The Little Bastard Worlds of V. S. Naipaul's the Mimic Men and a Flag on the Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LYNNE MACEDO Auteur and Author: a Comparison of the Works of Alfred Hitchcock and VS Naipaul

EnterText 1.3 LYNNE MACEDO Auteur and Author: A Comparison of the Works of Alfred Hitchcock and V. S. Naipaul At first glance, the subjects under scrutiny may appear to have little in common with each other. A great deal has been written separately about the works of both Alfred Hitchcock and V. S. Naipaul, but the objective of this article is to show how numerous parallels can be drawn between many of the recurrent ideas and issues that occur within their respective works. Whilst Naipaul refers to the cinema in many of his novels and short stories, his most sustained usage of the filmic medium is to be found in the 1971 work In a Free State. In this particular book, the films to which Naipaul makes repeated, explicit reference are primarily those of the film director Alfred Hitchcock. Furthermore, a detailed textual analysis shows that similarities exist between the thematic preoccupations that have informed the output of both men throughout much of their lengthy careers. As this article will demonstrate, the decision to contrast the works of these two men has, therefore, been far from arbitrary. Naipaul’s attraction to the world of cinema can be traced back to his childhood in Trinidad, an island where Hollywood films remained the predominant viewing fare throughout most of his formative years.1 The writer’s own comments in the “Trinidad” section of The Middle Passage bear this out: “Nearly all the films shown, apart from those in the first-run cinemas, are American and old. Favourites were shown again and Lynne Macedo: Alfred Hitchcock and V. -

"Other" in V. S. Naipaul's "A House for Mr. Biswas"

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 7 No. 1; February 2016 Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Flourishing Creativity & Literacy The Situation of Colonial 'Other' in V. S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr. Biswas Tahereh Siamardi (Corresponding author) Department of English Literature, Karaj Branch, Islamic Azad University, Karaj, Iran PO Box 31485-313, Karaj, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Reza Deedari Department of English Literature, Karaj Branch, Islamic Azad University, Karaj, Iran PO Box: 31485-313, Karaj, Iran Email: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.7n.1p.122 Received: 15/09/2015 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.7n.1p.122 Accepted: 11/11/2015 Abstract The focus of the present study is to demonstrate traces of Homi k. Bhabha’s notion of identity in V.S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr. Biswas (1961). As a prominent postcolonial figure, Bhabha has contemplated over the formation of identity in the colonizing circumstances. He discusses on what happens to the colonizer and the colonized while interacting each other, arguing that both the colonizer and the colonized influence one another during which their identity is formed, fragmented and alienated. In considering Naipaul’s A House for Mr. Biswas as postcolonial text, by the help of postcolonial theories of Homi Bhabha, it is argued that, mentioned novel sums up Naipaul’s approach to how individuals relate to places. This novel shows that individuals’ quest for home and a place of belonging is complicated first, by the reality of homelessness, and second, by the socio-cultural complexities peculiar to every place. -

Representation of Postcolonial Identity in Naipaul's Works

Vol. 4(10), pp. 451-455, December, 2013 DOI: 10.5897/IJEL2013.0481 International Journal of English and Literature ISSN 2141-2626 ©2013 Academic Journals http://www.academicjournals.org/IJEL Review Representation of postcolonial identity in Naipaul's works Bijender Singh V.P.O. Jagsi, Tehsil Gohana, District Sonepat, Haryana, India. Accepted 29 July, 2013 This paper attempts to explore representation of postcolonial identity in V. S. Naipaul’s three works A House for Mr. Biswas, A Bend in the River and An Enigma of Arrival. This paper attempts to relate how these three works are replete with the theme of identity as the chief protagonists of all these three novels hanker after to find a place for them in the world to assert their identities. Their minds vacillate between two contradictory cultures existing in that time. Researcher attempts to analyze the different strands of identity to make the work more comprehensive and to radicalize its global demand. The origin of the word ‘identity’ and its literary importance has been projected through this paper along with the different meanings of identity having a slight difference in their meaning. Postcolonial Diasporic authors and their works have been mentioned in the paper to carry out further research on the theme of postcolonial identity. V. S. Naipaul’s earned vacuity of female authors by challenging them and their rabble-rousing strengthened his identity in the world, has been assessed and analyzed. It has been studied how in these three novels, main protagonists try to claim their place in the world that is full of challenges in their real life and consequently, the environment of these novels poses a cultural-clash to make their journey of life more complicated and hard to live in antagonistic surroundings. -

Paradox of Freedom in the Novels of V. S. Naipaul

International Jour nal of Applie d Researc h 2020; 6(2): 100-102 ISSN Print: 2394-7500 ISSN Online: 2394-5869 Paradox of freedom in the novels of V. S. Naipaul Impact Factor: 5.2 IJAR 2020; 6(2): 100-102 www.allresearchjournal.com Received: 16-12-2019 Amandeep Accepted: 18-01-2020 Abstract Amandeep In addition to upsetting the cultural ties of the colonized people, colonization also led to their uprooting PGT English, AMSSS Ghaso and displacement. There was a massive transplantation of population between the colonies which Khurd, Jind, Haryana, India separated the colonized from their native lands and forced them to accommodate themselves in alien surroundings. This shift of population between the colonies was a deliberate measure taken to make the colonial societies heterogeneous, as homogeneous ones could have caused a political threat to the colonizers. this mixing up of various peoples created grave problems both at the individual and social levels. The intense alienation and sense of homelessness that such colonized individuals experience maybe ascribed to their displacement in the alien environment. Keywords: Paradox, freedom, novels Introduction Cultural colonization accomplished what military conquest alone could not have achieved for the colonizers. It paved its way into the minds of the colonised and made them complaisant victims. This colonization of the minds maimed the psyche of the colonized in a severe way. It robbed them of all originality and instead, instilled in them a dependency complex. The crippling effect of this complex manifests itself in the post independence period in the inability of the former colonized people to stand independently on their own and in their continuing dependence on the West for ideas and technology. -

V. S. Naipaul's a House for Mr Biswas: a Satire on Hinduism

V. S. NAIPAUL’S A HOUSE FOR MR BISWAS: A SATIRE ON HINDUISM Bijender Singh Research Scholar Dravidian University, Kuppam Andhra Pradesh, India Abstract Present paper is an attempt to explore how V.S. Naipaul’s novel A House for Mr Biswas is a satire on Hindu customs, traditions, rituals and rites. Naipaul’s novels are about his peregrination of orthodoxies prevalent in Hinduism. Through the paper the researcher tries to highlight that some Hindu Brahmins of high society claim themselves of supreme caste but their actions are inferior even to those people who are considered from the lowest stratum of society. They claim with proud to be Brahmins and follow the Hindu rituals blindly but they have no any quest for religion, salvation, sacrifice or goodness. They follow the Hindu rituals impassively because their ancestors did so. But they defy and infringe all rules and customs of the Hindu religion whenever the rituals come on their way. Hindus are famous for vegetarianism and their love for Hindu religious books. But in this novel they discard all rules to grind their own axes and follow the western culture blindly. These Hindus don’t refrain even from eating meat whereas even the egg is not touched in Hindu families. Such kind of themes have been projected and studied extensively in this paper. Key-Words: Hinduism, Traditions, Rituals, Post-Colony, Satire, Humanity. V. S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr. Biswas is a story of Indian Hindu migrants whose grand-parents have been migrated in Trinidad and Tobago as indentured labourers on the sugarcane estates and started living there permanently. -

Vol.5.Issue 2. 2017 (April-June)

Research Journal of English Language and Literature (RJELAL) A Peer Reviewed (Refereed) International Journal Vol.5.Issue 2. 2017 http://www.rjelal.com; (April-June) Email:[email protected] ISSN:2395-2636 (P); 2321-3108(O) RESEARCH ARTICLE HYBRIDITY AND MIMICRY IN V S NAIPAUL’S NOVELS A HOUSE FOR MR BISWAS, THE ENIGMA OF ARRIVAL & HALF A LIFE SUMAN WADHWA Ph D scholar Email:[email protected] ABSTRACT This paper is an attempt to probe into the cross cultural issues occurred due to Diaspora in the writings of V S Naipaul . It highlights the concept of hybridity , mimicry, nostalgia for a lost home, disillusionment of expatriation, fragmentation of the self, exuberance of immigration, assimilation, cultural translation and negotiation through the selected novels of the writer.It examines the feelings of rootlessness and alienation. The term hybridity has become very popular in postcolonial cultural criticism. Diasporas try their best at first to keep their own identity in their own community. But outside of community, their social identity is lost due to their migration from their homeland to adopted country. His novels deal with problematic intercultural relations and hyphenated identities the female characters in their novels count the benefits of gaining privacy, freedom, egalitarianism against the cost of losing the extended family spirituality tradition and status. Key Words: Rootlessness, Multiculturalism, Hybridity, Post colonialism, Displacement. ©KY PUBLICATIONS This paper maps out the Problems of the House For Mr Biswas(1961),The Enigma Of Arrival Indian expatriates and immigrants and brings in light (1987) & Half a life(2001) . their diasporic experience, feeling of rootlessness Postcolonial writers attempt to show and process of hybridization in the hostlands. -

Introduction

I INTRODUCTION The objective of the thesis has been to explore the rootlessness in the major fictional works of V.S. Naipaul, the-Trinidad-born English author. The emphasis has been on the analysis of his writings, in which he has depicted the images of home, family and association. Inevitably, in this research work on V.S. Naipaul’s fiction, multiculturalism, homelessness (home away from home) and cultural hybridity has been explored. Naipaul has lost his roots no doubt, but he writes for his homeland. He is an expatriate author. He gives vent to his struggle to cope with the loss of tradition and makes efforts to cling to the reassurance of a homeland. Thepresent work captures the nuances of the afore-said reality. A writer of Indian origin writing in English seems to have an object, that is his and her imagination has to be there for his/her mother country. At the core of diaspora literature, the idea of the nation-state is a living reality. The diaspora literature, however, focuses on cultural states that are defined by immigration counters and stamps on one’s passport. The diaspora community in world literature is quite complex. It has shown a great mobility and adaptability as it has often been involved in a double act of migration from India to West Indies and Africa to Europe or America on account of social and political resources. Writers like Salman Rushdie, RohingtonMistry, Bahrain Mukherjee, and V.S. Naipaul write from their own experience of hanging in limbo between two identities: non-Indian and Indian. -

IDENTITY and HOME in THREE CARIBBEAN AUTHORS By

IDENTITY AND HOME IN THREE CARIBBEAN AUTHORS By HARBHAJAN S. HIRA Bachelor of Science Guru Nanak Dev University Amritsar, Punjab (India) 1974 Master of Arts in English Hamburg University Hamburg, Germany 1987 Master of Arts in English California State University, Stanislaus Turlock, California 2001 Master of Arts in Education California State University, Dominguez Hills Carson, California 2007 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY July, 2020 IDENTITY AND HOME IN THREE CARIBBEAN AUTHORS Dissertation Approved: Dr. Timothy Murphy Dissertation Adviser Dr. Katherine Hallemeier Dr. Martin Wallen Dr. Alyson Greiner ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Several persons have helped making this project successful. My thanks go to Dr. Katherine Hallemeier, who provided feedback with an unprecedented speed in the final weeks of writing. Thanks are due to Professor Emeritus Martin Wallen as well. In spite of his retirement in 2019, Dr. Wallen kindly agreed to stay on the committee and help me get across the finish line. I also enormously benefited from his course on species, race, and surveillance, where I first discussed theorists such as Du Bois and Fanon. I want to thank Dr. Alyson Greiner of Geography too, who provided all the support that can be expected of an outside committee member. A big THANK YOU goes to Dr. Timothy Murphy, however. As my advisor and chair of the committee, he has been instrumental in securing the success of the project. He meticulously read and commented on every single chapter over the past year and a half. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} a Turn in the South by V.S. Naipaul a Turn in the South by V.S

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} A Turn In The South by V.S. Naipaul A Turn In The South by V.S. Naipaul. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Cloudflare Ray ID: 660afff8d86edfd7 • Your IP : 116.202.236.252 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. ISBN 13: 9780394564777. In the tradition of political and cultural revelation V.S. Naipaul so brilliantly made his own in Among The Believers, A Turn In The South, his first book about the United States, is a revealing, disturbing, elegiac book about the American South -- from Atlanta to Charleston, Tallahassee to Tuskegee, Nashville to Chapel Hill. From the Trade Paperback edition. "synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title. "Naipaul's chapters honor the diversity that marks the South. Conservatives and liberals, whites and blacks, men and women speak for themselves, and reveal the dark side of the story in their own ways. fascinating and revealing." -- Eugene D. Genovese, New Republic. "His writing is clean and beautiful, and he has a great eye for nuance. No American writer could achieve [his] kind of evenhandedness, and it gives Naipaul's perceptions an almost built-in originality." -- Atlantic Monthly. -

Locating VS Naipaul

V.S. Naipaul Homelessness and Exiled Identity Roshan Cader 12461997 Supervisors: Professor Dirk Klopper and Dr. Ashraf Jamal November 2008 Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (English) at the University of Stellenbosch Declaration I, Roshan Cader, hereby declare that the work contained in this research assignment/thesis is my own original work and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it at any university for a degree. Signature:……………………….. Date:…………………………….. 2 Abstract Thinking through notions of homelessness and exile, this study aims to explore how V.S. Naipaul engages with questions of the construction of self and the world after empire, as represented in four key texts: The Mimic Men, A Bend in the River, The Enigma of Arrival and A Way in the World. These texts not only map the mobility of the writer traversing vast geographical and cultural terrains as a testament to his nomadic existence, but also follow the writer’s experimentation with the novel genre. Drawing on postcolonial theory, modernist literary poetics, and aspects of critical and postmodern theory, this study illuminates the position of the migrant figure in a liminal space, a space that unsettles the authorising claims of Enlightenment thought and disrupts teleological narrative structures and coherent, homogenous constructions of the self. What emerges is the contiguity of the postcolonial, the modern and the modernist subject. This study engages with the concepts of “double consciousness” and “entanglements” to foreground the complex web and often conflicting temporalities, discourses and cultural assemblages affecting postcolonial subjectivities and unsettling narratives of origin and authenticity. -

The Development of V. S. Naipaul As a Writer

v. NAIPAUI, AS J3Y ANGELA AHYLIA SEUKERAN, B.A. (Hons.) A Thesis ;3uomittc0. to the 3chool of Grac1ttate Studies in Partial FLl.lfilment of the Requirements for the Degree I':1d.Iaster Uni v8r;:;i ty September 19'15. MASTER OF ARTS (1975) (EnGlish) Hamilton, Ontario TITLl!~: The Development of V. :3. l'Iaipaul as a ~·Jriter. Am:HOR: An.gela Ahylia Seukeran, D. A. (Wcl:laster) SUP2RVI30R: Dr. J. Dale. NUI;;DER OF PAGES ~ VI; 92, ii -----.---AB3TRAc r This thesis explores the themes prevalent in the novels of V. S. Naipaul and examines hi.s development from a regional v/ri ter to one with a more universal appeal. In Chapter One an attempt is made to establish a critical b<;lckground by briefly di.scussinc the ideas revealed in his non-fictional works. Chapter One also discusses the themes of the early ?tree-t.. Chapter TvlO of this thesis deals with the themes of ~r:,. }Io'J.se for Er, Bisvras and I.1r. Stone and the Kni:xhh, Corn-Danion. _... __ ...-__ ._----_._-_. ------_._---------..... _--------- These nov-els are seen as representing a turning point in Naipaul's developr:lent as a \-,11:i te:c. Chapter Three focuses on 1h~._ f,~ir~.:i.9 1\1en and "A Flag on the Island", and sees the se two works as representing a bleaker but Dore philosophical mood by the author. .In Ii ~ Staj:;e is examined in the final Chapte:c of this thesis and Naipaul i s effectiveness is evaluated. -

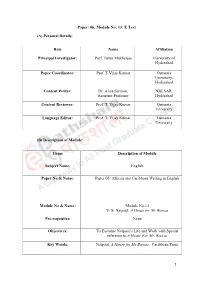

Paper: 06; Module No: 13: E Text

Paper: 06; Module No: 13: E Text (A) Personal Details: Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee University of Hyderabad Paper Coordinator: Prof. T Vijay Kumar Osmania University, Hyderabad Content Writer: Dr. Alice Samson, NALSAR, Assistant Professor Hyderabad Content Reviewer: Prof. T. Vijay Kumar Osmania University Language Editor: Prof. T. Vijay Kumar Osmania University (B) Description of Module: Items Description of Module Subject Name: English Paper No & Name: Paper 06: African and Caribbean Writing in English Module No & Name: Module No.13 V. S. Naipaul: A House for Mr Biswas V. S. Naipaul: A House for Mr Biswas Pre-requisites: None Objectives: To Examine Naipaul’s Life and Work with Special reference to A House For Mr. Biswas Key Words: Naipaul, A House for Mr Biswas, Caribbean Prose 1 Summary: The lesson, through a reading of the novel A House for Mr. Biswas, introduces the reader to the life and works of Sir V.S. Naipaul. It contextualises the novel, discusses the plot, the main characters and the main themes that are addressed in the novel. Module-I: Introduction to A House for Mr. Biswas Listed amongst the 100 best novels written in English language in the twentieth century, V.S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr. Biswas is one of the most significant novels to have been written by a Caribbean author. The novel describes the travails of the protagonist Mohun Biswas, who seeks to own a house in Trinidad. The novel is set in the first half of the twentieth century. Even as the novel depicts the desires and insecurities of Mohun, it rather humorously depicts the lives of the various members of the gregarious Tulsi household.