Welten Der Philosophie A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HUMAN DIGNITY Discourses on Universality and Inalienability

HUMAN DIGNITY Discourses on Universality and Inalienability One World Theology (Volume 8) HUMAN DIGNITY Discourses on Universality and Inalienability 8 Edited by Klaus Krämer and Klaus Vellguth CLARETIAN COMMUNICATIONS FOUNDATION, INC. HUMAN DIGNITY Discourses on Universality and Inalienability Contents (One World Theology, Volume 8) Copyright © 2017 by Verlag Herder GmbH, Freiburg im Breisgau Published by Claretian Communications Foundation, Inc. U.P. P.O. Box 4, Diliman 1101 Quezon City, Philippines Preface ......................................................................................... ix Tel.: (02) 921-3984 • Fax: (02) 921-6205 [email protected] www.claretianpublications.ph Anthropological Remarks on Human Dignity Claretian Communications Foundation, Inc. (CCFI) is a pastoral endeavor of the Human Dignity in the Light of Anthropology ....................... 3 Claretian Missionaries in the Philippines that brings the Word of God to people from all and the History of Ideas walks of life. It aims to promote integral evangelization and renewed spirituality that is geared towards empowerment and total liberation in response to the needs and challenges Josef Schuster of the Church today. Reaffirming the Theology of Human Dignity in Africa .......... 17 CCFI is a member of Claret Publishing Group, a consortium of the publishing houses of the Claretian Missionaries all over the world: Bangalore, Barcelona, Buenos Aires, Chennai, Critical challenges and salient hopes in Tanzania Colombo, Dar es Salaam, Lagos, Macau, Madrid, Manila, Owerry, São Paolo, Varsaw and Aidan G. Msafiri Yaoundè. Anthropological Annotations on Human Dignity from an Asian Perspective ............................................................... 27 Francis-Vincent Anthony Discussion Forum as the Survival Strategy ........................ 37 of a Kaqchikel Community in Guatemala Andreas Koechert Roots of Human Dignity in the Specific Context An Historical Perspective on Violations of Dignity ............. -

Als Die Kirche Weltkirche Wurde

Rahner Lecture 2018 Rahner Lecture 2018 Johannes Herzgsell SJ Karl Rahners Theologie der Freiheit Johannes Herzgsell SJ Karl Rahners Theologie der Freiheit Rahner Lecture 2018 Veröffentlichung des Karl Rahner-Archivs München In Verbindung mit der Hochschule für Philosophie, München im Verlag der Universitätsbibliothek Freiburg i.Br. Herausgegeben von Harald Schöndorf SJ und Albert Raffelt Karl Rahners Theologie der Freiheit von Johannes Herzgsell SJ München – Freiburg i.Br. 2018 Elektronisches Original unter: <DOI 10.6094/978-3-928969-73-4> © Freiburg im Breisgau : Universitätsbibliothek 2018 © Umschlagsfoto: Verlag Herder, Freiburg i.Br. © Foto S 8: Nachlaß Kardinal Lehmann; S. 54: Dr. Barbara Nichtweiß, Mainz 2018; sonstige Fotos: A. Raffelt; für die abgebildeten Buchumschläge: die Verlage. ISSN 1868-839X ISBN 978-3-928969-73-4 Inhalt Die Herausgeber Vorwort .................................................................................................................... 7 Harald Schöndorf SJ Einführung ............................................................................................................... 9 Reinhard Kardinal Marx Grußwort ............................................................................................................... 12 Martin Stark SJ Grußwort des Provinzials der Deutschen Provinz der Jesuiten ............................. 16 Philip Endean SJ Grußwort ............................................................................................................... 18 Johannes Wallacher Grußwort -

Elochukwu Uzukwu Cssp. Professor, Department of Theology, Duquesne University Former Holder

Elochukwu Uzukwu C.S.Sp. Professor, Department of Theology, Duquesne University Former Holder (2011-2016), Father Pierre Schouver C.S.Sp. Endowed Chair in Mission 600 Forbes Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15282 Tel. 412.396.2077 E-mail: [email protected] 1. Education: 1976-79: University of St Michael’s College, Toronto School of Theology, University of Toronto (ThD - 1979). 1975-76: University of St Michael’s College, University of Toronto, Toronto School of Theology (MTh - 1976) 1969-72: Bigard Memorial Seminary Enugu, Nigeria – Affiliated to Urban University Rome (S.T.B. of Urban University Rome – 1972); 2. Scholarships and Fellowships: 2000-2001: Missio Aachen, Institute of Missiology – Grant to research topic on "African Christian Theology" (Research completed: God, Spirit and Human Wholeness) 2008: Fall Semester – Dept. of Mission Theology and Cultures, Milltown Institute – Grant to Research “Church Family of God”. 3. Previous Positions: 3.1. Academic- Full Time Teaching: 2009- Department of Theology, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, PA 15282 (Sacraments; Doctrine – God, Ecclesiology; African and African American Christologies; Global and Cultural Perspectives; Theological View of the Person; Foundations in Theology; African Religions) 2001-2009 Kimmage Mission Institute & Milltown Institute, Dublin, Ireland (Liturgy; Mission Theology; Contextual issues in theology – e.g. African and African American Christologies in dialogue with world Christianity; Church Family-of-God;) 1987-2001 Spiritan International School of Theology Enugu, Nigeria (Liturgy, Sacraments, Missiology; Contextual Theology); 1982-88: Bigard Memorial Seminary, Enugu, Nigeria (Liturgy, Sacraments, Missiology, Pastoral; Contextual Theology); 1979-82: Grand Séminaire Régional Brazzaville, Congo (Liturgy, Sacraments, Missiology, Pastoral) ; 1968-1969: Holy Ghost Juniorate Ihiala – Religious Studies and History. -

Ludwig Van Beethoven: the Heard and the Unhearing

Bernhard Richter / Wolfgang Holzgreve / Claudia Spahn (ed.) Ludwig van Beethoven: the Heard and the Unhearing A Medical-Musical-Historical Journey through Time Bernhard Richter / Wolfgang Holzgreve / Claudia Spahn (ed.) Ludwig van Beethoven: the Heard and the Unhearing Bernhard Richter / Wolfgang Holzgreve / Claudia Spahn (ed.) Ludwig van Beethoven: the Heard and the Unhearing A Medical-Musical-Historical Journey through Time Translated by Andrew Horsfield ® MIX Papier aus verantwor- tungsvollen Quellen ® www.fsc.org FSC C083411 © Verlag Herder GmbH, Freiburg im Breisgau 2020 All rights reserved www.herder.de Cover design by University Hospital Bonn Interior design by SatzWeise, Bad Wünnenberg Printed and bound by CPI books GmbH, Leck Printed in Germany ISBN 978-3-451-38871-2 Words of welcome from Nike Wagner Bonn is not only the birthplace of Beethoven. The composer spent the first two decades of his life here, became a professional musician in this city and absorbed here the impulses and ideas of the Enlightenment that shaped his later creative output, too. To this extent, it is logical that Bonn is preparing to celebrate Beethoven with a kind of “Cultural Capital Year” to mark his 250th birthday. In this special year, opportunities have been cre- ated in abundance to engage with the “great mogul,” as Haydn called him. There is still more to be discovered in his music, as in his life, too. In this sense, a symposium that approaches the phenomenon of Beethoven from the music-medicine perspective represents an additional and necessary enrichment of the anni- versary year. When I began my tenure as artistic director of the Beethoven- feste Bonn in 2014, I set out to bring forth something that was always new, special and interdisciplinary. -

Ecumenical Approaches in Light of the Document from Conflict to Communion

ultimately fruitful in the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Jus- tification, ratified by the Lutheran World Federation and the Roman Catholic Church on October 31, 1999. The article then explains how the document From Conflict to Communion, achieved through the same historical-critical- hermeneutic method, has addressed four topics Reform and Reformation: that traditionally have been in dispute: first, the relationship of grace/ Ecumenical Approaches in Light of the freedom and faith/works in justification and sanctification; second, the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist and the sacrifice of the Mass; 1 Document From Conflict to Communion third, the divine origin of the ordained ministry and its relationship Wolfgang Thönissen to the common priesthood of all the faithful; and fourth, the relation- Johann- Adam- Möhler Institute for Ecumenism ship among scripture, tradition, and the magisterium. Beginning from these insights, the document shows how the different doctrinal empha- ses of Lutherans and Catholics, freed from polemical emphases, should not be mutually exclusive and therefore should not preclude consensus This article begins by recalling the path that Catholic and Lutheran on fundamental truths. Giving birth to a different church was not theological and historical research has taken over the last century to lib- Luther’s original intent. Hence it can be argued that in these days erate the image of Martin Luther from one-sided interpretations and the condemnations against Martin Luther ought to be re-examined, distortions. The dialogue between the two churches demonstrates how making the figure of Luther available to being discovered beyond the much Luther and his theology are rooted in the great tradition of the regrettable historical events. -

Envisioning Futures for the Catholic Church Hellemans, Staf; Jonkers, Peter

Tilburg University Envisioning Futures for the Catholic Church Hellemans, Staf; Jonkers, Peter Publication date: 2018 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Hellemans, S., & Jonkers, P. (2018). Envisioning Futures for the Catholic Church. Council for Research in Values and Philosophy. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. sep. 2021 Cultural Heritage and Contemporary Change Series VIII, Christian Philosophical Studies 23 Envisioning Futures for the Catholic Church Edited by Staf Hellemans & Peter Jonkers The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Copyright © 2018 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Gibbons Hall B-20 620 Michigan Avenue, NE Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Names: Hellemans, Staf, editor. -

Bibliographie Zur Deutschsprachigen

li B I B L I O G R A F I E D E U T S C H S P R A C H I G E L I T E R A T U R M A R I O L O G I E U N D M A R I E N V E R E H R U N G Stand: 8. Juni 2021, 160 S., ca. 3.200 Titel Obiges Bild zeigt einen Kupferstich von 1648, das Frontinspiz der ersten großen Bibliografie zur Marienliteratur, verfasst vom italienischen Theologen Ippolito Marracci (1612-1675) in Rom. Vergleichbares hat es danach lange nicht gegeben. Seit 1950 werden mariologische Beiträge von der Theologischen Fakultät „Marianum“ in Rom in regelmäßigen Abständen akribisch zusammengestellt und als „Bibliografia mariana“ in jeweils mehrere Jahre umfassende Bänden veröffentlicht, anfangs unter Leitung von Giuseppe M. Besutti OSM (+ 1994), Ermanno M. Toniolo (bis 1998), heute von Servano M. Danieli. Es erschienen bis 2019 sechzehn Bände über internationale mariologische Arbeiten auch deutscher Provenienz (seit 1948, Buchtitel und Zeitschriftenartikel). Diese Bibliografie kann unter http://www.culturamariana.com/BibliografiaMariana/BibliografiaMar.htm im Internet bandweise heruntergeladen werden. Mariologisch-marianische Veröffentlichungen aus Deutschland bis 1647 bietet das erwähnte Werk Marraccis; „Bibliotheca mariana alphabetico ordine digesta“ (Edizioni AMI, Roma 2005, 992 S.). Sie listet die marianischen Werke des Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit auf, darunter die Werke von 296 Autoren deutscher Herkunft, zumeist in lateinischer Sprache verfasst. 1987 legte Martina Instinsky- Anrich eine 178 Seiten starke Broschüre „Deutschsprachige Marianische Literatur 1945-1987“ vor (hg. vom IMAK, Kevelaer, nur Buchtitel). Die hier gebotene Bibliografie versteht sich als Ergänzung, da sie versucht, die deutschsprachigen Titel seit dem 17. -

Walther Köhler Collection

Walther Köhler Collection Finding List Pub. Author Title Year 150 Jahre, Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 1780-1930; 1 1930 Jubiläumsschrift 17. kapitel des ägyptischen Totenbuches und seine 2 1912 religionsgeschichtliche bedeutung Aarauer Studentenkonferenz, 1920 (XXIV Christl. 3 1920 Studentenkonferenz in Aarau) 15.-17. April 1920 Abwehr der königstreuen patriotisch gesinnten 4 Neuapostolischen Gemeinde gegen feindliche 1900? Angriffe Achelis, E. Christian 5 (Ernst Christian), 1838- Praktische Theologie 1893 1912 6 Achelis, Hans, 1865-1937 Marmorkalendar in Neapel 1929 Über die Syphilisschriften Theophrasts von Hohenheim. 1. Die Pathologie der Syphilis. Mit 7 Achelis, Johann Daniel 1939 einem Anhang: Zur Frage der Echtheit des dritten Buches der Grossen Wundarznei 8 Aconcio, Iacopo, d. 1566 Satan's stratagems 1940 9 Aconcio, Iacopo, d. 1566 Jacobus Acontius' tractaat De methodo 1932 Jacobi Acontii Satanae stratagematum libri octo; Ad Johannem Wolphium eiusque ad Acontium 10 Aconcio, Iacopo, d. 1566 epistulae; Epistula apologetica pro Adriano de 1927 Haemstede; Epistula ad ignotum quendam de natura Christi. Editio critica Acontiana: Abhandlungen und Briefe des Jacobus 11 Aconcio, Iacopo, d. 1566 1932 Acontius [OVERSIZE] 12 Adam, August, 1878- Arbeit und Besitz nach Ratherius von Verona 1927 13 Adam, Karl, 1876-1966 Christus und der Geist des Abendlandes 1928 Vom Krakauer Vertrag bis zum Tode Albrechts, 14 Adam, Vertulani 1927? des ersten Herzogs von Preussen (1525-1568) Adolf Stoecker, Kämpfer und Christ, Zu seinem 15 1935 100. Geburtstag am 11. Dezember 1935 Adolph, Heinrich August 16 Theologie, Kirche, Universität 1933 Karl, 1885- Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft im Spiegel 17 Aeberhard, Rene, 1916- auslaendischer Schriften , von 1474 bis zur Mitte 1941 des 17. Jahrdunderts Religionsdelikte in ihrer geschichtlichen Entwicklung, ihre Behandlung im geltenden Recht 18 Aebli, Fritz 1914 mit Berücksichtigung der deutschen und schweizerischen Strafgesetzentwürfe .. -

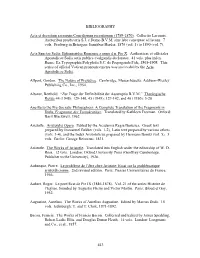

BIBLIOGRAPHY Acta Et Decretum Sacrorum

BIBLIOGRAPHY Acta et decretum sacrorum Conciliorum recentiorum (1789-1870). Collectio Lacensis. Auctoribus presbyteris S.J. e Domo B.V.M. sine labe conceptae ad lacum. 7 vols. Freiburg in Briesgau: Sumtibus Herder, 1870 (vol. 1) to 1890 (vol. 7). Acta Sanctae Sedis: Ephemerides Romanae a ssmo d.n. Pio X. Authenticae et officiales Apostolicae Sedis actis publice evulgandis declaratae. 41 vols. plus index. Rome: Ex Typographia Polyglotta S.C. de Propaganda Fide, 1865-1908. This series of official Vatican pronouncements was succeeded by the Acta Apostolicae Sedis. Allport, Gordon. The Nature of Prejudice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc., 1954. Altaner, Berthold. “Zur Frage der Definibilität der Assumptio B.V.M.” Theologische Revue 44 (1948): 129-140, 45 (1949): 129-142, and 46 (1950): 5-20. Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers: A Complete Translation of the Fragments in Diels, Fragmente der Vorsokratiker. Translated by Kathleen Freeman. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1962. Aristotle. Aristotelis Opera. Edited by the Academia Regia Borusica. Greek text prepared by Immanuel Bekker (vols. 1-2), Latin text prepared by various others (vols. 3-4), and the Index Aristotelicus prepared by Hermann Bonitz (vol. 5). 5 vols. Berlin: George Reimerus, 1831. Aristotle. The Works of Aristotle. Translated into English under the editorship of W. D. Ross. 12 vols. London: Oxford University Press (Geoffrey Cumberlege, Publisher to the University), 1928. Aubenque, Pierre. Le problème de l’être chez Aristote: Essai sur la problématique aristotélicienne. 2nd revised edition. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1966. Aubert, Roger. Le pontificat de Pie IX (1846-1878). Vol. 21 of the series Histoire de l’Eglise, founded by Augustin Fliche and Victor Martin. -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie 2021 a 24

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe A Monografien und Periodika des Verlagsbuchhandels Wöchentliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2021 A 24 Stand: 16. Juni 2021 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main) 2021 ISSN 1869-3946 urn:nbn:de:101-20201120239 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. In Reihe A werden Medienwerke, die im Verlagsbuch- chende Menüfunktion möglich. Die Bände eines mehrbän- handel erscheinen, angezeigt. Auch außerhalb des Ver- digen Werkes werden, sofern sie eine eigene Sachgrup- lagsbuchhandels erschienene Medienwerke werden an- pe haben, innerhalb der eigenen Sachgruppe aufgeführt, gezeigt, wenn sie von gewerbsmäßigen Verlagen vertrie- ansonsten -

Kurnyek Dissertation

The Concept of Liturgical Reform in the Writings of Romano Guardini and Joseph Ratzinger / Pope Benedict XVI: A Comparative Analysis Róbert Kürnyek Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Theology, Saint Paul University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate of Philosophy degree in Theology Ottawa, Canada 2016 © Róbert Kürnyek, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS _________________________________________________________ 1 SIGLA AND ABBREVIATIONS ___________________________________________________ 3 INTRODUCTION _______________________________________________________________ 4 1. LITURGY AND THEOLOGY: CONNECTION AND DEVELOPMENT ______________ 10 1.1 SHIFT IN THE INTERPRETATION OF PROSPER ’S ADAGE _______________________________ 12 1.1.1 The Original Meaning of Prosper of Aquitaine’s Adage _________________________ 15 1.1.2 Lex Orandi – Lex Credendi in Pope Pius XII’s Encyclical Mediator Dei ____________ 18 1.1.2.1 The Teaching of the Encyclical _______________________________________________ 18 1.1.2.2 Liturgical and Theological Consequences _______________________________________ 21 1.1.3 The Understanding of Prosper’s Adage in the Liturgical Movement _______________ 25 1.1.4 Liturgy and Theology in the Time of the Liturgical Reform of Vatican II ____________ 29 1.2 THEOLOGY AND LITURGY BY ROMANO GUARDINI _________________________________ 33 1.2.1 An Important Category: Der Gegensatz _____________________________________ 33 1.2.2 References to Liturgy and Theology ________________________________________ -

Beyond Secularization and Post-Secularity—Joseph Ratzinger’S and Józef Tischner’S Concept of a Breakthrough

religions Article Beyond Secularization and Post-Secularity—Joseph Ratzinger’s and Józef Tischner’s Concept of a Breakthrough Jarosław Jagiełło The Faculty of Philosophy, The Ponitifical University of John Paul II in Krakow, 31-002 Kraków, Poland; [email protected] Abstract: The inspiration to write this article was provided by the assessment made by Joseph Ratzinger/Benedict XVI: man of the Western civilization is undergoing a deep spiritual crisis. There- fore, conversion, a breakthrough, or spiritual renewal is absolutely necessary. Without this renewal, humanity will become a victim of its own thinking, wanting and acting. As I search for a philosophical description of the breakthrough postulated by Benedict XVI, I refer to the original philosophical and religious thought of Polish philosopher Józef Tischner, who presents the question of the breakthrough at the anthropological-axiological level, where he exposes the issue of interpersonal correlation. The basis for the permanent existence of this correlation is man’s ethical awareness grounded in the ethic of dialogue. This grounding is particularly important, because it is a guarantee for overcoming internal and external threats to the existence of a religious community. Tischner presents the issue of this grounding against the background of the secularization of Western society. By distinguishing relative secularization from radical secularization, Tischner provides an insightful analysis of the phenomenon of the apparent and the true sacrum. For a real breakthrough, only the true sacrum, which Tischner believes to appear at the level of the Christian sanctum, is of primary importance. He understands sanctum as holiness grounded in goodness. It is holiness that is the real key to Citation: Jagiełło, Jarosław.