Download the Archive Issue 19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baldwins of Lisnagat : Work in Progress

The Baldwins of Lisnagat : Work in Progress Alexandra Buhagiar 2014 CONTENTS Tables and Pictures Preamble INTRODUCTION Presentation of material Notes on material Abbreviations Terms used Useful sources of information CHAPTER 1 Brief historical introduction: 1600s to mid-1850s ‘The Protestant Ascendancy’ The early Baldwin estates: Curravordy (Mount Pleasant) Lisnagat Clohina Lissarda CHAPTER 2 Generation 5 (i.e. most recent) Mary Milner Baldwin (married name McCreight) Birth, marriage Children Brief background to the McCreight family William McCreight Birth, marriage, death Education Residence Civic involvement CHAPTER 3 Generation 1 (i.e. most distant) Banfield family Brief background to the Banfields Immediate ancestors of Francis Banfield (Gen 1) Francis Banfield (Gen 1) Birth, marriage, residence etc His Will Children (see also Gen 2) The father of Francis Banfield Property Early Milners CHAPTER 4 Generation 2 William Milner His wife, Sarah Banfield Their children, Mary, Elizabeth and Sarah (Gen. 3. See also Chapter 5) CHAPTER 5 Generation 3 William Baldwin Birth, marriage, residence etc Children: Elizabeth, Sarah, Corliss, Henry and James (Gen. 4. See also Chapter 6) Property His wife, Mary Milner Her sisters : Elizabeth Milner (married to James Barry) Sarah Milner CHAPTER 6 Generation 4 The children of William Baldwin and Mary Milner: Elizabeth Baldwin (married firstly Dr. Henry James Wilson and then Edward Herrick) Sarah Baldwin (married name: McCarthy) Corliss William Baldwin Confusion over correct spouse Property Other Corliss Baldwins in County Cork Henry Baldwin James Baldwin Birth, marriage, residence etc. Property His wife, Frances Baldwin CHAPTER 7 Compilation of tree CHAPTER 8 Confusion of William Baldwin's family with that of 'John Baldwin, Mayor of Cork' Corliss Baldwin (Gen 4) Elizabeth Baldwin (Gen 4) CHAPTER 9 The relationship between ‘my’ William Baldwin and the well documented ‘John Baldwin, Mayor of Cork’ family CHAPTER 10 Possible link to another Baldwin family APPENDIX 1. -

An Investigation of Vegetation and Environmental Change in the Comeragh Mountains

An investigation of vegetation and environmental change in the Comeragh Mountains Dr Bettina Stefanini An investigation of vegetation and environmental change in the Comeragh Mountains Prepared by Dr Bettina Stefanini 8 Middle Mountjoy Street Phibsboro Dublin 7 Phone: 087 218 0048 email: [email protected] February 2013 2 Introduction Ireland has a dense network of over 475 palaeoecological records of Quaternary origin. However, there are few late-Holocene vegetation records from Waterford and the extant ones are truncated (Mitchell et al. 2013). Thus the county presents a blank canvas regarding prehistoric vegetation dynamics. Likewise, possible traces in the environment of its well documented 18th century mining and potential earlier mining history have not been found so far. This study was commissioned by the Metal Links project, at the Copper Coast Geopark, which is part funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) through the Ireland Wales Programme 2007 - 2013 (Interreg 4A). It aims to investigate vegetation dynamics, mining history and environmental change in the Comeragh Mountains. Site description and sampling Ombrotrophic peat is the most promising medium for geochemical analysis since metal traces are thought to be immobile in this matrix (Mighall et al. 2009). Such deposits are equally well suited for microfossil analysis and for this reason the same cores were chosen for both analyses. The selection of potential study sites presented difficulties due to extensive local disturbance of peat sediments. Initial inspection of deposits on the flanks of the Comeragh Mountains revealed that past peat harvesting had removed or disturbed much of this material and thus rendered it unsuitable for analysis. -

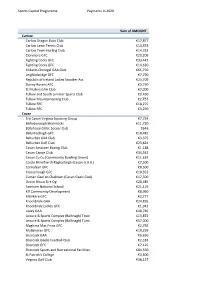

Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Sum of AMOUNT Carlow

Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Sum of AMOUNT Carlow Carlow Dragon Boat Club €17,877 Carlow Lawn Tennis Club €14,353 Carlow Town Hurling Club €14,332 Clonmore GFC €23,209 Fighting Cocks GFC €33,442 Fighting Cocks GFC €14,620 Kildavin Clonegal GAA Club €61,750 Leighlinbridge GFC €7,790 Republic of Ireland Ladies Snooker Ass €23,709 Slaney Rovers AFC €3,750 St Mullins GAA Club €7,000 Tullow and South Leinster Sports Club €9,430 Tullow Mountaineering Club €2,757 Tullow RFC €18,275 Tullow RFC €3,250 Cavan 3rd Cavan Virginia Scouting Group €7,754 Bailieborough Shamrocks €11,720 Ballyhaise Celtic Soccer Club €646 Ballymachugh GFC €10,481 Belturbet GAA Club €3,375 Belturbet Golf Club €23,824 Cavan Amatuer Boxing Club €1,188 Cavan Canoe Club €34,542 Cavan Co Co (Community Bowling Green) €11,624 Coiste Bhreifne Uí Raghaillaigh (Cavan G.A.A.) €7,500 Cornafean GFC €8,500 Crosserlough GFC €10,352 Cuman Gael an Chabhain (Cavan Gaels GAA) €17,500 Droim Dhuin Eire Og €20,485 Farnham National School €21,119 Kill Community Development €8,960 Killinkere GFC €2,777 Knockbride GAA €24,835 Knockbride Ladies GFC €1,942 Lavey GAA €48,785 Leisure & Sports Complex (Ballinagh) Trust €13,872 Leisure & Sports Complex (Ballinagh) Turst €57,000 Maghera Mac Finns GFC €2,792 Mullahoran GFC €10,259 Shercock GAA €6,650 Shercock Gaelic Football Club €2,183 Shercock GFC €7,125 Shercock Sports and Recreational Facilities €84,550 St Patrick's College €3,500 Virginia Golf Club €38,127 Sports Capital Programme Payments in 2020 Virginia Kayak Club €9,633 Cavan Castlerahan -

IRISH LIFE SCIENCES Directory ©Enterprise Ireland December ‘10 - (251R)

The IRISH LIFE SCIENCES Directory ©Enterprise Ireland December ‘10 - (251R) The see map underneathπ IrIsh The LIfe scIences www.enterprise-ireland.com Irish Life Sciences Directory Ireland is a globally recognised centre of excellence in the Life Sciences industry. Directory This directory highlights the opportunities open to international companies to partner and do business with world-class Irish enterprises. Funded by the Irish Government under the National Development Plan, 2007-2013 see map overleaf ∏ Irish Life Sciences Companies Donegal Roscommon Itronik Interconnect Ltd. ANSAmed Moll Industries Ireland Ltd. Wiss Medi Teo. Westmeath Arran Chemical Co Ltd. Leitrim Cavan Univet Ltd. Mayo M&V Medical Devices Ltd. Vistamed Ltd. Louth LLR-G5 Ltd Mergon Healthcare AmRay Medical Ovagen Group Ltd. Technical Engineering Bellurgan Precision Engineering Ltd. Precision Wire Components & Tooling Services Ltd. ID Technology Ltd. Trend Technologies Mullingar Ltd. Millmount Healthcare Ltd. New Era Packaging Ltd. Sligo Ovelle Ltd. Arrotek Medical Ltd. Letterkenny Derry Uniblock Ltd. Avenue Mould Solutions Ltd. Donegal iNBLEX Plastics Ltd Donegal Northern Galway ProTek Medical Ltd. Aerogen Ltd. SL Controls Ltd. Ireland Belfast Longford Anecto Ltd. Socrates Finesse Medical Ltd. APOS TopChem Laboratories Ltd. Avonmed Healthcare Ltd. TopChem Pharmaceutcals Ltd. Bio Medical Research Enniskillen Monaghan Meath BSM Ireland Ltd. Leitrim Newry ArcRoyal Ltd. Cambus Medical Sligo Monaghan Ballina Sligo Kells Stainless Ltd. Cappella Medical Devices Ltd. Cavan Carrick-on-Shannon Novachem Corporation Ltd. Caragh Precision Dundalk Cavan Offaly Chanelle Medical Castlebar Louth Chanelle Pharamaceuticals Europharma Concepts Ltd. Mayo Roscommon Manufacturing Ltd. Westport Longford Drogheda Midland Bandages Ltd. Clada Medical Devices Roscommon Steripack Medical Packaging Longford Meath Complete Laboratory Solutions Contech Ireland Dublin Athlone Creagh Medical Limited Mullingar AGI Therapeutics Plc. -

Social Housing Construction Projects Status Report Q3 2019

Social Housing Construction Projects Status Report Q3 2019 December 2019 Rebuilding Ireland - Action Plan for Housing and Homelessness Quarter 3 of 2019: Social Housing Construction Status Report Rebuilding Ireland: Social Housing Targets Under Rebuilding Ireland, the Government has committed more than €6 billion to support the accelerated delivery of over 138,000 additional social housing homes to be delivered by end 2021. This will include 83,760 HAP homes, 3,800 RAS homes and over 50,000 new homes, broken down as follows: Build: 33,617; Acquisition: 6,830; Leasing: 10,036. It should be noted that, in the context of the review of Rebuilding Ireland and the refocussing of the social housing delivery programme to direct build, the number of newly constructed and built homes to be delivered by 2021 has increased significantly with overall delivery increasing from 47,000 new homes to over 50,000. This has also resulted in the rebalancing of delivery under the construction programme from 26,000 to 33,617 with acquisition targets moving from 11,000 to 6,830. It is positive to see in the latest Construction Status Report that 6,499 social homes are currently onsite. The delivery of these homes along with the additional 8,050 homes in the pipeline will substantially aid the continued reduction in the number of households on social housing waiting lists. These numbers continue to decline with a 5% reduction of households on the waiting lists between 2018 and 2019 and a 25% reduction since 2016. This progress has been possible due to the strong delivery under Rebuilding Ireland with 90,011 households supported up to end of Q3 2019 since Rebuilding Ireland in 2016. -

The Tipperary

Walk The Tipperary 10 http://alinkto.me/mjk www.discoverireland.ie/thetipperary10 48 hours in Tipperary This is the Ireland you have been looking for – base yourself in any village or town in County Tipperary, relax with friends (and the locals) and take in all of Tipperary’s natural beauty. Make the iconic Rock of Cashel your first stop, then choose between castles and forest trails, moun- tain rambles or a pub lunch alongside lazy rivers. For ideas and Special Offers visit www.discoverireland.ie/thetipperary10 Walk The Tipperary 10 Challenge We challenge you to walk all of The Tipperary 10 (you can take as long as you like)! Guided Walks Every one of The Tipperary 10 will host an event with a guide and an invitation to join us for refreshments afterwards. Visit us on-line to find out these dates for your diary. For details contact John at 087 0556465. Accommodation Choose from B&Bs, Guest Houses, Hotels, Self-Catering, Youth Hostels & Camp Sites. No matter what kind of accommodation you’re after, we have just the place for you to stay while you explore our beautiful county. Visit us on line to choose and book your favourite location. Golden to the Rock of Cashel Rock of Cashel 1 Photo: Rock of Cashel by Brendan Fennssey Walk Information 1 Golden to the Rock of Cashel Distance of walk: 10km Walk Type: Linear walk Time: 2 - 2.5 hours Level of walk: Easy Start: At the Bridge in Golden Trail End (Grid: S 075 409 OS map no. 66) Cashel Finish: At the Rock of Cashel (Grid: S 012 384 OS map no. -

Irish Successes on K2 Patagonia First Ascent

Autumn 2018 €3.95 UK£3.40 ISSN 0790 8008 Issue 127 Irish successes on K2 Two summit ten years after first Irish ascent Patagonia first ascent All-female team climbs Avellano Tower www.mountaineering.ie Photo: Chris Hill (Tourism Ireland) Chris Hill (Tourism Photo: 2 Irish Mountain Log Autumn 2018 A word from the edItor ISSUE 127 The Irish Mountain Log is the membership magazine of Mountaineering Ireland. The organisation promotes the interests of hillwalkers and climbers in Ireland. Mountaineering Ireland Welcome Mountaineering Ireland Ltd is a company limited by guarantee and elcome! Autumn is here registered in Dublin, No 199053. Registered office: Irish Sport HQ, with a bang. There is a National Sports Campus, nip in the air and the Blanchardstown, Dublin 15, Ireland. leaves on the trees are Tel: (+353 1) 625 1115 assuming that wonderful In the Greater ranges and in the Fax: (+353 1) 625 1116 [email protected] golden-brownW hue. Alps, the effects of climate ❝ www.mountaineering.ie This has been an exciting year so far for change are very evident. Irish mountaineers climbing in the Greater Hot Rock Climbing Wall Ranges (see our report, page 20). In Nepal, In the Greater Ranges and in the Alps, the Tollymore Mountain Centre there were two more Irish ascents of Bryansford, Newcastle effects of climate change are very evident. County Down, BT33 0PT Everest, bringing the total to fifty-nine Climate change is no longer a theoretical Tel: (+44 28) 4372 5354 since the first ascent, twenty-five years possibility, it is happening. As mountaineers, [email protected] ago, by Dawson Stelfox in 1993. -

Irish Landscape Names

Irish Landscape Names Preface to 2010 edition Stradbally on its own denotes a parish and village); there is usually no equivalent word in the Irish form, such as sliabh or cnoc; and the Ordnance The following document is extracted from the database used to prepare the list Survey forms have not gained currency locally or amongst hill-walkers. The of peaks included on the „Summits‟ section and other sections at second group of exceptions concerns hills for which there was substantial www.mountainviews.ie The document comprises the name data and key evidence from alternative authoritative sources for a name other than the one geographical data for each peak listed on the website as of May 2010, with shown on OS maps, e.g. Croaghonagh / Cruach Eoghanach in Co. Donegal, some minor changes and omissions. The geographical data on the website is marked on the Discovery map as Barnesmore, or Slievetrue in Co. Antrim, more comprehensive. marked on the Discoverer map as Carn Hill. In some of these cases, the evidence for overriding the map forms comes from other Ordnance Survey The data was collated over a number of years by a team of volunteer sources, such as the Ordnance Survey Memoirs. It should be emphasised that contributors to the website. The list in use started with the 2000ft list of Rev. these exceptions represent only a very small percentage of the names listed Vandeleur (1950s), the 600m list based on this by Joss Lynam (1970s) and the and that the forms used by the Placenames Branch and/or OSI/OSNI are 400 and 500m lists of Michael Dewey and Myrddyn Phillips. -

Cork City and County Archives Index to Listed Collections with Scope and Content

Cork City and County Archives Index to Listed Collections with Scope and Content A State of the Ref. IE CCCA/U73 Date: 1769 Level: item Extent: 32pp Diocese of Cloyne Scope and Content: Photocopy of MS. volume 'A State of The Diocese of Cloyne With Respect to the Several Parishes... Containing The State of the Churches, the Glebes, Patrons, Proxies, Taxations in the King's Books, Crown – Rents, and the Names of the Incumbents, with Other Observations, In Alphabetical Order, Carefully collected from the Visitation Books and other Records preserved in the Registry of that See'. Gives ecclesiastical details of the parishes of Cloyne; lists the state of each parish and outlines the duties of the Dean. (Copy of PRONI T2862/5) Account Book of Ref. IE CCCA/SM667 Date: c.1865 - 1875 Level: fonds Extent: 150pp Richard Lee Scope and Content: Account ledger of Richard Lee, Architect and Builder, 7 North Street, Skibbereen. Included are clients’ names, and entries for materials, labourers’ wages, and fees. Pages 78 to 117 have been torn out. Clients include the Munster Bank, Provincial Bank, F McCarthy Brewery, Skibbereen Town Commissioners, Skibbereen Board of Guardians, Schull Board of Guardians, George Vickery, Banduff Quarry, Rev MFS Townsend of Castletownsend, Mrs Townsend of Caheragh, Richard Beamish, Captain A Morgan, Abbeystrewry Church, Beecher Arms Hotel, and others. One client account is called ‘Masonic Hall’ (pp30-31) [Lee was a member of Masonic Lodge no.15 and was responsible for the building of the lodge room]. On page 31 is written a note regarding the New Testament. Account Book of Ref. -

This Includes Galway, Roscommon

CHO 2 - Service Provider Resumption of Adult Day Services Portal For further information please contact your service provider directly. Last updated 2/03/21 Location Service Provider Organisation Day Service Location Name Address Area Telephone Number Email Address Id ABILITY WEST 2720 ACTIVE AGING 185 Tirellan Heights, Headford Rd GALWAY [email protected] ABILITY WEST 702 BEECHWOOD ADS Snipe Avenue, Newcastle GALWAY 091 528122 [email protected] ABILITY WEST 2718 BLACKROCK HOUSE Salthill GALWAY 091 522323 [email protected] ABILITY WEST 691 BROOKLODGE SERVICE The Old Monastery, Ballyglunin GALWAY 091 528122 [email protected] ABILITY WEST 700 CHRIOST LINN A.D.S. Carriage House Way, Railway Station, Clifden GALWAY 09521057 [email protected] ABILITY WEST 2719 COIS NA COILLE Liosban Industrial Estate GALWAY 091 756635 [email protected] ABILITY WEST 3108 DOCHAS ADS Mountkelly, Glenamaddy GALWAY 099 659088 [email protected] ABILITY WEST 3109 MEITHEAL SERVICE Commerce House, Moycullen GALWAY 091 705647 [email protected] ABILITY WEST 703 MILAOISE ADS Weir Rd, Tuam, Tuam GALWAY 093 70512 [email protected] ABILITY WEST 2294 MOUNTBELLEW RESOURCE CENTRE Bovinion, Mountbellew GALWAY 090 9623751 [email protected] ABILITY WEST 2747 NEW DIRECTIONS HEADFORD Unit 1 Inchiquinn House, Main St Headford GALWAY 093 28707 judith.wall@abiltiy west.ie ABILITY WEST 2926 NEW DIRECTIONS TUAM Galway Rd, Tuam GALWAY 093 34472 [email protected] ABILITY -

List of Irish Mountain Passes

List of Irish Mountain Passes The following document is a list of mountain passes and similar features extracted from the gazetteer, Irish Landscape Names. Please consult the full document (also available at Mountain Views) for the abbreviations of sources, symbols and conventions adopted. The list was compiled during the month of June 2020 and comprises more than eighty Irish passes and cols, including both vehicular passes and pedestrian saddles. There were thousands of features that could have been included, but since I intended this as part of a gazetteer of place-names in the Irish mountain landscape, I had to be selective and decided to focus on those which have names and are of importance to walkers, either as a starting point for a route or as a way of accessing summits. Some heights are approximate due to the lack of a spot height on maps. Certain features have not been categorised as passes, such as Barnesmore Gap, Doo Lough Pass and Ballaghaneary because they did not fulfil geographical criteria for various reasons which are explained under the entry for the individual feature. They have, however, been included in the list as important features in the mountain landscape. Paul Tempan, July 2020 Anglicised Name Irish Name Irish Name, Source and Notes on Feature and Place-Name Range / County Grid Ref. Heig OSI Meaning Region ht Disco very Map Sheet Ballaghbeama Bealach Béime Ir. Bealach Béime Ballaghbeama is one of Ireland’s wildest passes. It is Dunkerron Kerry V754 781 260 78 (pass, motor) [logainm.ie], ‘pass of the extremely steep on both sides, with barely any level Mountains ground to park a car at the summit. -

Survey to Locate Mountain Blanket Bogs in Ireland

SURVEY TO LOCATE MOUNTAIN BLANKET BOGS OF SCIENTIFIC INTEREST IN IRELAND Dr Enda Mooney Roger Goodwillie Caitriona Douglas Commissioned by National Parks and Wildlife Service, OPW 1991 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 METHODS 3 Site Evaluation 4 RESULTS: General Observations 6 High Blanket Bog 8 Flushed Slopes 9 Headwater Bog 9 Mountain Valley Bog 10 High Level Montane Blanket Bog 10 Low Level Montane Blanket Bog 12 SITES OF HIGH CONSERVATION VALUE SITE NAME COUNTY PAGE NO Cullenagh Tipperary 17 Crockastoller Donegal 19 Coomacheo Cork 24 Meenawannia Donegal 28 Malinbeg Donegal 31 Altan Donegal 34 Meentygrannagh Donegal 36 Lettercraffroe Galway 40 Tullytresna Donegal 45 Caherbarnagh Cork 47 Glenkeen Laois 51 Ballynalug Laois 54 Kippure Wicklow 57 Doobin Donegal 61 Meenachullion Donegal 63 Sallygap Wicklow 65 Knockastumpa Kerry 68 Derryclogher Cork 71 Glenlough. Cork 73 Coumanare Kerry 75 SITES OF MODERATE-HIGH CONSERVATION VALUE Ballard Donegal 78 Cloghervaddy Donegal 80 Crowdoo Donegal 83 Meenaguse Scragh Donegal 86 Glanmore Cork 88 Maulagowna Kerry 90 Sillahertane Kerry 91 Carrig East Kerry 95 Mangerton Kerry 97 Drumnasharragh Donegal 99 Derryduff More or Derrybeg Cork 100 Ballagh Bog (K25) Kerry 103 Dereen Upper Cork 105 Comeragh Mts. Waterford 107 Tullynaclaggan Donegal 109 Tooreenbreanla Kerry 111 Glendine West Offaly 114 Coomagire Kerry 116 Graignagower Kerry 118 Tooreenealagh Kerry 119 Ballynabrocky Dublin 121 Castle Kelly Dublin 125 Shankill Wicklow 126 Garranbaun Laois 128 Cashel Donegal 130 Table Mt Wicklow 132 Ballynultagh Wicklow 135