Study on Wild Fire Fighting Resources Sharing Models Final Report October 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning for the Future

Planning for the Future The Yellowknife Airport (YZF) Development Plan Summary For more information contact: Airport Manager #1, Yellowknife Airport Yellowknife, NT X1A 3T2 Phone: (867) 873-4680 Fax: (867) 873-3313 Email: [email protected] Or Regional Superintendent, North Slave Region GNWT - Department of Transportation PO Box 1320 Yellowknife, NT X1A 2L9 Phone: (867) 920-3096 Fax: (867) 873-0606 Email: [email protected] Government of the Northwest Territories Department of Transportation The Yellowknife Airport (YZF) Development Plan was prepared for the Government of the Northwest Territories by InterVISTAS Consulting Inc., Earth Tech (Canada) Inc. and PDK Airport Planning Inc. November 2004 Introduction Looking Towards the Future Transportation plays a critical role as a driver of Northern Canada’s economy. The Government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT), working together with the City of Yellowknife, is charting the course for future development at the Yellowknife Airport, with emphasis on safety, security and efficiency. Airport development must also be reasonable, responsible and affordable. The system must be efficient for the flow of goods and people within the airport, to and from the city and the NWT, as well as across our country and its borders. Yellowknife Airport and the City of Yellowknife have experienced rapid growth over the last ten years as a result of a robust economy. The Yellowknife Airport serves as the primary gateway to and from points outside the Northwest Territories. The City is the Diamond Capital of North America. Aviation passenger growth has exceeded national levels. Air cargo traffic servicing municipal enterprises, area mining and mineral operations and exploration is also at record volumes. -

Building for the North Summit Aviation Focuses on Evolution and Partnerships WHEN DEPENDABLE MEANS EVERYTHING

AN mHm PUbLISHING mAGAZINe November/December 2016 [ INSIDE ] • INDUSTRY NEWS • H1 HELIPORT HEADACHE • INNOTECH AVIATION PROFILE • LEAR 75 FLIGHT TEST skiesmag.com • LHM-1 HYBRID AIRSHIP AvIAtIoN IS oUr PassioN BUILDING FOR THE NORTH SUMMIT AVIATION FOCUSES ON EVOLUTION AND PARTNERSHIPS WHEN DEPENDABLE MEANS EVERYTHING Each mission is unique, but all P&WC turboshaft engines have one thing in common: You can depend on them. Designed for outstanding performance, enhanced fl ying experience and competitive operating economics, the PW200 and PT6 engine families are the leaders in helicopter power. With innovative technology that respects the environment and a trusted support network that offers you peace of mind, you can focus on what matters most: A MISSION ACCOMPLISHED WWW.PWC.CA POWERFUL. EFFICIENT. VERSATILE. SOUND LIKE ANYBODY YOU KNOW? You demand continuous improvement in your business, so why not expect it from your business aircraft? Through intelligent design the new PC-12 NG climbs faster, cruises faster, and is even more quiet, comfortable and efficient than its predecessor. If your current aircraft isn’t giving you this kind of value, maybe it’s time for a Pilatus. Stan Kuliavas, Vice President of Sales | [email protected] | 1 844.538.2376 | www.levaero.com November/December 2016 1 Levaero-Full-CSV6I6.indd 1 2016-09-29 1:12 PM November/December 2016 Volume 6, Issue 6 in this issue in the JUmpseat. 06 view from the hill ......08 focal Points ........... 10 Briefing room .......... 12 plane spotting .........30 APS: Upset Training -

De Havilland Canada Cc-108/ C-7 Caribou

Last updated 1 July 2021 ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| DE HAVILLAND CANADA CC-108/ C-7 CARIBOU ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| 1 DHC-4 CF-KTK-X De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Ltd, Downsview: ff 30.7.58 Mk.1 (to RCAF as 5303): BOC 22.7.60 T64 turbines De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Ltd: loan .61/64 testflown with GE T64 turbines, ff 22.9.61 Mk.1A (returned to RCAF as 5303): redel. 17.6.64 (to Tanzanian AF as JW9011): del. ex Trenton 15.6.71 5H-AAC John Woods Inc, Dallas TX 79 N1016N John Woods Inc, Dallas TX: USCR 3.79/02 (stored at Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania 92/99) rep: Interocean Airways, Beira, Mozambique 92 scrapped: struck-off USCR 5.7.02 _______________________________________________________________________________________ 2 • DHC-4 CF-LAN-X De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Ltd, Downsview ONT .59 DHC-4A CF-LAN De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Ltd: demonstrator 61/66 N6080 Imperial Oil 8.5.66/70 Intermountain Aviation, Marana AZ: del. 15.6.71/75 (used on USFS contracts for smoke jumpers) Tynol Associates Inc/ Air America, Marana AZ 21.1.75 Omni Aircraft Sales, Washington DC 2.2.76/77 Environment Research Institute of Michigan, Detroit-Willow Run MI 16.6.77/98 H A T Aviation, Detroit-Willow Run MI 27.8.98/09 Yankee Air Museum, Willow Run MI 6.09/20 (displ. painted as “US Army 62-4171”) N6080 John K. Bagley, Rexburg ID 8.3.21 _______________________________________________________________________________________ 3 YAC-1 CF-LKI-X De Havilland Aircraft of Canada Ltd, Downsview ONT .59 (to US Army as 57-3079 but not del.) crashed during pre-del. -

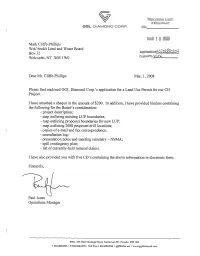

GGL DIAMOND CORP. Mark Ciiffe-Phillips Wek'eezhii Land And

GGL DIAMOND CORP. Mark CIiffe-Phillips Wek'eezhii Land and Water Board Box 32 Wekweeti, NT XOE 1 WO Dear Mr. Cliffe-Phillips Mar. 1, 2008 Please find enclosed GGL Diamond Corp.'s application for a Land Use Permit for our CH Project. I have attached a cheque in the amount of $200. In addition, I have provided binders containing the following for the Board's consideration: - project description; - map outlining existing LUP boundaries; - map outlining proposed boundaries for new LUP; - map outlining 2008 proposed drill locations; - copies of e-mail and fax correspondence; - consultation log; - presentation notes and meeting summary — NSMA; - spill contingency plan; - list of currently-held mineral claims. I have also provided you with five CD's containing the above information in electronic form. Sincerely, Paul Jones Operations Manager V904 - 675 West Hastings Street, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6B IN2 1604.688.0546 f F 604.688.0378 1 Toll Free 1.866.688.0546 I [email protected] I www.ggldia,nond.carn 1`. Box 32, Wekweeti, NT XOE I WO Land and Water Board Tel: 867-713-2500 • Fax: 867-713-2502 - www.wlwb.ca Application for: New Land Use Permit q Amendment q to I. Applicant's name and mailing address: Fax number: (604) 688-0378 GGL Diamond Corp. 6005 Finlayson Dr. N Telephone number: (867) 873-3025 YELLOWKNIFE, NT XIA 3L1 2. Head office address: Fax number: (604) 688-0378 #904-675 W. Hastings St. VANCOUVER, BC V6B IN2 Field supervisor: Paul Jones Radiotelephone: (604) 628-9894 Telephone number: (604) 688-0546 3. Other personnel (subcontractor, contractors, company staff etc.) Great Slave Helicopters; Major Midwest Drilling; Aurora Geosciences Ltd.; Air Tindi Ltd.; Arctic Sunwest Charters; various GGL staff TOTAL: (Number of persons on site) — varies, but a maximum of 15 4. -

Yellowknife Heritage Building Project

Yellowknife Heritage Building Project City of Yellowknife Heritage Committee Compiled by Ryan Silke Updated September 2018 by R.S. Yellowknife Heritage Building Project Part A – Yellowknife area McMeekanO Cabin MAP ID: A-1 DESIGNATION: ADDRESS: Fred Henne Territorial Park CURRENT OWNER: GNWT Industry, Tourism and Investment OCCUPANT: None CURRENT USE: None BUILT: 1939 CONSTRUCTION: . Log cabin DESCRIPTIVE HISTORY: This cabin was built by prospectors Jim Turner and Morris Evans in 1939 from logs that were cut and floated down the Yellowknife River, and erected on the east side of Latham Island. This land was unsurveyed in the 1940s-1950s (adjacent to Lot 26, Block 153), but later became Lot 5, Block 202, located near the public boat launch just off Otto Drive (Turner Point). Jock McMeekan acquired the cabin, possibly from George Blyler, and it was from here that he and his wife Mildred (Hall) McMeekan produced The Yellowknife Blade newspaper which began in October 1940. McMeekan lived in Yellowknife and wrote the newspaper sporadically until he left for Uranium City, Saskatchewan in 1953. Bill Louitit was the owner of the cabin from 1965 to the 1980s. Beatrice & Pat Woods were living here in the 1970s. Susan Cross was the owner of the cabin in the early 1990s. Plans were made to redevelop the lot and remove the log cabin, which required significant work to make it livable again. The City of Yellowknife Heritage Committee took the lead to find it a new home, and a call went out to anybody with an interest or a plan for relocating and restoring the old log cabin. -

NWT & Nunavut Chamber of Mines Members Directory 2012

NWT & NUNAVUT CHAMBER OF MINES NWT NWT & NUNAVUTNUNAVUT CHAMBER OF MINES 2012 MEMBERS SERVICE DIRECTORY NWT & NUNAVUT CHAMBER OF MINES NWT & NUNAVUT CHAMBER OF MINES 2011-12 BOARD OF DIRECTORS E: [email protected] 703-5201 50 Ave Yellowknife, NT X1A 3S9 BFR Copper & Gold Inc. W: www.bullmoosemines.com Cansel Survey Equipment PRESIDENT Brent Murphy, Seabridge Gold Inc. ● Consulting/Service/Supply Contact: Michele Guy 510 Chotem Cres Saskatoon, SK S7N 4M4 E: [email protected] 3751 Napier St Burnaby, BC V5C 3E4 ▲ Pamela Strand, Shear Diamonds Ltd. 400-106 Front St. E Toronto, ON M5A 1E3 ALS Environmental P: 867-920-4074 F: 604-291-6163 Contact: Dawn Zhou Exploration Contact: Pamela Shyng 202-6 Adelaide St. E, Toronto, ON M5C 1H6 T: 867-445-5553 F: 416-367-2711 A W: www.ae.ca P: 306-933-4261 F: 888-334-6418 P: 604-299-5794 F: 604-299-5701 9936 67 Ave Edmonton AB T6E 0P5 T: 416-479-8728 ext. 226 F: 416-703-1903 [email protected] E: [email protected] A & A Technical Services Contact: Sean Johnston E: [email protected] W: www.cansel.ca [email protected] PO Box 2922 Yellowknife, NT X1A 2R2 ● Consulting/Service/Supply ▲ Exploration E: [email protected] Chuck Parker, Discovery Air P: 780-413-5227 F: 780-437-2311 Contact: Al Harman ● Consulting/Service/Supply VICE-PRESIDENT NWT PO Box 1693 Yellowknife, NT X1A 2P3 W: www.alsglobal.com Association for Mineral Exploration BC BHP Billiton Canada Inc. P: 867-669-7022 F: 867-669-7077 Cathie Bolstad, De Beers Canada Inc. -

BARS Program Update April 2012 Newsletter

Program Update Issue 3 April 2012 BARS Managing Director Inside this issue: Update The first quarter of this year has ARM3 and TAC7 2 certainly been a busy period for the BARS Program. Whilst a number of new audits have been conducted, we have The 2012 Calendar— 2 also seen a number of recurrent audits Upcoming Events Greg Marshall presenting at Aeromed Africa Conference. undertaken. operators within this sector who also provide We have released version 4 of the BAR Standard services to the mining industry. Auditor Accreditation 2 that incorporates provisions for Aero-medical Course, Melbourne operations, principally in support of the resource Finally, I visited Yellowknife in the far north of sector, and for the use of night vision goggles. To Canada and met with some of the operators coincide with the release of the new Standard, a there who have undergone a BARS audit. It was The Current List of 3 new checklist has also been uploaded. The new particularly enlightening to understand some of Aircraft Operators Standard can be found on the Foundation’s the challenges that they face in such a remote who have undergone website at www.flightsafety.orgbbarsbbar- and cold climate. My thanks to those operators BARS Audit standard. for their hospitality at short notice. I will provide some further insight into remote operations from Current BARS Statistics 4 During March and April we were able to deliver this location in the next edition. presentations on the BAR Standard Program and Following on from these visits we anticipate Aviation Coordinator training at a number of running some AVCO courses in both Vancouver conferences. -

Contract Detail by Designated Local Community

Report Group: Private - Private Report Number: CR10C-07 Deliver To: BIP Monitoring Office Report Title: Contracts over $5,000 - Contract Detail by Designated Local Community Report Type: OD-CR10A - Basic Contract Report This type of report prints data about contracts issued pursuant to a procurement entered into the system. It selects base data that meets the following conditions: - A valid procurement exists. - At least one valid bid (including a valid Business) is on file. - An award has been made to a valid bid. - At least one contract has been issued to a valid bidder. The base data for each contract and all associated amendments is summarized into a single report line. Some reports summarize further, but the unique contract number is the lowest level of detail with this type of report. The fiscal period for contracts on this report is determined by the start date entered for the contract or any amendments. Only amounts specified on a document with a start date in the fiscal year of the report are actually reported. Report period: Y Current year information only selected Filter on: Less Than 5000 N Sorted on: Designated Local Co(Print headings and footings) Department/Agency (No headings or footings) Business Name (No headings or footings) Skip to new page at: Designated Local Community Items reported: Department/Agency Procurement Number Procurement Designation Procurement Process Business Name Business Location Business Status Contract Document Contract Amount Report Type: OD-CR10A GNWT Contract Registry and Reporting System -

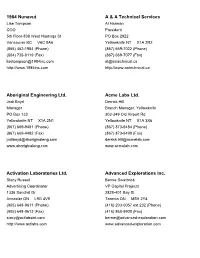

1984 Nunavut a & a Technical Services Aboriginal Engineering

1984 Nunavut A & A Technical Services Lise Tompson Al Harman COO President 5th Floor-838 West Hastings St PO Box 2922 Vancouver BC V6C 0A6 Yellowknife NT X1A 2R2 (866) 462-1984 (Phone) (867) 669-7022 (Phone) (604) 736-8119 (Fax) (867) 669-7077 (Fax) [email protected] [email protected] http://www.1984inc.com http://www.aatechnical.ca Aboriginal Engineering Ltd. Acme Labs Ltd. Jodi Boyd Derrick Hill Manager Branch Manager, Yellowknife PO Box 133 303-349 Old Airport Rd Yellowknife NT X1A 2N1 Yellowknife NT X1A 3X6 (867) 669-9481 (Phone) (867) 873-9484 (Phone) (867) 669-9482 (Fax) (867) 873-9490 (Fax) [email protected] [email protected] www.aboriginaleng.com www.acmelab.com Activation Laboratories Ltd. Advanced Explorations Inc. Stacy Russell Bernie Swarbrick Advertising Coordinator VP Capital Projects 1336 Sandhill Dr 2828-401 Bay St Ancaster ON L9G 4V5 Toronto ON M5H 2Y4 (905) 648-9611 (Phone) (416) 203-0057 ext 232 (Phone) (905) 648-9613 (Fax) (416) 860-9900 (Fax) [email protected] [email protected] http://www.actlabs.com www.advanced-exploration.com Advanced Medical Solutions Inc. AGI-Envirotank Garth Hupper Justin Wappel Directores Business Operations & Development Division Manager PO Box 911 Box 879 Yellowknife NT X1A 2N7 Biggar SK S0K 0M0 (867) 669-9111 (Phone) (306) 948-5262 (Phone) (867) 669-9112 (Fax) (306) 948-5263 (Fax) [email protected] [email protected] www.advancedmedic.com http://www.envirotank.com Agnico-Eagle Mines Limited Air Tindi Ltd. Larry Connell Paul Henry Corporate Director, Sustainable Development CFO 400-145 King St E PO Box 1693 Toronto ON M5C 2Y7 Yellowknife NT X1A 2P3 (416) 947-1212 (Phone) (867) 669-8200 (Phone) (416) 367-4681 (Fax) (867) 669-8210 (Fax) [email protected] [email protected] www.agnico-eagle.com www.airtindi.com Alaska Structures, Inc. -

International Air Travel, Tourism and Freight Opportunity Study Ii

IVC New Document Template i September 2008 International Air Travel, Tourism and Freight Opportunity Study ii Acknowledgements This study was completed by InterVISTAS and Ile Royale Enterprises Limited under contract to the Investment and Economic Analysis Division of Industry, Tourism and Investment (ITI), Government of the Northwest Territories. Support and advice was provided by the Department of Transportation, Government of the Northwest Territories. Funding support was provided by the SINED program of Indian and Northern Affairs, Government of Canada, Yellowknife Office. The completion of this study would not have been possible without the constructive cooperation of all the tourism operators, industry associations, shippers, carriers, community and government representatives who gave substantial time to this project. Development of the NWT air market is critical to our long term development. This study provides an expert review of options for doing this. However, its primary purpose is to elicit northern comment and discussion. If you want to provide your viewpoint, please forward your comments directly to the Department of Industry, Tourism and Investment, or the Department of Transportation, Government of the Northwest Territories. The primary email address is [email protected], or fax 867-873-0434. InterVISTAS and Ile Royal Enterprises Limited acknowledge the information and support provided by stakeholders described in Appendix 1. September 2008 International Air Travel, Tourism and Freight Opportunity Study iii Table of -

Aviation Investigation Report A07w0003 Loss of Control

AVIATION INVESTIGATION REPORT A07W0003 LOSS OF CONTROL – MARGINAL WEATHER ARCTIC SUNWEST CHARTERS CESSNA A185F C-GSDJ YELLOWKNIFE, NORTHWEST TERRITORIES, 53 nm SE 03 JANUARY 2007 The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. Aviation Investigation Report Loss of Control – Marginal Weather Arctic Sunwest Charters Cessna A185F C-GSDJ Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, 53 nm SE 03 January 2007 Report Number A07W0003 Summary The Cessna A185F (registration C-GSDJ, serial number 18504212) operated by Arctic Sunwest Charters departed Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, at 1019 mountain standard time, with a pilot and three passengers on board, for a round trip flight to Blatchford Lake Lodge, approximately 53 nautical miles southeast. The aircraft was on a company flight itinerary with an estimated time of arrival of 1100. When there was no contact from the pilot by 1300, a communication search and track crawl was conducted by company aircraft, but this was unsuccessful in locating the aircraft. No emergency locator transmitter signal was detected at any time. At 1513, the company reported the aircraft overdue to the Flight Service Station. An active search by the Rescue Coordination Centre was conducted using a number of aircraft. The wreckage of the aircraft was found at 1215, 04 January 2007, on the ice at Blatchford Lake. The pilot and two passengers had sustained fatal injuries, one passenger had sustained serious injuries, and the aircraft was substantially damaged. Ce rapport est également disponible en françcais. -

FORT Mcmurray AIRPORT AUTHORITY ANNUAL REPORT 2014

DISCOVERFORT McMURRAY AIRPORT AUTHORITY ANNUAL REPORT 2014 DISCOVER WHAT’S INSIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from the Board Chair and President & CEO ...................................5 Passengers ...............................................................................................................11 Business ....................................................................................................................21 People .......................................................................................................................27 Community ..............................................................................................................31 Governance and Accountability & Board of Directors ...................................38 Management Discussion & Analysis ...................................................................41 Financial Statements .............................................................................................49 Mission We are responsible stewards of our airports, achieving superior performance in the conduct of safe, secure, effective and efficient operations. Our airport businesses contribute significantly to the economy of the Region, Alberta and Canada. Corporate Values » Excellence in Safety, Security and Environment Performance » Commercially Focused, Fiscally Responsible We are Canada’s Business Sustainability Premier Regional » Exemplary Customer Experience » Leadership Airport » Teamwork Key Success Drivers 1. To optimize the customer experience by leading