary School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Loyola Community Learning Centre Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB St Paul Catholic Secondary School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Regiopolis/Notre-Dame Catholic High School Algonquin and Lakeshore CDSB Holy Cross Catholic Secondary School Avon Maitland DSB Exeter Ctr For Employment And Learning NS - CLOSED Avon Maitland DSB South Huron District High School Avon Maitland DSB Stratford Ctr For Employment and Learning NS Avon Maitland DSB Wingham Employment And Learning NS Avon Maitland DSB Seaforth DHS Night School - CLOSED -

J-Fraser-Mustard-Fonds.Pdf

University of Toronto Archives J. Fraser Mustard Personal Records B2011-0010 Karen Suurtamm, 2012 Marnee Gamble, Revised 2014 Emily Sommers, revised 2019 © University of Toronto Archives and Records Management Services 2012 J. Fraser Mustard fonds University of Toronto Archives B2011-0010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Biographical sketch .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Biographical .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Series 2: Early scientific and medical career .............................................................................................. 7 Series 3: Correspondence .................................................................................................................................. 8 Series 4: Day planners ......................................................................................................................................... 9 Series 5: Travel files ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Series 6: Early presentations ........................................................................................................................ -

Public Accounts of the Province of Ontario for the Year Ended March 31, 1980

PUBLIC ACCOUNTS, 1979-80 OFFICE OF THE LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR Hon. Pauline McGibbon, Lieutenant Governor DETAILS OF EXPENDITURE Voted Salaries and Wanes ($72,148) Salaries and Wages under $30,000-64,293. Temporary Help Services ($7,855): Accounts under SI 0,000- 7,855. Employee Benefits ($10,371) Payments to the Treasurer of Ontario re: Canada Pension Plan, 808; Group Insurance, 201; Long Term Income Protection, 399; Ontario Health Insurance Plan, 1,919; Supplementary Health and Hospital Plan, 279; Dental Plan, 165; Public Service Superannuation Fund, 2,633; Payment on Unfunded Liability of the Public Service Superannuation Fund, 2,558; Superannuation Adjustment Fund, 576; Unemployment Insurance, 833. Other Payments ($35,685) Materials, Supplies, etc. ($5,685): Accounts under $20,000-5,685. Expenses ($30,000): Her Honour Pauline McGibbon, allowance for contingencies, 30,000. Total Other Payments 35,685 Summary of Expenditure Voted Salaries and Wages 72,148 Employee Benefits 10,371 Other Payments • 35.685 Total Expenditure, Office of the Lieutenant Governor $ 118,204 PUBLIC ACCOUNTS, 1979-80 OFFICE OF THE PREMIER Hon. William G. Davis, Premier and President of the Council DETAILS OF EXPENDITURE Voted Salaries and Wages ($1,228,492) Listed below are the salary rates of those employees on staff at March 31, where the annual rate is in excess of $30,000. Dr. E. E. Stewart Deputy Minister 59.000 Barnes, S. Y., 36,450; R. I. Beatty, 37,575; R. A. Cook, 34,275; P. L. Dale, 31 ,325; V. J. Devitt, 32.875; U. O. Ferdinand. 36,590; R. L. McNeil, 46,700; C. -

The Storied Career of the Storied Career Of

WINTER 2013 UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO MEDICAL ALUMNI ASSOCIATION MAGAZINE MAAMATTERS The storied career of DR. JOE GREENBERG CONVOCATION 2013 • THE NEW FACE OF CPD PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE DR. PETER KOPPLIN (1963) Coincidence, connections and campaigns DR. LAURENCE LEE (1976), AN ALUMNUS you may be a bit confused by the plethora from BC, recently sent us a terrific letter. of email and mail requests for donations. He explained that a good number of years Some come directly from us; the MAA is a ago he addressed his son’s Grade 5 class as separate, registered charitable organization part of career day. Fast forward to 2013 from the Faculty. Other email requests and as Laurence is looking at the front come from the Faculty; it promotes the cover of the spring 2013 issue of MAA large U of T “Boundless” fundraising Matters, he recognizes one of those same campaign, supporting student aid, research Grade 5 kids—who is now a U of T senior and infrastructure. The MAA’s mission Meds student. While it would be a stretch focuses on student aid only and keeping to consider that the defining influence on alumni connected. the student’s career choice was Laurence’s As 2013 wanes, I am happy to remind talk, it was still, as Milan Kundera writes, you that you are a graduate of a great medical the “beauty” of coincidence. school and one that is growing even better. PHOTOGRAPHY: KEVIN KELLY PHOTOGRAPHY: Fostering relationships among alumni, I hope that you will continue to support students and the Faculty of Medicine is an the MAA as we continue to support our important part of the MAA mandate. -

William Davis and the Road to Completion in Ontario's Catholic

CCHA, Historical Studies, 69 (2003), 7-33 William Davis and the Road to Completion in Ontario’s Catholic High Schools, 1971-1985 Robert DIXON In 1971 Premier William Davis responded negatively to the brief of the Ontario Separate School Trustees Association (OSSTA, now named the Ontario Catholic School Trustees’ Association, OCSTA) arguing for extension/completion of the separate school system to the end of high school.1 He gave five reasons for his position, which had the ring of conviction. Yet in 1984 he reversed his stance and announced that his government would be extending the separate school system to the end of grade thirteen. Why did he change government policy on the perennial separate school issue? Publications at the time and shortly thereafter conveyed the view that Cardinal G. Emmett Carter of the Archdiocese of Toronto finally persuaded his friend Davis to do so. Some political pundits added the idea that the premier was about to retire – he suddenly and without anyone’s knowledge made the decision and was able to announce extension and watch quietly from the sidelines as the storm of reactions took place in the media, at public hearings, at public school board meetings, and in the courts. This paper completely discounts such an interpretation. It will argue that Premier Davis for some time considered extending the separate school system and that he carefully consulted with representatives of the Ontario Catholic Conference of Bishops and with officials in the ministry of education before announcing the outlines of the new policy. Without discrediting the influence of Carter or of the premier’s retirement plans, it will also examine a number of reasons why Davis reversed his 1971 announcement in 1984. -

AR 2001 Layout Final

Annual Report.2001/2002 royal ontario museum Photograph courtesy of Chrisite’s Fine Art Auctioneers. Art Fine Photograph courtesy of Chrisite’s . the finest example of English marquetry in Canada. Piano—George III (2002.23.1)—Acquired through the Louise Hawley Stone Charitable Trust and with a grant approved by the Minister of Canadian Heritage under the terms of the Cultural Property Export and Import Act in February 2002. This piano, dated 1777, is the finest example of English marquetry (wood veneer) in Canada. The Louise Hawley Stone Charitable Trust was established in 1998 to support acquisitions and publications related to the ROM’s exhibitions and collections. Contents Report of the Chairman of the Board of Trustees and the Director and CEO 3 Message from the Chairman of the ROM Foundation Board of Directors 5 Royal Ontario Museum Board of Trustees 2001/2002 6 Royal Ontario Museum Foundation Board of Directors 2001/2002 7 Renaissance ROM 8 Message from the Vice-President, Collections and Research 13 Great Asian Dinosaurs! Unique Creatures from Russia’s Vaults 14 Message from the Chief Operating Officer 17 Programming 18 Exhibitions 20 Donors, Patrons, Sponsors 22 Publications by Museum Staff and Research Associates 37 ROM Financial Statements 43 ROM Foundation Financial Statements 54 Organizational Chart 60 Recent ROM Acquisitions 01.Western Art and Culture . the future centrepiece of the ROM’s new Bronze Age Greece gallery. Terracotta coffin (2002.22.1-.2)—Acquired through the Louise Hawley Stone Charitable Trust. A virtually intact larnax (terracotta sarcophagus) from the island of Crete, late Minoan Period III, c. -

GA 99 Luella Creighton Fonds

Special Collections, University of Waterloo Library Finding Aid : GA 99 Luella Creighton fonds. © Special Collections, University of Waterloo Library GA 99 : Creighton, Luella Bruce, 1901-. Special Collections, University of Waterloo Library. Page 1 GA 99 : Creighton, Luella Bruce, 1901- Luella Creighton fonds. - 1917-1990, predominant 1950-1990. - 1.5 m of textual records. - 71 photographs. Luella Bruce Creighton (1901-1996) was a Canadian author whose works, both fiction and non fiction, were published in the 1950's and 1960's. Born Luella Sanders Bruce on Aug. 25, 1901 in Stouffville, Ont., she taught in a rural school in 1920-1921 prior to attending Victoria College at the University of Toronto. She graduated with a BA in 1926 and married historian and writer Donald Creighton on June 23 of the same year. Her writings include High bright buggy wheels, McClelland & Stewart, 1951; Turn east, turn west, McClelland & Stewart, 1954; Canada, the struggle for empire (non-fiction), Dent, 1960; Canada, trial and triumph (non- fiction), Dent, 1963; Tecumseh, the story of the shawnee chief (juvenile biography), Macmillan, 1965; Miss Multipenny and Miss Crumb, Peal, 1966; The elegant Canadians (non- fiction), McClelland & Stewart, 1967; The hitching post, McClelland & Stewart, 1969. Luella Creighton died in 1996 [?]. The fonds contains a small amount of material documenting Luella Creighton's student days at Victoria College, University of Toronto, 1924-1926. Her personal life is further documented through a series of diaries, 1963-1990. Most of the textual material in the fonds, however, relates to her career as a writer of both fiction and non- fiction, and consists of corrrespondence with her publishers and readers, reviews, manuscripts and typescripts of both published and unpublished works.