Japan and Multilateralism in Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

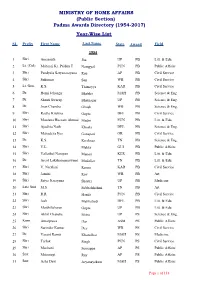

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Download Report [PDF

This Annual Report can also be accessed at website: www.meaindia.nic.in Front Cover: Illustration of Central Secretariat buildings from water colour painting by Shri Kashi Nath Das Designed and produced by: CYBERART INFORMATIONS PVT. LTD. Kanu Chambers, 3rd Floor, C-2, Sanwal Nagar, New Delhi 110 049, INDIA Telefax: 26256148/26250700 E mail:[email protected] Contents Introduction 1 Highlights of the Year 2 Synopsis 4 1. Indias Neighbours n Thailand 43 n Morocco 59 n Afghanistan 11 PMs Visit and Agreement for 44 n Palestine 59 n Bangladesh 12 Bilateral FTA n Sudan 60 n Bhutan 14 n Timor Leste 45 n Syria 60 Military Operation in Bhutan 14 n Vietnam 45 n Tunisia 60 by Royal Bhutanese Army China 15 n 3. East Asia 6. Africa (South of Sahara) PMs visit to China, 15 n Japan 46 n Angola 61 22-27 June 2003 n Republic of Korea (ROK) 47 n Botswana 61 n Hongkong 22 n Democratic Peoples Republic 49 n Namibia 61 n Iran 22 of Korea (DPRK) n Zambia 61 President Khatamis Visit and 22 n Mongolia 49 n Mozambique 62 The New Delhi Declaration n Swaziland 62 n Maldives 24 4. Central Asia n South Africa 62 n Myanmar 24 n Azerbaijan 50 n Lesotho 65 n Nepal 27 n Kazakhstan 50 n Zimbabwe 65 Maoist Insurgency in Nepal 27 n Kyrghyzstan 50 n Ethiopia 65 n Pakistan 28 n Tajikistan 51 n Madagascar 65 PMs Initiative at 28 n Turkey 51 n Tanzania 65 Srinagar, 18 April 2003 n Turkmenistan 52 n Zanzibar 66 Indian proposals to Pakistan: 28 n Uzbekistan 52 n Uganda 66 22 October 2003 n Rwanda 66 Ceasefire along the 30 5. -

Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving?

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Fuchs, Andreas; Richert, Katharina Working Paper Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving? Discussion Paper Series, No. 604 Provided in Cooperation with: Alfred Weber Institute, Department of Economics, University of Heidelberg Suggested Citation: Fuchs, Andreas; Richert, Katharina (2015) : Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving?, Discussion Paper Series, No. 604, University of Heidelberg, Department of Economics, Heidelberg, http://dx.doi.org/10.11588/heidok.00019769 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/127421 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von -

ASEAN's Perceptions of Japan: Change and Continuity

ASEAN’s PERCEPTIONS OF JAPAN Change and Continuity Bhubhindar Singh Introduction Relations between the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and Japan have long been influenced by the events of World War Two (WWII). Japan’s wartime actions, which entailed rapacious resource exploitation and grave atrocities, are still fresh in the minds of many Southeast Asians. This historical memory has colored the perceptions of ASEAN people about the kind of role Japan could play in ASEAN affairs during the post-war period. Such perceptions have especially blocked Ja- pan’s participation in the political/security affairs of ASEAN. Although ASEAN has gradually welcomed Japan into its economic sphere, it has gen- erally rejected Japan’s involvement in its political affairs. Robert O. Tilman has captured this divide in ASEAN’s perceptions of Japan in his works, which are among the most influential on this subject. 1 Tilman wrote, “. it is obvious that trade balances and strategic political thinking do not have a one-to-one correspondence.”2 This paper aims to develop Tilman’s argument on ASEAN’s perceptions of Japan. It identifies two distinct attitudes in these perceptions. First, as argued by Tilman, ASEAN countries’ perceptions of Japan tend to differ on issues relating to the economic or political/security spheres. While Japan’s Bhubindar Singh is Associate Research Fellow at the Institute of De- fence and Strategic Studies, Singapore. Asian Survey , 42:2, pp. 276–296. ISSN: 0004–4687 2002 by The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Send Requests for Permission to Reprint to: Rights and Permissions, University of California Press, Journals Division, 2000 Center St., Ste. -

The Middle East

F THE MIDDLE EAST F THE MIDDLE EAST (a) Overview Ensuring stability and prosperity in Afghanistan is essential in realizing peace, stability and prosperity in The Middle East is a region with a long history, where the region. It is also very important from the viewpoint different ethnic groups and religions coexist. Since the of eradicating and preventing terrorism and stopping the terrorist attacks in the United States (US), there has been flow of drugs. Reconstruction assistance provided to a renewed focus on the threat of terrorism and the prolif- Afghanistan could become a prime example of efforts eration of weapons of mass destruction (WMDs) and toward the “consolidation of peace,” whereby assistance their delivery vehicles as particularly grave issues in the is provided so that a country which has ended a long- Middle East. At the same time, conflicts based on ethnic term conflict does not fall again into the vicious cycle of and religious differences still continue. Ensuring peace starting another conflict and becoming a collapsed and stability in this region has become a major challenge country. As a responsible member of the international in realizing peace, stability and prosperity for the entire community, Japan plans to continue making active international community, including Japan. In addition, contributions toward the reconstruction of Afghanistan. because Japan relies on this region for over 80% of its energy resources, the Middle East is vitally important in (b) Iraq ensuring a stable, long-term supply of energy to Japan. With this awareness, Japan has been actively involved in In 2002, the suspicion over Iraq’s possession and devel- working to bring about peace and stability in the entire opment of WMDs and their delivery vehicles once again Middle East region, as well as strengthening relations attracted major attention in the international community. -

Japan's Evolving Interests in Multilateral Security Cooperation In

Japan’s Evolving Interests in Multilateral Security Cooperation in the Asia-Pacific: A Two-Dimensional Approach Based on the assessment of security environment and unique characteristics of the Asia-Pacific region, the most recent Diplomatic Bluebook of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) of Japan articulates that “the most realistic and appropriate approaches for the enhancement of the region’s security environment should be viewed as developing and strengthening both bilateral and multilateral frameworks for dialogue and cooperation in a multi-tiered manner.”1 Since the end of World War II, the fundamental pillar of Japan’s security policy has been and continues to be its bilateral alliance with the United States. This was explicitly confirmed by Prime Minister Hashimoto and President Clinton in the April 1996 Japan-U.S. Joint Declaration on Security. Tokyo’s favourable reference to multilateral security cooperation is relatively a new development. This paper examines the evolution of Japanese policies on multilateral security cooperation in the Asia-Pacific Region. Multilateralism and Asia-Pacific in Japan’s Policy The term regional multilateral security cooperation contains at least two different aspects, namely ‘regional’ and ‘multilateral’. This requires us to look at Japan’s policy from the two dimensions: functional and geopolitical. Simply put, the term ‘multilateral’ suggests functional dimension whereas the term ‘regional’ suggests geopolitical dimension. Multilateralism: Functional Dimension Even though MOFA’s first Diplomatic Bluebook published in 1957 enunciated the UN-centred diplomacy as one of the three principles of the keynote of Japan’s diplomacy, the basis of Japanese foreign and security policy has been far from UN-centred or multilateral. -

Explaining the Dispatch of Japan's Self- Defense

LEARNING HOW TO SWEAT: EXPLAINING THE DISPATCH OF JAPAN’S SELF- DEFENSE FORCES IN THE GULF WAR AND IRAQ WAR By Jeffrey Wayne Hornung A Dissertation Submitted To The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences Of the George Washington University In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 31, 2009 Dissertation directed by Mike Mochizuki Associate Professor of Political Science and International Affairs The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Jeffrey Wayne Hornung has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of July 13, 2009. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. LEARNING HOW TO SWEAT: EXPLAINING THE DISPATCH OF JAPAN’S SELF- DEFENSE FORCES IN THE GULF WAR AND IRAQ WAR Jeffrey Wayne Hornung Dissertation Research Committee: Mike Mochizuki , Associate Professor of Political Science and International Affairs Dissertation Director James Goldgeier , Professor of Political Science and International Affairs Committee Member Deborah Avant , Professor of Political Science, University of California-Irvine Committee Member ii © Copyright 2009 by Jeffrey Wayne Hornung All rights reserved iii To Maki Without your tireless support and understanding, this project would not have happened. iv Acknowledgements This work is the product of four years of research, writing and revisions. Its completion would not have been possible without the intellectual and emotional support of many individuals. There are several groups of people in particular that I would like to mention. First and foremost are two individuals who have had the greatest impact on my intellect regarding Japan: Nat Thayer and Mike Mochizuki. -

Postwar Japan: Growth, Security, and Uncertainty Since 1945

EDITORS Michael J. Green Zack Cooper POSTWAR JAPAN Growth, Security, and Uncertainty since 1945 hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh Postwar Japan —-1 —0 —+1 594-67311_ch00_3P.indd 1 12/20/16 4:45 PM hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh -1— 0— +1— 594-67311_ch00_3P.indd 2 12/20/16 4:45 PM hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh Postwar Japan Growth, Security, and Uncertainty since 1945 Editors Michael J. Green Zack Cooper ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London —-1 —0 —+1 594-67311_ch00_3P.indd 3 12/20/16 4:45 PM hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh hn hk io il sy SY ek eh Center for Strategic & International Studies 1616 Rhode Island Ave nue, NW Washington, DC 20036 202-887-0200 | www . csis . org Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, MD 20706 w w w . r o w m a n . c o m Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2017 by the Center for Strategic & International Studies All rights reserved. -

University of London Japan's Security Policy and The

University of London Japan’s Security Policy and the ASEAN Regional Forum: The Search for Multilateral Security in the Asia Pacific Takeshi YUZA WA London School of Economics and Political Science Department of International Relations A thesis submitted to the University of London for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Relations 2005 UMI Number: U61BB59 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U613359 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 1 ! Lid*-»y British i_itx»ry ot noiiticai and Eoonomic Science iHc Sfc S F Abstract This thesis explores changes in Japan’s conception of and policy toward security multilateralism in the Asia-Pacific region after the end of the Cold War with special reference to the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF). To understand the complex processes behind the changes in and formation of these perceptions, this study develops an eclectic analysis, which draws on the insights of various theoretical models in International Relations (IR). Based on a persistent analysis of Japan’s diplomacy in security institution building over the decade, this study goes on not only to illuminate the problems and the direction of Japan’s post-Cold War security policy but also to provide an empirical basis for examining the validity of three theoretical perspectives on the role and efficacies of security institutions, namely realism, neoliberal institutionalism and constructivism. -

Paper Development Ministers 37

University of Heidelberg Department of Economics Discussion Paper Series No. 604 Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving? Andreas Fuchs and Katharina Richert November 2015 Do Development Minister Characteristics Affect Aid Giving?* ANDREAS FUCHS, Heidelberg University, Germany KATHARINA RICHERT#, Heidelberg University, Germany This version: November 2015 Abstract: Over 300 government members have had the main responsibility for international development cooperation in 23 member countries of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee since the organization started reporting detailed Official Development Assistance (ODA) data in 1967. Understanding their role in foreign aid giving is crucial since their decisions might directly impact aid effectiveness and thus economic development on the ground. Our study examines whether development ministers’ personal characteristics influence aid budgets and aid quality. To this end, we create a novel database on development ministers’ gender, political ideology, prior professional experience in development cooperation, education in economics, and time in office over the 1967- 2012 period. Results from fixed-effects panel regressions show that some of the personal characteristics of development ministers matter. Most notably, we find that more experienced ministers with respect to their time in office obtain larger aid budgets. Moreover, there is evidence that female ministers as well as officeholders with prior professional experience in development cooperation and a longer time in office provide higher-quality ODA. JEL classification: D78, F35, H11, O19 Keywords: development minister, leadership, foreign aid, Official Development Assistance, aid budget, aid quality, personal characteristics, gender, partisan politics, experience 1 * We are grateful for valuable comments by Axel Dreher, Pierre-Guillaume Méon, Sarmistha Pal, Francisco J. -

(1954-2014) Year-Wise List 1954

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2014) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs 3 Shri Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Venkata 4 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 5 Shri Nandlal Bose PV WB Art 6 Dr. Zakir Husain PV AP Public Affairs 7 Shri Bal Gangadhar Kher PV MAH Public Affairs 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh PB WB Science & 14 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta PB DEL Civil Service 15 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service 17 Shri Amarnath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. 21 May 2014 Page 1 of 193 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field 18 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & 19 Dr. K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & 20 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmad 21 Shri Josh Malihabadi PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs 23 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. 24 Dr. Arcot Mudaliar PB TN Litt. & Edu. Lakshamanaswami 25 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PB PUN Public Affairs 26 Shri V. Narahari Raooo PB KAR Civil Service 27 Shri Pandyala Rau PB AP Civil Service Satyanarayana 28 Shri Jamini Roy PB WB Art 29 Shri Sukumar Sen PB WB Civil Service 30 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri PB UP Medicine 31 Late Smt. -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2017) Year-Wise List SL Prefix First Name Last Name State Award Field 1954 1 Shri Amarnath Jha UP PB Litt. & Edu. 2 Lt. (Col) Maharaj Kr. Palden T Namgyal PUN PB Public Affairs 3 Shri Pandyala Satyanarayana Rau AP PB Civil Service 4 Shri Sukumar Sen WB PB Civil Service 5 Lt. Gen. K.S. Thimayya KAR PB Civil Service 6 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha MAH PB Science & Eng. 7 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar UP PB Science & Eng. 8 Dr. Jnan Chandra Ghosh WB PB Science & Eng. 9 Shri Radha Krishna Gupta DEL PB Civil Service 10 Shri Moulana Hussain Ahmad Madni PUN PB Litt. & Edu. 11 Shri Ajudhia Nath Khosla DEL PB Science & Eng. 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati OR PB Civil Service 13 Dr. K.S. Krishnan TN PB Science & Eng. 14 Shri V.L. Mehta GUJ PB Public Affairs 15 Shri Vallathol Narayan Menon KER PB Litt. & Edu. 16 Dr. Arcot Lakshamanaswami Mudaliar TN PB Litt. & Edu. 17 Shri V. Narahari Raooo KAR PB Civil Service 18 Shri Jamini Roy WB PB Art 19 Shri Satya Narayana Shastri UP PB Medicine 20 Late Smt. M.S. Subbalakshmi TN PB Art 21 Shri R.R. Handa PUN PB Civil Service 22 Shri Josh Malihabadi DEL PB Litt. & Edu. 23 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta UP PB Litt. & Edu. 24 Shri Akhil Chandra Mitra UP PS Science & Eng. 25 Kum. Amalprava Das ASM PS Public Affairs 26 Shri Surinder Kumar Dey WB PS Civil Service 27 Dr. Vasant Ramji Khanolkar MAH PS Medicine 28 Shri Tarlok Singh PUN PS Civil Service 29 Shri Machani Somappa AP PS Public Affairs 30 Smt.