"Other" in V. S. Naipaul's "A House for Mr. Biswas"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representation of Postcolonial Identity in Naipaul's Works

Vol. 4(10), pp. 451-455, December, 2013 DOI: 10.5897/IJEL2013.0481 International Journal of English and Literature ISSN 2141-2626 ©2013 Academic Journals http://www.academicjournals.org/IJEL Review Representation of postcolonial identity in Naipaul's works Bijender Singh V.P.O. Jagsi, Tehsil Gohana, District Sonepat, Haryana, India. Accepted 29 July, 2013 This paper attempts to explore representation of postcolonial identity in V. S. Naipaul’s three works A House for Mr. Biswas, A Bend in the River and An Enigma of Arrival. This paper attempts to relate how these three works are replete with the theme of identity as the chief protagonists of all these three novels hanker after to find a place for them in the world to assert their identities. Their minds vacillate between two contradictory cultures existing in that time. Researcher attempts to analyze the different strands of identity to make the work more comprehensive and to radicalize its global demand. The origin of the word ‘identity’ and its literary importance has been projected through this paper along with the different meanings of identity having a slight difference in their meaning. Postcolonial Diasporic authors and their works have been mentioned in the paper to carry out further research on the theme of postcolonial identity. V. S. Naipaul’s earned vacuity of female authors by challenging them and their rabble-rousing strengthened his identity in the world, has been assessed and analyzed. It has been studied how in these three novels, main protagonists try to claim their place in the world that is full of challenges in their real life and consequently, the environment of these novels poses a cultural-clash to make their journey of life more complicated and hard to live in antagonistic surroundings. -

V. S. Naipaul's a House for Mr Biswas: a Satire on Hinduism

V. S. NAIPAUL’S A HOUSE FOR MR BISWAS: A SATIRE ON HINDUISM Bijender Singh Research Scholar Dravidian University, Kuppam Andhra Pradesh, India Abstract Present paper is an attempt to explore how V.S. Naipaul’s novel A House for Mr Biswas is a satire on Hindu customs, traditions, rituals and rites. Naipaul’s novels are about his peregrination of orthodoxies prevalent in Hinduism. Through the paper the researcher tries to highlight that some Hindu Brahmins of high society claim themselves of supreme caste but their actions are inferior even to those people who are considered from the lowest stratum of society. They claim with proud to be Brahmins and follow the Hindu rituals blindly but they have no any quest for religion, salvation, sacrifice or goodness. They follow the Hindu rituals impassively because their ancestors did so. But they defy and infringe all rules and customs of the Hindu religion whenever the rituals come on their way. Hindus are famous for vegetarianism and their love for Hindu religious books. But in this novel they discard all rules to grind their own axes and follow the western culture blindly. These Hindus don’t refrain even from eating meat whereas even the egg is not touched in Hindu families. Such kind of themes have been projected and studied extensively in this paper. Key-Words: Hinduism, Traditions, Rituals, Post-Colony, Satire, Humanity. V. S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr. Biswas is a story of Indian Hindu migrants whose grand-parents have been migrated in Trinidad and Tobago as indentured labourers on the sugarcane estates and started living there permanently. -

IDENTITY and HOME in THREE CARIBBEAN AUTHORS By

IDENTITY AND HOME IN THREE CARIBBEAN AUTHORS By HARBHAJAN S. HIRA Bachelor of Science Guru Nanak Dev University Amritsar, Punjab (India) 1974 Master of Arts in English Hamburg University Hamburg, Germany 1987 Master of Arts in English California State University, Stanislaus Turlock, California 2001 Master of Arts in Education California State University, Dominguez Hills Carson, California 2007 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY July, 2020 IDENTITY AND HOME IN THREE CARIBBEAN AUTHORS Dissertation Approved: Dr. Timothy Murphy Dissertation Adviser Dr. Katherine Hallemeier Dr. Martin Wallen Dr. Alyson Greiner ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Several persons have helped making this project successful. My thanks go to Dr. Katherine Hallemeier, who provided feedback with an unprecedented speed in the final weeks of writing. Thanks are due to Professor Emeritus Martin Wallen as well. In spite of his retirement in 2019, Dr. Wallen kindly agreed to stay on the committee and help me get across the finish line. I also enormously benefited from his course on species, race, and surveillance, where I first discussed theorists such as Du Bois and Fanon. I want to thank Dr. Alyson Greiner of Geography too, who provided all the support that can be expected of an outside committee member. A big THANK YOU goes to Dr. Timothy Murphy, however. As my advisor and chair of the committee, he has been instrumental in securing the success of the project. He meticulously read and commented on every single chapter over the past year and a half. -

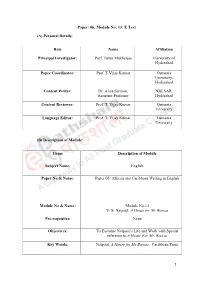

Paper: 06; Module No: 13: E Text

Paper: 06; Module No: 13: E Text (A) Personal Details: Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee University of Hyderabad Paper Coordinator: Prof. T Vijay Kumar Osmania University, Hyderabad Content Writer: Dr. Alice Samson, NALSAR, Assistant Professor Hyderabad Content Reviewer: Prof. T. Vijay Kumar Osmania University Language Editor: Prof. T. Vijay Kumar Osmania University (B) Description of Module: Items Description of Module Subject Name: English Paper No & Name: Paper 06: African and Caribbean Writing in English Module No & Name: Module No.13 V. S. Naipaul: A House for Mr Biswas V. S. Naipaul: A House for Mr Biswas Pre-requisites: None Objectives: To Examine Naipaul’s Life and Work with Special reference to A House For Mr. Biswas Key Words: Naipaul, A House for Mr Biswas, Caribbean Prose 1 Summary: The lesson, through a reading of the novel A House for Mr. Biswas, introduces the reader to the life and works of Sir V.S. Naipaul. It contextualises the novel, discusses the plot, the main characters and the main themes that are addressed in the novel. Module-I: Introduction to A House for Mr. Biswas Listed amongst the 100 best novels written in English language in the twentieth century, V.S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr. Biswas is one of the most significant novels to have been written by a Caribbean author. The novel describes the travails of the protagonist Mohun Biswas, who seeks to own a house in Trinidad. The novel is set in the first half of the twentieth century. Even as the novel depicts the desires and insecurities of Mohun, it rather humorously depicts the lives of the various members of the gregarious Tulsi household. -

Writing-A-House-For-Mr.-Biswas.Pdf

The New York Review of Books Writing 'A House for Mr. Biswas' By V. S. Naipaul Of all my books A House for Mr. Biswas is the one closest to me. It is the most personal, created out of what I saw and felt as a child. It also contains, I believe, some of my funniest writing. I began as a comic writer and still consider myself one. In middle age now, I have no higher literary ambition than to write a piece of comedy that might complement or match this early book. The book took three years to write. It felt like a career; and there was a short period, toward the end of the writing, when I do believe I knew all or much of the book by heart. The labor ended; the book began to recede. And I found that I was unwilling to reenter the world I had created, unwilling to expose myself again to the emotions that lay below the comedy. I became nervous of the book. I haven't read it since I passed the proofs in May 1961. My first direct contact with the book since the proofreading came two years ago, in 1981. I was in Cyprus, in the house of a friend. Late one evening the radio was turned on, to the BBC World Service. I was expecting a news bulletin. Instead, an installment of my book was announced. The previous year the book had been serialized on the BBC in England as "A Book at Bedtime." The serialization was now being repeated on the World Service. -

Appendix A: Naipaul's Family, a House for Mr Biswas and the Mimic

Appendix A: Naipaul’s Family, A House for Mr Biswas and The Mimic Men Naipaul’s fiction makes imaginative use of actual people. His father Seepersad (1906–53) is the model for Mr Biswas. After Seepersad’s father died when he was six years old, Seepersad and his impoverished mother became dependent on his mother’s sister (Tara of Biswas) and her wealthy husband (Ajodha) who owned rum shops, taxis and other busi- nesses. After some schooling Seepersad became a sign-painter; he painted a sign for the general store connected to Lion House (Hanuman House in Biswas) owned by the Capildeos (the Tulsis) of Chaguanas and married Bropatie Capildeo (Shama). Although his seven children were born in Lion House he usually resided elsewhere. After he had painted advertising signs for the Trinidad Guardian (the Sentinel in Biswas), the editor allowed him to submit articles, then hired him as a reporter. As Seepersad had a highly developed sense of humour his reports and interviews made him well known. After several moves Seepersad became the newspaper’s Chaguanas correspondent but lived by himself in a wooden house away from Lion House until he had a mental collapse – possibly influenced by his resig- nation from the paper after the editor had been fired and its policy changed, and possibly by a fierce quarrel with the very orthodox Hindu Capildeos about religious reform. After his nervous breakdown he became an overseer on a Capildeo estate (Green Vale) and then a shopkeeper (The Chase). He rejoined the Guardian, and moved to Port of Spain where for ten years he lived in various houses owned by the Capildeos before acquiring his own house (the Sikkim Street house). -

A House for Mr. Biswas: a Chronicle of a Man’S Search for Identity

www.ijcrt.org © 2021 IJCRT | Volume 9, Issue 4 April 2021 | ISSN: 2320-2882 A House for Mr. Biswas: A Chronicle of a Man’s Search for Identity Moirangthem Dolly M.A. (English), UGC-NET, B.Ed. Abstract:- In 1961, Naipaul published his fourth novel, A House for Mr. Biswas, regarded by many critics as one of the best novels in English fiction. The story of the protagonist, Mohun Biswas captures authentic West- Indian life, but it also transcends provincial boundaries and suggests concepts which are universal in their human implications. Mr. Biswas’ desperate struggle to acquire a “house” of his own is symbolic of an individual’s need to develop an authentic identity. This novel marks the climax of the early phase of Naipaul’s artistic development. A House for Mr. Biswas is a tragic comic novel set in Trinidad in 1950s. This paper highlights the chronicle of a man’s search for identity through the character of its protagonist Mr. Biswas. Keywords:- authentic identity, transcends, West-Indian life, fiction. Introduction:- Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul was born on 17th August, 1932 in West Indian Trinidad. He is regarded as the mouthpiece of displacement and rootlessness by critics and scholars. He is a novelist, a travel-writer, and an essayist. It was Naipaul’s father who provided him the first models for the literary and journalistic interests. His novels are mainly light, satirical comedies, some centred on politics and elections, some on frustrated meaningless life of urban poverty. He was awarded the Booker Prize in the year 1971, the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2001. -

The 100 Caribbean Books That Made Us

The 100 Caribbean Books That Made Us The Bocas Lit Fest turned to their social media channels to attempt to answer the question: what might a Caribbean list of 100 defining reads look like? The result is 100 Caribbean Books That Made Us - an unranked, expansive list as wide-ranging as the Caribbean Sea and its diaspora, spanning multiple genres, generations, styles, languages, settings and themes – a timeless reading list for the Caribbean reader, by the Caribbean reader. Inside these book covers are a range of concerns – class division, colourism, colonialism, development, exile, belonging, identity formation, and love and the challenges of love. www.bocaslitfest.com/books-that-made-us The majority of these titles are available for loan and can be reserved free of charge on our online catalogue: https://capitadiscovery.co.uk/islington If you are not already a library member you can join to borrow books and other items, as well as use eBooks, eAudiobooks, online magazines, newspapers, comics and other online resources. You can join online at: h ttps://www.islington.gov.uk/libraries-arts-and-heritage/libraries / join-islington-libraries by emailing [email protected] or phoning 020 7527 6952 @Islingtonlibs @IslingtonLibraries Michael Anthony Green Days by the River Fiction A coming of age story about Shell, who quickly matures against the backdrop of lush Mayaro village life and learns about love, friendship and responsibility. Michael Anthony The Year in San Fernando Fiction Twelve year old Francis goes to work as a servant companion in the city of San Fernando, where he learns lessons that change his outlook on love, hope and death. -

A House for Mr Biswas: Picador Classic Free Download

A HOUSE FOR MR BISWAS: PICADOR CLASSIC FREE DOWNLOAD V. S. Naipaul | 640 pages | 28 Nov 2016 | Pan MacMillan | 9781509803507 | English | London, United Kingdom A House for Mr Biswas: (Picador Classic) At the end, the only thought that remains in my mind, is to never repeat the same mistakes as Mr. He was struck again and again by the wonder of being in his own house, the audacity of it: to walk in through his own front gate, to bar entry to whoever he wished, to close his doors and windows every night. Naipaul Author. All in all, it is the story of the life of Mr. But when he marries into the domineering Tulsi family on whom he indignantly becomes dependent, Mr. Other than this, you will enjoy the unique prose language of V. One person found this helpful. Among the Believers. I will not read another by Naipaul, Nobel laureate or not. Moving from the A House for Mr Biswas: Picador Classic, Mr Biswas and Shama find that they cannot move out as they had moved in, with a donkey cart. Click here to purchase from Rakuten Kobo. Biswas has been told since the day of his birth that misfortune will follow him - and so it has. Your browser is currently not set to accept cookies. A schoolboy is rarely singled out from his siblings and mates in this way, much less a babe in arms. But his determined efforts have met only with calamity. The Nightwatchman's Occurrence. Naipaul is a great writer Add To List. Please update your browser or enable Javascript to allow our site to run correctly. -

A Postcolonial Survey Of" a House for Mr. Biswas" by VS Naipaul

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 6 No. 4; August 2015 Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Australian International Academic Centre, Australia A Postcolonial Survey of “A House for Mr. Biswas” by V. S. Naipaul Bahareh Shojaan Faculty of Foreign Languages, Department of English Literature Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.4p.72 Received: 19/03/2015 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.4p.72 Accepted: 28/05/2015 Abstract The present study tries to apply the postcolonial approach to V.S. Naipaul's A House for Mr. Biswas. It has been tried to investigate what happens to the people of other nations immigrating to a creole society.In this novel by Naipaul, the writer draws our attention to the characters who are immigrant Indian people spending their lives in the creole society of Trinidad under the dominance of colonial power. By studying the three generations of Indian in this novel we can observe how the characters of the novel change their identity, religion, education, customs, etc. as a result of living in the creole society. It is seen that as the generation changes the belief of the characters on their original culture fades away and they merge into the colonial power. The characters in the novel, when encountering the colonizer's culture, change their identity and become who they want them to be. Moreover, during the course of the novel, the characters find ambivalent personality as a result of experiencing unhomliness in the society of mixed cultures. -

The Strange Luck of V.S. Naipaul

The Strange Luck of V.S. Naipaul Directed by ADAM LOW Produced by MARTIN ROSENBAUM Executive Producer ANTHONY WALL A LONE STAR PRODUCTION for BBC FOUR ARENA: THE STRANGE LUCK OF V.S. NAIPAUL ‘No-one comes close to V.S. Naipaul. He has reached such a pitch of authority that even if you disagree with what he is saying, you have to acknowledge his intellect and astonishing mastery of style’ - Philip Hensher in the Guardian’s recent survey of the greatest living writers in English. This is the first time that Sir Vidia Naipaul has agreed to a comprehensive documentary being made about his life and work. He has not been the subject of a film of any kind for almost twenty years - long before he was knighted (1992) and awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature (2001) – so this is a unique opportunity to get close to our greatest living novelist. “I could never become vain, because I know there’s been a large element of luck – but probably everyone has these bits of luck in his life, don’t you think? Everyone who does something, who achieves something, has had his own stations of luck. It’s not all a Calvary.” Arena: The Strange Luck of V.S. Naipaul interweaves the strands of his life in the three most significant places in his experience as a writer: Trinidad, India and Wiltshire. Trinidad In May 2007, Naipaul made his first visit for over a decade to Trinidad, the island where he was born and grew up, but which he has since dismissed as a “plantation society”. -

Alienation and Rootlessness in the Novels of V.S. Naipaul

Volume II Issue I, April 2014 ISSN 2321 - 7065 Alienation and Rootlessness in the Novels of V.S. Naipaul Dr. Sneh Gupta Research Holder Mjp RohilKhand University Bareilly (U.P) Abstract Displacement and complexities prevalent in the life of expatriates have emerged as a major theme in the 20th century authors crossing the barriers of caste, creed and nationality. It has become a universal phenomenon. Modern literature abounds in alienated individuals. It reflects the general disillusionment that hassles the two post war generations and the deep spiritual isolation felt by men in a universe which he feels himself to be inconsequential and a stranger. Owing to socio-cultural and historical region, Indian literature in English of the recent decades also could not help being affected by it. V.S Naipaul, the first Nobel Prize winner of 21st century has become spokesman of emigrants. He delineates the Indian immigrants dilemma, his problems and plights in a fast changing world. In his works one can find the agony of an exile; the pangs of a man in search of meaning and identity: a daredevil who has tried to explore myths and see through fantasies. Out of his dilemma is born a rich body of writings which has enriched diasporic literature and the English language. The present paper will examine the feelings of rootlessness and alienation undergone by expatriates with reference to selected works of V.S Naipaul. Keywords Alienation, Rootlessness, Cultural Crisis, Expatriation. Introduction V. S. Naipaul, the mouthpiece of displacement and rootlessness is one of the most significant contemporary English Novelists.