European Commission New Regulations Concerning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

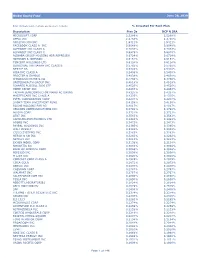

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA ACTIVIA PROPERTIES INC REIT 0.0137% 0.0137% AEON REIT INVESTMENT CORP REIT 0.0195% 0.0195% ALEXANDER + BALDWIN INC REIT 0.0118% 0.0118% ALEXANDRIA REAL ESTATE EQUIT REIT USD.01 0.0585% 0.0585% ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN GOVT STIF SSC FUND 64BA AGIS 587 0.0329% 0.0329% ALLIED PROPERTIES REAL ESTAT REIT 0.0219% 0.0219% AMERICAN CAMPUS COMMUNITIES REIT USD.01 0.0277% 0.0277% AMERICAN HOMES 4 RENT A REIT USD.01 0.0396% 0.0396% AMERICOLD REALTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0427% 0.0427% ARMADA HOFFLER PROPERTIES IN REIT USD.01 0.0124% 0.0124% AROUNDTOWN SA COMMON STOCK EUR.01 0.0248% 0.0248% ASSURA PLC REIT GBP.1 0.0319% 0.0319% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.0061% 0.0061% AZRIELI GROUP LTD COMMON STOCK ILS.1 0.0101% 0.0101% BLUEROCK RESIDENTIAL GROWTH REIT USD.01 0.0102% 0.0102% BOSTON PROPERTIES INC REIT USD.01 0.0580% 0.0580% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.0000% 0.0000% BRIXMOR PROPERTY GROUP INC REIT USD.01 0.0418% 0.0418% CA IMMOBILIEN ANLAGEN AG COMMON STOCK 0.0191% 0.0191% CAMDEN PROPERTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0394% 0.0394% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.0005% 0.0005% CAPITALAND COMMERCIAL TRUST REIT 0.0228% 0.0228% CIFI HOLDINGS GROUP CO LTD COMMON STOCK HKD.1 0.0105% 0.0105% CITY DEVELOPMENTS LTD COMMON STOCK 0.0129% 0.0129% CK ASSET HOLDINGS LTD COMMON STOCK HKD1.0 0.0378% 0.0378% COMFORIA RESIDENTIAL REIT IN REIT 0.0328% 0.0328% COUSINS PROPERTIES INC REIT USD1.0 0.0403% 0.0403% CUBESMART REIT USD.01 0.0359% 0.0359% DAIWA OFFICE INVESTMENT -

Termination Rates at European Level January 2021

BoR (21) 71 Termination rates at European level January 2021 10 June 2021 BoR (21) 71 Table of contents 1. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 2 2. Fixed networks – voice interconnection ..................................................................... 6 2.1. Assumptions made for the benchmarking ................................................................ 6 2.2. FTR benchmark .......................................................................................................... 6 2.3. Short term evolution of fixed incumbents’ FTRs (from July 2020 to January 2021) ................................................................................................................................... 9 2.4. FTR regulatory model implemented and symmetry overview ............................... 12 2.5. Number of lines and market shares ........................................................................ 13 3. Mobile networks – voice interconnection ................................................................. 14 3.1. Assumptions made for the benchmarking .............................................................. 14 3.2. Average MTR per country: rates per voice minute (as of January 2021) ............ 15 3.3. Average MTR per operator ...................................................................................... 18 3.4. Average MTR: Time series of simple average and weighted average at European level ................................................................................................................. -

Annual and Sustainability Report 2020 Content

BETTER CONNECTED LIVING ANNUAL AND SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2020 CONTENT OUR COMPANY Telia Company at a glance ...................................................... 4 2020 in brief ............................................................................ 6 Comments from the Chair ..................................................... 10 Comments from the CEO ...................................................... 12 Trends and strategy ............................................................... 14 DIRECTORS' REPORT Group development .............................................................. 20 Country development ........................................................... 38 Sustainability ........................................................................ 48 Risks and uncertainties ......................................................... 80 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Corporate Governance Statement ......................................... 90 Board of Directors .............................................................. 104 Group Executive Management ............................................ 106 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Consolidated statements of comprehensive income ........... 108 Consolidated statements of financial position ..................... 109 Consolidated statements of cash flows ............................... 110 Consolidated statements of changes in equity .................... 111 Notes to consolidated financial statements ......................... 112 Parent company income statements ................................... -

Telia Year-End Report 2000

Telia Year-End Report 2000 Telia AB (publ), SE-123 86 Farsta, Sweden Corporate Registration No. 556103-4249, Registered Office: Stockholm Telia Year-End Report 2000 Telia January–December 2000 · Strong sales in high-priority areas: Mobile Telephony +42 %, Network Wholesaling Sweden +62 %, International Carrier +32 % · The Group’s net sales totaled MSEK 54,064, an increase of 4.5 % for comparable units · The positive EBITDA trend reported in the third quarter remains unbroken. Underlying EBITDA increased by 13 % in the fourth quarter, reaching MSEK 13,087 for the full year · Operating income increased to MSEK 12,006 (MSEK 5,946) · A Letter of Intent was signed with Tele 2 concerning joint construction of the Swedish UMTS network · Letter of Intent in February 2001 on sale of the mobile operator Tess Review of Group Earnings Oct-Dec Oct-Dec Full Year Full Year MSEK 2000 1999 2000 1999 Net sales 14,540 14,887 54,064 52,121 Change in net sales (%) -2.3 7.4 3.7 5.1 Underlying EBITDA 3,790 3,343 13,087 14,059 Underlying EBITDA margin (%) 26.1 22.5 24.2 27.0 Operating income 7,930 2,505 12,006 5,946 Income after financial items 7,658 2,445 11,717 5,980 Net income 7,408 1,755 10,278 4,222 Earnings per share (SEK) 2.47 0.62 3.50 1.48 Return on equity (%) – – 23.9 14.2 Investments 10,311 4,912 47,742 12,145 of which shares and participations 3,085 1,996 8,269 4,109 Summary The Telia Group is reporting sustained robust growth in its tive prices and the high quality of the network resulted in high-priority areas. -

Global Equity Fund Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA MICROSOFT CORP

Global Equity Fund June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA MICROSOFT CORP 2.5289% 2.5289% APPLE INC 2.4756% 2.4756% AMAZON COM INC 1.9411% 1.9411% FACEBOOK CLASS A INC 0.9048% 0.9048% ALPHABET INC CLASS A 0.7033% 0.7033% ALPHABET INC CLASS C 0.6978% 0.6978% ALIBABA GROUP HOLDING ADR REPRESEN 0.6724% 0.6724% JOHNSON & JOHNSON 0.6151% 0.6151% TENCENT HOLDINGS LTD 0.6124% 0.6124% BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC CLASS B 0.5765% 0.5765% NESTLE SA 0.5428% 0.5428% VISA INC CLASS A 0.5408% 0.5408% PROCTER & GAMBLE 0.4838% 0.4838% JPMORGAN CHASE & CO 0.4730% 0.4730% UNITEDHEALTH GROUP INC 0.4619% 0.4619% ISHARES RUSSELL 3000 ETF 0.4525% 0.4525% HOME DEPOT INC 0.4463% 0.4463% TAIWAN SEMICONDUCTOR MANUFACTURING 0.4337% 0.4337% MASTERCARD INC CLASS A 0.4325% 0.4325% INTEL CORPORATION CORP 0.4207% 0.4207% SHORT-TERM INVESTMENT FUND 0.4158% 0.4158% ROCHE HOLDING PAR AG 0.4017% 0.4017% VERIZON COMMUNICATIONS INC 0.3792% 0.3792% NVIDIA CORP 0.3721% 0.3721% AT&T INC 0.3583% 0.3583% SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS LTD 0.3483% 0.3483% ADOBE INC 0.3473% 0.3473% PAYPAL HOLDINGS INC 0.3395% 0.3395% WALT DISNEY 0.3342% 0.3342% CISCO SYSTEMS INC 0.3283% 0.3283% MERCK & CO INC 0.3242% 0.3242% NETFLIX INC 0.3213% 0.3213% EXXON MOBIL CORP 0.3138% 0.3138% NOVARTIS AG 0.3084% 0.3084% BANK OF AMERICA CORP 0.3046% 0.3046% PEPSICO INC 0.3036% 0.3036% PFIZER INC 0.3020% 0.3020% COMCAST CORP CLASS A 0.2929% 0.2929% COCA-COLA 0.2872% 0.2872% ABBVIE INC 0.2870% 0.2870% CHEVRON CORP 0.2767% 0.2767% WALMART INC 0.2767% -

Digital Leaders in Norway 2019

Digital Leaders in Norway 2019 This study evaluates 78 leading Norwegian companies’ digital maturity across six dimensions: digital marketing, digital product experience, e-commerce, e-CRM, mobile and social media. It also includes a separate evaluation of 11 public organizations. www.bearingpoint.no digitalleaders.bearingpoint.com/norway Table of contents Editorial 3 Norwegian companies need Objectives and study sample 4 Research summary 6 to improve to keep up with Key findings 8 their European peers. We Digital Leaders at a glance 10 encourage them to take Dimensions of digitalization Digital marketing 14 a strategic approach to Digital product experience 16 digitalization, focus on the E-commerce 18 E-CRM 20 customer journeys and start Mobile 22 Social media 24 turning data into value. Industries Summary 28 Telecom 30 Retail 31 Food retail 32 Passenger transportation 33 Media 34 Insurance 35 TV & broadband 36 Bank 37 Energy 38 Consumer products (food) 39 Public sector Digital Leaders in Norway 2019 Purpose and selection criteria for the public sector 42 Summary of findings 44 Key findings 46 Dimensions of digitalization Digital presence 50 Digital experience 52 e-CRM 54 Mobile availability 56 Social media 58 Digital Leaders in Europe Summary 62 Top 10 European companies 64 European Digital Leaders by 66 digital dimension Summary What Norwegian companies could learn 72 from global forerunners Appendices All rankings 78 BearingPoint on digitalization 84 Authors 85 Editorial Digital leaders are customer-centric, focused on providing excellent customer journeys. They manage to turn data into value, and they have a digital leadership that ensures the right priorities, capabilities and momentum. -

Single Sector Funds Portfolio Holdings

! Mercer Funds Single Sector Funds Portfolio Holdings December 2020 welcome to brighter Mercer Australian Shares Fund Asset Name 4D MEDICAL LTD ECLIPX GROUP LIMITED OOH MEDIA LIMITED A2 MILK COMPANY ELDERS LTD OPTHEA LIMITED ABACUS PROPERTY GROUP ELECTRO OPTIC SYSTEMS HOLDINGS LTD ORICA LTD ACCENT GROUP LTD ELMO SOFTWARE LIMITED ORIGIN ENERGY LTD ADBRI LTD EMECO HOLDINGS LTD OROCOBRE LTD ADORE BEAUTY GROUP LTD EML PAYMENTS LTD ORORA LTD AFTERPAY LTD ESTIA HEALTH LIMITED OZ MINERALS LTD AGL ENERGY LTD EVENT HOSPITALITY AND ENTERTAINMENT PACT GROUP HOLDINGS LTD ALKANE RESOURCES LTD EVOLUTION MINING LTD PARADIGM BIOPHARMACEUTICALS LTD ALS LIMITED FISHER & PAYKEL HEALTHCARE CORP LTD PENDAL GROUP LTD ALTIUM LTD FLETCHER BUILDING LTD PERENTI GLOBAL LTD ALUMINA LTD FLIGHT CENTRE TRAVEL GROUP LTD PERPETUAL LTD AMA GROUP LTD FORTESCUE METALS GROUP LTD PERSEUS MINING LTD AMCOR PLC FREEDOM FOODS GROUP LIMITED PHOSLOCK ENVIRONMENTAL TECHNOLOGIES AMP LTD G8 EDUCATION LTD PILBARA MINERALS LTD AMPOL LTD GALAXY RESOURCES LTD PINNACLE INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT GRP LTD ANSELL LTD GDI PROPERTY GROUP PLATINUM INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT LTD APA GROUP GENWORTH MORTGAGE INSRNC AUSTRALIA LTD POINTSBET HOLDINGS LTD APPEN LIMITED GOLD ROAD RESOURCES LTD POLYNOVO LIMITED ARB CORPORATION GOODMAN GROUP PTY LTD PREMIER INVESTMENTS LTD ARDENT LEISURE GROUP GPT GROUP PRO MEDICUS LTD ARENA REIT GRAINCORP LTD QANTAS AIRWAYS LTD ARISTOCRAT LEISURE LTD GROWTHPOINT PROPERTIES AUSTRALIA LTD QBE INSURANCE GROUP LTD ASALEO CARE LIMITED GUD HOLDINGS LTD QUBE HOLDINGS LIMITED ASX LTD -

Press Release Template

Global Mobile Industry Leaders Commit to Accelerate 5G NR for Large-scale Trials and Deployments — Operators and technology partners to support proposal to accelerate the schedule for 3GPP 5G NR standardization to meet increasing global mobile broadband needs — — New proposal introduces an intermediate milestone to complete standardization of a variant called Non-Standalone 5G NR – BARCELONA, Spain— February 26, 2017 — Today a contingent of mobile communications companies announced their collective support for the acceleration of the 5G New Radio (NR) standardization schedule to enable large-scale trials and deployments as early as 2019. AT&T, NTT DOCOMO, INC., SK Telecom, Vodafone, Ericsson (NASDAQ:ERIC), Qualcomm Technologies, Inc., British Telecom, Telstra, Korea Telecom, Intel, LG Uplus, KDDI, LG Electronics, Telia Company, Swisscom, TIM, Etisalat Group, Huawei, Sprint, Vivo, ZTE and Deutsche Telekom will support a corresponding work plan proposal for the first phase of the 5G NR specification at the next 3GPP RAN Plenary Meeting on March 6-9 in Dubrovnik, Croatia. The first 3GPP 5G NR specification will be part of Release 15 – the global 5G standard that will make use of both sub-6 GHz and mmWave spectrum bands. Based on the current 3GPP Release 15 timeline the earliest 5G NR deployments based on standard-compliant 5G NR infrastructure and devices will likely not be possible until 2020. Instead, the new proposal introduces an intermediate milestone to complete specification documents related to a configuration called Non-Standalone 5G NR to enable large-scale trials and deployments starting in 2019. Non- Standalone 5G NR will utilize the existing LTE radio and evolved packet core network as an anchor for mobility management and coverage while adding a new 5G radio access carrier to enable certain 5G use cases starting in 2019. -

Telia Company – Annual and Sustainability Report 2019

BRINGING THE WORLD CLOSER ANNUAL AND SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 2019 CONTENT OUR COMPANY Telia Company in one minute ................................................ 4 2019 in brief ............................................................................ 6 How we create value ............................................................. 8 Comments from the CEO ..................................................... 10 Trends and strategy .............................................................. 12 DIRECTORS' REPORT Group development ............................................................. 16 Country development .......................................................... 32 Sustainability ....................................................................... 41 Risks and uncertainties ....................................................... 62 CORPORATE GOVERNANCE Corporate Governance Statement ....................................... 70 Board of Directors ............................................................... 82 Group Executive Management ............................................ 84 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Consolidated statements of comprehensive income .......... 86 Consolidated statements of financial position .................... 87 Consolidated statements of cash flows .............................. 88 Consolidated statements of changes in equity ................... 89 Notes to consolidated financial statements ........................ 90 Parent company income statements.................................. 182 Parent company -

View Annual Report

BT Group plc Annual Report & Form 20-F 2017 Welcome to BT Group plc’s Annual Report and Form-20F for 2017 Where to find more information www.btplc.com www.bt.com/annualreport Delivering our Purpose Report We’re using the power of communications to make a better world. That’s our purpose. Read our annual update. www.btplc.com/purposefulbusiness Delivering our Purpose Report Update on our progress in 2016/17 THE STRATEGIC REPORT GOVERNANCE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS ADDITIONAL INFORMATION The strategic report 2 Contents Review of the year 3 How we’re organised 8 An introduction from our Chairman 10 A message from our Chief Executive 12 This is the BT Annual Report for the year ended Operating Committee 14 31 March 2017. It complies with UK regulations Our strategy Our strategy in a nutshell 16 and comprises part of the Annual Report and How we’re doing Form 20-F for the US Securities and Exchange – Delivering great customer experience 17 – Investing for growth 18 Commission to meet US regulations. – Transforming our costs 19 Key performance indicators 20 This is the third year that we’ve applied an Our business model Integrated Reporting (IR) approach to how Our business model 22 we structure and present our Annual Report. What we do 24 Resources, relationships and sustainability IR is an initiative led by the International Integrated Reporting – Financial strength 26 Council (IIRC). Its principles and aims are consistent with UK – Our people 26 regulatory developments in financial and corporate reporting. – Our networks and physical assets 30 We’ve reflected guiding principles and content elements from the – Properties 31 IIRC’s IR Framework in preparing our Annual Report. -

Download Spotlight

SPOTLIGHT Telco Mergers and Acquisitions Strategic Backgrounds, Use Cases and Future Developments This publication or parts there of may only be reproduced or copied with the prior written permission of Detecon International GmbH. Published by Detecon International GmbH. www.detecon.com Strategic Backgrounds, Use Cases and Future Developments I Detecon SPOTLIGHT Content What is it all about? 2 Telco M&A Trends 4 Summary 14 The Authors 15 The Company 16 Footnotes 17 05/2019 1 Detecon SPOTLIGHT I Telco Mergers and Acquisitions What is it all about? For years, we at Detecon have been actively supporting our clients in acquiring and integrating other organizations within the telecommunications industry. Thereby, our consultants have been observing worldwide transaction trends and mergers & acquisitions activities (M&A) in the global telecommunication markets. This “Telco Mergers and Acquisitions Spotlight” will highlight these observations from the past year and provide strategic insights into the most recent market developments, present selected use cases and explain the underlying rationale of those mergers. Finally, it will provide an outlook for possible M&A activities in 2019 and beyond. Mergers and acquisitions can be a valuable lever in building new digital business models or facilitating digital transformation. Furthermore, they are commonly used to generate growth, create synergies and reduce risk through diversification. Hence, it is not surprising that during a time characterized by increasing market uncertainty, the year 2018 has seen fewer transactions than in previous years. However, it was a record year for high-value M&A deals which can be seen in a comparison between 2017 and 2018 (Figure 1: Average deal value ($bn), 3Q17 vs. -

Telecoms 150 2020

Telecoms 150 2020The annual report on the most valuable and strongest telecom brands April 2020 Contents. About Brand Finance 4 Get in Touch 4 Brandirectory.com 6 Brand Finance Group 6 Foreword 8 Brand Value Analysis 10 Regional Analysis 16 Brand Strength Analysis 18 Brand Finance Telecoms Infrastructure 10 20 Sector Reputation Analysis 22 Brand Finance Telecoms 150 (USD m) 24 Definitions 28 Brand Valuation Methodology 30 Market Research Methodology 31 Stakeholder Equity Measures 31 Consulting Services 32 Brand Evaluation Services 33 Communications Services 34 Brand Finance Network 36 brandirectory.com/telecoms Brand Finance Telecoms 150 April 2020 3 About Brand Finance. Brand Finance is the world's leading independent brand valuation consultancy. Request your own We bridge the gap between marketing and finance Brand Value Report Brand Finance was set up in 1996 with the aim of 'bridging the gap between marketing and finance'. For more than A Brand Value Report provides a 20 years, we have helped companies and organisations of all types to connect their brands to the bottom line. complete breakdown of the assumptions, data sources, and calculations used We quantify the financial value of brands We put 5,000 of the world’s biggest brands to the test to arrive at your brand’s value. every year. Ranking brands across all sectors and countries, we publish nearly 100 reports annually. Each report includes expert recommendations for growing brand We offer a unique combination of expertise Insight Our teams have experience across a wide range of value to drive business performance disciplines from marketing and market research, to and offers a cost-effective way to brand strategy and visual identity, to tax and accounting.