1 March 5, 2021 Re: Notice of Availability for Comment on EPA's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chlorpyrifos (Dursban) Ddvp (Dichlorvos) Diazinon Malathion Parathion

CHLORPYRIFOS (DURSBAN) DDVP (DICHLORVOS) DIAZINON MALATHION PARATHION Method no.: 62 Matrix: Air Procedure: Samples are collected by drawing known volumes of air through specially constructed glass sampling tubes, each containing a glass fiber filter and two sections of XAD-2 adsorbent. Samples are desorbed with toluene and analyzed by GC using a flame photometric detector (FPD). Recommended air volume and sampling rate: 480 L at 1.0 L/min except for Malathion 60 L at 1.0 L/min for Malathion Target concentrations: 1.0 mg/m3 (0.111 ppm) for Dichlorvos (PEL) 0.1 mg/m3 (0.008 ppm) for Diazinon (TLV) 0.2 mg/m3 (0.014 ppm) for Chlorpyrifos (TLV) 15.0 mg/m3 (1.11 ppm) for Malathion (PEL) 0.1 mg/m3 (0.008 ppm) for Parathion (PEL) Reliable quantitation limits: 0.0019 mg/m3 (0.21 ppb) for Dichlorvos (based on the RAV) 0.0030 mg/m3 (0.24 ppb) for Diazinon 0.0033 mg/m3 (0.23 ppb) for Chlorpyrifos 0.0303 mg/m3 (2.2 ppb) for Malathion 0.0031 mg/m3 (0.26 ppb) for Parathion Standard errors of estimate at the target concentration: 5.3% for Dichlorvos (Section 4.6.) 5.3% for Diazinon 5.3% for Chlorpyrifos 5.6% for Malathion 5.3% for Parathion Status of method: Evaluated method. This method has been subjected to the established evaluation procedures of the Organic Methods Evaluation Branch. Date: October 1986 Chemist: Donald Burright Organic Methods Evaluation Branch OSHA Analytical Laboratory Salt Lake City, Utah 1 of 27 T-62-FV-01-8610-M 1. -

Ambient Water Quality Criteria for Chlorpyrifos

United State. Office of Water EPA 440/5-86~05 Environmental Protection Regulations and Standards September 1986 Amy l. lea~erry Agency Criteria and Standards Division Washington DC 20460 Water &EPA Ambient Wat'er Quality Criteria for Chlorpyrifos - 1986 &~IENT AQUATIC LIFE WATER QUALITY CRITERIA FOR CHLORPYRIFOS U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY OFFICE OF RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH LABORATORIES DULUTH, MINNESOTA NARRAGANSETT, RHODE ISLAND NOTICES This document has been reviewed by the Criteria and Standards Division, Office of Water Regulations and Standards, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and approved for publication. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. This document is availaryle to the public throu~h the National Technical Inf0rmation Service (NTIS), 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, VA 22161. 11 FOREWORD Section 304(a)(1) of the Clean Water Act of 1977 (P.L. 95-217) requires the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency to publish water quality criteria that accurately reflect the latest scientific knowledge on the kind and extent of all identifiable effects on health and welfare that might be expected from the presence of pollutants in any body of water~ including ground water. This document is a revision of proposed criteria based upon consideration of comments received from other Federal agencies~ State agencies~ special interest groups~ and individual scientists. Criteria contained in this document replace any previously published EPA aquatic life criteria for the same pollutant(s). The term "water quality criteria" is used in two sections of the Clean Water Act~ section 304(a)(1) and section 303(c)(2). -

Pesticides and Toxic Substances

UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY WASHINGTON D.C., 20460 OFFICE OF PREVENTION, PESTICIDES AND TOXIC SUBSTANCES MEMORANDUM DATE: July 31, 2006 SUBJECT: Finalization of Interim Reregistration Eligibility Decisions (IREDs) and Interim Tolerance Reassessment and Risk Management Decisions (TREDs) for the Organophosphate Pesticides, and Completion of the Tolerance Reassessment and Reregistration Eligibility Process for the Organophosphate Pesticides FROM: Debra Edwards, Director Special Review and Reregistration Division Office of Pesticide Programs TO: Jim Jones, Director Office of Pesticide Programs As you know, EPA has completed its assessment of the cumulative risks from the organophosphate (OP) class of pesticides as required by the Food Quality Protection Act of 1996. In addition, the individual OPs have also been subject to review through the individual- chemical review process. The Agency’s review of individual OPs has resulted in the issuance of Interim Reregistration Eligibility Decisions (IREDs) for 22 OPs, interim Tolerance Reassessment and Risk Management Decisions (TREDs) for 8 OPs, and a Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) for one OP, malathion.1 These 31 OPs are listed in Appendix A. EPA has concluded, after completing its assessment of the cumulative risks associated with exposures to all of the OPs, that: (1) the pesticides covered by the IREDs that were pending the results of the OP cumulative assessment (listed in Attachment A) are indeed eligible for reregistration; and 1 Malathion is included in the OP cumulative assessment. However, the Agency has issued a RED for malathion, rather than an IRED, because the decision was signed on the same day as the completion of the OP cumulative assessment. -

Qsar Analysis of the Chemical Hydrolysis of Organophosphorus Pesticides in Natural Waters

QSAR ANALYSIS OF THE CHEMICAL HYDROLYSIS OF ORGANOPHOSPHORUS PESTICIDES IN NATURAL WATERS. by Kenneth K. Tanji Principal Investigator and Jonathan 1. Sullivan Graduate Research Assistant Department of Land, Air and Water Resources University of California, Davis Technical Completion Report Project Number W-843 August, 1995 University of California Water Resource Center The research leading to this report was supported by the University of California Water Resource Center as part of Water Resource Center Project W-843. Table of Contents Page Abstract 2 Problem and Research Objectives 3 Introduction 5 Theoretical Background 6 QSAR Methodology 7 Molecular Connectivity Theory 8 Organophosphorus Pesticides 12 Experimental Determination of Rates 15 Results and Discussion 17 Principal Findings and Significance 19 References 34 List of Tables Page Table 1. Statistical relationship between OP pesticides and first-order MC/'s. 30 Table 2. Inherent conditions of waters used in experimental work. 16 Table 3. Estimated half-lives for organophosphorus esters derived from model. 31 Table 4. Half-lives and first-order MCI' sfor model calibration data set. 31 Table 5. Experimental kinetic data for validation set compounds, Sacramento. 33 List of Figures Page Figure 1. Essential Features OfQSAR Modeling Methodology. 21 Figure 2. Regression plot for In hydrolysis rate vs. 1st order MCl' s. 22 Figure 3. a 3-D molecular model, a line-segment model and a graphical model. 23 Figure 4. Molecular connectivity index suborders. 24 Figure 5. Chlorpyrifos and its fourteen fourth order path/cluster fragments. 25 Figure 6. Abridged MClndex output. 26 Figure 7. Parent acids of most common organophosphorus pesticides. 12 Figure 8. -

Environmental Health Criteria 63 ORGANOPHOSPHORUS

Environmental Health Criteria 63 ORGANOPHOSPHORUS INSECTICIDES: A GENERAL INTRODUCTION Please note that the layout and pagination of this web version are not identical with the printed version. Organophophorus insecticides: a general introduction (EHC 63, 1986) INTERNATIONAL PROGRAMME ON CHEMICAL SAFETY ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH CRITERIA 63 ORGANOPHOSPHORUS INSECTICIDES: A GENERAL INTRODUCTION This report contains the collective views of an international group of experts and does not necessarily represent the decisions or the stated policy of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation, or the World Health Organization. Published under the joint sponsorship of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation, and the World Health Organization World Health Orgnization Geneva, 1986 The International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) is a joint venture of the United Nations Environment Programme, the International Labour Organisation, and the World Health Organization. The main objective of the IPCS is to carry out and disseminate evaluations of the effects of chemicals on human health and the quality of the environment. Supporting activities include the development of epidemiological, experimental laboratory, and risk-assessment methods that could produce internationally comparable results, and the development of manpower in the field of toxicology. Other activities carried out by the IPCS include the development of know-how for coping with chemical accidents, coordination -

For Aldicarb Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) Document for Aldicarb

United States Prevention, Pesticides EPA Environmental Protection and Toxic Substances September 2007 Agency (7508P) Reregistration Eligibility Decision for Aldicarb Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) Document for Aldicarb List A Case Number 0140 Approved by: Date: Steven Bradbury, Ph.D. Director Special Review and Reregistration Division Page 2 of 191 Table of Contents Aldicarb Reregistration Eligibility Decision Team ........................................................................ 5 Glossary of Terms and Abbreviations ............................................................................................ 6 Abstract........................................................................................................................................... 8 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 9 II. Chemical Overview.................................................................................................................. 11 A. Chemical Identity..................................................................................................................11 B. Regulatory History ................................................................................................................12 C. Use and Usage Profile...........................................................................................................12 D. Tolerances .............................................................................................................................13 -

Chlorpyrifos Hazards to Fish, Wildlife, and Invertebrates: a Synoptic Review

Biological Report Contaminant Hazard Reviews March 1988 Report No. 13 CHLORPYRIFOS HAZARDS TO FISH, WILDLIFE, AND INVERTEBRATES: A SYNOPTIC REVIEW By Edward W. Odenkirchen Department of Biology The American University Washington, DC 20016 And Ronald Eisler U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Patuxent Wildlife Research Center Laurel, MD 20708 SUMMARY Chlorpyrifos (phosphorothioic acid O, O,-diethyl 0-(3,5,6,-trichloro-2-pyridinyl) ester), an organophosphorus compound with an anticholinesterase mode of action, is used extensively in a variety of formulations to control a broad spectrum of agricultural and other pestiferous insects. Domestic use of chlorpyrifos in 1982 was about 3.6 million kg; the compound is used mostly in agriculture, but also to control mosquitos in wetlands (0.15 million kg applied to about 600,000 ha) and turf-destroying insects on golf courses (0.04 million kg). Accidental or careless applications of chlorpyrifos have resulted in the death of many species of nontarget organisms such as fish, aquatic invertebrates, birds, and humans. Applications at recommended rates of 0.028 to 0.056 kg/surface ha for mosquito control have produced mortality, bioaccumulation, and deleterious sublethal effects in aquatic plants, zooplankton, insects, rotifers, crustaceans, waterfowl, and fish; adverse effects were also noted in bordering invertebrate populations. Degradation rate of chloropyrifos in abiotic substrates varies, ranging from about 1 week in seawater (50% degradation) to more than 24 weeks in soils under conditions of dryness, low temperatures, reduced microbial activity, and low organic content; intermediate degradation rates reported have been 3.4 weeks for sediments and 7.6 weeks for distilled water. -

Acetylcholinesterase: the “Hub” for Neurodegenerative Diseases And

Review biomolecules Acetylcholinesterase: The “Hub” for NeurodegenerativeReview Diseases and Chemical Weapons Acetylcholinesterase: The “Hub” for Convention Neurodegenerative Diseases and Chemical WeaponsSamir F. de A. Cavalcante Convention 1,2,3,*, Alessandro B. C. Simas 2,*, Marcos C. Barcellos 1, Victor G. M. de Oliveira 1, Roberto B. Sousa 1, Paulo A. de M. Cabral 1 and Kamil Kuča 3,*and Tanos C. C. França 3,4,* Samir F. de A. Cavalcante 1,2,3,* , Alessandro B. C. Simas 2,*, Marcos C. Barcellos 1, Victor1 Institute G. M. ofde Chemical, Oliveira Biological,1, Roberto Radiological B. Sousa and1, Paulo Nuclear A. Defense de M. Cabral (IDQBRN),1, Kamil Brazilian Kuˇca Army3,* and TanosTechnological C. C. França Center3,4,* (CTEx), Avenida das Américas 28705, Rio de Janeiro 23020-470, Brazil; [email protected] (M.C.B.); [email protected] (V.G.M.d.O.); [email protected] 1 Institute of Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear Defense (IDQBRN), Brazilian Army (R.B.S.); [email protected] (P.A.d.M.C.) Technological Center (CTEx), Avenida das Américas 28705, Rio de Janeiro 23020-470, Brazil; 2 [email protected] Mors Institute of Research (M.C.B.); on Natural [email protected] Products (IPPN), Federal (V.G.M.d.O.); University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), CCS,[email protected] Bloco H, Rio de Janeiro (R.B.S.); 21941-902, [email protected] Brazil (P.A.d.M.C.) 32 DepartmentWalter Mors of Institute Chemistry, of Research Faculty of on Science, Natural Un Productsiversity (IPPN), -

United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,703,064 Yokoi Et Al

US005703064A United States Patent (19) 11 Patent Number: 5,703,064 Yokoi et al. 45) Date of Patent: Dec. 30, 1997 54 PESTICIDAL COMBINATIONS FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS 75 Inventors: Shinji Yokoi; Akira Nishida, both of 0 196524 10/1986 European Pat. Of.. Shiga-ken; Tokio Obata; Kouichi Golka, both of Ube, all of Japan OTHER PUBLICATIONS 73) Assignees: Sankyo Company, Limited, Tokyo; Worthing et al, The Pesticide Manual, 9th Ed. (1991), pp. Ube industries Ltd., Ube, both of 747 and 748. Japan L.C. Gaughan et al., "Pesticide interactions: effects of orga nophosphorus pesticides on the metabolism, toxicity, and 21 Appl. No.: 405,795 persistence of selected pyrethroid insecticides". Chemical Abstracts, vol. 94, No. 9, 1981, No. 59740k of Pestic. 22 Filed: Mar 16, 1995 Biochem. Physio., vol. 14, No. 1, 1980, pp. 81-85. 30 Foreign Application Priority Data I. Ishaaya et al., "Cypermethrin synergism by pyrethroid esterase inhibitors in adults of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci". Mar 16, 1994 JP Japan ............................ HE6045.405 Chemical Abstracts, vol. 107, No. 9, 1987, No. 72818y of (51) Int. Cl................. A01N 43/54; A01N 57/00 Pestic Biochem. Physiol., vol. 28, No. 2, 1987, pp. 155-162. 52 U.S. C. ......................................... 51480; 514/256 (58) Field of Search ..................................... 514/80, 256 Primary Examiner Allen J. Robinson Attorney, Agent, or Firm-Frishauf, Holtz, Goodman, 56 References Cited Langer & Chick, P.C. U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS 57 ABSTRACT 4,374,833 2/1983 Badmin et al. ...................... 424/225 Combinations of the known compound pyrimidifen with 4,845,097 7/1989 Matsumoto et al... 514/234.2 phosphorus-containing pesticides have a synergistic pesti 4,935,516 6/1990 Ataka et al. -

OHA 8964 Technical Report: Marijuana Contaminant Testing

TECHNICAL REPORT: OREGON HEALTH AUTHORITY’S PROCESS TO DETERMINE WHICH TYPES OF CONTAMINANTS TO TEST FOR IN CANNABIS PRODUCTS, AND LEVELS FOR ACTION Author David G. Farrer, Ph.D. Public Health Toxicologist PUBLIC HEALTH DIVISION Technical Report: Oregon Health Authority’s Process to Determine Which Types of Contaminants to Test for in Cannabis Products, and Levels for Action* Author: David G. Farrer, Ph.D., Public Health Toxicologist Acknowledgments OHA would like to thank the following individuals and organizations for their valuable contributions to the development of cannabis testing Oregon Administrative Rules (OAR 333-7-0010 through 333-7-0100 and OAR 333-7-0400 and 333-7-0410 Exhibit A) and this report: Brian Boling Rose Kachadoorian Laboratory Program Manager Oregon Department of Agriculture Oregon Department of Environmental Quality Jeremy L. Sackett Cascadia Labs, Cannabis Safety Theodore R. Bunch, Jr. Institute, and Oregon Cannabis Pesticide Analytical and Response Association Center Coordination Leader Oregon Department of Agriculture Bethany Sherman Oregon Growers Analytical and Keith Crosby Cannabis Safety Institute Technical Director Synergistic Pesticide Lab Shannon Swantek Oregon Environmental Laboratory Ric Cuchetto Accreditation Program, Public The Cannabis Chemist Health Division, Oregon Health Authority Camille Holladay Lab Director Rodger B. Voelker, Ph.D. Synergistic Pesticide Lab Lab Director Oregon Growers Analytical Mowgli Holmes, Ph.D. Phylos Bioscience and Cannabis Safety Institute For information on this report, contact David Farrer at [email protected]. * Please cite this publication as follows: Farrer DG. Technical report: Oregon Health Authority’s process to decide which types of contaminants to test for in cannabis. Oregon Health Authority. -

List of Lists

United States Office of Solid Waste EPA 550-B-10-001 Environmental Protection and Emergency Response May 2010 Agency www.epa.gov/emergencies LIST OF LISTS Consolidated List of Chemicals Subject to the Emergency Planning and Community Right- To-Know Act (EPCRA), Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) and Section 112(r) of the Clean Air Act • EPCRA Section 302 Extremely Hazardous Substances • CERCLA Hazardous Substances • EPCRA Section 313 Toxic Chemicals • CAA 112(r) Regulated Chemicals For Accidental Release Prevention Office of Emergency Management This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction................................................................................................................................................ i List of Lists – Conslidated List of Chemicals (by CAS #) Subject to the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA), Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) and Section 112(r) of the Clean Air Act ................................................. 1 Appendix A: Alphabetical Listing of Consolidated List ..................................................................... A-1 Appendix B: Radionuclides Listed Under CERCLA .......................................................................... B-1 Appendix C: RCRA Waste Streams and Unlisted Hazardous Wastes................................................ C-1 This page intentionally left blank. LIST OF LISTS Consolidated List of Chemicals -

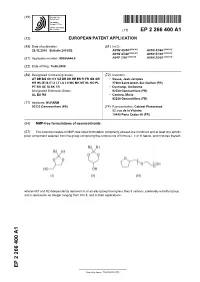

NMP-Free Formulations of Neonicotinoids

(19) & (11) EP 2 266 400 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 29.12.2010 Bulletin 2010/52 A01N 43/40 (2006.01) A01N 43/86 (2006.01) A01N 47/40 (2006.01) A01N 51/00 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 09305544.0 A01P 7/00 A01N 25/02 (22) Date of filing: 15.06.2009 (84) Designated Contracting States: (72) Inventors: AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR • Gasse, Jean-Jacques HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO PL 27600 Saint-Aubin-Sur-Gaillon (FR) PT RO SE SI SK TR • Duchamp, Guillaume Designated Extension States: 92230 Gennevilliers (FR) AL BA RS • Cantero, Maria 92230 Gennevilliers (FR) (71) Applicant: NUFARM 92233 Gennevelliers (FR) (74) Representative: Cabinet Plasseraud 52, rue de la Victoire 75440 Paris Cedex 09 (FR) (54) NMP-free formulations of neonicotinoids (57) The invention relates to NMP-free liquid formulation comprising at least one nicotinoid and at least one aprotic polar component selected from the group comprising the compounds of formula I, II or III below, and mixtures thereof, wherein R1 and R2 independently represent H or an alkyl group having less than 5 carbons, preferably a methyl group, and n represents an integer ranging from 0 to 5, and to their applications. EP 2 266 400 A1 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) EP 2 266 400 A1 Description Technical Field of the invention 5 [0001] The invention relates to novel liquid formulations of neonicotinoids and to their use for treating plants, for protecting plants from pests and/or for controlling pests infestation.