Love of My Life Peter M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bailey Warren Senior Honors Thesis Project.Pdf

1 Foreword “Dimitri Mitropoulos was asked if he could explain the extraordinary effect his conducting had on orchestra and audience alike, and he answered that he wouldn’t even try to explain it, for fear that he might become like the centipede who was asked by a humble little bug which of his hundred legs moved first when he walked. The centipede, responding to the admiration with immense pride, began to analyze the question, and has not walked since.” This excerpt is from Madeleine L’Engle’s book A Circle of Quiet. In the same chapter as this quote, she explains how when Beethoven performed his sonatas and was immediately asked what his sonatas meant, he simply sat down and played them once more. What L’Engle is trying to get at is if one could truly explain their art, there would have been no reason to create the art in the first place. In response to Mitropoulos’ quote she says, “we’re apt to get tangled up in legs when we begin to analyze the creative process.” Throughout the process of creating this album I have embedded a lot of myself into the project. So much of it has become inherently who I am that I feel as if I have become too close to it. This is the first creative project that I have ever completed to this caliber, and the first collection of musical works that is thoroughly mine. Putting it into words doesn’t seem to do it justice. Analysis can only do so much in describing the nuances of art. -

The Counselor

Volume 86 - Issue 8 November 1, 2013 and said that she never wanted to grow up. Of course, Spangler became aware of her body as she grew a little Embracing the strange older, but she has still kept some of her childlike whimsy. Katie Petts said that she would compare Spangler to someone like Jack Sparrow. “She’s the odd character that everyone loves,” Petts said. But, frankly, not everyone loves Spangler. Some make statements such as, “She’s off in her own little world singing songs. I can’t connect with her,” or “I just want to tell her that she is not making the world better by being so obnoxious,” or “I don’t get her at all, nor do I want to.” It’s not as if her strangeness goes away when one gets to know her. Actually, the more one knows her, the stranger she seems. A good place to begin the search for evidence of this deeper strangeness, is in her room. Spangler’s room hosts many oddities. Piles of clothing, dishes and books are spewed sporadically on the floor. An assortment of hats she wears daily are stacked unorderly atop her vanity, PHOTO BY TERESA ODERA and a collection of action figures she BY SARAH ODOM decibel with an equally unexplainable “I would compare her to Lady Gaga,” plans to display are in an open box near The screen at the front of the chapel color that is both bright and dark at Jeanie Fairchild, an acquaintance of her window. In the corner, there is a shows lyrics to worship songs that the same time. -

ICN1886-04-08.Pdf

mm jai:ilia''qiii^ sbbviiigVflraternlty,f' Is alwaya welooine ,to Dry Oooils.—Bnrnham & Company. Legal. Two WMk)B (h>m '.to-day Preatdent Mrs. Race Is very slok. iKDBR OP PUBLICATION.-8TATK OP WlUetta of the Agricultural college A. D. Bnirdsley's father la visiting _ MlohlaaMichiganu, ..In. th.u Circuit Court for tho Thursdnjr, April 1, W hlriri. County of Initham-Iiam-IIIi CliancoryCliancory,. will addriesis the ol lib on "Moslems Mrs. A. O. Walker of Detroit Is Lillian Oamblo, Complainant,'Complainant,)) &nd Mormons." As this will probably VB, Fanners* Club. ipuoh better. Kll Oamblo, Dofondant. be the laafr regular meeting for.some It satlaraclorily appearing to thin court by Miss Luclna Beardsley was home affidavit on fllo that tlio dcfondant, £11 aambto, . dtUB BooMB, March 27, ISSis. weeks thiere will be a large attendance. over Sunday. ia not > roaldent of this atato, hut retidoa at the • The oluti^^^^^^^ full up UKlay. Ladles eapeoially Invited. village or Nunda,iu thoHtatool Now York, on. .1 Chas. McKuigbt Is going to Holly moUon of K. D, Lewia, compltlnant'a aollcltor. Nothlhpnew In inarket.reporta. Quite L. H. Ivjiss, Secretary. for treatment. It la ordered that tho aald dulCndant, £11 Gamble, Claude and Etta West have returned Display of Spring Novelties excels that of any cause hla appoaranco to bo entorod horcln wltbln a quantity of seeds graced the tables four montha from tho data of thla order, and in For neuralgia, rbeumatism,'lumbago, from their visit at Manistee. and the meeting was one of much li> previous season, in point of elegance and var caao of hla appoaranco that ho cauae his anawer gout,' Bwellinga, burns, wounds, etc., There will be a mum social at Mrs. -

Alessia Cara Seventeen Download Song

Alessia cara seventeen download song CLICK TO DOWNLOAD About "Seventeen" Song "Seventeen" is a Pop song by Alternative R&B, soulpop, R&B, Indie pop singer "Alessia Cara" from the studio album "Know-It-All".This song's duration is ( min) and available in digital format at the largest music online shopping store iTunes & Amazon Music. The song Seventeen is written by Oak, Andrew "Pop" Wansel, Ronald White, William Robinson Jr., Samuel . Seventeen MP3 Song by Alessia Cara from the album Know-It-All (Deluxe). Download Seventeen song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru and listen Know-It-All (Deluxe) Seventeen song offline. rows · Alessia Cara (born Alessia Caracciolo on July 11, ) is a Canadian singer-songwriter . Know-It-All is the debut studio album by Canadian singer and songwriter Alessia renuzap.podarokideal.ru was released on November 13, through Def Jam renuzap.podarokideal.ru album followed the release of her debut extended play (EP) Four Pink Walls (), which Cara regarded as a preview of the album. Know-It-All contains the five original songs from Four Pink Walls as well as five new songs recording for the renuzap.podarokideal.ru: R&B, pop. “Seventeen” is the opening track of Alessia Cara’s debut EP, Four Pink Walls and her first studio album, Know-It-All. The song contrasts her younger self and listening to her parents' advice. Download Music Alessia Cara – Seventeen. Ohh oh oh oh oh oh Oh oh oh oh Ohh oh oh oh oh oh Oh oh oh oh. My daddy says that life comes at you fast We all like blades of grass We come to prime and in time we just wither away And it all changes My view with a looking glass won’t catch the past Only photographs remind us of the passing of days. -

What's on DEBBIE TRAVIS the TV STAR CHATS to HELLO!

What’s On BOOK Exclusive ‘My kids thought DEBBIE TRAVIS I was crazy. I THE TV STAR CHATS TO HELLO! ABOUT FAMILY LIFE, FOLLOWING YOUR guess I did DREAMS AND HER ADVENTURES UNDER THE TUSCAN SUN become deranged t’s almost impossible to pin down Debbie Tra- How long did the process take? It took about live. And every time we visited I felt so healthy after a bit!’ I vis! In addition to being a TV star, bestselling two years. It was a lot of research. I interviewed and so alive and full of vitality. We had this dream author, newspaper columnist, public speaker a lot of people about starting again, the risks of buying a little house, and the dream kept and head of her own business empire, the you could take, getting rid of the fear, and all growing and growing until we started looking U.K.-born lifestyle icon has managed to convert the questions that we all have. Self-doubt is the at 40-bedroom monasteries! Then I thought: an entire 13th-century Tuscan farmhouse into biggest factor for everyone, and so I really want- “What if I shared it? What if I invited people to a luxury retreat. ed to address that. live this dream with me?” All in a day’s work, it seems, for the 58-year-old mom of two, who tells Hello!: “I love rising to a What do you want readers to take away from While you were going through this entire jour- challenge.” And her latest book tells this book? Everybody has a dream and ney, how supportive were your family for you? us how it all began. -

Teacher Growing Pains

The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning Volume 7 Winter 2001-2002 Article 5 2001 Teacher Growing Pains Carolina Mancuso Brooklyn College, CUNY Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl Part of the Creative Writing Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Curriculum and Social Inquiry Commons, Disability and Equity in Education Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Educational Psychology Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Instructional Media Design Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Other Education Commons, Special Education and Teaching Commons, and the Teacher Education and Professional Development Commons Recommended Citation Mancuso, Carolina (2001) "Teacher Growing Pains," The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning: Vol. 7 , Article 5. Available at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl/vol7/iss1/5 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Volunteer, Open Access, Library Journals (VOL Journals), published in partnership with The University of Tennessee (UT) University Libraries. This article has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning by an authorized editor. For more information, please visit https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl. Teacher Growing Pains Cover Page Footnote Carolina Mancuso, Assistant Professor in Literacy Education at Brooklyn College, CUNY, is currently researching the effects on new teachers of reflective practices in teacher education. She can be reached at . This essay is available in The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning: https://trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl/vol7/iss1/5 20 JAEPL, Vol. 7, Winter 2001–2002 Teacher Growing Pains Carolina Mancuso Solution comes only by getting away from the meaning of terms that is already fixed upon and coming to see the conditions from another point of view, and hence in a fresh light. -

SONG ARTIST 375 Roar

# SONG ARTIST 400 We're All In This Together Ben Lee 399 Be The One Dua Lipa 398 Take My Breath Away Berlin 397 Treat You Better Shawn Mendes 396 The Fighter Keith Urban Feat Carrie Underwood 395 I'm Still On You're Side Jimmy Barnes 394 Dance Monkey Tones & I 393 Just Like Fire Pink 392 One Dance Drake Feat Wizkid & Kyla 391 Fire & The Flood Vance Joy 390 Hide Away Daya 389 Don't Wanna Know Maroon 5 Feat Kendrick Lamar 388 Stonger Kanye 387 Dancin with myself Billy Idol 386 London Calling Clash 385 Ain't Nobody (Loves Me Better) Felix Jaehn Feat Jasmine Thompson 384 10,000 Hours Dan + Shay & Justin Bieber 383 You Don’t Know Me Jax Jones Feat RAYE 382 You Need To Calm Down Taylor Swift 381 American Woman Lenny Kravitz 380 You Keep Me Hangin On Kim Wilde 379 Senorita Shawn Mendes & Camila Cabello 378 Whenever, Wherever Shakira 377 The Middle Zedd Feat Maren Morris & Grey 376 Get Lucky Daft Punk Feat Pharrell Williams 375 Roar Katy Perry 374 Heroes David Bowie 373 Hey Ya! Outkast 372 Left Outside Alone Anastasia 371 24K Magic Bruno Mars 370 In My Blood The Veronicas 369 Addicted To You Avicii 368 Welcome to the Jungle Guns N Roses 367 Scars To Your Beautiful Alessia Cara 366 Que Sera Justice Crew 365 I Love You Always Forever Betty Who 364 Strip That Down Liam Payne Feat Quavo 363 Starboy The Weeknd Feat Daft Punk 362 Issues Julia Michaels 361 Rather Be Clean Bandit Feat Jess Glynne 360 Your The Voice John Farnham 359 Moves Like Jagger Maroon 5 Feat Christina Aguilera 358 Am I Wrong Nico & Vinz 357 Take Me To Church Hozier 356 Mr Brightside -

Dreams-041015 1.Pdf

DREAMS My Journey with Multiple Sclerosis By Kristie Salerno Kent DREAMS: MY JOURNEY WITH MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS. Copyright © 2013 by Acorda Therapeutics®, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. Author’s Note I always dreamed of a career in the entertainment industry until a multiple sclerosis (MS) diagnosis changed my life. Rather than give up on my dream, following my diagnosis I decided to fight back and follow my passion. Songwriting and performance helped me find the strength to face my challenges and help others understand the impact of MS. “Dreams: My Journey with Multiple Sclerosis,” is an intimate and honest story of how, as people living with MS, we can continue to pursue our passion and use it to overcome denial and find the courage to take action to fight MS. It is also a story of how a serious health challenge does not mean you should let go of your plans for the future. The word 'dreams' may end in ‘MS,’ but MS doesn’t have to end your dreams. It has taken an extraordinary team effort to share my story with you. This book is dedicated to my greatest blessings - my children, Kingston and Giabella. You have filled mommy's heart with so much love, pride and joy and have made my ultimate dream come true! To my husband Michael - thank you for being my umbrella during the rainy days until the sun came out again and we could bask in its glow together. Each end of our rainbow has two pots of gold… our precious son and our beautiful daughter! To my heavenly Father, thank you for the gifts you have blessed me with. -

WHS English Department Summer Reading Extra Credit Assignment

WHS English Department Summer Reading Extra Credit Assignment Summer reading is encouraged but not required this year. If you are interested, it will count as extra credit on your 1st Marking Period Grade. You are to choose ONE of the assessments for ONE of the recommended grade-level novels below. If your work is thorough, completed, and submitted on the first day of school, you will be given an additional “Reading Literature'' and a “21st Century Grade”. * Though this is the recommended list, you may select another book to read only if it is approved by your current English teacher. This must be done by June 17th.* Please remember, you must do this project on a book that you have a) not read before and b) is grade/reading level appropriate. Write a Character Point of View Letter Write a letter from the point of view of one of the characters in your book to a “potential” reader. Your goal is to have the character write a persuasive letter to this “potential” reader, trying to convince him/her why he should read the book....a sort of “testimonial” advertisement for the book. Include a MINIMUM of three specific events in the book from this character’s point of view. Since your character is advertising the book, you may not want to give away the ending, but you could comment on events that lead up to the ending and end with a cliffhanger comment in the letter. Remember...YOU are not writing the letter, but your selected CHARACTER is. Try to capture the essence/personality of that character...how would that character write a letter? Timeline Project Create a timeline showing the five most significant points in the novel. -

“Together We Can Knock One out of the Park.”

THE Winter 2012 Where Marist Alumni Meet for News “Together we can knock one out of the park.” – Br. Patrick McNamara, fms President, Marist High School Letter From Brother Patrick Winter 2012 reunion&awards 02 Dear Marist Family, Letter From Brother Patrick Marist recently hosted its last Open House for the Class of 2016. More than 03 1,500 students visited the campus this year, and on this last chance before the 2012 Alumni BIG ENTRANCE TEST, I watched a Marist grad giving his child a tour. Reunion & Awards Trust me, nothing our Admissions folks, student ambas 03 sadors, friendly faculty of staff could say that would have 2012 Time & Eternity Honorees matched this tour. I watched as he reverently led his child into the chapel; 08 there were mentions of retreat days, religion teachers, and Together We Can Knock One Out of the Park private prayers. He walked proudly through the halls, want ing to straighten his tie in case an old nemesis was on guard. 10 Each classroom and lab called forth a special memory of a Marist Alumni: challenging course. When they reached the cafeteria and Excelling after Graduation the gym, once again, memories of performances, class and Reaching Their Goals mates, and even sounds and smells came rushing back and 12 gushing forth. With all of the choices for Catholic high Larry Malito's Farewell schools this alumnus, now father, shared his Marist pride and memories. The prospective student gladly put on the “red and white” 13 and later that week, joined more than six hundred students who applied to be 25 Years Later: Thousands of a part of the Class of 2016. -

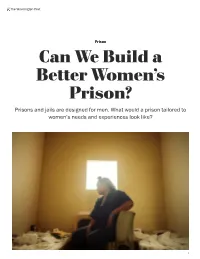

Can We Build a Better Women's Prison?

The Washington Post Prison Can We Build a Better Women’s Prison? Prisons and jails are designed for men. What would a prison tailored to women’s needs and experiences look like? / Sherita Alexander in her cell in a “high-level” block (reserved for women who are considered a risk for violent behavior or who are not participating in a work program) at Las Colinas Detention and Reentry Facility for women in San Diego County, Calif. (Brian L. Frank for The Washington Post) By Keri Blakinger OCTOBER 28, 2019 auren Johnson walked into the aging Travis County jail L just outside Austin on a sunny Friday in July 2018 and steeled herself. Every time she passed through the door and the smell hit her, it all came rushing back: the humiliation of being shackled while nine months pregnant. The pang of seeing her children from behind a glass barrier. How she’d had to improvise with what little she had, crafting makeshift bras out of the disposable mesh underwear the jail provided. Between 2001 and 2010, she’d been in and out of the facility six times. Altogether, she’d spent about 3½ years of her life incarcerated. / Now she was returning to the jail, eight years after the last time she’d been released. But this time, it was to ask the incarcerated women questions that would’ve been unfathomable to her during her time there: What did they want? How could their experience be improved? Johnson wore bold prints and her best jewelry that morning, and purposefully doused herself in perfume. -

Ginosko Literary Journal #17 Winter 2015�16 73 Sais Ave San Anselmo CA 94960

1 Ginosko Literary Journal #17 Winter 2015-16 www.GinoskoLiteraryJournal.com 73 Sais Ave San Anselmo CA 94960 Robert Paul Cesaretti, Editor Member CLMP Est. 2002 Writers retain all copyrights Cover Art “Beach” by Sarah Angst www.SarahAngst.com 2 Ginosko (ghin-océ-koe) A Greek word meaning to perceive, understand, realize, come to know; knowledge that has an inception, a progress, an attainment. The recognition of truth from experience. γινώσκω 3 To write the red of a tomato before it is mixed into beans for chili is a form of praise. To write an image of a child caught in war is confession or petition or requiem. To write grief onto a page of lined paper until tears blur the ink is often the surest access to giving or receiving forgiveness. To write a comic scene is grace and beatitude. To write irony is to seek justice. To write admission of failure is humility. To be in an attitude of praise or thanksgiving, to rage against God, or to open one's inner self and listen, is prayer. To write tragedy and allow comedy to arise between the lines is miracle and revelation. Pat Schneider 4 C O N T E N T S Say it with Feathers Jay Merill Sainthood Old Woman Hanging Out Wash High Contrast Mitchell Krockmalnik Grabois HE DIDN’T REFUSE Sreedhevi Iyer The Waters of Babylon Andrew Lee-Hart Breast Fragments When the World Was Tender The Wolves Have Sheared the Sun The Prophet of Horus Grant Tabard Conversations in an Idle Car Filling in Jack C Buck The Man Who Lost Everything Erica Verrillo Doused Your Summer Dress Magenta Stockings Promenade John Greiner Dead Fish Jono Naito Misnamed Ghetto Melissa Brooks A Country Girl Rudy Ravindra 5 Heavy Compulsion Samuel Vargo The Company of Strangers Michael Campagnoli Lions Venetian Balloons C.