Un Centrism in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peace in Vietnam! Beheiren: Transnational Activism and Gi Movement in Postwar Japan 1965-1974

PEACE IN VIETNAM! BEHEIREN: TRANSNATIONAL ACTIVISM AND GI MOVEMENT IN POSTWAR JAPAN 1965-1974 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE AUGUST 2018 By Noriko Shiratori Dissertation Committee: Ehito Kimura, Chairperson James Dator Manfred Steger Maya Soetoro-Ng Patricia Steinhoff Keywords: Beheiren, transnational activism, anti-Vietnam War movement, deserter, GI movement, postwar Japan DEDICATION To my late father, Yasuo Shiratori Born and raised in Nihonbashi, the heart of Tokyo, I have unforgettable scenes that are deeply branded in my heart. In every alley of Ueno station, one of the main train stations in Tokyo, there were always groups of former war prisoners held in Siberia, still wearing their tattered uniforms and playing accordion, chanting, and panhandling. Many of them had lost their limbs and eyes and made a horrifying, yet curious, spectacle. As a little child, I could not help but ask my father “Who are they?” That was the beginning of a long dialogue about war between the two of us. That image has remained deep in my heart up to this day with the sorrowful sound of accordions. My father had just started work at an electrical laboratory at the University of Tokyo when he found he had been drafted into the imperial military and would be sent to China to work on electrical communications. He was 21 years old. His most trusted professor held a secret meeting in the basement of the university with the newest crop of drafted young men and told them, “Japan is engaging in an impossible war that we will never win. -

The Interpreter

Japan: grasping for hope in a new imperial era | The Interpreter https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/japan-grasping-hope-ne... Tets Kimura Japan has three New Year’s Days this year. 1 January, the calendar new year was the obvious beginning, then followed 1 April, the start of the financial and academic year that is famously symbolised by seasonal cherry blossoms – and now 1 May, the once-only celebration of the first day of what will be known as the Reiwa era of imperial reign. The transition from the current Heisei era to the next era of Reiwa will occur as the Reigning Emperor has decided to abdicate his position to the Crown Prince, even though this was not constitutionally permissible. No Emperor has stepped down from the position in Japan in the last 200 years, but it was the Emperor’s wish to do so as he found it difficult to be responsible in his role at his age. He is 85. Tuesday will be his last day as the Emperor, and under the “one generation, one title” rule, the era of Heisei will consequently end. According to the newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun, 58% of Japanese think Japan will move to a better direction in the new era of Reiwa, whereas 17% see a negative future. The current era of Heisei started on 8 January 1989, a day after the Showa Emperor passed away. When the dramatic Showa era (1926-1989) ended, a time in which Japan experienced wars, the Allied Occupation, and the rapid post- Second World War recovery, Japan decided to name the following imperial reign period Heisei. -

Collecting Karamono Kodō 唐物古銅 in Meiji Japan: Archaistic Chinese Bronzes in the Chiossone Museum, Genoa, Italy

Transcultural Perspectives 4/2020 - 1 Gonatella Failla "ollecting karamono kod( 唐物古銅 in Mei3i Japan: Archaistic Chinese 4ronzes in the Chiossone Museum, Genoa, Ital* Introduction public in the special e>hibition 7ood for the The Museum of Oriental Art, enoa, holds the Ancestors, 7lo#ers for the ods: Transformations of !apanese and Chinese art collections #hich Edoardo Archaistic 4ronzes in China and !apan01 The e>hibits Chiossone % enoa 1833-T()*( 1898) -athered during #ere organised in 5ve main cate-ories: archaistic his t#enty-three-year sta* in !apan, from !anuary copies and imitations of archaic ritual 2ronzes; 1875 until his death in April 1898. A distinguished 4uddhist ritual altar sets in archaistic styleC )aramono professor of design and engraving techniques, )od( hanaike, i.e0 Chinese @o#er 2ronzes collected in Chiossone #as hired 2* the Meiji -overnment to !apan; Chinese 2ronzes for the scholar’s studioC install modern machinery and esta2lish industrial !apan’s reinvention of Chinese archaismB 2ronze and production procedures at the Imperial Printing iron for chanoyu %tea ceremony), for 2unjincha %tea of 4ureau, T()*(, to instruct the youn- -eneration of the literati,, and for @o#er arrangement in the formal designers and engravers, and to produce securit* rik)a style0 printed products such as 2anknotes, state 2ond 4esides documenting the a-es-old, multifaceted certificates, monopoly and posta-e stamps. He #as interest of China in its o#n antiquit* and its unceasing #ell-)no#n also as a portraitist of contemporaneous revivals, the Chiossone 2ronze collection attests to historic 5-ures, most nota2ly Philipp-7ranz von the !apanese tradition of -athering Chinese 2ronzes 9ie2old %1796-1866, and Emperor Meiji %1852-1912, r. -

2019 Undergraduate/Graduate Schools Academic Affairs Handbook

2019 Undergraduate/Graduate Schools Academic Affairs Handbook Center for Academic Affairs Bureau of Academic Affairs, Sophia University When the Public Transportation is shutdown When the university decides that is it not possible to hold regular classes or final exams due to the shutdown of transport services caused by natural disasters such as typhoons, heavy rainfall, accidents or strikes, classes may be canceled and exams rescheduled to another day. Such cancellation and changes will be announced on the university’s official website, Loyola, official Facebook, or Twitter. Offices Related to Academic Affairs The phone numbers listed are extension numbers. Dial 03-3238-刊刊刊刊 (extension number) when calling from an external line. Office Main work handled Location Ext. Affairs related to classes, class cancellations, make-up 1st floor, Bldg. 2 3515 Center for classes, examinations, grading, etc. Academic Affairs Teacher's Lounge 2nd floor, Bldg. 2 3164 Office of Mejiro Mejiro Seibo Campus, 6151 Regarding Mejiro Seibo Campus Seibo Campus 1st floor,Bldg.1 03-3950-6151 Center for Teaching and Affairs related to subjects for the teaching license course and 2nd floor, Bldg. 2 3520 Curator curator license course Credentials Affairs related to loaning of equipment and articles, lost and Office of found, application for use of meeting rooms, etc. 1st floor, Bldg. 2 3112 Property Management of Supply Room (Service hours 8:15䡚19:40) Supply Room Service hours 8:15䡚17:50 1st floor, Bldg. 11 4195 ICT Office Use of COM/CALL rooms, SI room and consultation related 3rd floor, Bldg. 2 3101 (Media Center) to the use of computers Reading and loaning 3510 Library Academic information (Reserve book system) 1st floor, Bldg. -

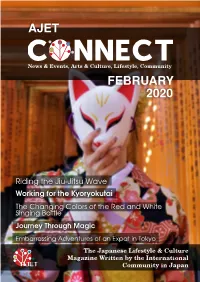

February 2020 Ajet

AJET News & Events, Arts & Culture, Lifestyle, Community FEBRUARY 2020 Riding the Jiu-Jitsu Wave Working for the Kyoryokutai The Changing Colors of the Red and White Singing Battle Journey Through Magic Embarrassing Adventures of an Expat in Tokyo The Japanese Lifestyle & Culture Magazine Written by the International Community in Japan1 In response to ongoing global news, the team at Connect Magazine would like to acknowledge the devastating impact of the 2019-2020 bushfires in Australia. Our thoughts and support are with those suffering. 2 Since September 2019, the raging fires across the eastern and southeastern Australian coastal regions have burned over 17.9 million acres, destroyed over 2000 homes, and killed least 27 people. A billion animals have been caught in the fires, with some species now pushed to the brink of extinction. Skies are reddened from air heavy with smoke— smoke which can be seen 2,000km away in New Zealand and even from Chile, South America, which is more than 11,000km away. Currently, massive efforts are being taken to tackle the bushfires and protect people, animals, and homes in the vicinity. If you would like to be a part of this effort, here are some resources you can use to help: Country Fire Authority Country Fire Service Foundation In Victoria In South Australia New South Wales Rural The Australian Red Cross Fire Service Fire recovery and relief fund World Wildlife Fund GIVIT Caring for injured wildlife and Donating items requested by habitat restoration those affected The Animal Rescue Collective Craft Guild Making bedding and bandaging for injured animals. -

The Cartographic Heritage of Tokyo: the Representation of Urban Landscapes on Maps from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries

J-READING JOURNAL OF RESEARCH AND DIDACTICS IN GEOGRAPHY 2, 9, December, 2020, pp. 115-125 DOI: 10.4458/3617-10 The Cartographic Heritage of Tokyo: The Representation of Urban Landscapes on Maps from the Seventeenth to Nineteenth Centuries Shinobu Komeiea a Department of Geography, Hosei University, Tokyo, Japan Email: [email protected] Received: August 2020 – Accepted: October 2020 Abstract This study presents an overview of the history of maps depicting Tokyo (Edo) published from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries. Of these maps, the main emphasis is given to Edo Kiriezu, sectional maps of Edo; these maps are used to determine the ways people were conscious of their city, and also to discuss past geographical thought. Here, an investigation is made of the cityscape characteristics of Edo as depicted on old maps. The study concludes that the urban landscape of Edo as depicted in Edo Kiriezu is the terminal point for considering what kind of spatial awareness “Edoites” had of the places where they lived. The Edo cityscape depicted in these maps has also served modern Tokyo as an important tool for recollecting and understanding Edo. Not only do maps of Edo help us to reconstruct lost urban landscapes, they also function as our cartographic heritage and illuminate the geographic thought of people who came before. Keywords: Cartographic Heritage, Edo, Edoites, Geographical Thought, Landscape, Map Publication 1. Introduction Tokyo, which was the name that replaced Edo). Thus, from the Meiji period on, Tokyo served as For this study, specific maps of Tokyo from the imperial capital; many people came to live in the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries were Tokyo, and the city was progressively selected. -

A Comparative Study Between the Book Thief and Grave of the Fireflies from the Perspective of Trauma Narratives

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 10, No. 7, pp. 785-790, July 2020 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1007.09 Who has Stolen Their Childhood?—A Comparative Study Between The Book Thief and Grave of the Fireflies from the Perspective of Trauma Narratives Manli Peng University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, China Yan Hua University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, China Abstract—Literature from the perspective of perpetrators receives less attention due to history and ethical problems, but it is our duty to view history as a whole. By comparing and analyzing The Book Thief and Grave of the Fireflies, this study claims that war and blind patriotism have stolen the childhood from the war-stricken children and that love, care, company and chances to speak out the pain can be the treatments. In the study, traumatic narratives, traumatic elements and treatments in both books are discussed comparatively and respectively. Index Terms—The Book Thief, Grave of the Fireflies, traumatic narratives, traumatic elements, treatments I. INTRODUCTION Markus Zusak's novel The Book Thief relates how Liesel Meminger, a little German girl, lost her beloved ones during the Second World War and how she overcame her miseries with love, friendship and the power of words. But The Book Thief is not just a Bildungsroman. According to Zusak, the inspiration of the book came from his parents, who witnessed a collection of Jews on their way to the death camps and the streetscape of Hamburg after the firebombing. The story “depicts the traumatic life experience of the German civilians and the hiding life of a Jew in the harsh situation of racial discrimination”(Chen, 2016, p. -

Public Safety/Service Minutes

CITY COUNCIL MINUTES September 23, 2019 The meeting was called to order by Mayor Rausch at 7:00 p.m. The pledge of allegiance was led by Mayor Rausch. The invocation was given by Mayor Rausch. MEMBERS PRESENT: Nevin Taylor, Deborah Groat, Scott Brock, J.R. Rausch, Alan Seymour, Mark Reams, and Henk Berbee. OTHERS PRESENT: City Manager Terry Emery, Police Chief Floyd Golden, Finance Director Justin Nahvi, Law Director Tim Aslaner, Fire Chief Jay Riley, Public Service Director Mike Andrako, City Engineer Jeremy Hoyt, City Planner Ashley Gaver, Zoning Administrator Ron Todd, Clerk of Council Rebecca Dible, Journal Tribune Mac Cordell, Bobb Alloway, Chad Wolniewicz, Connie Godwin, Paul Lazenby, Scott Zwiezinski, Josh Bochkor, Tony Eufinger, Ginger Turner, Vanessa Martin, Jason Martin, Steve Legron, Tracey Legron, Karen Legron, Vanessa Prentice, Matthew Legron, Jouanna Howard, Billie Hinkle, Craig Nicol, Jason Stanford, Mike Lynch, Michelle Anderson, Debbie Meadows, Mela Kircher, Jason Willis, Jermaine Ferguson. APPROVAL OF MINUTES: Mrs. Groat moved to approve the September 9, 2019 minutes as presented; affirmative voice vote was unanimous. APPOINTMENT: Mr. Taylor moved to appoint Chad Wolniewicz to the Planning Commission. Affirmative voice vote was unanimous. Mr. Emery appointed Chad Wolniewicz to the Design Review Board. LEFT BLANK INTENTIONALLY 1 | Page Mayor Rausch gave the following: PROCLAMATION: Whereas, suicide is the tenth leading cause of death in Ohio claiming the lives of over 47,000 people; and Whereas, on average, one person -

11. Comparative Law

DEVELOPMENTS IN 2009 ― ACADEMIC SOCIETIES 109 (10)“Global Risk and the World Order” Hirohide Takigawa(Professor, Osaka City University) (11)“Comment” Taku Morimoto(Lecturer, Health Sciences University of Hokkaido) (12)“Symposium: The Risk Society and Law” 11. Comparative Law I. The Japan Society of Comparative Law held its 72nd General Meeting at Kanagawa University on June 6 and 7, 2009. First Day 1. Anglo-American Law Section: (1)“The Principle of Good Faith in American Law” Yuko Funakoshi(Lecturer, Okinawa International University). (2)“Function and Significance of Protective Order in the Discovery” Harumi Takebe(Doctral Course, Kwansei Gakuin University). (3)“Legal Policy for Brown Field Problems in America ― Comparison between Federal Law and California State Law and its Indications for Japan” Kumiko Fukuda(Doctral Course, Waseda University). 2. Continental Law Section: (1)“Neues Kaufgewahrleistungsrecht und Wahlrecht des Insolvenzverwalters” Koichi Tamura(Associate Professor, Kumamoto University). (2)“Des restitutions en droit civil français” Tetsushi Saito(Associate Professor, Hokkaido University). 3. Socialist Law Section: (1)“Trail for Khmer Rouge and the Future Tasks of Cambodian Judicial System” Kuong Teilee(Associate Professor, Nagoya University). 110 WASEDA BULLETIN OF COMPARATIVE LAW Vol. 29 (2)“The Relationship between International Covenants on Human Rights and Domestic Law in China” Tetsuya Ouchi(Lecturer, Hokuriku University). 4.Mini-Symposium A: “Reference and Invocation of Foreign Law and International Law in the Supreme Court of the United States” (1)“Introduction” Shigeo Miyagawa(Professor, Waseda University). (2)“Significance of Reference to Foreign Laws at the Constitutional Judgment in Capital Punishment ― With Roper v. Simmons(2005)as a Starting Point” Takuya Katsuta(Associate Professor, Osaka City University). -

Homosexuality and Manliness in Postwar Japan

Homosexuality and Manliness in Postwar Japan Japan’s first professionally produced, commercially marketed and nationally distributed gay lifestyle magazine, Barazoku (‘The Rose Tribes’), was launched in 1971. Publicly declaring the beauty and normality of homosexual desire, Barazoku electrified the male homosexual world whilst scandalizing mainstream society, and sparked a vibrant period of activity that saw the establishment of an enduring Japanese media form, the homo magazine. Using a detailed account of the formative years of the homo magazine genre in the 1970s as the basis for a wider history of men, this book examines the rela- tionship between male homosexuality and conceptions of manliness in postwar Japan. The book charts the development of notions of masculinity and homo- sexual identity across the postwar period, analysing key issues including public/ private homosexualities, inter-racial desire, male–male sex, love and friendship; the masculine body; and manly identity. The book investigates the phenomenon of ‘manly homosexuality’, little treated in both masculinity and gay studies on Japan, arguing that desires and individual narratives were constructed within (and not necessarily outside of) the dominant narratives of the nation, manliness and Japanese culture. Overall, this book offers a wide-ranging appraisal of homosexuality and manliness in postwar Japan, that provokes insights into conceptions of Japanese masculinity in general. Jonathan D. Mackintosh is Lecturer in Japanese Studies at Birkbeck, University of London, -

Introduction: Protesting National Identity

Introduction: Protesting national identity In 1968 and the early months of 1969 anti-Vietnam War activists gathered in the underground passageways of Shinjuku Station on a Saturday night to sing folk songs and listen to antiwar speeches. With a name that made it sound like a cross between a renegade force and a hippy movement, the Tokyo Folk Guerilla concerts saw as many as 7000 activists crowding into the underground plaza and surrounding passageways. 1 Held in a subway station below one of Tokyo’s burgeoning city centres, the concerts were in many ways an underground movement of student sects and activists embracing images from the American civil rights movement. On the other hand, with Shinjuku being one of the world’s biggest and busiest train stations the Folk Guerilla activists were coming into contact with millions of commuters from all over Japan. Shinjuku was the point of intersection between activists and the ‘ordinary people’ converging on Tokyo. In a slight metaphorical twist the protest went underground at Shinjuku in an endeavour to be inclusive and representative, to bring ‘the people’ of Japan into contact with political activism. ‘Everybody sing together,’ read one pamphlet distributed around the newly ordained ‘citizens plaza,’ ‘Sing for the protection of fundamental human rights - for freedom of thought and freedom of expression.’ 2 There was a sense of both hope and urgency underpinning the gatherings, as underground activists sought to excavate new sites for popular political expression. Far from being marginal or illicit, the activist politics implicit in the Folk Guerilla concerts were integral to the opportunity and economic prosperity that surfaced in 1960s Japan. -

The 21 Biennale of Sydney (2018) Announces First 21 Artists for Its 45

MEDIA RELEASE Embargoed until 5pm Thursday, 6 April 2017 The 21st Biennale of Sydney (2018) announces first 21 artists for its 45th anniversary exhibition Mit Jai Inn, Junta Monochrome #1, 2016, oil on canvas. 800 x 800 x 50 cm. Courtesy the artist; Gallery Ver, Bangkok; and Cartel Artspace, Bangkok Photograph: Jirat Ratthawongjirakul Sydney, Australia: Mami Kataoka, Artistic Director of the 21st Biennale of Sydney, today revealed the first group of 21 artists selected for the 21st edition of the Asia Pacific’s leading contemporary art event. With around 70 artists expected to be included in the 21st Biennale, this initial selection includes internationally renowned artists Ai Weiwei, Laurent Grasso, Haegue Yang and Eija-Liisa Ahtila, and provides insight into the themes of the 2018 edition. Celebrating its 45th anniversary next year, the Biennale of Sydney will be presented over twelve weeks from Friday, 16 March until Monday, 11 June 2018 (Preview 13-15 March), at multiple locations throughout Sydney. It will feature major new commissions and recent work by contemporary artists from Australia and around the world. The 21 artists announced today as part of the first reveal include one artist duo, ten artists from throughout Asia, five European artists, four Australian artists and one artist from North America. The initial list of artists is as follows: • Eija-Liisa Ahtila (Born 1959 in Finland, lives and works in Helsinki) • Ai Weiwei (Born 1957 in China, lives and works in Beijing) • Brook Andrew (Born 1970 in Australia, lives and works in Melbourne) • Oliver Beer (Born 1985 in England, lives and works in Paris and London) • Anya Gallaccio (Born 1963 in Scotland, lives and works in San Diego) • Laurent Grasso (Born 1972 in France, lives and works in Paris and New York) • N.S.