Samuel Seabury, Anglican

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samuel Seabury: First Bishop

February 8, 1940 5c a copy THE WITNESS THE SEASON OF LENT SAMUEL SEABURY: FIRST BISHOP Copyright 2020. Archives of the Episcopal Church / DFMS. Permission required for reuse and publication. SCHOOLS CLERGY NOTES SCHOOLS CARROLL, ALBERT P., a former priest of tST]t (Bencral tEijeoIogtcal the Roman Catholic Church, was admitted K e m p f r TTAIX to the ministry of the Episcopal Church on f ^em tttarg January 20th by Bishop Wing of South Florida. After a ministry of about 16 KENOSHA, WISCONSIN Three-year undergraduate years in the Roman Church he was received Episcopal Boarding and Day School. course of prescribed and elective into the communion of the Episcopal Church study. in 1937. Preparatory to all colleges. Unusual DANIELS, HENRY, Bishop of Montana, re opportunities in Art and Music. Fourth-year course for gradu ceived the degree of doctor of divinity from Complete sports program. Junior ates, offering larger opportunity Berkeley Divinity School on January 25th. School. Accredited. Address: for specialization. DAWLEY, POWEL M., is now the associate SISTERS OF ST. MARY Provision for more advanced rector of St. David’s, Roland Park, Balti more. Box W. T. work, leading to degrees of S.T.M. GARDNER, GERARD C., is now the vicar and D.Th. of Trinity Church, Fillmore, California. Kemper Hall Kenosha, Wisconsin GRAY, SIDNEY R. S., rector of several Chi ADDRESS cago parishes during his long ministry, died CATHEDRAL CHOIR SCHOOL on January 11th in his 87th year. New York City THE DEAN PFEIFFER, ROBERT F., formerly assistant A boarding school for the forty boys of Chelsea Square New York City at All Saints’, Pasadena, California, is now the Choir of the Cathedral of Saint John the the rector of Christ Church, Tacoma, Divine. -

1968 the Witness, Vol. 53, No. 19. May 9, 1968

The WITNESS MAY 9, 1968 10* publication. and Editorial reuse for The Wilderness and the City required Permission Articles DFMS. / Church The Great Forty Days John C. Leffler Episcopal the of Dealing with Conflict Archives Alfred B. Starratt 2020. Copyright NEWS: —- Rustin Sees Elections Key to Race Relations. Bishop Robinson Has Ideas on Picking Church Leaders. U.S. Problems Worry Europeans Says Visser 't Hooft SERVICES The Witness SERVICES In Leading Churches For Christ and Hit Church In Leading Churches NEW YORK CITY EDITORIAL BOARD ST. STEPHEN'S CHURCH Tenth Street, above Chestnut THB CATHEDRAL CHURCH JOHN MoGnx KBUMM, Chairman PHILADELPHIA, PBICNA. OF 8T. JOHN THB DIVINB The Rev. Alfred W. Price, D.D., Ro Sunday: Holy Communion 8, 9, 10, Morniag W. B. Sponois SB., Managing Editor The Rev. Gustav C. MecJiHng, BJ3. Prayer, Holy Communion and Sermon. 11; Minister to the Hard of Hearing Organ Recital, 3:30; Evensong, 4. EDWARD J. Mora, Editorial Assistant Sunday: 9 and 11 a.m. 7:30 p.m. Morning Prayer and Holy Communion 7:1J O. STDNBT lUan; Ln A. BSLFOBD; ROSCOB Weekdays: Mon., Tues., Wed., Thus* M, (and 10 Wed.); Evening Prayer, 3:30. 12:30 - 12:55 p.m. T. FotlBT; RlGHABD E. GABT; GOBSOIf C. Services of Spiritual Healing, Thurs. 12:30 and 5:30 p.m. THE PARISH OF TRINITY CHURCH GBAHAM; DAVID JOHNSON; HABOLD R. LAK- TRINITY CHRIST CHURCH DON LBSUB }. A. LANO; BENJAMIN Broadway & Wall St. CAMBRIDGE, MASS. Rev. John V. Butler, D.D., Rector WILLIAM STBXNOVBLLOW. Th» Rev. W. Murray Kenney, Rector Rev. Donald R. -

Founding of the Episcopal Church, Title Page

Founding of the Episcopal Church A Series of Six Articles Plus an Epilogue In the Newsletter of All Souls’ Episcopal Church, Stony Brook, NY 2007-08 Tony Knapp The text of each article is in the public domain. All rights to the illustrations are retained by the owners, who are listed in the references. Founding of the Episcopal Church, Part I Note from the Editor This is the first in a series of six articles containing some background information about the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Communion that affects Episcopalians in the United States today. The topic is the founding of the Episcopal Church, and the time period of the story is the 1770s and the 1780s. The Revolutionary War forced at least a partial cut in ties of the Church of England in the United States with that in England. The process of thereafter creating a unified Episcopal Church in the new country involved surprisingly great differences in values, differences that at times must have seemed unbridgeable. It might be tempting to think that the formation of the church government ran parallel to the formation of the civil government, but it did not. The issues were completely different. In church organization some people wanted top-down management as in Great Britain, while others wanted bottom-up management as in the theory behind the new United States. Some wanted high-church ritual, while others wanted low-church ritual. Some wanted maximum flexibility in the liturgy, while others wanted minimum flexibility. The six articles describe the process of reconciling these values. -

Who Was Bishop Samuel Seabury? by the Rev

Who was Bishop Samuel Seabury? By The Rev. Jay Cayanyang Eternal God, you blessed your servant Samuel Seabury with the gift of perseverance to renew the Anglican inheritance in North America: Grant that, joined together in unity with our bishops and nourished by your holy Sacraments, we proclaim the Gospel of redemption with apostolic zeal; through Jesus Christ, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen. Samuel Seabury was born on November 30, 1729, in North Groton, Connecticut (present day Ledyard and near Gales Ferry where Bishop Seabury Anglican Church is located). His father, also known by the same name, was the local Congregational minister. Shortly after Seabury was born, his father resigned his pastorate to pursue Holy Orders in the Church of England. While his father was away, Seabury’s mother, Abigail died. After ordination, his father returned to minister in New London, Connecticut under the banner of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts. Later, the elder Seabury remarried and moved to an assignment in Hempstead, Long Island where under his father’s tutelage as young boy, Samuel Seabury and his brother Caleb prepared for college. As such, Samuel Seabury grew up in home a life that was greatly shaped church life and the Book of Common Prayer. Samuel Seabury studied at Yale College and afterwards returned home to Long Island to study medicine and assist his father in a nearby town as a catechist. Eventually, through the encouragement and support of his father, he went on for further study in Edinburgh, Scotland. -

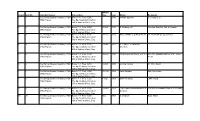

Count Item No. Calendar Header Subsection Month/ Day Year Writer Recipient 1 1 the Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- 1796) Papers

Month/ Count Item No. Calendar Header Subsection Day Year Writer Recipient 1 1 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 1740 William Spencer S. Seabury, Sr. 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 2 2 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 23-Oct 1753 S. Seabury, Sr. Thomas Sherlock, Bp. of London 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 3 3 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 24-Dec 1755 Moses Mathers & Noah Wells Dr. Bearcroft (Sec'y, S.P.G.) 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 4 4 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 23-Jan 1757 S. Clowes, Jr. and Wm. 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Sherlock Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 5 5 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 28-Feb 1757 Philip Bearcroft (Sec'y, S.P.G.) Rev. Mr. Obadiah Mather & Mr. Noah 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Wells Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 6 6 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 30-Oct 1760 Archbp. Secker Dr. Wm. Smith 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 7 7 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 16-Feb 1762 Jane Durham Mrs. Ann Hicks 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 8 8 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 4-Sep 1763 Sam'l Seabury John Troup 1796) Papers The Bp. -

Toleration and Reform: Virginia's Anglican Clergy, 1770-1776

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2009 Toleration and Reform: Virginia's Anglican Clergy, 1770-1776 Stephen M. Volpe College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons, Other Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Volpe, Stephen M., "Toleration and Reform: Virginia's Anglican Clergy, 1770-1776" (2009). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626590. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-4yj8-rx68 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Toleration and Reform: Virginia’s Anglican Clergy, 1770-1776 Stephen M. Volpe Pensacola, Florida Bachelor of Arts, University of West Florida, 2004 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History The College of William and Mary August, 2009 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts t / r ^ a — Stephen M. Volpe Approved by the Committee, July, 2009 Committee Chair Dr. Christopher Grasso, Associate Professor of History Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary ___________H h r f M ________________________ Dr. Jam es Axtell, Professor Emeritus of History Lyon Gardiner Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary X ^ —_________ Dr. -

The American Reformation: the Politics of Religious Liberty, Charleston and New York 1770-1830 by Susanna Christine Linsley

The American Reformation: The Politics of Religious Liberty, Charleston and New York 1770-1830 by Susanna Christine Linsley A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Susan M Juster, Chair Professor David J. Hancock Professor Mary C. Kelley Associate Professor Mika Lavaque-Manty Assistant Professor Daniel Ramirez © Susanna Christine Linsley 2012 Acknowledgements During one of the more challenging points in the beginning stages of the dissertation project, my advisor, Sue Juster, gave me some advice that I continue to refer to when I find myself in need of guidance. She told me that there was no secret to getting back on track. I just needed to allow myself to take some time and remember why I loved history. This observation was one of the many sage and trenchant insights Sue has offered me throughout graduate school. I cannot thank her enough for providing both such a practical and an inspiring model for scholarship. I have also been fortunate to work with a committee whose brilliance and wisdom is unmatched. Mary Kelley has been a constant source of support throughout my time in Ann Arbor. Her unfailing trust in me and in my project gave me the confidence to push my work in directions I would not have thought possible before I began. David Hancock has always asked good questions, spurring me to think deeply both about context and about broader sets of connections. His own rigorous scholarship and teaching have served as great examples to me. -

The Episcopate in America

4* 4* 4* 4 4> m amenta : : ^ s 4* 4* 4* 4 4* ^ 4* 4* 4* 4 THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES GIFT OF Commodore Byron McCandless THe. UBKARY OF THE BISHOP OF SPRINGFIELD WyTTTTTTTTTTTT*'fW CW9 M IW W W> W W W W9 M W W W in America : : fTOfffiWW>fffiWiW * T -r T T Biographical and iiogtapl)icai, of tlje Bishops of tije American Ciwrct), toitl) a l&reliminarp Cssap on tyt Historic episcopate anD 2Documentarp Annals of tlje introduction of tl)e Anglican line of succession into America William of and Otstortogmpljrr of tljr American * IW> CW tffi> W ffi> ^W ffi ^ ^ CDttfon W9 WS W fW W <W $> W IW W> W> W> W c^rtjStfan Hitetatute Co, Copyright, 1895, BY THE CHRISTIAN LITERATURE COMPANY. CONTENTS. PAGE ADVERTISEMENT vii PREFACE ix INTRODUCTION xi BIOGRAPHIES: Samuel Seabury I William White 5 Samuel Provoost 9 James Madison 1 1 Thomas John Claggett 13 Robert Smith 15 Edward Bass 17 Abraham Jarvis 19 Benjamin Moore 21 Samuel Parker 23 John Henry Hobart 25 Alexander Viets Griswold 29 Theodore Dehon 31 Richard Channing Moore 33 James Kemp 35 John Croes 37 Nathaniel Bowen 39 Philander Chase 41 Thomas Church Brownell 45 John Stark Ravenscroft 47 Henry Ustick Onderdonk 49 William Meade 51 William Murray Stone 53 Benjamin Tredwell Onderdonk 55 Levi Silliman Ives 57 John Henry Hopkins 59 Benjamin Bosworth Smith 63 Charles Pettit Mcllvaine 65 George Washington Doane 67 James Hervey Otey 69 Jackson Kemper 71 Samuel Allen McCoskry .' 73 Leonidas Polk 75 William Heathcote De Lancey 77 Christopher Edwards Gadsden 79 iii 956336 CONTENTS. -

THE FUNDAMENTALS of OUR FAITH What Is Our Story?

THE FUNDAMENTALS OF OUR FAITH What is our story? Crisis #1: Arianism and Formation of Central Christian Creeds What was at stake? Truth Main Characters? Arius, Athanasius, Emperor Constantine How will the Church ever survive? Affirming essential doctrine “Beloved, although I was very eager to write to you about our common salvation, I found it necessary to write appealing to you to contend for the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints.” (Jude 3) Crisis #2: Reformation and Persecution of Reformed English Church What was at stake? Corruption of the Church Main Characters? Martin Luther, Thomas Cranmer, Queen Mary Tudor How will the Church ever survive? A return to Biblical authority, the bold witness of martyrs “Beware of men, for they will deliver you over to courts and flog you in their synagogues, and you will be dragged before governors and kings for my sake, to bear witness before them and the Gentiles. When they deliver you over, do not be anxious how you are to speak or what you are to say, for what you are to say will be given to you in that hour. For it is not you who speak, but the Spirit of your Father speaking through you. ” (Matthew 10:17-20) Crisis #3: Founding of the Diocese of Florida What was at stake? Growth and establishment of Church in a swampy wilderness Main Characters? Bishops Rutledge, Young and Weed How will the Church ever survive? Discernment, flexibility, perseverance “Then Jesus said to his disciples, “The harvest is plentiful, but the laborers are few; therefore pray earnestly to the Lord of the harvest to send out laborers into his harvest.” (Matthew 9:37-38) 37 Martin Luther nails theses/Start of Reformation Thomas Cranmer compiles first English Book of Death of Jesus/Day of Pentecost/Birth of Church Common Prayer 33 AD 325 381 1517 1549 1556 Council of Nicaea Council of Constantinople/Completion of Nicene Creed Cranmer burns at stake under Queen Mary Tudor 38 Yellow fever strikes Jacksonville Fire destroys St. -

Bishop Samuel Seabury and the American Church

Bishop Samuel Seabury and the American Church Sermon preached by Bishop Scott McLaughlin (retired), For Independence Day, Sunday, July 8, AD 2001 Our celebration of Holy Communion this evening is in remembrance of Independence Day, and to the glory of God in honor of Samuel Seabury (November 30, 1729 – February 25, 1796), the first Bishop of the United States. Bishop Seabury’s life has a message for us today, and the week of the 4th of July is a perfect time to reflect upon the history of our Way of Faith on this continent. Before the American Revolution the Church found itself in a very difficult position. In some places, like the Carolinas and Virginia, the Church was established by law, as the State religion. Even if you weren’t a member of the Church, your taxes were spent in support of it, and to pay the salaries of its ministers. We bristle at that kind of thing today (although my tax money is spent in ways I profoundly disagree with), and the situation was not the same in other parts of the continent. People who left the Church of England, and in many cases came to America to escape State Religion settled Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Maryland, and other colonies. Those outside the Church did not necessarily believe in religious tolerance, however. The Puritans settled in New England, not because they believed in religious freedom, but because they failed in their attempt to take over the Anglican Church, and immigrated to America in order to enforce their own brand of Christianity on these shores. -

Try, Try Again

CHAPTER I Try, Try Again CoNNEcrrCUT had been who refused to pay were fined, jailed, and often founded by tough-minded roughly handled on the way to prison. Thus, Puritans who were determined what was labeled an "Act of Toleration" was the to build a new English Canaan law under which Anglicans were actually per from which Episcopacy was secute'd. Also, there were more subtle ways to to be forever excluded. And embarrass the Churchmen, for the numerous for a while it seemed as if the "public days of humiliation and prayer" fell by Congregationalist alliance be more than mere coincidence upon the great feast tween minister and magistrate days of the Christian Kalendar. Needless to say, would keep both Anglican and Anglican instruction- whether religious or secu Papist from ever gaining a lar- was discouraged. foothold in the "Land of Steady Habits." For over True, there were slight relaxations of the law half a century the Congregational Establishment during the century, but these hardly made first was not seriously challenged, but when opposi class citizens of the Anglicans. In 1727, the Angli tion finally came it was of such a nature as to cans were permitted by legislative act to pay bring violent reaction, the effects of which were the ecclesiastical taxes to the support of their own to be felt well into the nineteenth century. church. The act, however, specified that only such In 1707, the first Anglican mission was organ parishes as had a "resident minister" could claim ized in the colony, and during the next seventy the exemption and, as the S. -

Christ Church Christiana Hundred Records 2437

Christ Church Christiana Hundred records 2437 This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on September 14, 2021. Description is written in: English. Describing Archives: A Content Standard Manuscripts and Archives PO Box 3630 Wilmington, Delaware 19807 [email protected] URL: http://www.hagley.org/library Christ Church Christiana Hundred records 2437 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 4 Historical Note ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 6 Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 7 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 7 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 8 Collection Inventory ......................................................................................................................................