DOCUMENT RESUME ED 080 566 TM 003 072 TITLE Changes In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

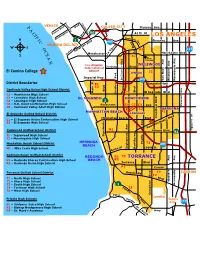

Distric Map.9

L Centinela in VENICE c CULVER CITY P o Blvd Slauson Ave. l A n C 90 64 th St I Venice Blvd F Blvd LOS ANGELES Cen Washington tinela N I Ave C 1 405 Florence Ave MARINA DEL REY W E O Brea r 110 e P3 C v Jefferson Blvd l La u Manchester Blvd E C Manchester La Tijera S A I1 The N Forum Los Angeles INGLEWOOD International Century Blvd El Camino College Airport I2 LENNOX Imperial Hwy La Cienega Blvd Normandie Ave 105 Van Ness Ave Western Ave District Boundaries E1 Imperial Hwy E2 Centinela Valley Union High School District Blvd Blvd Main St El Segundo Blvd Aviation Blvd C1 C1 – Hawthorne High School C2 – Lawndale High School EL SEGUNDO HAWTHORNE C3 – Leuzinger High School 1 C4 – R.K. Lloyd Continuation High School Rosecrans C4 C2 C5 Ave Vermont Ave C5 – Centinela Valley Adult High School C3 GARDENA MANHATTAN BEACH P1 El Segundo Unified School District LAWNDALE Manhattan Beach Blvd Crenshaw Blvd E1 – El Segundo Arena Continuation High School E2 – El Segundo High School Redondo Beach Blvd Inglewood Unified School District M1 Figueroa St Artesia Blvd 91 I1 – Inglewood High School Sepulveda I2 – Morningside High School HERMOSA Manhattan Beach School District Prairie T1 Ave BEACH 405 Inglewood Ave M1 – Mira Costa High School Hawthorne 190th St Anita St Redondo Beach Unified School District REDONDO R1 T5 TORRANCE R1 – Redondo Shores Continuation High School BEACH R2 R2 – Redondo Union High School Torrance Blvd P2 Carson T4 Torrance Unified School District Sepulveda CARSON T2 B T1 – North High School lvd T2 – Shery High School Western Ave T3 – South High School 1 Normandie Ave T4 – Torrance High School P T3 ac if T5 – West High School ic Palos Crenshaw Blvd C Lomita Private High Schools V o erd a Harbor e s 110 s t City P1 – Junipero Serra High School D P2 – Bishop Montgomery High School r P3 – St. -

Land Use Element Designates the General Distribution and Location Patterns of Such Uses As Housing, Business, Industry, and Open Space

CIRCULATION ELEMENT CITY OF HAWTHORNE GENERAL PLAN Adopted April, 1990 Prepared by: Cotton/Beland/Associates, Inc. 1028 North Lake Avenue, Suite 107 Pasadena, California 91104 Revision Table Date Case # Resolution # 07/23/2001 2001GP01 6675 06/28/2005 2005GP03 & 04 6967 12/09/2008 2008GP03 7221 06/26/2012 2012GP01 7466 12/04/2015 2015GP02 7751 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page I. Introduction to the Circulation Element 1 Purpose of this Element 1 Relation to Other General Plan Elements 1 II. Existing Conditions 2 Freeways 2 Local Vehicular Circulation and Street Classification 3 Transit Systems 4 Para-transit Systems 6 Transportation System Management 6 TSM Strategies 7 Non-motorized Circulation 7 Other Circulation Related Topics 8 III. Issues and Opportunities 10 IV. Circulation Element Goals and Policies 11 V. Crenshaw Station Active Transportation Plan 23 Circulation Element March 1989 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page Figure1: Street Classification 17 Figure 2: Traffic Volume Map 18 Figure 3: Roadway Standards 19 Figure 4: Truck Routes 20 Figure 5: Level of Service 21 LIST OF TABLES Table 1: Definitions of Level-of-Service 22 Circulation Element March 1989 SECTION I - INTRODUCTION TO THE CIRCULATION ELEMENT Circulation and transportation systems are one of the most important of all urban systems in determining the overall structure and form of the areas they service. The basic purpose of a transportation network within the City of Hawthorne is the provision of an efficient, safe, and serviceable framework which enables people to move among various sections of the city in order to work, shop, or spend leisure hours. -

For the First Time in Sunny Hills History, the ASB Has Added a Freshman, Sophomore and Junior Princess to the Homecoming Court

the accolade VOLUME LIX, ISSUE II // SUNNY HILLS HIGH SCHOOL 1801 LANCER WAY, FULLERTON, CA 92833 // SEPT. 28, 2018 JAIME PARK | theaccolade Homecoming Royalty For the first time in Sunny Hills history, the ASB has added a freshman, sophomore and junior princess to the homecoming court. Find out about their thoughts of getting nominated on Fea- ture, page 8. Saturday’s “A Night in Athens” homecoming dance will be held for the first time in the remodeled gym. See Feature, page 9. 2 September 28, 2018 NEWS the accolade SAFE FROM STAINS Since the summer, girls restrooms n the 30s wing, 80s wing, next to Room 170 and in the Engineer- ing Pathways to Innovation and Change building have metallic ver- tical boxes from which users can select free Naturelle Maxi Pads or Naturelle Tampons. Free pads, tampons in 4 girls restrooms Fullerton Joint Union High School District installs metal box containing feminine hygiene products to comply with legislation CAMRYN PAK summer. According to the bill, the state News Editor The Fullerton Joint Union government funds these hygiene High School District sent a work- products by allocating funds to er to install pad and tampon dis- school districts throughout the *Names have been changed for pensers in the girls restrooms in state. Then, schools in need are confidentiality. the 30s wing, the 80s wing, next able to utilize these funds in order It was “that time of month” to Room 170 and in the Engineer- to provide their students with free again, and junior *Hannah Smith ing Pathways to Innovation and pads and tampons. -

A Taxonomy of Exemplary Secondary School Programs in the State of California

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 089 710 IR 000 422 AUTHOR Davis, Emerson; ay, Richard TITLE A Taxonomy of ExOmplary Secondary School Programs in the State of California. INSTITUTION .California Stateliniv., Fullerton. School of Education. SPONS AGENCY Association of California School Administrators. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 217p.; Master's Thesis submitted to the California State University, Fullerton EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$10.20 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Alternative Schools; Career Education; Curriculum; *Educational Innovation; *Educational Programs; Indexes (Locaters); Information Dissemination; Information Retrieval; information Systems; *Innovation; Instruction; Instructional Innovation; Management; Masters Theses; Program Descriptions; Secondary Grades; *Secondary Schools; Special Education; *Taxonomy; Vocational Education IDENTIFIERS *California ABSTRACT A research project undertook to develop a system whereby information could be exchanged about exemplary secondary school programs within California. A survey was sent to 375 randomly selected districts throughout the State requesting information about model programs dealing with any of the following: curriculum, staffing patterns, office organization, gifted programs, slow learner programs, programs for the emotionally disturbed, individualized learning, advisory committees, career and vocational education, the use of department chairmen, or other innovative programs. The returned data were organized into a taxonomy of educational programs in order to facilitate easyAetrieval. The six major categories of 1) alternative education, 2) career-vocational education, 3) curriculum, 4) instructional techniques, 5) management, and 6) special education were developed; subcategories were constructed for each of the foregoing and programs arranged alphabetically in each class. Each of the more than 800 citations in the taxonomy supplies information on the program's title, a description of its features, the district's name, location and chief characteristics, and the person to contact for additional details. -

WASC 2019 Self-Study Report

1 I PREFACE The North Orange County Regional Occupational Program (NOCROP) 2019 WASC Self-Study Process has been a collaborative effort over the last eighteen months involving various stakeholders. During this time, the WASC Leadership Team facilitated opportunities to reflect on NOCROP’s mission of student success and the Career Technical Education experience we offer. NOCROP’s self-study process began in October 2017 with the review of accreditation criteria by Dana Lynch, Assistant Superintendent of Educational Services. In December 2017, the WASC Executive Team was formed to facilitate the process and Jennifer Prado, Patient Care Pathways Instructor was selected to serve as the 2019 Self-Study Coordinator. The self-study process was officially launched with a WASC Executive Team Meeting in February 2018, where Focus Group Chairs and Co-Chairs were assigned, and timelines were established. Focus Group work related to students and instruction commenced via Professional Learning Community (PLC) meetings during March, April, and May 2018. Individual meetings for the remaining Focus Groups were held during those same months. The focus on reviewing data and reflecting on its meaning has become more important and work was started early. The Educational Services Department provided data updates to instructional staff at the start of PLC meetings and guided them to reflect on its meaning, impact on them individually, and impact to the organization. Further review of data took place during NOCROP’s Back-to- School In-Service in August 2018 and at Spring In-Service in January 2019, which resulted in the implications identified in Chapter 1 of this document. -

South County Trojans Elite Youth Football Names Rich Trujillo Head Coach of Its 8U Division

Media Contact: Damon Elder Spotlight Marketing Communications FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 949.427.1377 [email protected] South County Trojans Elite Youth Football Names Rich Trujillo Head Coach of its 8U Division Trujillo has significant experience at both high school and club youth levels, including Trinity League and other regional high schools MISSION VIEJO, Calif. (Apr. 11, 2019) – The board of directors of South County Trojans Elite Youth Football announced today it has named Rich Trujillo as head coach if its 8U football team. “Coach Trujillo is a demonstrated leader who brings significant experience coaching both high school and club-level youth football,” said Chad Johnson, chairman of the Trojans’ board and head coach of the Mission Viejo High School football team. “His coaching career includes more than a decade at the elite youth level, where he helped lead numerous teams to championships, including the division’s Super Bowl. He works hard to elevate every athlete on his team, and we are very excited to have him lead the South County Trojans’ 8U division.” Coach Trujillo played as a linebacker and defensive end for Anaheim’s Western High School, where he was a varsity starter all four years. As a youth, he played for several years with both the Anaheim and Cypress Pop Warner programs. Coach Trujillo’s impressive coaching history at both the high school and elite youth levels include: • Orange Lutheran High School, varsity defensive line coach and freshman team’s defensive coordinator; • Servite High School, defensive line coach, freshman team, three years; • Buena Park High School, defensive line coach, freshman team. -

INGLEWOOD UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT 2018-2023 STRATEGIC PLAN the Inglewood Graduate: Ready from Day One!

INGLEWOOD UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT 2018-2023 STRATEGIC PLAN The Inglewood Graduate: Ready from Day One! Plan Updated: November 2018 Inglewood, California Content ONE Who We Are 04 TWO Executive Summary 08 The Inglewood Graduate: Ready from Day One! THREE Our Planning Process: • Moving Forward Together to Transform our Schools 10 FOUR Where We Are Now: Assessing Our Current State 13 FIVE Highlights of Our Strategic Plan 23 • Equity Principle, Mission, Core Beliefs 24 • Goals and Measures of Student Progress 25 • Our 2023 Commitments 26 • Our Four Pillars 27 • Professional Practices for Instructional Effectiveness 28 • Aligning the Instructional Core 29 • Our Roadmap: Twelve Strategic Priorities 30 SIX Implementing Our Strategic Plan • Paying Attention to Our Intention 35 • Setting Annual Performance Objectives 36 • Roadmap for Disciplined Implementation 37 SEVEN Appendix 41 • Members, Instructional Effectiveness Team 42 • Board of Education 43 02 A Blueprint for Our Students’ Future Inglewood is a school district recognized for its history, grit, and determination – qualities that have brought forth the resurgence of the Inglewood Unified School District (IUSD). It’s celebrated past has produced scientists, engineers, teachers, champion professional athletes, and many other accomplished citizens. IUSD has always been and will continue to be a place where students come to succeed. It’s no secret that over the past ten year years the job of providing a quality education that meets the needs of all IUSD students has been inconsistent. There have been many shifting trends in the community. And while our community has changed significantly in recent years, the mission of our school system remains unchanged: To provide equitable opportunities for every scholar to acquire . -

Ánimo Charter High School 12 a California Public Charter School

Ánimo Charter High School 12 A California Public Charter School Request for Five-Year Term July 1, 2017 to June 30, 2022 Submitted to Inglewood Unified School District October 7, 2016 Appeal Approved by Los Angeles County Office of Education March 14, 2017 for a Three-Year Term July 1, 2017 to June 30, 2020 Table of Contents Assurances and Affirmations ........................................................................................................................ 3 Element 1: The Educational Program ........................................................................................................... 5 Element 2: Measureable Pupil Outcomes and Element 3: Method by which Pupil Progress Toward Outcomes will be Measured ................................................................................................................................................ 85 Element 4: Governance ............................................................................................................................. 104 Element 5: Employee Qualifications ........................................................................................................ 118 Element 6: Health and Safety Procedures ................................................................................................. 134 Element 7: Means to Achieve Racial and Ethnic Balance ........................................................................ 137 Element 8: Admissions Requirements ..................................................................................................... -

® for Better Education Por Una Mejor Educación

FREE Education + Communication = A Better Nation ® Covering the Inglewood Unified School District VOLUME 1, ISSUE 1 MARCH / APRIL 2015 Strong Community Partnerships Las Asociaciones Comunitarias Sólidas Contribute to IUSD’s Success Contribuyen al Éxito de IUSD By Kristin Agostoni By Kristin Agostoni The Inglewood Unified School Las vacaciones de invierno apenas District (IUSD) winter break had habían comenzado en el Distrito just begun when hundreds of Unificado de Inglewood cuando families converged on the campus of cientos de familias convergieron Morningside High School. en el campo escolar de la escuela The school opened its doors that secundaria Morningside. Saturday in December not for class La escuela abrió sus puertas but for a special event organized by ese sábado en diciembre, no por the nonprofit St. Margaret’s Center. clases, sino por un evento especial School and district employees, organizado por el centro sin fines de working around the clock with lucro St. Margaret. Los empleados de volunteers from the organization las escuelas y del distrito, trabajaron that helps local families in need, contra el reloj con los voluntarios de had transformed the campus into a esa organización para ayudar a las Winter Wonderland, inviting parents familias necesitadas de la localidad; to select gifts for their children while transformaron el campo escolar en the youngsters enjoyed food and una Tierra de Maravilla de Invierno, holiday fun. invitando a los padres de familia a IUSD’s participation in the Members of the 2014 UCLA Women’s National Championship Tennis Team seleccionar regalos para sus niños, hosted a tennis clinic for students of all ages at Inglewood High. -

CLASS SCHOOL SCORE Saturday, March 17, 2018 2018

Saturday, March 17, 2018 2018 Westminster High School @ Westminster High School in Westminster, California Winter Guard Association of Southern California (WGASC) CLASS SCHOOL SCORE JH AAA Brea Junior High School 46.80 JH AA Bellflower Middle School (JV) 69.11 JH AA Kraemer Middle School 64.36 JH AA Travis Ranch Middle School 60.13 JH AA Canyon Hills Middle School 56.99 JH AA Tuffree Middle School #1 56.30 JH A Bellflower Middle School (Varsity) 72.73 JH A Ross Middle School 70.49 JH A Alvarado Intermediate 69.16 JH A Lisa J. Mails Elementary School 64.39 HS AA Brea Olinda High School (Varsity) 68.58 HS AA Segerstrom High School 65.39 HS AA Santiago High School (GG) 61.98 HS AA Laguna Hills High School 58.49 HS AA Anaheim High School 57.76 HS AA Buena Park High School 55.15 HS AA Santa Fe High School #2 54.98 HS AA Lakewood High School 50.76 HS AA Fullerton Union High School 47.89 HS A - Round 1 California High School 73.50 HS A - Round 1 Tesoro High School 72.70 HS A - Round 1 Troy High School 70.88 HS A - Round 1 Westminster High School (JV) 69.98 HS A - Round 1 Sunny Hills High School #2 68.71 HS A - Round 1 Pacifica High School 67.39 HS A - Round 1 Santa Margarita Catholic High School 66.70 HS A - Round 2 Saddleback High School 63.84 HS A - Round 2 Western High School 76.71 HS A - Round 2 Duarte High School 74.20 HS A - Round 2 Bell High School 72.14 HS A - Round 2 Torrance High School 71.44 HS A - Round 2 Los Amigos High School 69.80 HS A - Round 2 Villa Park High School 68.93 HS A - Round 2 Santa Fe High School #1 68.48 Last Updated on 3/19/2018 at 12:00 PM Saturday, March 17, 2018 2018 Westminster High School @ Westminster High School in Westminster, California Winter Guard Association of Southern California (WGASC) CLASS SCHOOL SCORE SAAA - Round 1 San Marino High School 68.05 SAAA - Round 1 Glen A. -

Open Space Element Inglewood General Plan

OPEN SPACE ELEMENT INGLEWOOD GENERAL PLAN =================================================================== OPEN SPACE ELEMENT =================================================================== INGLEWOOD GENERAL PLAN DECEMBER 1995 Prepared by Community Development and Housing Department City of Inglewood One Manchester Boulevard Inglewood, California 90301 =================================================================== TABLE OF CONTENTS =================================================================== Purpose of the Open Space Element 1 Compatibility of Open Space Element with General Plan 2 Introduction 5 RECREATION FACILITIES I PARK LAND Need for Parks 6 Inventory of Inglewood Parks 9 Analysis of Park Needs 14 Southwest Inglewood Area 16 Lockhaven Area 24 Mini parks 27 Goals and Policies to Provide Parks 29 Implementation and Funding 32 OPEN SPACE (Nonpark Sites} Need for Open Space 38 Inventory of Open Space 39 Analysis of Open Space Preservation and Provision 47 Goal and Policies to Preserve and Provide Open Space 52 Implementation 54 References 55 DIAGRAMS Diagram 1. Vicinity Map Diagram 2. City Parks 10 Diagram 3. Recreational Parks Showing Service Radii 15 Diagram 4. Multiple-Unit Neighborhoods Outside Service Radii of Recreational Parks 17 Diagram 5. Possible Park Sites for Southwest Inglewood Area 19 Diagram 6. Possible Park Sites for Lockhaven Area 25 Diagram 7. Open Space Sites 40 APPENDICES Negative Declaration 57 City Council Resolution 58 1996 - 2006 AQUISITION PROGRAM 60 DOWNTOWN L.A. FREEWAY Kl NG LOS ANGELES SLAUSON -

` Santa Monica Community College District District Planning And

Santa Monica Community College District District Planning and Advisory Council MEETING – MARCH 13, 2019 AGENDA ` A meeting of tHe Santa Monica Community College District Planning and Advisory Council (DPAC) is scHeduled to be Held on Wednesday, MarcH 13, 2019 at 3:00 p.m. at Santa Monica College DrescHer Hall Room 300-E (tHe Loft), 1900 Pico Boulevard, Santa Monica, California. I. Call to Order II. Members Teresita Rodriguez, Administration, CHair Designee Nate DonaHue, Academic Senate President, Vice-Chair Mike Tuitasi, Administration Representative Eve Adler, Management Association President Erica LeBlanc, Management Association Representative Mitra Moassessi, Academic Senate Representative Peter Morse, Faculty Association President Tracey Ellis, Faculty Association Representative Cindy Ordaz, CSEA Representative Dee Upshaw, CSEA Representative Isabel Rodriguez, Associated Students President ItzcHak MagHen, Associated Student Representative III. Review of Minutes: February 27, 2019 IV. Reports V. Superintendent/President’s Response to DPAC Recommendations, if any. VI. Agenda Public Comments Individuals may address tHe District Planning and Advisory Council (DPAC) concerning any subject tHat lies witHin tHe jurisdiction of DPAC by submitting an information card with name and topic on which comment is to be made. The Chair reserves tHe rigHt to limit tHe time for each speaker. 1. Report: SMC Promise Program 2. Student Services Center Directory 3. DPAC Restructure/ScHedule • Chief Director of Business Services Chris Bonvenuto will attend