Temple Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

134TH COMMENCEMENT James E

134 th Commencement MAY 2021 Welcome Dear Temple graduates, Congratulations! Today is a day of celebration for you and all those who have supported you in your Temple journey. I couldn’t be more proud of the diverse and driven students who are graduating this spring. Congratulations to all of you, to your families and to our dedicated faculty and academic advisors who had the pleasure of educating and championing you. If Temple’s founder Russell Conwell were alive to see your collective achievements today, he’d be thrilled and amazed. In 1884, he planted the seeds that have grown and matured into one of this nation’s great urban research universities. Now it’s your turn to put your own ideas and dreams in motion. Even if you experience hardships or disappointments, remember the motto Conwell left us: Perseverantia Vincit, Perseverance Conquers. We have faith that you will succeed. Thank you so much for calling Temple your academic home. While I trust you’ll go far, remember that you will always be part of the Cherry and White. Plan to come back home often. Sincerely, Richard M. Englert President UPDATED: 05/07/2021 Contents The Officers and the Board of Trustees ............................................2 Candidates for Degrees James E. Beasley School of Law ....................................................3 Esther Boyer College of Music and Dance .....................................7 College of Education and Human Development ...........................11 College of Engineering ............................................................... -

Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Disability Rights and Independent Living Movement Oral History Project Thomas K. Gilhool LEGAL ADVOCATE FOR DEINSTITUTIONALIZATION AND THE RIGHT TO EDUCATION FOR PEOPLE WITH DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES Interviews conducted by Fred Pelka 2004-2008 Copyright © 2010 by The Regents of the University of California ii Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Thomas K. Gilhool, dated April 6, 2005. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

Susquehanna University Bulletin

COURSE CATALOG 2015–2016 SUSQUEHANNA UNIVERSITY BULLETIN SUSQUEHANNA UNIVERSITY BULLETIN GENERAL CATALOG FOR 2015-16 School of Arts and Sciences Sigmund Weis School of Business www.susqu.edu/catalog The 158th Academic Year 514 University Ave. Selinsgrove, PA 17870-1164 1 Mission. Susquehanna University educates undergraduate students for productive, creative and reflective lives of achievement, leadership and service in a diverse and interconnected world. Accreditation. Susquehanna University is accredited by the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, 3624 Market St., Philadelphia, PA 19104 (267-284-5000). The Middle States Commission on Higher Education is an institutional accrediting agency recognized by the U.S. Secretary of Education and the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA). The Sigmund Weis School of Business is accredited by AACSB International, a specialized accrediting organization recognized by the CHEA. Programs for the preparation of elementary and secondary education teachers at the bachelor's level are approved by the Pennsylvania Department of Education. The Department of Music is accredited by the National Association of Schools of Music, and the Department of Chemistry is accredited by the American Chemical Society. In addition, graduates in accounting are eligible to sit for the New York State licensure examination in Certified Public Accounting. Susquehanna is also a member of the American Association of Colleges and Universities, American Council on Education, Council of Independent Colleges, Annapolis Group, National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities, and Lutheran Educational Conference of North America. Nondiscrimination Statement. In administering its affairs, the university shall not discriminate against any person on the basis of race, color, religion, national or ethnic origin, ancestry, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, disability, veteran status, or any other legally protected status. -

Supreme Court Nomination - Letters to the President” of the Richard B

The original documents are located in Box 11, folder “Supreme Court Nomination - Letters to the President” of the Richard B. Cheney Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 11 of the Richard B. Cheney Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library .§n:prtlttt <!Jomt trf tltt ,-mtt.b- .§taftg Jfu£tittghtn. Jl. <!}. 2tl~'!~ CHAMBERS OF THE CHIEF .JUSTICE November 10, 1975 GONFiDEUTI:A:f::t Dear Mr. President: Against the possibility that a vacancy may occur on the Court there are certain factors, not always present when vacancies occur, that deserve consideration and I venture to submit them to you privately for such utility as they may have. (1) Rarely have the geographical factors been as neutral as at present. As you know, the two youngest Justices are from the West (White and Rehnquist); there are three from the Midwest (Burger, Stewart, Blackmun); one from a border state, Maryland (Marshall); one from the Northeast (Brennan); and one from the South (Powell). -

TRANSCRIPT of INTERVIEW with JUDGE ARLIN M. ADAMS 1. Gordon: I Am Sarah Gordon Here on July 1 1999 with Judge Arlin Adams Who Ha

TRANSCRIPT OF INTERVIEW WITH JUDGE ARLIN M. ADAMS 1. Gordon: I am Sarah Gordon here on July 1 1999 with Judge Arlin Adams who has kindly agreed to participate in the Oral Legal History Project at the University of Pennsylvania Law School. The interview is being conducted in his office at the Law Firm of Schnader, Harrison, Segal and Lewis at 1600 Market Street in Philadelphia. First of all Judge, let me tell you what a pleasure it is to see you today and I want to thank you for giving us your time. 2. Adams: My pleasure, I can assure you. 3. Gordon: If I could, I'd like to begin at the beginning with your childhood in Philadelphia. Could you tell us first when you were born and where have lived? 4. Adams: I was born in 1921. World War One was over. We lived in an area that was known as Central North Philadelphia, a very good neighborhood at that time. It had many people of German extraction who worked in the hosiery mills, many hosiery mills, printing plants and particularly the hat industry. Stetson was very big all over the United States and they had their big plants in Philadelphia. They were enormous. 5. Gordon: What did your parents do? 6. Adams: My father had been an artist. He had gone to the Pennsylvania Academy of Art. But in those days artists couldn't make a living and he drifted into the hat business, mainly because of Stetson. 7. Gordon: Did your mother work as well? 8. -

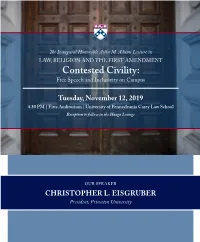

Contested Civility: Free Speech and Inclusivity on Campus

The Inaugural Honorable Arlin M. Adams Lecture in LAW, RELIGION AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT Contested Civility: Free Speech and Inclusivity on Campus Tuesday, November 12, 2019 4:30 PM | Fitts Auditorium | University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School Reception to follow in the Haaga Lounge OUR SPEAKER CHRISTOPHER L. EISGRUBER President, Princeton University THE HONORABLE ARLIN M. ADAMS The Honorable Arlin M. Adams was a leader on the bench, in government and in the community during an iconic career that spanned well over fifty years. His career took him from Schnader, Harrison, Segal & Lewis to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit to positions as a mediator on complex issues involving corruption and bankruptcy. Judge Adams graduated from Penn Law School in 1947 and never wavered in his affiliation to and support for the institution. He was elected editor- in-chief of the Law Review while a student and later taught at the law school. He also served as president of the Board of Overseers and delivered the Owen J. Roberts Lecture in 1987. Judge Adams is the namesake of the Arlin Adams Professorship in Constitutional Law and now the Hon. Arlin M. Adams Lecture on Law, Religion and the First Amendment. Born in Philadelphia in 1921, and raised during the Great Depression, Arlin M. Adams earned an undergraduate degree from Temple University and was the recipient of a full tuition scholarship to Penn Law School. In 1942, Adams took a leave of absence from the law school, enlisted in the U.S. Navy, and served in the North Pacific as a logistics officer. -

University of California, Santa Barbara

F O CA Y L IT I S F O R A R E N V I I A N LE , U T L University of California Santa Barbara IG T H T S H A E RE E A N B R T A A BARB Department of History Santa Barbara, California 93106-9410 Laura Kalman July 31, 2016 Dear Members of the NYU Legal History Colloquium: Thank you so much for agreeing to read my book manuscript! (And please do not copy, cite or circulate it without permission.) I have just submitted the manuscript (seconds ago) to Oxford for copy-editing, so I won’t be able to add any new chapters, based on what you tell me. But I will be able to make changes when the manuscript comes back from the copy-editor and before I submit the final version. It would ideal if you could make your criticisms as targeted/specific as possible so I know what to fix, massage, rewrite, add, delete, etc. But whatever you say, I really look forward to being with all of you again. Best wishes, Laura Kalman, Professor of History, UCSB 2 Colloquium on Constitutional & Legal History NYU School of Law August 31, 2016 The Long Reach of the Sixties: LBJ, Nixon and Supreme Court Nominations Laura Kalman [email protected] 805-453-8673 3 In Memory Of Newton Kalman, 1920-2010 Celeste Garr, 1924-2010 John Morton Blum, 1921-2011 Lee Kalman, 1919-2014 Protectors, Promoters, Teachers, Friends 4 Preface On February 13, 2016, friends found the body of the Supreme Court’s preeminent conservative in his suite at a hunting resort in West Texas. -

Law Alumni Journal: John W

et al.: Law Alumni Journal: John W. Nields, Jr. '67 THE LAW ALUMNI UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA Winter 1988 Volume XXIII Number 2 ~ ................ JOHN W. NIELDS, JR. '67 Chief Counsel to the U.S. House of Representatives' Select Committee to Investigate Covert Arms Transactions with Iran p. 7 THE IRVING R. SEGAL ·LECTURESHIP-----· IN TRIAL ADVOCACY: Hon. Simon H. Rifkind p. 13 THE RELIGION CLAUSES- ·THE-----· PAST AND THE FUTURE Roberts Lecture Hon. Arlin M. Adams'47 p. 9 In This Issue • FROM THE DEAN • ALUMNI PROFILE 12 • PUBUC ~TEREST 16 Published by Penn Law: Legal Scholarship Repository, 2014 SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAM 1 Penn Law Journal, Vol. 23, Iss. 2 [2014], Art. 1 The University of Pennsylvania does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, sex, sexual or affectional preference, age, relig ion, national or ethnic origin, or physical handicap. The University's policy applies to faculty and other employees, applicants FROM THE DEAN for faculty positions and other employment, students and applicants to educational pro grams. Contents Wide publicity has been FROM THE DEAN 1 given to a US. News and SYMPOSIUM 3 World &port poll of Law FEATURED EVENTS 7 John W Nields, Jr. '67 School deans which ranked Hon. Frank Easterbrook Visit this Law School 1Oth. Only "THE RELIGION CLAUSES 9 half of the deans questioned, THE PAST AND THE FUTURE" answered the questionnaire. Excerpts from the Hon. Arlin Adams' '47 Lecture In addition, I doubt that ALUMNI PROFILE 12 many deans, if any, know Featuring Howard L. Shecter '68 enough facts about other law THE IRVING R. -

Punishment in Prison: Constituting the “Normal” and the “Atypical” in Solitary and Other Forms of Confinement

Copyright 2020 by Judith Resnik, Hirsa Amin, Sophie Angelis, Megan Hauptman, Laura Kokotailo, Aseem Mehta, Madeline Silva, Tor Tarantola & Meredith Wheeler Printed in U.S.A. Vol. 115, No. 1 PUNISHMENT IN PRISON: CONSTITUTING THE “NORMAL” AND THE “ATYPICAL” IN SOLITARY AND OTHER FORMS OF CONFINEMENT Judith Resnik, Hirsa Amin, Sophie Angelis, Megan Hauptman, Laura Kokotailo, Aseem Mehta, Madeline Silva, Tor Tarantola & Meredith Wheeler ABSTRACT—What aspects of human liberty does incarceration impinge? A remarkable group of Black and white prisoners, most of whom had little formal education and no resources, raised that question in the 1960s and 1970s. Incarcerated individuals asked judges for relief from corporal punishment; radical food deprivations; strip cells; solitary confinement in dark cells; prohibitions on bringing these claims to courts, on religious observance, and on receiving reading materials; and from transfers to long- term isolation and to higher security levels. Judges concluded that some facets of prison that were once ordinary features of incarceration, such as racial segregation, rampant violence, and filth, violated the Constitution. Today, even as implementation is erratic and at times abysmal, correctional departments no longer claim they have unfettered authority to do what they want inside prisons walls. And, even as the courts have continued to tolerate the punishment of solitary confinement in the last decade, a few lower courts have held unconstitutional the profound sensory deprivations such isolation has entailed. -

Supreme Court Nomination - Background on Recommended Candidates” of the Richard B

The original documents are located in Box 11, folder “Supreme Court Nomination - Background on Recommended Candidates” of the Richard B. Cheney Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 11 of the Richard B. Cheney Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library • THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON MEMORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDENT THROUGH: RICHARD B. CHENEY FROM: DOUGLAS P. BENNETT~ SUBJECT: Candidates for the Supreme Court I. Comments. The following comments have been received by Phil Buchen or myself concerning the nomination to the Supreme Court. 1•. Jill Ruckelshaus, Audrey Colom (Chairman of the National Women's Political Caucus) and the National Federation of Business and Professional Women's Clubs strongly urge the appointment of a woman to the Supreme Court. 2. Harry Dent holds the firm belief that the appointee should be a conservative woman. 3. Roger Blough advised the nomination of an individual with a 11 middle of the road'' philosophy rather than a more conservative one. -

Introductory Material As Pdf

Materials Relating to Conduct of Attorneys in the Office of Independent Counsel Arlin M. Adams and Independent Counsel Larry D. Thompson in the Prosecution of Deborah Gore Dean (June 5, 2008; rev. July 26, 2008) Note: The materials made accessible through this page are quite voluminous. Even the narrative material on the page itself is substantial. Thus, although the narrative is organized in the way that I believe will be the most informative, I suggest the following to those readers who might not get too far into the narrative material in the normal course. Simply read the first four paragraphs of the Introduction. These provide a general background to the matter and should also at least suggest that something amiss occurred in the prosecution of United States of America v. Deborah Gore Dean. Then read Section B.1. At that point, put aside for the moment any feelings you might have that a group of federal prosecutors would never act in the described manner, much less under the direction of a distinguished jurist, and consider how you would regard the conduct of the involved Independent Counsel attorneys if the account is accurate and if the attorney ethics and morality reflected in this particular matter infused the entire prosecution. Then, in light of your view as to the nature of such conduct and the likelihood that the account is accurate, as well as your view of implications of the fact that persons involved with the prosecution would eventually hold high positions in the United States Department of Justice, consider whether you deem it worthwhile to read further. -

Justice Kavanaugh's Antitrust Testimony Before the Senate

Justice Kavanaugh’s Antitrust Testimony Before the Senate Judiciary Committee By Carl W. Hittinger and Jeanne-Michele Mariani As some presidents can attest, U.S. Supreme Court Kavanaugh had little background in antitrust, unlike Justice justices are more likely to change their judicial Neil Gorsuch, his willingness to dissent from the majority in philosophies once appointed than any other nominee to these cases seemed to reflect a pro-merger attitude that the federal court system. favored business efficiency over government regulation. He also displayed in his dissents a sense of the law that As some presidents can attest, U.S. Supreme Court balks at some of the safeguards put in place to enforce justices are more likely to change their judicial healthy competition. At his confirmation hearing before philosophies once appointed than any other nominee the Senate Judiciary Committee on Sept. 5, before the to the federal court system. Most recently Justice David proceedings shifted to more personal topics, Sen. Amy Souter, the pick of President George H.W. Bush, was Klobuchar, Ranking Member of the Subcommittee on supposed to be a win for conservatism, but as time went Antitrust, Competition Policy and Consumer Rights, by, he aligned himself more and more closely with the left. briefly focused on antitrust issues in her questioning. She President Gerald Ford on and off lamented his appointing called attention to Kavanaugh’s two antitrust dissents and antitrust expert Justice John Paul Stevens to the court. his hardly veiled disdain for two of the oldest and most The late great U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit formative Supreme Court decisions in antitrust law, Brown Judge Arlin Adams was his alternative choice.