Lesson 4 TEB International US Territories/Possessions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OGC-98-5 U.S. Insular Areas: Application of the U.S. Constitution

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman, Committee on GAO Resources, House of Representatives November 1997 U.S. INSULAR AREAS Application of the U.S. Constitution GAO/OGC-98-5 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 Office of the General Counsel B-271897 November 7, 1997 The Honorable Don Young Chairman Committee on Resources House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: More than 4 million U.S. citizens and nationals live in insular areas1 under the jurisdiction of the United States. The Territorial Clause of the Constitution authorizes the Congress to “make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the Territory or other Property” of the United States.2 Relying on the Territorial Clause, the Congress has enacted legislation making some provisions of the Constitution explicitly applicable in the insular areas. In addition to this congressional action, courts from time to time have ruled on the application of constitutional provisions to one or more of the insular areas. You asked us to update our 1991 report to you on the applicability of provisions of the Constitution to five insular areas: Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (the CNMI), American Samoa, and Guam. You asked specifically about significant judicial and legislative developments concerning the political or tax status of these areas, as well as court decisions since our earlier report involving the applicability of constitutional provisions to these areas. We have included this information in appendix I. 1As we did in our 1991 report on this issue, Applicability of Relevant Provisions of the U.S. -

Veterinarian Shortage Situation Nomination Form

Shortage ID VMLRP USE ONLY NIFA Veterinary Medicine National Institute of Food and Agriculture Loan Repayment Program (VMLRP) US Department of Agriculture Form NIFA 2009‐0001 OMB Control No. 0524‐0050 Veterinarian Shortage Situation Expiration Date: 9/30/2019 Nomination Form To be submitted under the authority of the chief State or Insular Area Animal Health Official Veterinary Medicine Loan Repayment Program (VMLRP) This form must be used for Nomination of Veterinarian Shortage Situations to the Veterinary Medicine Loan Repayment Program (VMLRP), Authorized Under the National Veterinary Medical Service Act (NVMSA) Note: Please submit one separate nomination form for each shortage situation. See the State Animal Health Official (SAHO) section of the VMLRP web site (www.nifa.usda.gov/vmlrp) for the number of nominations permitted for your state or insular area. Location of Veterinary Shortage Area for this Nomination Location of Veterinary Shortage: (e.g., County, State/Insular Area; must be a logistically feasible veterinary practice service area) Approximate Center of Shortage Area (or Location of Position if Type III): (e.g., Address or Cross Street, Town/City, and Zip Code) Overall Priority of Shortage: ______________ Type of Veterinary Practice Area/Discipline/Specialty (select one) : ________________________________________________________________________________ For Type I or II Private Practice: Must cover(check at least one) May cover Beef Cattle Beef Cattle Dairy Cattle Dairy Cattle Swine Swine Poultry Poultry Small -

Veterinarian Shortage Situation Nomination Form

4IPSUBHF*% AK163 7.-3164&0/-: NIFAVeterinaryMedicine NationalInstituteofFoodandAgriculture LoanRepaymentProgram(VMLRP) USDepartmentofAgriculture FormNIFA2009Ͳ0001 OMBControlNo.0524Ͳ0046 VeterinarianShortageSituation ExpirationDate:11/30/2016 NominationForm Tobesubmitted undertheauthorityofthechiefStateorInsularAreaAnimalHealthOfficial VeterinaryMedicineLoanRepaymentProgram(VMLRP) ThisformmustbeusedforNominationofVeterinarianShortageSituationstotheVeterinaryMedicineLoanRepaymentProgram (VMLRP),AuthorizedUndertheNationalVeterinaryMedicalServiceAct(NVMSA) Note:Pleasesubmitoneseparatenominationformforeachshortagesituation.SeetheStateAnimalHealthOfficial(SAHO)sectionof theVMLRPwebsite(www.nifa.usda.gov/vmlrp)forthenumberofnominationspermittedforyourstateorinsulararea. LocationofVeterinaryShortageAreaforthisNomination Kenai Peninsula, Alaska LocationofVeterinaryShortage: (e.g.,County,State/InsularArea;mustbealogisticallyfeasibleveterinarypracticeservicearea) ApproximateCenterofShortageArea Kenai or Soldotna: area extends from Portage (just south of Anchorage down to (orLocationofPositionifTypeIII): Homer at the tip of the Kenai Peninsula) (e.g.,AddressorCrossStreet,Town/City,andZipCode) OverallPriorityofShortage: @@@@@@@@@@@@@@Critical Priority TypeofVeterinaryPracticeArea/Discipline/Specialty;ƐĞůĞĐƚŽŶĞͿ͗ @@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@Type II: Private Practice - Rural Area, Food Animal Medicine (awardee obligation: at least 30%@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@@ FTE or 12hr/week) &ŽƌdLJƉĞ/Žƌ//WƌŝǀĂƚĞWƌĂĐƚŝĐĞ͗ Musƚcover(checkĂtleastone) -

District of Columbia Statehood and Voting Representation

Updated June 29, 2020 District of Columbia Statehood and Voting Representation On June 26, 2020, the U.S. House of Representatives have included full statehood or more limited methods of considered and passed the Washington, D.C. Admission providing DC residents the ability to vote in congressional Act, H.R. 51. This marked the first time in 27 years a elections. Some Members of Congress have opposed these District of Columbia (DC) statehood bill was considered on legislative efforts and recommended maintaining the status the floor of the House of Representatives, and the first time quo. Past legislative proposals have generally aligned with in the history of Congress a DC statehood bill was passed one of the following five options: by either the House or the Senate. 1. a constitutional amendment to give DC residents voting representation in This In Focus discusses the political status of DC, identifies Congress; concerns regarding DC representation, describes selected issues in the statehood process, and outlines some recent 2. retrocession of the District of Columbia DC statehood or voting representation bills. It does not to Maryland; provide legal or constitutional analysis on DC statehood or 3. semi-retrocession (i.e., allowing qualified voting representation. It does not address territorial DC residents to vote in Maryland in statehood issues. For information and analysis on these and federal elections for the Maryland other issues, please refer to the CRS products listed in the congressional delegation to the House and final section. Senate); 4. statehood for the District of Columbia; District of Columbia and When ratified in 1788, the U.S. -

Environmental Assessment for the Replacement of the Pier and Boat Ramp at the U.S

Draft Environmental Assessment for the Repairs and Replacement of the Boat Ramp and Pier at the US Border Patrol Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico Environmental Assessment for the Replacement of the Pier and Boat Ramp at the U.S. Border Patrol & Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico U.S. Customs and Border Protection February 2019 Draft Environmental Assessment for the Repairs and Replacement of the Boat Ramp and Pier at the US Border Patrol Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico Environmental Assessment for the Replacement of the Pier and Boat Ramp at the U.S. Border Patrol & Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico Environmental Assessment for the Replacement of the Pier and Boat Ramp at the U.S. Border Patrol & Air and Marine Facility, Ponce, Puerto Rico Lead Agency: U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Proposed Action: The demolition and removal of the temporary structure, removal of the original pier, construction of a new pier, and replacement of the boat ramp at 41 Bonaire Street in the municipality of Ponce, Puerto Rico. The replacement boat ramp would be constructed in the same location as the existing boat ramp, and the pier would be constructed south of the Ponce Marine Unit facility. For Further Information: Joseph Zidron Real Estate and Environmental Branch Chief Border Patrol & Air and Marine Program Management Office 24000 Avila Road, Suite 5020 Laguna Niguel, CA 92677 [email protected] Date: February 2019 Abstract: CBP proposes to remove the original concrete pier, demolish and remove the temporary structure, construct a new pier, replace the existing boat ramp, and continue operation and maintenance at its Ponce Marine Unit facility at 41 Bonaire Street, Ponce, Puerto Rico. -

Ruling America's Colonies: the Insular Cases Juan R

YALE LAW & POLICY REVIEW Ruling America's Colonies: The Insular Cases Juan R. Torruella* INTRODUCTION .................................................................. 58 I. THE HISTORICAL BACKDROP TO THE INSULAR CASES..................................-59 11. THE INSULAR CASES ARE DECIDED ......................................... 65 III. LIFE AFTER THE INSULAR CASES.......................... .................. 74 A. Colonialism 1o ......................................................... 74 B. The Grinding Stone Keeps Grinding........... ....... ......................... 74 C. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and President Taft ................. 75 D. The Jones Act of 1917, U.S. Citizenship, and ChiefJustice Taft ............ 77 E. Local Self-Government v. Colonial Status...........................79 IV. WHY THE UNITED STATES-PUERTO Rico RELATIONSHIP IS COLONIAL...... 81 A. The PoliticalManifestations of Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......82 B. The Economic Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's ColonialRelationship.....82 C. The Cultural Manifestationsof Puerto Rico's Colonial Relationship.......89 V. THE COLONIAL STATUS OF PUERTO Rico Is UNAUTHORIZED BY THE CONSTITUTION AND CONTRAVENES THE LAW OF THE LAND AS MANIFESTED IN BINDING TREATIES ENTERED INTO BY THE UNITED STATES ............................................................. 92 CONCLUSION .................................................................... 94 * Judge, United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. The substance of this Article was presented in -

Testimony Medicaid and CHIP in the U.S. Territories

Statement of Anne L. Schwartz, PhD Executive Director Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission Before the Health Subcommittee Committee on Energy and Commerce U.S. House of Representatives March 17, 2021 i Summary Medicaid and CHIP play a vital role in providing access to health services for low-income individuals in the five U.S. territories: American Samoa, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The territories face similar issues to those in the states: populations with significant health care needs, an insufficient number of providers, and constraints on local resources. With some exceptions, they operate under similar federal rules and are subject to oversight by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. However, the financing structure for Medicaid in the territories differs from state programs in two key respects. First, territorial Medicaid programs are constrained by an annual ceiling on federal financial participation, referred to as the Section 1108 cap or allotment (§1108(g) of the Social Security Act). Territories receive a set amount of federal funding each year regardless of changes in enrollment and use of services. In comparison, states receive federal matching funds for each state dollar spent with no cap. Second, the federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) is statutorily set at 55 percent rather than being based on per capita income. If it were set using the state formula, the matching rate for all five territories would be significantly higher, and for most, would likely be the maximum of 83 percent. These two policies have resulted in chronic underfunding of Medicaid in the territories, requiring Congress to step in at multiple points to provide additional resources. -

Excavations at Maruca, a Preceramic Site in Southern Puerto Rico

EXCAVATIONS AT MARUCA, A PRECERAMIC SITE IN SOUTHERN PUERTO RICO Miguel Rodríguez ABSTRACT A recent set of radiocarbon dated shows that the Maruca site, a preceramic site located in the southern coastal plains of Puerto Rico, was inhabited between 5,000 and 3,000 B.P. bearing the earliest dates for human habitation in Puerto Rico. Also the discovery in the site of possible postmolds, lithic and shell workshop areas and at least eleven human burials strongly indicate the possibility of a permanent habitation site. RESUME Recientes fechados indican una antigüedad entre 5,000 a 3000 años antes de del presente para Maruca, una comunidad Arcaica en la costa sur de Puerto Rico. Estos son al momento los fechados más antiguos para la vida humana en Puerto Rico. El descubrimiento de socos, de posible talleres líticos, de áreas procesamiento de moluscos y por lo menos once (11) enterramientos humanos sugieren la posibilidad de que Maruca sea un lugar habitation con cierta permanence. KEY WORDS: Human Remains, Marjuca Site, Preceramic Workshop. INTRODUCTION During the 1980s archaeological research in Puerto Rico focused on long term multidisciplinary projects in early ceramic sites such as Sorcé/La Hueca, Maisabel and Punta Candelera. This research significantly expanded our knowledge of the life ways and adaptive strategies of Cedrosan and Huecan Saladoid cultures. Although the interest in these early ceramic cultures has not declined, it seems that during the 1990s, archaeological research began to develop other areas of interest. With the discovery of new preceramic sites of the Archaic age found during construction projects, the attention of specialists has again been focused on the first in habitants of Puerto Rico. -

Puerto Rico, Colonialism In

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive Latin American, Caribbean, and U.S. Latino Latin American, Caribbean, and U.S. Latino Studies Faculty Scholarship Studies 2005 Puerto Rico, Colonialism In Pedro Caban University at Albany, State Univeristy of New York, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/lacs_fac_scholar Part of the Latin American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Caban, Pedro, "Puerto Rico, Colonialism In" (2005). Latin American, Caribbean, and U.S. Latino Studies Faculty Scholarship. 19. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/lacs_fac_scholar/19 This Encyclopedia Entry is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin American, Caribbean, and U.S. Latino Studies at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Latin American, Caribbean, and U.S. Latino Studies Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 516 PUERTO RICO, COLONIALISM IN PUERTO RICO, COLONIALISM IN. Puerto Rico They automatically became subjects of the United States has been a colonial possession of the United States since without any constitutionally protected rights. Despite the 1898. What makes Puerto Rico a colony? The simple an humiliation of being denied any involvement in fateful swer is that its people lack sovereignty and are denied the decisions in Paris, most Puerto Ricans welcomed U.S. fundamental right to freely govern themselves. The U.S. sovereignty, believing that under the presumed enlight Congress exercises unrestricted and unilateral powers over ened tutelage of the United States their long history of Puerto Rico, although the residents of Puerto Rico do not colonial rule would soon come to an end. -

Tribal and Insular Area Grants: Diesel Emissions Reduction Act (DERA) Request for Applications

&EPA United States Office of Transportation and Air Quality Environmental Protection March 2021 Agency Coming Soon: Tribal and Insular Area Grants: Diesel Emissions Reduction Act (DERA) Request for Applications Request for Application (RFA) opens late April 2021 The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is excited to announce plans to request applications for projects that achieve significant reductions in diesel emissions. EPA anticipates awarding approximately $5 million in total DERA funding and plans to have no mandatory cost share requirement for projects. Eligible Organizations Eligible entities include tribal governments (or intertribal consortia) and Alaska Native villages, or insular area government agencies which have jurisdiction over transportation or air quality. Insular areas include the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, American Samoa, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. 2021 Tribal and Insular Area RFA Highlights TRIBAL GOVERNMENTS (OR INTERTRIBAL INSULAR AREA GOVERNMENTS CONSORTIA) AND ALASKA NATIVE VILLAGES • Approximately $4.5 Million • Approximately $500,000 • Funding Limit per Application: $800,000 • Funding Limit per Application: $250,000 • Two Applications per Applicant • Two Applications per Applicant Although funding for both tribes and insular areas is planned under this single RFA, the applications will be competed separately. Tribal and insular area applications will be reviewed, ranked, and selected by separate review panels. Anticipated Timeline and Dates Description Date* RFA Opens Late April, 2021 Informational Webinars EPA will host three webinars to accommodate the different time zones and schedules RFA Closes – Applications Due Early July, 2021 Anticipated Notification of Selection Mid August, 2021 Anticipated Award October-December 2021 *Finalized dates will be posted online at www.epa.gov/dera when the RFA officially opens. -

Establishment of the Public Archives of Hawaii As a Territorial Agency

Establishment of the Public Archives of Hawaii as a Territorial Agency By CHESTER RAYMOND YOUNG Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/30/1/67/2744960/aarc_30_1_xq4852040p211x1u.pdf by guest on 25 September 2021 Vanderbilt University T THE Honolulu office of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, on January 26, 1903, William DeWitt Alexander A received a caller from Washington, D.C. This stranger was Worthington C. Ford, Chief of the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, then on his way to Manila to inspect the archives of the Philippine Islands. Listed as bound for Hong Kong, Ford had arrived in port the preceding afternoon aboard the liner Korea of the Pacific Mail Steamship Co., less than 5 days out of San Francisco.1 Doubtless he called on Alexander as the corre- sponding secretary of the Hawaiian Historical Society and the leading Hawaiian historian of his day. In his diary Alexander recorded the visit with this brief note: "Mr. W. C. Ford of the Congressional Library called, to inquire about the Govt Archives."2 Ford learned that the records of the defunct Kingdom of Hawaii were for the most part in Honolulu in various government buildings, particularly in Iolani Palace, which served as the Territorial Capitol. The Secretary of Hawaii was charged with the duty of keeping the legislative and diplomatic archives of the Kingdom, but his custody of them was only legal and perfunctory, with little or no attention given to their preserva- tion. Other records of the monarchy officials were in the care of their successors under the Territory of Hawaii. -

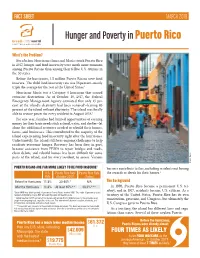

Hunger and Poverty in Puerto Rico

FACT SHEET MARCH 2019 Hunger and Poverty in Puerto Rico What’s the Problem? Even before Hurricanes Irma and Maria struck Puerto Rico in 2017, hunger and food insecurity were much more common among Puerto Ricans than among their fellow U.S. citizens in the 50 states. Before the hurricanes, 1.5 million Puerto Ricans were food insecure. The child food insecurity rate was 56 percent—nearly triple the average for the rest of the United States.1 Hurricane Maria was a Category 4 hurricane that caused extensive destruction. As of October 10, 2017, the Federal Emergency Management Agency estimated that only 15 per- cent of the island’s electricity had been restored2—leaving 85 percent of the island without electricity. The island was finally able to restore power for every resident in August 2018.3 For one year, families had limited opportunities of earning money for their basic needs such as food, water, and shelter—let alone the additional resources needed to rebuild their homes, farms, and businesses. This contributed to the majority of the island experiencing food insecurity right after the hurricanes. Unfortunately, the island still faces ongoing challenges to help residents overcome hunger. Recovery has been slow, in part, because assistance from FEMA to repair bridges and roads, clean debris, and rebuild homes has been difficult for some parts of the island, and for every resident, to access. Various iStock photo 5 PUERTO RICANS ARE FAR MORE LIKELY TO BE FOOD INSECURE barriers contribute to this, including residents not having U.S. Puerto Rico Rate Puerto Rico Rate the records or deeds for their homes.4 Rate (October 2017) (Today) Before the Hurricanes 11.8% 30-60%* N/A The Background After the Hurricanes 11.8% At least 85%** 38.3%*** In 1898, Puerto Rico became a permanent U.S.