Can We Build a Better Women's Prison?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bailey Warren Senior Honors Thesis Project.Pdf

1 Foreword “Dimitri Mitropoulos was asked if he could explain the extraordinary effect his conducting had on orchestra and audience alike, and he answered that he wouldn’t even try to explain it, for fear that he might become like the centipede who was asked by a humble little bug which of his hundred legs moved first when he walked. The centipede, responding to the admiration with immense pride, began to analyze the question, and has not walked since.” This excerpt is from Madeleine L’Engle’s book A Circle of Quiet. In the same chapter as this quote, she explains how when Beethoven performed his sonatas and was immediately asked what his sonatas meant, he simply sat down and played them once more. What L’Engle is trying to get at is if one could truly explain their art, there would have been no reason to create the art in the first place. In response to Mitropoulos’ quote she says, “we’re apt to get tangled up in legs when we begin to analyze the creative process.” Throughout the process of creating this album I have embedded a lot of myself into the project. So much of it has become inherently who I am that I feel as if I have become too close to it. This is the first creative project that I have ever completed to this caliber, and the first collection of musical works that is thoroughly mine. Putting it into words doesn’t seem to do it justice. Analysis can only do so much in describing the nuances of art. -

ICN1886-04-08.Pdf

mm jai:ilia''qiii^ sbbviiigVflraternlty,f' Is alwaya welooine ,to Dry Oooils.—Bnrnham & Company. Legal. Two WMk)B (h>m '.to-day Preatdent Mrs. Race Is very slok. iKDBR OP PUBLICATION.-8TATK OP WlUetta of the Agricultural college A. D. Bnirdsley's father la visiting _ MlohlaaMichiganu, ..In. th.u Circuit Court for tho Thursdnjr, April 1, W hlriri. County of Initham-Iiam-IIIi CliancoryCliancory,. will addriesis the ol lib on "Moslems Mrs. A. O. Walker of Detroit Is Lillian Oamblo, Complainant,'Complainant,)) &nd Mormons." As this will probably VB, Fanners* Club. ipuoh better. Kll Oamblo, Dofondant. be the laafr regular meeting for.some It satlaraclorily appearing to thin court by Miss Luclna Beardsley was home affidavit on fllo that tlio dcfondant, £11 aambto, . dtUB BooMB, March 27, ISSis. weeks thiere will be a large attendance. over Sunday. ia not > roaldent of this atato, hut retidoa at the • The oluti^^^^^^^ full up UKlay. Ladles eapeoially Invited. village or Nunda,iu thoHtatool Now York, on. .1 Chas. McKuigbt Is going to Holly moUon of K. D, Lewia, compltlnant'a aollcltor. Nothlhpnew In inarket.reporta. Quite L. H. Ivjiss, Secretary. for treatment. It la ordered that tho aald dulCndant, £11 Gamble, Claude and Etta West have returned Display of Spring Novelties excels that of any cause hla appoaranco to bo entorod horcln wltbln a quantity of seeds graced the tables four montha from tho data of thla order, and in For neuralgia, rbeumatism,'lumbago, from their visit at Manistee. and the meeting was one of much li> previous season, in point of elegance and var caao of hla appoaranco that ho cauae his anawer gout,' Bwellinga, burns, wounds, etc., There will be a mum social at Mrs. -

SONG ARTIST 375 Roar

# SONG ARTIST 400 We're All In This Together Ben Lee 399 Be The One Dua Lipa 398 Take My Breath Away Berlin 397 Treat You Better Shawn Mendes 396 The Fighter Keith Urban Feat Carrie Underwood 395 I'm Still On You're Side Jimmy Barnes 394 Dance Monkey Tones & I 393 Just Like Fire Pink 392 One Dance Drake Feat Wizkid & Kyla 391 Fire & The Flood Vance Joy 390 Hide Away Daya 389 Don't Wanna Know Maroon 5 Feat Kendrick Lamar 388 Stonger Kanye 387 Dancin with myself Billy Idol 386 London Calling Clash 385 Ain't Nobody (Loves Me Better) Felix Jaehn Feat Jasmine Thompson 384 10,000 Hours Dan + Shay & Justin Bieber 383 You Don’t Know Me Jax Jones Feat RAYE 382 You Need To Calm Down Taylor Swift 381 American Woman Lenny Kravitz 380 You Keep Me Hangin On Kim Wilde 379 Senorita Shawn Mendes & Camila Cabello 378 Whenever, Wherever Shakira 377 The Middle Zedd Feat Maren Morris & Grey 376 Get Lucky Daft Punk Feat Pharrell Williams 375 Roar Katy Perry 374 Heroes David Bowie 373 Hey Ya! Outkast 372 Left Outside Alone Anastasia 371 24K Magic Bruno Mars 370 In My Blood The Veronicas 369 Addicted To You Avicii 368 Welcome to the Jungle Guns N Roses 367 Scars To Your Beautiful Alessia Cara 366 Que Sera Justice Crew 365 I Love You Always Forever Betty Who 364 Strip That Down Liam Payne Feat Quavo 363 Starboy The Weeknd Feat Daft Punk 362 Issues Julia Michaels 361 Rather Be Clean Bandit Feat Jess Glynne 360 Your The Voice John Farnham 359 Moves Like Jagger Maroon 5 Feat Christina Aguilera 358 Am I Wrong Nico & Vinz 357 Take Me To Church Hozier 356 Mr Brightside -

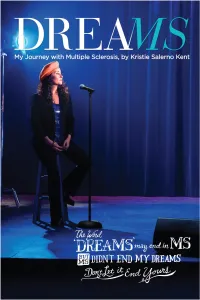

Dreams-041015 1.Pdf

DREAMS My Journey with Multiple Sclerosis By Kristie Salerno Kent DREAMS: MY JOURNEY WITH MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS. Copyright © 2013 by Acorda Therapeutics®, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Author’s Note I always dreamed of a career in the entertainment industry until a multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosis changed my life. Rather than give up on my dream, following my diagnosis I decided to fight back and follow my passion. Songwriting and performance helped me find the strength to face my challenges and help others understand the impact of MS. “Dreams: My Journey with Multiple Sclerosis,” is an intimate and honest story of how, as people living with MS, we can continue to pursue our passion and use it to overcome denial and find the courage to take action to fight MS. It is also a story of how a serious health challenge does not mean you should let go of your plans for the future. The word 'dreams' may end in ‘MS,’ but MS doesn’t have to end your dreams. It has taken an extraordinary team effort to share my story with you. This book is dedicated to my greatest blessings - my children, Kingston and Giabella. You have filled mommy's heart with so much love, pride and joy and have made my ultimate dream come true! To my husband Michael - thank you for being my umbrella during the rainy days until the sun came out again and we could bask in its glow together. Each end of our rainbow has two pots of gold… our precious son and our beautiful daughter! To my heavenly Father, thank you for the gifts you have blessed me with. -

“Together We Can Knock One out of the Park.”

THE Winter 2012 Where Marist Alumni Meet for News “Together we can knock one out of the park.” – Br. Patrick McNamara, fms President, Marist High School Letter From Brother Patrick Winter 2012 reunion&awards 02 Dear Marist Family, Letter From Brother Patrick Marist recently hosted its last Open House for the Class of 2016. More than 03 1,500 students visited the campus this year, and on this last chance before the 2012 Alumni BIG ENTRANCE TEST, I watched a Marist grad giving his child a tour. Reunion & Awards Trust me, nothing our Admissions folks, student ambas 03 sadors, friendly faculty of staff could say that would have 2012 Time & Eternity Honorees matched this tour. I watched as he reverently led his child into the chapel; 08 there were mentions of retreat days, religion teachers, and Together We Can Knock One Out of the Park private prayers. He walked proudly through the halls, want ing to straighten his tie in case an old nemesis was on guard. 10 Each classroom and lab called forth a special memory of a Marist Alumni: challenging course. When they reached the cafeteria and Excelling after Graduation the gym, once again, memories of performances, class and Reaching Their Goals mates, and even sounds and smells came rushing back and 12 gushing forth. With all of the choices for Catholic high Larry Malito's Farewell schools this alumnus, now father, shared his Marist pride and memories. The prospective student gladly put on the “red and white” 13 and later that week, joined more than six hundred students who applied to be 25 Years Later: Thousands of a part of the Class of 2016. -

Ginosko Literary Journal #17 Winter 2015�16 73 Sais Ave San Anselmo CA 94960

1 Ginosko Literary Journal #17 Winter 2015-16 www.GinoskoLiteraryJournal.com 73 Sais Ave San Anselmo CA 94960 Robert Paul Cesaretti, Editor Member CLMP Est. 2002 Writers retain all copyrights Cover Art “Beach” by Sarah Angst www.SarahAngst.com 2 Ginosko (ghin-océ-koe) A Greek word meaning to perceive, understand, realize, come to know; knowledge that has an inception, a progress, an attainment. The recognition of truth from experience. γινώσκω 3 To write the red of a tomato before it is mixed into beans for chili is a form of praise. To write an image of a child caught in war is confession or petition or requiem. To write grief onto a page of lined paper until tears blur the ink is often the surest access to giving or receiving forgiveness. To write a comic scene is grace and beatitude. To write irony is to seek justice. To write admission of failure is humility. To be in an attitude of praise or thanksgiving, to rage against God, or to open one's inner self and listen, is prayer. To write tragedy and allow comedy to arise between the lines is miracle and revelation. Pat Schneider 4 C O N T E N T S Say it with Feathers Jay Merill Sainthood Old Woman Hanging Out Wash High Contrast Mitchell Krockmalnik Grabois HE DIDN’T REFUSE Sreedhevi Iyer The Waters of Babylon Andrew Lee-Hart Breast Fragments When the World Was Tender The Wolves Have Sheared the Sun The Prophet of Horus Grant Tabard Conversations in an Idle Car Filling in Jack C Buck The Man Who Lost Everything Erica Verrillo Doused Your Summer Dress Magenta Stockings Promenade John Greiner Dead Fish Jono Naito Misnamed Ghetto Melissa Brooks A Country Girl Rudy Ravindra 5 Heavy Compulsion Samuel Vargo The Company of Strangers Michael Campagnoli Lions Venetian Balloons C. -

Triple J Hottest 100 of the Decade Voting List: AZ Artists

triple j Hottest 100 of the Decade voting list: A-Z artists ARTIST SONG 360 Just Got Started {Ft. Pez} 360 Boys Like You {Ft. Gossling} 360 Killer 360 Throw It Away {Ft. Josh Pyke} 360 Child 360 Run Alone 360 Live It Up {Ft. Pez} 360 Price Of Fame {Ft. Gossling} #1 Dads So Soldier {Ft. Ainslie Wills} #1 Dads Two Weeks {triple j Like A Version 2015} 6LACK That Far A Day To Remember Right Back At It Again A Day To Remember Paranoia A Day To Remember Degenerates A$AP Ferg Shabba {Ft. A$AP Rocky} (2013) A$AP Rocky F**kin' Problems {Ft. Drake, 2 Chainz & Kendrick Lamar} A$AP Rocky L$D A$AP Rocky Everyday {Ft. Rod Stewart, Miguel & Mark Ronson} A$AP Rocky A$AP Forever {Ft. Moby/T.I./Kid Cudi} A$AP Rocky Babushka Boi A.B. Original January 26 {Ft. Dan Sultan} Dumb Things {Ft. Paul Kelly & Dan Sultan} {triple j Like A Version A.B. Original 2016} A.B. Original 2 Black 2 Strong Abbe May Karmageddon Abbe May Pony {triple j Like A Version 2013} Action Bronson Baby Blue {Ft. Chance The Rapper} Action Bronson, Mark Ronson & Dan Auerbach Standing In The Rain Active Child Hanging On Adele Rolling In The Deep (2010) Adrian Eagle A.O.K. Adrian Lux Teenage Crime Afrojack & Steve Aoki No Beef {Ft. Miss Palmer} Airling Wasted Pilots Alabama Shakes Hold On Alabama Shakes Hang Loose Alabama Shakes Don't Wanna Fight Alex Lahey You Don't Think You Like People Like Me Alex Lahey I Haven't Been Taking Care Of Myself Alex Lahey Every Day's The Weekend Alex Lahey Welcome To The Black Parade {triple j Like A Version 2019} Alex Lahey Don't Be So Hard On Yourself Alex The Astronaut Not Worth Hiding Alex The Astronaut Rockstar City triple j Hottest 100 of the Decade voting list: A-Z artists Alex the Astronaut Waste Of Time Alex the Astronaut Happy Song (Shed Mix) Alex Turner Feels Like We Only Go Backwards {triple j Like A Version 2014} Alexander Ebert Truth Ali Barter Girlie Bits Ali Barter Cigarette Alice Ivy Chasing Stars {Ft. -

Blue Skin, Yellow Flesh Candace Wiley Clemson University, Candace [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 8-2009 Blue Skin, Yellow Flesh Candace Wiley Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Wiley, Candace, "Blue Skin, Yellow Flesh" (2009). All Theses. 638. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/638 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BLUE SKIN, YELLOW FLESH A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts English by Candace G. Wiley August 2009 Accepted by: Dr. Keith Morris, Committee Chair Dr. Rhondda Thomas Dr. Brian McGrath ABSTRACT Set in November 2009 in the United States South, Blue Skin, Yellow Flesh will eventually cover eleven days and will be separated into two parts—before and after Thecla’s funeral. It begins the Tuesday after Thecla dies and ends the day after Thanksgiving. The major conflict involves Thecla’s death, how it affects her family, and how the family deals with the concept of family. Other important conflicts are Tam and Lynn’s marriage, JoJo’s sexual orientation, Lynn’s affect on her children, and Julius’s trek toward death. This novel excerpt consists of seven chapters, submitted in partial fulfillment of Clemson University’s Master of Arts degree in English Literature. ii DEDICATION For my grandparents, whom I hope this novel excerpt honors, for the rest of my family (biological and adopted), for Angelica, my sister who put me on a fast, which started the first chapter. -

ARIA AUSTRALIAN ARTIST SINGLES CHART WEEK COMMENCING 18 JANUARY, 2021 TW LW TI HP TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO

CHART KEY <G> GOLD 35000 UNITS <P> PLATINUM 70000 UNITS TW THIS WEEK LW LAST WEEK TI TIMES IN HP HIGH POSITION ARIA AUSTRALIAN ARTIST SINGLES CHART WEEK COMMENCING 18 JANUARY, 2021 TW LW TI HP TITLE Artist CERTIFIED COMPANY CAT NO. 1 1 6 1 WITHOUT YOU The Kid Laroi SME US-SM1-20-06586 2 2 9 2 FLY AWAY Tones and I BAD/SME US-AT2-20-06865 3 3 12 1 SO DONE The Kid Laroi <P> COL/SME G0100044686111 4 5 18 1 ONE TOO MANY Keith Urban & P!nk SME/EMI 3505892 5 4 88 1 DANCE MONKEY Tones and I <P>13 BAD/SME G010004106308O 6 6 8 5 SEND IT! Hooligan Hefs WAR AU-WA0-20-00659 7 7 46 1 THIS CITY Sam Fischer <P>2 RCA/SME G010004220734M 8 12 34 2 TOGETHER Sia ATL/WAR US-AT2-20-02976 9 9 78 2 NEVER SEEN THE RAIN Tones and I <P>5 BAD/SME G010004122663J 10 8 30 2 EVERYBODY RISE Amy Shark <P> WRC/SME G010004271081C 11 13 10 4 ALWAYS DO The Kid Laroi COL/SME US-SM1-20-06583 12 11 144 1 YOUNGBLOOD 5 Seconds Of Summer <P>11 CAP/EMI 6748358 13 10 67 2 RUSHING BACK Flume Feat. Vera Blue <G> FCL FCL283 14 14 133 1 BE ALRIGHT Dean Lewis <P>10 ISL/UMA 6769790 15 16 24 3 GO The Kid Laroi Feat. Juice WRLD <P> UMA/SME G010004402179U 16 15 56 2 THE LESS I KNOW THE BETTER Tame Impala <P>4 MOD/UMA AU-UM7-15-00303 17 R/E 13 13 ENERGY Stace Cadet & KLP <G> SME G010004403318O 18 19 37 5 I'M GOOD? Hilltop Hoods <P> HTH/UMA 0717025 19 R/E 83 1 CONFIDENCE Ocean Alley <P> ORCH AU-ZN3-17-00127 20 17 37 5 KHE SANH Cold Chisel UMA AU-U74-11-00002 © 1988-2021 Australian Recording Industry Association Ltd. -

BTS' 'Life Goes On' Launches As Historic No. 1 on Billboard Hot

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth NOVEMBERAirplay 30, 2020 Page 1 of 36 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE BTS’ ‘Life Goes On’ Launches as Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music GroupHistoric Nashville), debuts at No. 1 on No. Billboard’s 1lion on audience Billboard impressions, up 16%). Hot 100 Top• CountryBTS Earns Albums Fifth chartNo. dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earned1 Album 46,000 on Billboardequivalent album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cording200 toChart Nielsen With Music/MRC ‘Be’ Data. and totalBY GARY Country TRUST Airplay No. 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends Southside marks Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chart• and Why fourth The Musictop 10. It followsBTS freshman’ “Life Goes LP On” soars onto the Billboard Hot ending Nov. 26,Young’s according first ofto six Nielsen chart entries,Music/MRC “Sleep With- Publishing Market Is Montevallo, which arrived at the summit songs in chart No - at No. 1. Data. It alsoout earned You,” 410,000 reached No.radio 2 in airplay December audience 2016. He Still Booming — And 100 vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks.The song To date, is the South Korean septet’s third Hot 100 impressionsfollowed in the week with the ending multiweek Nov. -

Liner Notes for New World Records CD 80611-2

FROM BARRELHOUSE TO BROADWAY: THE MUSICAL ODYSSEY OF JOE JORDAN By RICK BENJAMIN Joe Jordan (1882–1971) is the musician who most directly links authentic African-American ragtime with the Golden Age of the American musical theater. An artist of great versatility—he was a gifted pianist, composer, songwriter, arranger, conductor, organizer, promoter, and educator—Jordan was also remarkable for his extraordinary successes in an era of appalling racial discrimination. Threads of his long and fascinating career intertwined and intersected with historical figures as diverse as Fanny Brice, Scott Joplin, Orson Welles, James P. Johnson, Florenz Ziegfeld, Thomas “Fats” Waller, W.C. Handy, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, Williams & Walker, Ethel Merman, Cole & Johnson, Ginger Rogers, Ernest Hogan, Will Marion Cook, Tom Turpin, and a host of others. Although he had little formal musical training, Joe Jordan composed, orchestrated, and conducted dozens of important musical productions in Chicago and New York, and wrote more than six hundred songs, several of them nationwide hits. He was also a businessman of such keen ability that by the late 1910s he had become one of the wealthiest blacks in the nation. Yet, with the passage of time, awareness of Joe Jordan’s music and career has faded. But a study of his rich creative legacy reveals much of importance to current and future generations. It is time for Joe Jordan’s amazing story —and music—to be heard once again. Joseph Zachariah Taylor Jordan entered the world on February 11, 1882. The son of Zachariah and Josephine Jordan, he was born in Cincinnati, Ohio. For a creative and inquisitive child, the “Queen City of the West” was indeed a fortunate place to be. -

The Top Dance Songs of 2019 1

th 45 Year THE TOP DANCE SONGS OF 2019 1. HIGHER LOVE – Kygo & Whitney Houston (RCA) 124/104 51. YOU LITTLE BEAUTY – Fisher (Astralwerks/Capitol) 124 2. PIECE OF YOUR HEART – Meduza ft. Goodboys (Capitol) 124 52. GO SLOW – Gorgon City & Kaskade ft. ROMEO (Capitol) 124 3. I DON’T CARE – Ed Sheeran & Justin Bieber (Atlantic) 122/102 53. SUMMER DAYS – Martin Garrix ft. Macklemore & Patrick Stump (RCA) 126/114 4. SUCKER – Jonas Brothers (Republic) 126/138 54. ON MY WAY – Alan Walker, Sabrina Carpenter & Farruko (RCA) 120/85 5. BAD GUY – Billie Eilish (Interscope) 126/135 55. HEY LOOK MA, I MADE IT – Panic! At The Disco (Atlantic) 124/108 6. CON CALMA – Daddy Yankee & Katy Perry ft. Snow (El Cartel/Capitol) 109/94 56. FIND U AGAIN – Mark Ronson & Camila Cabello (RCA) 124/104 7. SENORITA – Shawn Mendes & Camila Cabello (Republic) 124/117 57. BREAK UP WITH YOUR GIRLFRIEND, I’M BORED – Ariana Grande (Republic) 124/85 8. 7 RINGS/THANK U NEXT – Ariana Grande (Republic) 126/70, 124/107 58. SELFISH – Dimitri Vegas & Like Mike ft. Era Istrefi (Arista) 126/96 9. DANCING WITH A STRANGER – Sam Smith & Normani (Capitol) 123/103 59. 365 – Zedd & Katy Perry (Interscope) 124/98 10. DANCE MONKEY – Tones and I (Elektra) 122/98 60. BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE – Ed Sheeran ft. Khalid (Atlantic) 120/93 11. OLD TOWN ROAD – Lil Nas X ft. Billy Ray Cyrus (Columbia) 124/70 61. QUE CALOR – Major Lazer ft. J Balvin & El Alfa (Mad Decent) 126 12. SO CLOSE – NOTD & Felix Jaehn ft. Georgia Ku & Captain Cuts (Republic) 126 62.