Taiwan's Marginalized Role in International Security: Paying a Price

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taiwan: Major U.S. Arms Sales Since 1990

Order Code RL30957 CRS Report for Congress .Received through the CRS Web Taiwan: Major U.S. Arms Sales Since 1990 Updated July 5, 2005 Shirley A. Kan Specialist in National Security Policy Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Taiwan: Major U.S. Arms Sales Since 1990 Summary This report, updated as warranted, discusses U.S. security assistance to Taiwan, or Republic of China (ROC), including policy issues for Congress and legislation. The Taiwan Relations Act (TRA), P.L. 96-8, has governed U.S. arms sales to Taiwan since 1979, when the United States recognized the People’s Republic of China (PRC) instead of the ROC. Two other relevant parts of the “one China” policy are the August 17, 1982 U.S.-PRC Joint Communique and the “Six Assurances” made to Taiwan. (Also see CRS Report RL30341, China/Taiwan: Evolution of the “One China” Policy — Key Statements from Washington, Beijing, and Taipei, by Shirley Kan.) Despite the absence of diplomatic relations or a defense treaty, U.S. arms sales to Taiwan have been significant. In addition, the United States has expanded military ties with Taiwan after the PRC’s missile firings in 1995-1996. At the U.S.-Taiwan arms sales talks on April 24, 2001, President George W. Bush approved for possible sale: diesel-electric submarines, P-3 anti-submarine warfare (ASW) aircraft (linked to the submarine sale), four decommissioned U.S. Kidd-class destroyers, and other items. Bush also deferred decisions on Aegis- equipped destroyers and other items, while denying other requests. -

EUSA Year Magazine 2019-2020

EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY SPORTS ASSOCIATION YEAR 2019/20MAGAZINE eusa.eu CONTENTS Page 01. EUSA STRUCTURE 4 02. EUROPEAN UNIVERSITIES CHAMPIONSHIPS 2019 9 03. ENDORSED EVENTS 57 04. CONFERENCES AND MEETINGS 61 05. PROJECTS 75 06. EU INITIATIVES 85 07. UNIVERSITY SPORT IN EUROPE AND BEYOND 107 08. PARTNERS AND NETWORK 125 09. FUTURE PROGRAMME 133 Publisher: European University Sports Association; Realisation: Andrej Pišl, Fabio De Dominicis; Design, Layout, PrePress: Kraft&Werk; Printing: Dravski tisk; This publication is Photo: EUSA, FISU archives free of charge and is supported by ISSN: 1855-4563 2 WELCOME ADDRESS Dear Friends, With great pleasure I welcome you to the pages of Statutes and Electoral Procedure which assures our yearly magazine to share the best memories minimum gender representation and the presence of the past year and present our upcoming of a student as a voting member of the Executive activities. Committee, we became – and I have no fear to say – a sports association which can serve as an Many important events happened in 2019, the example for many. It was not easy to find a proper year of EUSA’s 20th anniversary. Allow me to draw tool to do that, bearing in mind that the cultural your attention to just a few personal highlights backgrounds of our members and national here, while you can find a more detailed overview standards are so different, but we nevertheless on the following pages. achieved this through a unanimous decision- making process. In the build up to the fifth edition of the European Adam Roczek, Universities Games taking place in Belgrade, I am proud to see EUSA and its Institute continue EUSA President Serbia, the efforts made by the Organising their active engagement and involvement in Committee have been incredible. -

Taiwan's Nationwide Cancer Registry System of 40 Years: Past, Present

Journal of the Formosan Medical Association (2019) 118, 856e858 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect journal homepage: www.jfma-online.com Perspective Taiwan’s Nationwide Cancer Registry System of 40 years: Past, present, and future Chun-Ju Chiang a,b, Ying-Wei Wang c, Wen-Chung Lee a,b,* a Institute of Epidemiology and Preventive Medicine, College of Public Health, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan b Taiwan Cancer Registry, Taipei, Taiwan c Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taipei, Taiwan Received 29 October 2018; accepted 15 January 2019 The Taiwan Cancer Registry (TCR) is a nationwide demonstrate that the TCR is one of the highest-quality population-based cancer registry system that was estab- cancer registries in the world.3 lished by the Ministry of Health and Welfare in 1979. The The TCR publishes annual cancer statistics for all cancer data of patients with newly diagnosed malignant cancer in sites, and the TCR’s accurate data is used for policy making hospitals with 50 or more beds in Taiwan are collected and and academic research. For example, the Health Promotion reported to the TCR. To evaluate cancer care patterns and Administration (HPA) in Taiwan has implemented national treatment outcomes in Taiwan, the TCR established a long- screening programs for cancers of the cervix uteri, oral form database in which cancer staging and detailed treat- cavity, colon, rectum, and female breast,4 and the TCR ment and recurrence information has been recorded since database has been employed to verify the effectiveness of 2002. Furthermore, in 2011, the long-form database these nationwide cancer screening programs for reducing began to include detailed information regarding cancer cancer burdens in Taiwan.5,6 Additionally, liver cancer was site-specific factors, such as laboratory values, tumor once a major health problem in Taiwan; however, since the markers, and other clinical data related to patient care. -

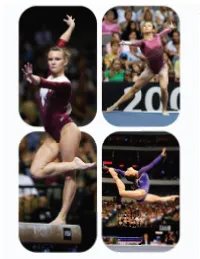

Horton Wins All-Around Title at Õ 09 Visa

WOMEN SLOAN WINS WOMEN’S ALL-AROUND TITLE At ’09 VISA CHAMPIONSHIPS Photos by John Cheng ridget Sloan, a 2008 Olympic team silver medalist from Sharp’s Gymnastics, won her first U.S. all-around title at the 2009 Visa Championships at the American Airlines Center in Dallas. Sloan, who was third after the first day of competition, came from behind to win the title with a score 117.550. “It feels great to win the Visa Championships,” said Sloan. “The first day didn’t go as planned, but today went well.” Sloan’s top scores of the two-day competition were for her Yurchenko double full vault (15.000), and her floor routine which includes a one-and-a-half to triple twist for her first pass (15.050). 2008 Olympic Team alternate Ivana Hong of WOGA finished a Kytra Hunter Mackenzie Caquatto close second in the all-around at 117.250. Hong’s top scores were on vault for her Yurchenko double (15.250) and her beam routine that included a flip flop series into a double pike dismount (15.200). WOGA’s Rebecca Bross, who led the competition after day one, landed in third place with an all-around score of 116.600. Bross had !" #$% a rough bar routine on day two that pulled her down in the rankings. Her top score of the competition was a 15.300 for her double twisting Yurchenko vault and a 15.050 for her jam-packed bar routine on the first day of competition. Kytra Hunter of Hill’s Gymnastics finished fourth in the all-around with 113.750 and took third on floor, showing a huge piked double Arabian and double layout. -

MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS and HOSTS Published April 2013 © 2013 Sportbusiness Group All Rights Reserved

THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS Published April 2013 © 2013 SportBusiness Group All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher. The information contained in this publication is believed to be correct at the time of going to press. While care has been taken to ensure that the information is accurate, the publishers can accept no responsibility for any errors or omissions or for changes to the details given. Readers are cautioned that forward-looking statements including forecasts are not guarantees of future performance or results and involve risks and uncertainties that cannot be predicted or quantified and, consequently, the actual performance of companies mentioned in this report and the industry as a whole may differ materially from those expressed or implied by such forward-looking statements. Author: David Walmsley Publisher: Philip Savage Cover design: Character Design Images: Getty Images Typesetting: Character Design Production: Craig Young Published by SportBusiness Group SportBusiness Group is a trading name of SBG Companies Ltd a wholly- owned subsidiary of Electric Word plc Registered office: 33-41 Dallington Street, London EC1V 0BB Tel. +44 (0)207 954 3515 Fax. +44 (0)207 954 3511 Registered number: 3934419 THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS Author: David Walmsley THE BID BOOK MATCHING SPORTS EVENTS AND HOSTS -

Democratic Values and Democratic Support in East Asia

Democratic Values and Democratic Support in East Asia Kuan-chen Lee [email protected] Postdoctoral fellow, Institute of Political Science, Academia Sinica Judy Chia-yin Wei [email protected] Postdoctoral fellow, Center for East Asia Democratic Studies, National Taiwan University Stan Hok-Wui Wong [email protected] Assistant Professor, Department of Applied Social Sciences, Hong Kong Polytechnic University Karl Ho [email protected] Associate Professor, School of Economic, Political, and Policy Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas Harold D. Clarke [email protected] Ashbel Smith Professor, School of Economic, Political, and Policy Sciences, University of Texas at Dallas Introduction In East Asia, 2014 was an epochal year for transformation of social, economic and political orders. Students in Taiwan and Hong Kong each led a large scale social movement in 2014 that not only caught international attention, but also profoundly influenced domestic politics afterwards. According to literature of political socialization, it is widely assumed that the occurrences of such a huge event will produce period effects which bring socio-political attitudinal changes for all citizens, or at least, cohort effects, which affect political views for a group of people who has experienced the event in its formative years. While existing studies have accumulated fruitful knowledge in the socio-political structure of the student-led movement, the profiles of the supporters in each movement, as well as the causes and consequences of the student demonstrations in the elections (Ho, 2015; Hawang, 2016; Hsiao and Wan, 2017; Stan, forthcoming; Ho et al., forthcoming), relatively few studies pay attention to the link between democratic legitimacy and student activism. -

The History and Politics of Taiwan's February 28

The History and Politics of Taiwan’s February 28 Incident, 1947- 2008 by Yen-Kuang Kuo BA, National Taiwan Univeristy, Taiwan, 1991 BA, University of Victoria, 2007 MA, University of Victoria, 2009 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of History © Yen-Kuang Kuo, 2020 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee The History and Politics of Taiwan’s February 28 Incident, 1947- 2008 by Yen-Kuang Kuo BA, National Taiwan Univeristy, Taiwan, 1991 BA, University of Victoria, 2007 MA, University of Victoria, 2009 Supervisory Committee Dr. Zhongping Chen, Supervisor Department of History Dr. Gregory Blue, Departmental Member Department of History Dr. John Price, Departmental Member Department of History Dr. Andrew Marton, Outside Member Department of Pacific and Asian Studies iii Abstract Taiwan’s February 28 Incident happened in 1947 as a set of popular protests against the postwar policies of the Nationalist Party, and it then sparked militant actions and political struggles of Taiwanese but ended with military suppression and political persecution by the Nanjing government. The Nationalist Party first defined the Incident as a rebellion by pro-Japanese forces and communist saboteurs. As the enemy of the Nationalist Party in China’s Civil War (1946-1949), the Chinese Communist Party initially interpreted the Incident as a Taiwanese fight for political autonomy in the party’s wartime propaganda, and then reinterpreted the event as an anti-Nationalist uprising under its own leadership. -

2013 National Defense Report

National Defense Report Ministry of National Defense, ROC 2013 1 Minister’s Foreword 17 Introduction 21 Part 1 Strategic Environment 25 Part 2 General Plan of National Defense 73 Chapter 1 Security Situation 26 Chapter 3 National Defense Strategy 74 Section 1 Global Security Environment 27 Section 1 National Defense Policy 75 Section 2 Asia-Pacific Security Situation 34 Section 2 National Defense Strategies 78 Section 3 Military Strategy 85 Chapter 2 Security Challenges 44 Section 1 Current Status and Chapter 4 National Defense Administration 92 Developments of the PLA 45 Section 1 Military Strength Reformation 93 Section 2 Military Capabilities and 94 Threat of the PRC 57 Section 2 Military Service Reformation 98 Section 3 Security Challenges Section 3 Talent Cultivation of the ROC 67 Section 4 Armaments Mechanism 100 Section 5 Military Exchanges 106 Section 6 National Defense Legal System 108 Section 7 Morale and Ethical Education 113 Section 8 Crisis Response 116 Section 9 Care for Servicemen 119 Section 10 Gender Equality 121 2 Part 3 National Defense Capabilities 123 Part 4 All-out National Defense 197 Chapter 5 National Defense Force 124 Chapter 7 All-out Defense 198 Section 1 National Defense Organization 125 Section 1 National Defense Education 199 Section 2 Joint Operations Effectiveness 136 Section 2 Defense Mobilization 204 Section 3 Information and Electronic Warfare Capabilities 141 Chapter 8 Citizen Services 210 Section 4 Logistics Support 144 Section 1 Disaster Prevention and Relief 211 Section 5 Reserve Capability Buildup -

An Introduction to Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) and Search and Rescue (SAR) Organizations in Taiwan

CENTER FOR EXCELLENCE IN DISASTER MANAGEMENT & HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE An Introduction to Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) and Search and Rescue (SAR) Organizations in Taiwan WWW.CFE-DMHA.ORG Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................2 Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) Organizations ..................................3 Search and Rescue (SAR) Organizations ..........................................................................18 Appendix A: Taiwan Foreign Disaster Relief Assistance ....................................................29 Appendix B: DOD/USINDOPACOM Disaster Relief in Taiwan ...........................................31 Appendix C: Taiwan Central Government Disaster Management Structure .......................34 An Introduction to Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) and Search and Rescue (SAR) Organizations in Taiwan 1 Introduction This information paper serves as an introduction to the major Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief (HADR) and Search and Rescue (SAR) organizations in Taiwan and international organizations working with Taiwanese government organizations or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in HADR. The paper is divided into two parts: The first section focuses on major International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs), and local NGO partners, as well as international Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) working in HADR in Taiwan or having provided -

Multilevel Spatial Impact Analysis of High-Speed Rail and Station Placement: a Short-Term Empirical Study of the Taiwan HSR

T J T L U http://jtlu.org V. 13 N. 1 [2020] pp. 317–341 Multilevel spatial impact analysis of high-speed rail and station placement: A short-term empirical study of the Taiwan HSR Yu-Hsin Tsai Jhong-yun Guan National Chengchi University Dept. of Urban Development, Taipei City [email protected] Government [email protected] Yi-hsin Chung Dept. of Urban Development, Taipei City Government [email protected] Abstract: Understanding the impact of high-speed rail (HSR) services Article history: on spatial distributions of population and employment is important for Received: September 15, 2019 planning and policy concerning HSR station location as well as a wide Received in revised form: May range of complementary spatial, transportation, and urban planning 14, 2020 initiatives. Previous research, however, has yielded mixed results into the Accepted: May 26, 2020 extent of this impact and a number of influential factors rarely have been Available online: November 4, controlled for during assessment. This study aims to address this gap 2020 by controlling for socioeconomic and transportation characteristics in evaluating the spatial impacts of HSR (including station placement) at multiple spatial levels to assess overall impact across metropolitan areas. The Taiwan HSR is used for this empirical study. Research methods include descriptive statistics, multilevel analysis, and multiple regression analysis. Findings conclude that HSR-based towns, on average, may experience growing population and employment, but HSR-based counties are likely to experience relatively less growth of employment in the tertiary sector. HSR stations located in urban or suburban settings may have a more significant spatial impact. -

107Annualreport.Pdf

灇涮鑑뀿䎃㜡 䎃䏞 2018 Research & Testing Annual Report ᢕ ヅ Ի ҝ ש ᭔ࣀ᱿ᅞೣŊဏۧהדŘ˫ໞل〵ꨶⰗ竸ざ灇瑖䨾 ͐ȭȭ 5BJXBO1PXFS3FTFBSDI*OTUJUVUF ͧḽሳघҀᱹଭト᱿ỻહヅԻȯ 5BJXBO1PXFS$PNQBOZ ㆤȭȭᇓŘໞᣅ֟⬤ʈϊവΒ⫯᱿ʊ᮹₤ヅԻ 䎃剢 ʶᏈゝߨȯ ൳Ř⦞ΒȮ〦໊ȮሺՖȮໞȯ ⻞ (Contents) ɺȮᶇᱹ⥶㊹ከᐉ ....................................... 6 ʷȮᶇἄᱹଭʙ⣬ໞኞ ................................... 8 ɺ ) ဏ֗ҝ⋱Ի ) ヅҝᇜ⪮ᮟᓏᾷໞኞջ⤺ᯉ ............................. 8ש .1 ヅҝʠ⣳Ԭᶇἄ ...... 10ڰヅʶᏈⵒⱧࠣᣅⱚⶪڰヅҝⱚͧヅ⎞ⶪש .2 ヅҝⱧࠣ⊵ᕒҝʠ⣳Ԭᶇἄ .............................. 12ש .3 Ҫᮝ⋱͆ℐ⣳ᑁଃ₇⃥Јᮢૌ⸇᪓ʠഛㅨ .................... 14 .4 16 ............................ שᏈ౹̳דջ⠗ⰿՀሺՖ̒ᾰᑨӼ .5 6. ᛧଇ⠧ᥨᮢऑખଊஉᮢヅ∌᳷कծԡาʠᶇἄ .................... 18 ( ʷ ) Ⳗ᭔ࣀΎ⩂⎞⫏ሷᄓӴᮢ ʷᖒջᷦ߸⫨ૺએ⥶㊹ᢆᘜࢍ֒߸⫨⋍ᇓᲶᛵ ...................... 20 .1 ʷᖒջؚᷦᄇԵҪᮝ⋱≩⎞༬⠛⤽ ............................ 22 .2 ʷᖒջᷦߗ๗ؚえԵᄊ⫨ඖ⋱ᶇἄ ................................ 24 .3 ʷᖒջᷦྐྵゝؚᄇᘍଜᖎʠ᭔ࣀഛㅨᶇἄӠኔ ...................... 26 .4 ʷᖒջᷦᖎ㋤ӠサỄʠ⩐ࣱؚえᘍᶇἄ .......................... 28 .5 ἼㆺԻᑨ┤ᦸʠⲻడỄ⎞Δ⩂⥫̒༬⠛ ........................ 30 .6 ඖ⥫̒ .................. 32⠗ר⬢⸅ԻᅩⱧಉ₇⃥ະᮢᅠʷᖒջᷦྐྵゝ .7 ⬢⎈᮹ᑨؐᖗᖛ⎞⌉ᶵᙹᖛʠ⚠⇦ᶇἄ ........................ 34 .8 9. ᤨᢝघҀջҪӴᮢᶇἄ .......................................... 36 ᤞ⌉ᶵᖛ ........................ 38דඖ⠗רヅೇザ⚠ᖛߊᄇ .10 ᙙඖᾷ .................. 40דⳭᱹヅೇᥣᤨᑨ SCR ⤯ඖ⋱ᒑᛵ⎟ .11 ᶇἄ ....... 42דⳭヅೇᱹヅ⥑ᅡㅷહ߸֡ϳ 22 ҝㅬ㏝ㆩ፷߸ⳍ⎟ .12 ᮢ౺く⥫̒༬⠛ᶇᱹ ..... 44͐דℬ ACSR ከἇ㋤⌜❘⸇ջᒑᛵ↿⺭␓⻘ .13 ቅなʀㆺᑨࢡಚ⌜❘Ծջ⥫̒ .......................... 46 1-3 דサ .14 Ѳ⋱༬⠛ະᮢדɿ ) Ւ̥ᷦᱹヅ ) 1. ᖎ⩽ㅷࢊ⫏⤻ະᮢᅠҪᮝ⋱ᱹヅㅷᛵʠ⥫̒ᶇἄ .................. 48 2. Ἴᖁ⿵ㆺࢍӛԻㅷᛵ⫏⤻₇⃥ .................................. 50 3. ᶇ᭼₤ߗ๗ᖒջᥣᅆヅᖷ (SOFC) ᱹヅ₇⃥ቅᄓ⋱૪ᛵ⥫̒ ... 52 ヅㆺࢍㆺԻᱹヅㅷᛵᄓ⋱ᄊۧ⥫̒ᶇἄ .......................... 54ש .4 1 ሩᅘ⣳Ԭ⥑⤺ ............................ 56דठぬ҆ヅࡣ₇⃥ი .5 ㆺԻᱹヅᑨ⳥Ⱨ྆ᐻʠἼ ................................ 58 .6 ( ߈ ) ԽᮢὉʠヅ⋱ᾷ⎞ሺՖ ʠᑁೣ⥫̒⎞ḻ ........ 60שᖁҪᮝ⋱ᱹヅ⸇֯ᆹ⫏⤻Ҙ⦲ಙ౹ .1 - ᇜℂḽ֒⎞ଡ⋱ᾷ₇⃥ (HEMS) ᄮະᮢᶇἄ .2 Ⳮヅೇ્⎤֒ᣅ͛ .......................................... 64⎟˫ ջ⎞ἇ⦲⪭ⰶ༸̥ᾷ૪㊹₇⃥⥫̒⎞ḻ ... -

Communiqué No

Taiwan Communiqué Published by: Formosan Association for Public Affairs 552 7th St. SE, Washington, D.C. 20003 Tel. (202) 547-3686 International edition, April / May 2013 Published 5 times a year 141 ISSN number: 1027-3999 Congressmen visit President Chen in jail On 2 May 2013, two prominent U.S. Congressmen, Mr. Steve Chabot (R-OH) and Mr. Eni Valeomavaega (D-Samoa) visited former President Chen in his cell in Pei-teh prison hospital Taichung, in central Taiwan. Chabot serves as the Chairman of the Subcommit- tee Asia & Pacific in the House Foreign Affairs Committee, while Valeomavaega is the Ranking Member. The visit came on the heels of Chen’s sudden transfer from the Veteran’s General Hospital in Taipei to the prison in Taichung on 19 April 2013 (see below). After the visit to Taichung, the Congressmen expressed concern about Chen’s health condition, and urged that Chen’s human rights should be respected. Chabot stated: “we think there is a humanitarian way to resolve the situation, and we would like to see that happen.” The visit came after several Photo: Liberty Times tumultuous weeks, which saw a groundswell of expressions of support for medical parole for Chen, both in Taiwan itself and overseas. This was supple- mented by medical reports from the team treating him at Taipei Veterans General Hospital TVGH), indicating that the best solution would be home care or treatment in a hospital near his home in Kaohsiung, which would have a specialized Congressmen Chabot and Faleomavaega after their psychiatry department. visit to Chen Shui-bian in Pei-teh Prison Hospital Taiwan Communiqué -2- April / May 2013 This led to the general expectation that the Ministry of Justice of the Ma government would grant a medical parole in the near future.