Clare County Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Griffiths Valuation of Ireland

Dwyer_Limerick Griffiths Valuation of Ireland Surname First Name Townland Parish County Dwyer Patrick Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Ashroe Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer William Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Ellen Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer William Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Michael Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Ellen Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Ellen Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer William Cappanahanagh Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cloghnadromin Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cloghnadromin Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Cloghnadromin Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Coolbreedeen Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Coolbreedeen Abington Limerick Dwyer Patrick Coolbreedeen Abington Limerick Dwyer John Gleno Abington Limerick Dwyer John Gleno Abington Limerick Dwyer John Gleno Abington Limerick Dwyer James Gleno Knocklatteragh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Gleno Knocklatteragh Abington Limerick Dwyer James Gleno Knocklatteragh Abington Limerick Dwyer Catherine Gortavacoosh -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

A GUIDE to SEA ANGLING in the EASTERN FISHERIES REGION by Norman Dunlop

A GUIDE TO SEA ANGLING IN THE EASTERN FISHERIES REGION by Norman Dunlop Published by; the Eastern Regional Fisheries Board, 15A, Main Street, Blackrock, Co. Dublin. © Copyright reserved. No part of the text, maps or diagrams may be used or copied without the permission of the Eastern Regional Fisheries Board. 2009 Foreword I am delighted to welcome you to the Board’s new publication on sea fishing Ireland’s east and south east coast. Sea angling is available along the entire coastline from Dundalk in County Louth to Ballyteigue Bay in County Wexford. You will find many fantastic venues and a multitude of species throughout the region. Whether fishing from the shore or from a licenced charter boat there is terrific sport to be had, and small boat operators will find many suitable slipways for their vessels. At venues such as Cahore in Co. Wexford small boat anglers battle with fast running Tope, Smoothhound, and Ray. Kilmore Quay in South Wexford is a centre of excellence for angling boasting all types of fishing for the angler. There is a great selection of chartered boats and the facilities for small boat fishing are second to none. Anglers can go reef fishing for Pollack, Wrasse, Cod, and Ling. From springtime onwards at various venues shore anglers lure, fly, and bait fish for the hard fighting Bass, while specialist anglers target summer Mullet and winter Flounder. In recent years black bream have been turning up in good numbers in the Wexford area and this species has recently been added to the Irish specimen fish listing. -

Inspectors of Irish Fisheries

REPORT OF THE INSPECTORS OF IRISH FISHERIES ON THE SEA AND INLAND FISHERIES OF IRELAND, FOR 1885 |Presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty DUBLIN: PRINTED BY ALEX. THOM & CO. (Limited), 87, 88, & 89, ABBEY-STREET THE QUEEN’S PRINTING OFFICE, To Do purchased, either directly or through any Bookseller, from any of the following Agents, viz.: Messrs. Hansard, 13, Great Queen-street, W.C., and 32, Abingdon-street, Westminster; Messrs. Eyre and Spottiswoode East Harding-street, Fleet-street, and Sale Office, House of Lords; Messrs. Adam and Charles Black, of Edinburgh; Messrs. Alexander Thom and Co. (Limited), or Messrs. Hodges, Figgis, and Co., of Dublin. 1886. [C.^4809.] Price lOcZ. CONTENTS. Page REPORT, . .. ' . • • 3 APPENDIX, . * ’ • 49 Appendix No. Sea and Oyster Fisheries. 50 1. —Abstract of Returns from Coast Guard, . • • 51-56 2. —By-Laws in force, . • 56, 57 3. —Oyster Licenses revoked, ...•••• 4. —Oyster Licenses in force, .....•• 58-63 Irish Reproductive Loan Fund and Sea and Coast Fisheries,Fund. 5. —Proceedings foi’ year 1885, and Total Amount of Loans advanced, and Total Repayments under Irish Reproductive Loan Fund for eleven years ending 31st December, 1885, 62, 63 6. —Loans applied for and advanced under Sea and Coast Fisheries Fund for year ending 31st December, 1885, . ... 62 7. —Amounts available and applied for, 1885, ..,••• 63 8. —Herrings, Mackerel, and Cod, exported to certain places, . 64 9. —Return of Salted and Cured Fish imported in 1885, ...••• 64 Salmon Fisheries. 10. —License duties received in 1885, . • 65 11. Do. received in 1863 to 1885, 65 12. Do. -

Rathmichael Historical Record 2001 Published by Rathmichael Historical Society 2003 SECRETARY's REPORT—2001

CONTENTS Secretary's Report ........................................ • .... 1 25th-A GM.: ........................................................ 2 Shipwrecks in and around Dublin Bay..................... 5 The Rathdown Union Workhouse 1838-1923 .......... 10 Excavations of Rural Norse Settlements at Cherrywood ........................................................ 15 Outing to Dunsany Castle ...................................... 18 Outing to some Pre-historic Tombs ......................... 20 27th Summer School. Evening lectures .................. 21 Outing to Farmleigh House .................................... 36 Weekend visit to Athenry ....................................... 38 Diarmait MacMurchada ......................................... 40 People Places and Parchment ................................... 47 A New Look at Malton's Dublin, ............................. 50 D. Leo Swan An Appreciation ................................. 52 Rathmichael Historical Record 2001 Published by Rathmichael Historical Society 2003 SECRETARY'S REPORT—2001. Presented January 2002 2001 was another busy year for the society's members and committee. There were six monthly lectures, and evening course, four field trips, an autumn weekend away and nine committee meetings. The winter season resumed, following the AGM with a lecture in February by Cormac Louth on Shipwrecks around Dublin Bay. In March Eva 6 Cathaoir spoke to us on The Rathdown Union workhouse at Loughlinstown in the period 1838-1923 and concluded in April with John 6 Neill updating -

IRELAND! * ; ! ; ! ! ESTABLISHED 1783 ! N ! •! I FACILITIES for TRAVELLERS I + + ! •I at I I I Head Office: COLLEGE GREEN DUBLIN T S ! BELFAST

VOL. XXI. No. 9 JUNE, 1946 THREEPENCE THE MALL, WESTPORT. CO. AYO ~ ··•..1 ! ! · ~ i + DUBLIN ·t ;~ ~ •i i !; ; i; ; ! ; • ~ BANK OF IRELAND! * ; ! ; ! ! ESTABLISHED 1783 ! N ! •! i FACILITIES FOR TRAVELLERS i + + ! •i AT i i I Head Office: COLLEGE GREEN DUBLIN t s ! BELFAST .. CORK •. DERRY ~ RINEANNA i I U Where North meets South ~~ ~ ; AND tOO TOWNS THROUGHOUT IRELAND I + PHONE: DUBLIN 71371 (6 Lines) ; ! ! EVERY DESCRIPTION OF FOREIGN EXCHANGE BUSINESS ~ • Res£dent !Ifanager T. O'Sullivan TRANSACTED •! L~ - .t .J [food name in Gafe Sets 1 and Instantuneolls lratcr Boilers for Tea ][aking * Thc,'c .\ I' c llllHlc'!s to Huii cycry nccd antl in eye [' y <:apa,<:ity. STOCKIST AGENTS: Unrivalled for Cuisine and Service Superb Cuisine makes the Clarence wellU:; 51 DAWSON STREET, unrivalled and nppetising. The 'ervice, too, which is prompt and courteous, will please the CUBLlN PHONE 71563/4 most exacting pntron. 'Phone 76178 The CLARENCE HOTEL Dublin P('I'hr8, ,11 i,"frs, rld/l/frS. Grills. l10l ClI"boar(k Wr, _ O'Keell.·s •• I RISH TRAVEL Official Organ of the Irish Tourist JU~ E, 1946 5/- per Annum Post Free from Association and of the Irish Hotels Irish Tourist Association, O'Connell Federation Vol. XXI No. 9 street, Dublin Two New Ships for Irish English Crossing. The New Migration . Two 3,000 ton Great Western Railway steamers are Evidence of the new migration, consequent on war III construction at Birkenhead to replace war losses on and taxation charges elsewhere, is seen in the demand the Fishguard-Ireland passage. It is hoped that they for country residences now in many parts of Ireland. -

South Dublin Bay and River Tolka Estuary Special Protection Area (Site Code 4024)

North Bull Island Special Protection Area (Site Code 4006) & South Dublin Bay and River Tolka Estuary Special Protection Area (Site Code 4024) ≡ Conservation Objectives Supporting Document VERSION 1 National Parks & Wildlife Service October 2014 T AB L E O F C O N T E N T S SUMMARY PART ONE - INTRODUCTION ..................................................................... 1 1.1 Introductiion to the desiignatiion of Speciiall Protectiion Areas ........................................... 1 1.2 Introductiion to North Bullll Islland and South Dublliin Bay and Riiver Tollka Estuary Speciiall Protectiion Areas .................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Introductiion to Conservatiion Objjectiives........................................................................ 3 PART TWO – SITE DESIGNATION INFORMATION .................................................................... 5 2.1 Speciiall Conservatiion Interests of North Bullll Islland Speciiall Protectiion Area.................. 5 2.2 Speciiall Conservatiion Interests of South Dublliin Bay and Riiver Tollka Estuary Speciiall Protectiion Area .................................................................................................................. 8 PART THREE – CONSERVATION OBJECTIVES FOR NORTH BULL ISLAND SPA AND SOUTH DUBLIN BAY AND RIVER TOLKA ESTUARY SPA ....................................................... 11 3.1 Conservatiion Objjectiives for the non-breediing Speciiall Conservatiion Interests of North Bullll -

The Capuchin Annual and the Irish Capuchin Publications Office

1 Irish Capuchin Archives Descriptive List Papers of The Capuchin Annual and the Irish Capuchin Publications Office Collection Code: IE/CA/CP A collection of records relating to The Capuchin Annual (1930-77) and The Father Mathew Record later Eirigh (1908-73) published by the Irish Capuchin Publications Office Compiled by Dr. Brian Kirby, MA, PhD. Provincial Archivist July 2019 No portion of this descriptive list may be reproduced without the written consent of the Provincial Archivist, Order of Friars Minor Capuchin, Ireland, Capuchin Friary, Church Street, Dublin 7. 2 Table of Contents Identity Statement.......................................................................................................................................... 5 Context................................................................................................................................................................ 5 History ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Archival History ................................................................................................................................. 8 Content and Structure ................................................................................................................................... 8 Scope and content ............................................................................................................................. 8 System of arrangement .................................................................................................................... -

Download the Archive Issue 19

The Archive Contents Project Team Project Manager: Mary O’Driscoll 3 Nancy McCarthy – A Key to Cork’s Cultural History Research Director: Dr Clíona O’Carroll Annmarie McIntyre Editorial Advisor: Ciarán Ó Gealbháin Design/Layout: Dermot Casey Bygone Buildings Editorial Team: Ciarán Ó Gealbháin, Mary O’Driscoll, 4 Dr Margaret Steele, Stephen Dee, Seán Moraghan Aisling Byron Project Researchers: Tara Arpaia, Aisling Byron, Dermot Casey, Stephen Dee, Robert Galligan Long, Sweet Memories Penny Johnston, Louise Madden O’Shea, Tim 7 McCarthy, Annmarie McIntyre, Seán Moraghan, Laura Dr Margaret Steele Murphy, Dr Margaret Steele Water Monsters in Irish Folklore Acknowledgements 8 Dr Jenny Butler The Cork Folklore Project would like to thank: Dept of Social Protection, Susan Kirby; Management and staff of Northside Community Enterprises, Fr John 10 Bailiúchán Béaloidis Ghaeltacht Thír Chonaill O’Donovan, Noreen Hegarty; Roinn an Bhéaloidis / Dept Mícheál Ó Domhnaill of Folklore and Ethnology, University College Cork, Dr Stiofán Ó Cadhla, Dr Marie-Annick Desplanques, Dr Photo and a Story Clíona O’Carroll, Ciarán Ó Gealbháin, Bláthnaid Ní 11 Bheaglaoí and Colin MacHale; Cork City Council, Cllr Stephen Dee Kieran McCarthy; Cork City Heritage Officer, Niamh Twomey; Cork City and County Archives, Brian McGee; Cork and African Slavery Cork City Library, Local Studies; Michael Lenihan, Dr 12 Seán Moraghan Carol Dundon Disclaimer Sound Excerpts The Cork Folklore Project is a Dept of Social Protection 14 Stories from our archive funded joint initiative of Northside Community Enterprises Ltd & Dept of Folklore and Ethnology, University College Cork. Material in The Archive (including 16 Oral History as a Social Justice Tool photographs) remains copyright of the Project, unless Tara Arpaia otherwise indicated. -

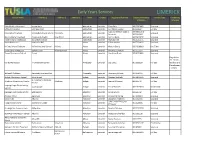

LIMERICK Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type Conditions of Service Attached

Early Years Services LIMERICK Service Name Address 1 Address 2 Address 3 Town County Registered Provider Telephone Number Service Type Conditions of Service Attached Little Buddies Preschool Knocknasna Abbeyfeale Limerick Clara Daly 085 7569865 Sessional Little Stars Creche Killarney Road Abbeyfeale Limerick Ann-Marie Huxley 068 30438 Full Day Catriona Sheeran Sandra 087 9951614/ Meenkilly Pre School Meenkilly National school Meenkilly Abbeyfeale Limerick Sessional Broderick 0879849039 Noreen Barry Playschool Community Centre New Street Abbeyfeale Limerick Noreen Barry 087 2499797 Sessional Teach Mhuire Montessori 12 Colbert Terrace Abbeyfeale Limerick Mary Barrett 086 3510775 Sessional Adare Playgroup Methodist Hall Adare Limerick Gillian Devery 085 7299151 Sessional Kilfinny School Childcare Kilfinny National School Kilfinny Adare Limerick Marion Geary 089 4196810 Part Time Little Gems Montessori Barley Grove Killarney Road Adare Limerick Veronica Coleman 061 355354 Sessional Tuogh Montessori School Tuogh Adare Limerick Geraldine Norris 085 8250860 Sessional Regulation 19 - Health, Karibu Montessori The Newtown Centre Annacotty Limerick Liza Eyres 061 338339 Full Day Welfare and Developmen t of Child Wilmot's Childcare Annacotty Business Park Annacotty Limerick Rosemary Wilmot 061 358166 Full Day Ardagh Montessori School Main Street Ardagh Limerick Martina McGrath 087 6814335 Sessional St. Coleman’s Childcare Kilcolman Community Creche Kilcolman Ardagh Limerick Joanna O'Connor 069 60770 Full Day Service Leaping Frogs Childminding Coolcappagh -

Sacred Space. a Study of the Mass Rocks of the Diocese of Cork and Ross, County Cork

Sacred Space. A Study of the Mass Rocks of the Diocese of Cork and Ross, County Cork. Bishop, H.J. PhD Irish Studies 2013 - 2 - Acknowledgements My thanks to the University of Liverpool and, in particular, the Institute of Irish Studies for their support for this thesis and the funding which made this research possible. In particular, I would like to extend my thanks to my Primary Supervisor, Professor Marianne Elliott, for her immeasurable support, encouragement and guidance and to Dr Karyn Morrissey, Department of Geography, in her role as Second Supervisor. Her guidance and suggestions with regards to the overall framework and structure of the thesis have been invaluable. Particular thanks also to Dr Patrick Nugent who was my original supervisor. He has remained a friend and mentor and I am eternally grateful to him for the continuing enthusiasm he has shown towards my research. I am grateful to the British Association for Irish Studies who awarded a research scholarship to assist with research expenses. In addition, I would like to thank my Programme Leader at Liverpool John Moores University, Alistair Beere, who provided both research and financial support to ensure the timely completion of my thesis. My special thanks to Rev. Dr Tom Deenihan, Diocesan Secretary, for providing an invaluable letter of introduction in support of my research and to the many staff in parishes across the diocese for their help. I am also indebted to the people of Cork for their help, hospitality and time, all of which was given so freely and willingly. Particular thanks to Joe Creedon of Inchigeelagh and local archaeologist Tony Miller. -

The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers

THE LIST of CHURCH OF IRELAND PARISH REGISTERS A Colour-coded Resource Accounting For What Survives; Where It Is; & With Additional Information of Copies, Transcripts and Online Indexes SEPTEMBER 2021 The List of Parish Registers The List of Church of Ireland Parish Registers was originally compiled in-house for the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI), now the National Archives of Ireland (NAI), by Miss Margaret Griffith (1911-2001) Deputy Keeper of the PROI during the 1950s. Griffith’s original list (which was titled the Table of Parochial Records and Copies) was based on inventories returned by the parochial officers about the year 1875/6, and thereafter corrected in the light of subsequent events - most particularly the tragic destruction of the PROI in 1922 when over 500 collections were destroyed. A table showing the position before 1922 had been published in July 1891 as an appendix to the 23rd Report of the Deputy Keeper of the Public Records Office of Ireland. In the light of the 1922 fire, the list changed dramatically – the large numbers of collections underlined indicated that they had been destroyed by fire in 1922. The List has been updated regularly since 1984, when PROI agreed that the RCB Library should be the place of deposit for Church of Ireland registers. Under the tenure of Dr Raymond Refaussé, the Church’s first professional archivist, the work of gathering in registers and other local records from local custody was carried out in earnest and today the RCB Library’s parish collections number 1,114. The Library is also responsible for the care of registers that remain in local custody, although until they are transferred it is difficult to ascertain exactly what dates are covered.