Teacher Growing Pains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Counselor

Volume 86 - Issue 8 November 1, 2013 and said that she never wanted to grow up. Of course, Spangler became aware of her body as she grew a little Embracing the strange older, but she has still kept some of her childlike whimsy. Katie Petts said that she would compare Spangler to someone like Jack Sparrow. “She’s the odd character that everyone loves,” Petts said. But, frankly, not everyone loves Spangler. Some make statements such as, “She’s off in her own little world singing songs. I can’t connect with her,” or “I just want to tell her that she is not making the world better by being so obnoxious,” or “I don’t get her at all, nor do I want to.” It’s not as if her strangeness goes away when one gets to know her. Actually, the more one knows her, the stranger she seems. A good place to begin the search for evidence of this deeper strangeness, is in her room. Spangler’s room hosts many oddities. Piles of clothing, dishes and books are spewed sporadically on the floor. An assortment of hats she wears daily are stacked unorderly atop her vanity, PHOTO BY TERESA ODERA and a collection of action figures she BY SARAH ODOM decibel with an equally unexplainable “I would compare her to Lady Gaga,” plans to display are in an open box near The screen at the front of the chapel color that is both bright and dark at Jeanie Fairchild, an acquaintance of her window. In the corner, there is a shows lyrics to worship songs that the same time. -

Alessia Cara Seventeen Download Song

Alessia cara seventeen download song CLICK TO DOWNLOAD About "Seventeen" Song "Seventeen" is a Pop song by Alternative R&B, soulpop, R&B, Indie pop singer "Alessia Cara" from the studio album "Know-It-All".This song's duration is ( min) and available in digital format at the largest music online shopping store iTunes & Amazon Music. The song Seventeen is written by Oak, Andrew "Pop" Wansel, Ronald White, William Robinson Jr., Samuel . Seventeen MP3 Song by Alessia Cara from the album Know-It-All (Deluxe). Download Seventeen song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru and listen Know-It-All (Deluxe) Seventeen song offline. rows · Alessia Cara (born Alessia Caracciolo on July 11, ) is a Canadian singer-songwriter . Know-It-All is the debut studio album by Canadian singer and songwriter Alessia renuzap.podarokideal.ru was released on November 13, through Def Jam renuzap.podarokideal.ru album followed the release of her debut extended play (EP) Four Pink Walls (), which Cara regarded as a preview of the album. Know-It-All contains the five original songs from Four Pink Walls as well as five new songs recording for the renuzap.podarokideal.ru: R&B, pop. “Seventeen” is the opening track of Alessia Cara’s debut EP, Four Pink Walls and her first studio album, Know-It-All. The song contrasts her younger self and listening to her parents' advice. Download Music Alessia Cara – Seventeen. Ohh oh oh oh oh oh Oh oh oh oh Ohh oh oh oh oh oh Oh oh oh oh. My daddy says that life comes at you fast We all like blades of grass We come to prime and in time we just wither away And it all changes My view with a looking glass won’t catch the past Only photographs remind us of the passing of days. -

What's on DEBBIE TRAVIS the TV STAR CHATS to HELLO!

What’s On BOOK Exclusive ‘My kids thought DEBBIE TRAVIS I was crazy. I THE TV STAR CHATS TO HELLO! ABOUT FAMILY LIFE, FOLLOWING YOUR guess I did DREAMS AND HER ADVENTURES UNDER THE TUSCAN SUN become deranged t’s almost impossible to pin down Debbie Tra- How long did the process take? It took about live. And every time we visited I felt so healthy after a bit!’ I vis! In addition to being a TV star, bestselling two years. It was a lot of research. I interviewed and so alive and full of vitality. We had this dream author, newspaper columnist, public speaker a lot of people about starting again, the risks of buying a little house, and the dream kept and head of her own business empire, the you could take, getting rid of the fear, and all growing and growing until we started looking U.K.-born lifestyle icon has managed to convert the questions that we all have. Self-doubt is the at 40-bedroom monasteries! Then I thought: an entire 13th-century Tuscan farmhouse into biggest factor for everyone, and so I really want- “What if I shared it? What if I invited people to a luxury retreat. ed to address that. live this dream with me?” All in a day’s work, it seems, for the 58-year-old mom of two, who tells Hello!: “I love rising to a What do you want readers to take away from While you were going through this entire jour- challenge.” And her latest book tells this book? Everybody has a dream and ney, how supportive were your family for you? us how it all began. -

WHS English Department Summer Reading Extra Credit Assignment

WHS English Department Summer Reading Extra Credit Assignment Summer reading is encouraged but not required this year. If you are interested, it will count as extra credit on your 1st Marking Period Grade. You are to choose ONE of the assessments for ONE of the recommended grade-level novels below. If your work is thorough, completed, and submitted on the first day of school, you will be given an additional “Reading Literature'' and a “21st Century Grade”. * Though this is the recommended list, you may select another book to read only if it is approved by your current English teacher. This must be done by June 17th.* Please remember, you must do this project on a book that you have a) not read before and b) is grade/reading level appropriate. Write a Character Point of View Letter Write a letter from the point of view of one of the characters in your book to a “potential” reader. Your goal is to have the character write a persuasive letter to this “potential” reader, trying to convince him/her why he should read the book....a sort of “testimonial” advertisement for the book. Include a MINIMUM of three specific events in the book from this character’s point of view. Since your character is advertising the book, you may not want to give away the ending, but you could comment on events that lead up to the ending and end with a cliffhanger comment in the letter. Remember...YOU are not writing the letter, but your selected CHARACTER is. Try to capture the essence/personality of that character...how would that character write a letter? Timeline Project Create a timeline showing the five most significant points in the novel. -

Summer Reading Grade 6

History With a Dash of Fiction Full of Beans Jennifer Holm The New Dealers arrive in Key West in the middle of the Great Depression and plan to turn it into a tourist destination. Beans just wants to make a dime or two and his plans keep going awry. Also Turtle in Paradise. Gold Seer Trilogy: Walk on Earth a Stranger—a series Rae Carson Leah has an extraordinary talent to sense when gold is near. When her parents are robbed and murdered, she disguises herself as a boy and leaves the only home she's ever known to join a wagon train for a new gold rush in California. Can she keep her identity a secret and survive this new adventure? Also Like a River Glorious & Into the Bright Unknown. Iron Thunder Avi Thirteen-year-old Tom Carroll finds work at the Brooklyn Navy Yard on a secret project that may benefit the Northern armies during the Civil War. Pursued by spies from the South, he ends up in the middle of a sea battle. Will he find the courage to survive? The Night Diary—a 2021 Nutmeg Nominee Veera Hiranandani Nisha was ripped away from all she had ever known during India‟s 1947 Partition. Nisha, and her family have just days to leave their home. In a series of diary entries she describes her difficult journey to a new India. Nisha searches to find her identity after leaving everything behind. Nine, Ten: A September 11 Story—a 2019 Nutmeg Nominee Nora Baskin Two days before 9-11, four kids in different parts of the country are going about their lives. -

St. John Passion Johann Sebastian Bach

Great Music in a Great Space: St. John at St. John St. John Passion Johann Sebastian Bach Monday, 29 March 2021 7pm Concert ST. JOHN PASSION 2 St. John Passion, BWV 245 By Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) Kent Tritle, conductor Andrew Fuchs, Evangelist Joseph Beutel, Christus (Jesus) Amy Justman, soprano Kirsten Sollek, contralto Lawrence Jones, tenor Peter Stewart, bass-baritone The Cathedral Choir & Ensemble 1047 Lianne Coble, Ancilla (Maid) Scott Dispensa, Petrus (Peter) Michael Steinberger, Servus (Attendant) Lee Steiner, Servus (Attendant) Enrico Lagasca, Pilatus (Pilate) Cathedral Choir Soprano Alto Tenor Bass Lianne Coble Tracy Cowart Eric Sorrels Scott Dispensa Linda Jones Katie Geissinger Michael Steinberger Dominic Inferrera Nola Richardson Heather Petrie Lee Steiner Enrico Lagasca Elisa Singer Strom Margery Daley, Choral Contractor Ensemble 1047 Violin I Cello Flute Harpsichord Mitsuru Tsubota Arthur Fiacco, Jr. Sato Moughalian Renée Louprette Janet Axelrod Violin II Bass Organ Theresa Salomon Roger Wagner Oboe Raymond Nagem Diane Lesser Viola Viola da Gamba WIlliam Meredith Arthur Fiacco, Jr., Alissa Smith Sarah Cunningham Personnel Manager Bassoon Damian Primis CATHEDRAL MUSIC STAFF CATHEDRAL PRODUCTIONS STAFF Kent Tritle, Director of Music and Organist Christian Mardones, Director of Productions Raymond Nagem, Associate Music Director Issac Lopez, Productions Coordinator Bryan L. Zaros, Associate Choirmaster George Wellington, Audio Engineer Christina Kay, Music Administrator Jonathan Estabrooks, Video Designer Jie Yi, Music Administrator Bill Siegmund, Audio Assistant Samuel Kuffuor-Afriyie, Organ Scholar Richie Clarke, Audio Assistant Douglass Hunt, Organ Curator Nidal Qannari-Harvey, Videographer Roman Sotelo, Camera Operator Cole Marino, Subtitles Coordinator Special thanks to External Affairs and Public Education & Visitor Services for their assistance in coordinating the online platform. -

Growing Pains S1e2 Download Free Growing Pains S1e2 Download Free

growing pains s1e2 download free Growing pains s1e2 download free. Alessia Cara – The Pains of Growing Full leaked Album. Download link in MP3 ZIP/RAR formats. Artist: Alessia Cara Album: The Pains of Growing Year: 2018 Genre: Alternative Pop, R&B, Teen pop. Track list: 1. “Growing Pains” 2. “Not Today” 3. “I Don’t Want To” 4. “7 Days” 5. “Trust My Lonely” 6. “Wherever I Live” 7. “All We Know” 8. “A Little More” 9. “Comfortable” 10. “Nintendo Game” 11. “Out of Love” 12. “Girl Next Door” 13. “My Kind” 14. “Easier Said” 15. “Growing Pains (Reprise)” Growing pains complete series download. �Growing Pains� Kids Still Miss Their TV Dad, Alan Thicke - TODAY. Were can i find a growing pains series 7 torrent? Skip to main content. Growing Pains Complete Series. In Stock. I ordered this for my daughter, she was so excited because Growing Pains is one of her favorite shows. She wants to know when season 4 will out now! Add to cart. I'm so happy they finally decided to release the rest of the seasons on DVD. Sign in. Find showtimes, watch trailers, browse photos, track your Watchlist and rate your favorite movies and TV shows on your phone or tablet! IMDb More. Edit Growing Pains � Jason Seaver episodes, Joanna Kerns. Am ,glad to own on the whole Growing Pains season D. D collection of the show love it. I love Growing Pains ,because its a good show that evolves around a family that loves each other. An I am happy to own the entire series on D. -

PATRICK WARREN (Discography) Year Album / Project Artist Credit

PATRICK WARREN (Discography) 1/1/19 Recording Year Album / Project Artist Credit Label 2019 TBD Sara Bareilles Keyboards, String Arrangements 2018 TBD Elisa Composing, Conducting, producing Universal Italy 2018 All These Things Thomas Dybdahl Keyboards, Programming, Composer Piano, Wurlitzer Piano, Harmonium, 2018 Anthem Madeleine Peyroux String Arrangements, Dulcitone, Shouts, Composer 2018 Indigo Kandace Springs String Arrangements 2018 Over the Years… Graham Nash Wurlitzer Piano 2018 She Remembers Everything Rosanne Cash Mellotron, Piano 2018 String Theory Hanson Chamberlin, Group Member Superfly [Original Motion Picture 2018 Soundtrack] Future Strings 2018 The Pains of Growing Alessia Cara Strings 2018 Wanderer Cat Power Arranger, Strings Piano, Organ, Keyboards, Pump 2018 Whistle Down the Wind Joan Baez Organ, Tack Piano 2018 Years in the Making Loudon Wainwright III Piano 2017 Grace Lizz Wright Keyboards 2017 Happy Accidents Jamie Lawson String Arrangements Keyboards, Organ (Hammond), Jupiter Calling The Corrs 2017 Strings, Synthesizer 2017 Life. Love. Flesh. Blood Imelda May Keyboard Arrangements, Keyboards 2017 Love and Murder Leslie Mendelson Strings Bassoon, Flute, Organ, Piano, Strings, 2017 Lust for Life Lana Del Rey Synthesizer, Tack Piano, Waterphone 2017 Popular Van Hunt Conductor 2017 The Christmas Wish Herb Alpert Keyboards 2017 The Natalie Merchant Collection Natalie Merchant Chamberlin, Pump Organ 2017 Wonder: Introducing Natalie Merchant Natalie Merchant Chamberlin, Organ Conductor, Horn Arrangements, String Arrangements, -

![[REE 005] Programme Cover 10/26/05 10:47 AM Page Iii](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1569/ree-005-programme-cover-10-26-05-10-47-am-page-iii-4531569.webp)

[REE 005] Programme Cover 10/26/05 10:47 AM Page Iii

[REE 005] Programme Cover 10/26/05 10:47 AM Page iii ~ the 9th annual toronto reel asian international film festival ~ l si november 23 27, 2005 national spotlight: - ~ alaysia [REE 005] Programme Cover 10/26/05 10:47 AM Page iv ponsors GOVERNMENT FUNDERS CORPORATE SPONSORS FESTIVAL SPONSORS MEDIA SPONSORS AWARD SPONSORS EVENT SPONSORS COMMUNITY PARTNERS COMMUNITY CO-PRESENTERS Autoshare Canada Japan Society of Images Festival MyMediaBiz.com Dynamix Solutions Toronto (CJST) Inside Out Toronto Lesbian North American Association of Take One magazine Canadian Cambodian and Gay Film and Video Festival Asian Professionals (Toronto) Symmetree Media Association of Ontario KCWA Family & Social Services Planet in Focus International Factory Theatre Kapisanan Philippine Centre Film & Video Festival FILMI Liaison of Independent Ultra 8 Pictures Hot Docs Canadian International Filmmakers of Toronto (LIFT) Worldwide Short Film Festival Documentary Festival Malaysian Association of Canada [REE 005] Programme Inside 10/26/05 10:24 AM Page 1 elcome o he 9th nnual ~ toronto reel asian international film festival ~ MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Earlier this year an arts columnist writing in a national newspaper questioned the need for one city to mount so many niche film festivals, especially more than one with “Reel” in its name. But there’s no question in my mind about the vital role Reel Asian has played over the course of eight festivals in championing work that tends to get lost at other, bigger festivals. Exposing the local audience to films by emerging East and Southeast Asian filmmakers, particularly North American ones, has been central to Reel Asian’s programming mandate from the beginning. -

Quieting the Boom : the Shaped Sonic Boom Demonstrator and the Quest for Quiet Supersonic Flight / Lawrence R

Lawrence R. Benson Lawrence R. Benson Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Benson, Lawrence R. Quieting the boom : the shaped sonic boom demonstrator and the quest for quiet supersonic flight / Lawrence R. Benson. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Sonic boom--Research--United States--History. 2. Noise control-- Research--United States--History. 3. Supersonic planes--Research--United States--History. 4. High-speed aeronautics--Research--United States-- History. 5. Aerodynamics, Supersonic--Research--United States--History. I. Title. TL574.S55B36 2013 629.132’304--dc23 2013004829 Copyright © 2013 by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official positions of the United States Government or of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. This publication is available as a free download at http://www.nasa.gov/ebooks. ISBN 978-1-62683-004-2 90000> 9 781626 830042 Preface and Acknowledgments v Introduction: A Pelican Flies Cross Country ix Chapter 1: Making Shock Waves: The Proliferation and Testing of Sonic Booms ............................. 1 Exceeding Mach 1 A Swelling Drumbeat of Sonic Booms Preparing for an American Supersonic Transport Early Flight Testing Enter the Valkyrie and the Blackbird The National Sonic Boom Evaluation Last of the Flight Tests Chapter 2: The SST’s Sonic Boom Legacy ..................................................... 39 Wind Tunnel Experimentation Mobilizing -

Every Purchase Includes a Free Hot Drink out of Stock, but Can Re-Order New Arrival / Re-Stock

every purchase includes a free hot drink out of stock, but can re-order new arrival / re-stock VINYL PRICE 1975 - 1975 £ 22 1975 - Notes On A Conditional Form - White Vinyl £ 26 1975, The - A BRIEF INQUIRY INTO ONLINE RELATIONSHIPS (2 LP) £ 27 2 CHAINZ - Rap Or Go To The League £ 18 30 Seconds to Mars - America £ 15 50 CENT - Best Of (2 LP) £ 24 ABBA - Gold (2 LP) £ 23 ABBA - Live At Wembley Arena (3 LP) £ 38 ABBA - Super Trouper £ 20 ABBA - Voulez-Vous £ 24 AC/DC - If You Want Blood You've Got It £ 22 AC/DC - Live '92 (2 LP) £ 25 AC/DC - Live At Old Waldorf In San Francisco September 3 1977 (Red Vinyl) £ 17 AC/DC - Live In Cleveland August 22 1977 (Orange Vinyl) £ 20 AC/DC - Paradise Theater Boston August 21st 1978 (Blue Vinyl) £ 16 AC/DC - Power Up - Red Vinyl £ 31 AC/DC - Power Up - Yellow Vinyl £ 31 AC/DC - Powerage £ 23 AC/DC - The Many Faces Of (2 LP) £ 20 AC/DC Back in Black £ 23 Adele - 21 £ 19 Aerosmith - Done With Mirrors £ 25 AGNES OBEL - Myopia £ 25 Air - Moon Safari £ 26 Air - Talkie Walkie £ 20 AKERCOCKE - Renaissance In Extremis £ 19 Al Green - Let's Stay Together £ 20 Alanis Morissette - Jagged Little Pill £ 20 ALANIS MORISSETTE - Jagged Little Pill Acoustic (2 LP) £ 30 ALANIS MORISSETTE - Such Pretty Forks In The Road £ 20 ALESSIA CARA - The Pains Of Growing £ 13 ALICE COOPER - Live From The Apollo (RSD 2020) £ 39 Alice Cooper - The Many Faces Of Alice Cooper (Opaque Splatter Marble Vinyl) (2 LP) £ 21 ALICE IN CHAINS - Junkhead (Rare Tracks & TV Appearances) £ 25 Alice in Chains - Live at the Palladium, Hollywood £ 17 ALICE IN CHAINS - Live In Oakland October 8th 1992 (Green Vinyl) £ 16 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Enlightened Rogues £ 16 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Win Lose Or Draw £ 16 Altered Images - Greatest Hits £ 20 AMEDEO MINGHI / PIERO MONTANARI / ROBERTO CONRADO - Climax £ 14 Amy Winehouse - Back to Black £ 20 ANATHEMA - A Sort Of Homecoming £ 22 ANATHEMA - Eternity £ 20 Andrew W.K. -

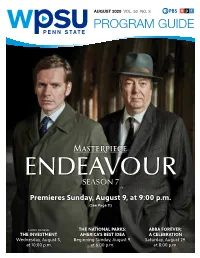

Program Guide

AUGUST 2020 VOL. 50 NO. 8 PROGRAM GUIDE ENDEAVOUR SEASON 7 Premieres Sunday, August 9, at 9:00 p.m. (See Page 11) A WPSU ORIGINAL THE NATIONAL PARKS: ABBA FOREVER: THE INVESTMENT AMERICA'S BEST IDEA A CELEBRATION Wednesday, August 5, Beginning Sunday, August 9, Saturday, August 29, at 10:00 p.m. at 6:00 p.m. at 8:00 p.m. You want your donations to WPSU to work as hard as possible. Learn more about our new Learning at Home programming at learning.wpsu.org. Starting our new fiscal year on July 1, 2020 we have made the difficult decision to revise the MONDAY – FRIDAY WPSU program guide to maintain a guide with 6:00 Ready Jet Go! television listings showing programs titles with 6:30 Arthur no descriptions, to streamline it to four pages. 7:00 Curious George This new format will begin with the September 7:30 Wild Kratts 8:00 Hero Elementary 2020 edition. 8:30 Molly of Denali This saves WPSU several thousand dollars a 9:00 Xavier Riddle and the Secret Museum year in printing costs that can be applied to 9:30 Let's Go Luna! program costs. 10:00 Daniel Tiger's Neighborhood 10:30 Daniel Tiger's Neighborhood We hope you are with us in this decision 11:00 Sesame Street toward station sustainability. We welcome 11:30 Pinkalicious & Peterrific your feedback via email at [email protected] or 12:00 Learning at Home Lineup: telephone at 814-865-3333. Check listings online at learning.wpsu.org 5:00 Odd Squad Thank you for your support.