Eucyclogobius Newberryi)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Propoxur United States Environmental Protection Agency

United States Prevention, Pesticides EPA738-R-97-009 Environmental Protection And Toxic Substances August 1997 Agency (7508W) Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) PROPOXUR UNITED STATES ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY WASHINGTON, D.C. 20460 OFFICE OF PREVENTION, PESTICIDES AND TOXIC SUBSTANCES CERTIFIED MAIL Dear Registrant: I am pleased to announce that the Environmental Protection Agency has completed its reregistration eligibility review and decisions on the pesticide chemical case propoxur. The enclosed Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) contains the Agency's evaluation of the data base of this chemical, its conclusions of the potential human health and environmental risks of the current product uses, and its decisions and conditions under which these uses and products will be eligible for reregistration. The RED includes the data and labeling requirements for products for reregistration. It may also include requirements for additional data (generic) on the active ingredient to confirm the risk assessments. To assist you with a proper response, read the enclosed document entitled "Summary of Instructions for Responding to the RED." This summary also refers to other enclosed documents which include further instructions. You must follow all instructions and submit complete and timely responses. The first set of required responses is due 90 days from the receipt of this letter. The second set of required responses is due 8 months from the date of receipt of this letter. Complete and timely responses will avoid the Agency taking the enforcement action of suspension against your products. If you have questions on the product specific data requirements or wish to meet with the Agency, please contact the Special Review and Reregistration Division representative Bonnie Adler (703) 308-8523. -

Determination of the Residual Efficacy of Carbamate and Organophosphate

Yewhalaw et al. Malar J (2017) 16:471 DOI 10.1186/s12936-017-2122-3 Malaria Journal RESEARCH Open Access Determination of the residual efcacy of carbamate and organophosphate insecticides used for indoor residual spraying for malaria control in Ethiopia Delenasaw Yewhalaw1,2†, Meshesha Balkew3†, Josephat Shililu4, Sultan Suleman5, Alemayehu Getachew4, Gedeon Ashenbo4, Sheleme Chibsa6, Gunawardena Dissanayake6, Kristen George7, Dereje Dengela8, Yemane Ye‑Ebiyo4 and Seth R. Irish9* Abstract Background: Indoor residual spraying is one of the key vector control interventions for malaria control in Ethiopia. As malaria transmission is seasonal in most parts of Ethiopia, a single round of spraying can usually provide efective protection against malaria, provided the insecticide remains efective over the entire malaria transmission season. This experiment was designed to evaluate the residual efcacy of bendiocarb, pirimiphos-methyl, and two doses of pro‑ poxur on four diferent wall surfaces (rough mud, smooth mud, dung, and paint). Filter papers afxed to wall surfaces prior to spraying were analyzed to determine the actual concentration applied. Cone bioassays using a susceptible Anopheles arabiensis strain were done monthly to determine the time for which insecticides were efective in killing mosquitoes. Results: The mean insecticide dosage of bendiocarb applied to walls was 486 mg/m2 (target 400/mg). This treat‑ ment lasted 1 month or less on rough mud, smooth mud, and dung, but 4 months on painted surfaces. Pirimiphos- methyl was applied at 1854 mg/m2 (target 1000 mg/m2), and lasted between 4 and 6 months on all wall surfaces. Propoxur with a target dose of 1000 mg/m2 was applied at 320 mg/m2, and lasted 2 months or less on all surfaces, except painted surfaces (4 months). -

Florida State Emergency Response Commission

Florida State Emergency Response Commission Sub-Committee on Training (SOT) HAZARDOUS MATERIALS MEDICAL TREATMENT PROTOCOLS Version 3.3 TOXIDROMES Toxidromes are clinical syndromes that the patient presents with. These patterns of signs and symptoms are essential for the successful recognition of chemical exposure. The toxidromes identified in this protocol are chemical exposure based while others such as the opioids are found within general medical protocol. These chemical toxidromes are identified clinically into five syndromes: Irritant Gas Toxidrome Asphyxiant Toxidrome Corrosive Toxidrome Hydrocarbon and Halogenated Hydrocarbons Toxidrome Cholinergic Toxidrome Each can present as a clinical manifestation of the chemical/poisoning involved with some cross-over between toxidromes. This list combines the toxic syndromes found within NFPA 473 (A.5.4.1(2) and traditional syndromes. Toxidrome Correlation to NFPA Standard 473 and Traditional Syndromes Toxidrome NFPA 473 A.5.4.1(2) Hazardous Materials Protocol Correlation Irritant Gas (j) Irritants Bronchospasm OC Pepper spray & lacrimants Asphyxiant (c) Chemical asphyxiants Carbon Monoxide (d) Simple asphyxiants Aniline dyes, Nitriles, Nitrares (h) Blood Agents Cyanide & Hydrogen Sulfide (n) Nitrogen Compounds Closed Space Fires Simple Asphyxants Corrosive (a) Corrosives Hydrofluroic Acid (g) Vesicants Chemical burns to the eye Choramine and Chlorine Hydrocarbon (e) Organic solvents Phenol and (q) Phenolic Compounds Halogenated Hydrocarbons Halogenated Hydrocarbons Cholinergic (b) Pesticides -

Chlorpyrifos, Part 1: Toxicology

JOURNAL OF PESTICIDE REFORM/ WINTER 1994 • VOL.14, NO. 4 ■ INSECTICIDE FACTSHEET CHLORPYRIFOS, PART 1: TOXICOLOGY The broad spectrum organophosphate insecticide chlorpyrifos is the most widely used insecticide in the U.S. Total use is estimated at almost 30 million pounds per year. Like all organophosphate insecticides, chlorpyrifos affects the nervous system by inhibiting an enzyme that is important in the transmission of nerve impulses. Symptoms of acute poisoning include headache, nausea, muscle twitching, and convulsions. Chlorpyrifos poisonings are reported to state and federal agencies more often than poisonings of almost every other insecticide. In both laboratory animals and humans, chlorpyrifos can also cause delayed effects on the nervous system. Some effects have been measured years after exposure. Human birth defects have been associated with exposure to chlorpyrifos products. In pregnant laboratory animals, chlorpyrifos exposure caused fetal death. Pups that did survive were smaller pups and did not survive as well as pups from unexposed mothers. Chlorpyrifos also affects the male reproductive system; exposure to a chlorpyrifos product has caused death of cells in male rat testes and a decrease in sperm production in cattle. Chlorpyrifos has caused genetic damage in human blood and lymph cells, mice spleen cells, and hamster bone marrow cells. Immune system abnormalities have been reported from patients exposed to chlorpyrifos. Many individuals report developing sensitivities to a broad array of substances following chlorpyrifos exposure. The second part of this factsheet will discuss human exposure to chlorpyrifos and the ecological effects of chlorpyrifos. BY CAROLINE COX mary agricultural uses are for oranges, al- plications are made annually. -

Agricultural Pesticide Use in New Jersey: 1997 Survey

NJ Pesticide Control Program Pesticide Control Program Pesticide Evaluation & Monitoring AGRICULTURAL PESTICIDE USE IN NEW JERSEY: 2003 SURVEY Introduction The New Jersey Pesticide Control Program (NJPCP) began a series of pesticide use surveys in 1985. These surveys address pesticide use in the state of New Jersey for agriculture, golf courses, termite control, right-of-way, mosquito control, and lawn care. The agricultural use survey is conducted every three years and targets agricultural, nursery, and greenhouse use of general and restricted pesticides. This report focuses on the seventh survey completed in this series (2003). All statewide pesticide use surveys are performed under the authority of the New Jersey Pesticide Control Code, N.J.A.C. 7:30-1 et.seq., requiring applicators to maintain pesticide records for two years and to submit use records to the state when requested. This regulative authority provides an accuracy and level of response that is difficult to duplicate in a voluntary, nationwide survey. In fact, these New Jersey surveys almost represent a pesticide usage census rather than a probabilistic survey. The information collected from the NJPCP pesticide use surveys is used by agencies within the NJ Department of Environmental Protection along with other state agencies to aid in research, exposure management and monitoring efforts in areas such as ground water protection, farm worker protection and education, and residual pesticide sampling. The survey data are also entered into state and federal geographical information systems for geographical distribution. Methods The NJPCP's registration records were used to identify all 2094 private applicators licensed as of December 2003. -

Table II. EPCRA Section 313 Chemical List for Reporting Year 2017 (Including Toxic Chemical Categories)

Table II. EPCRA Section 313 Chemical List For Reporting Year 2017 (including Toxic Chemical Categories) Individually listed EPCRA Section 313 chemicals with CAS numbers are arranged alphabetically starting on page II-3. Following the alphabetical list, the EPCRA Section 313 chemicals are arranged in CAS number order. Covered chemical categories follow. Note: Chemicals may be added to or deleted from the list. The Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Call Center or the TRI-Listed Chemicals website will provide up-to-date information on the status of these changes. See section B.3.c of the instructions for more information on the de minimis % limits listed below. There are no de minimis levels for PBT chemicals since the de minimis exemption is not available for these chemicals (an asterisk appears where a de minimis limit would otherwise appear in Table II). However, for purposes of the supplier notification requirement only, such limits are provided in Appendix C. Chemical Qualifiers Certain EPCRA Section 313 chemicals listed in Table II have parenthetic “qualifiers.” These qualifiers indicate that these EPCRA Section 313 chemicals are subject to the section 313 reporting requirements if manufactured, processed, or otherwise used in a specific form or when a certain activity is performed. An EPCRA Section 313 chemical that is listed without a qualifier is subject to reporting in all forms in which it is manufactured, processed, and otherwise used. The following chemicals are reportable only if they are manufactured, processed, or otherwise used in the specific form(s) listed below: Chemical/ Chemical Category CAS Number Qualifier Aluminum (fume or dust) 7429-90-5 Only if it is a fume or dust form. -

Chemical Hygiene Plan (CHP) Which Includes Laboratory Specific Hazard and Safety Information

University of Massachusetts Lowell Environmental and Emergency Management (EEM) Environmental Health and Safety (EHS) CHEMICAL HYGIENE PLAN Dates of Annual CHP Review and/or Dates of Revisions (EEM-EHS will complete this page, annually, after each CHP review or revision) Name (print) Signature Date Page 1 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 2 – SAFETY RESPONSIBILITIES................................................................................................ 4 CHAPTER 3 – EMERGENCY PROCEDURES ............................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER 4 – CHEMICAL HAZARD MANAGEMENT ............................................................................ 15 CHAPTER 5 – HAZARDOUS WASTE MANAGEMENT ............................................................................ 23 CHAPTER 6 – ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT AND STEWARDSHIP ........................................ 46 CHAPTER 7 – SAFETY TRAINING ............................................................................................................... 47 CHAPTER 8 – SAFE LABORATORY PRACTICES .................................................................................... 48 CHAPTER 9 – STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES ........................................................................ 53 CHAPTER 10 – PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPEMENT (PPE) ........................................................ -

Recent Advances on Detection of Insecticides Using Optical Sensors

sensors Review Recent Advances on Detection of Insecticides Using Optical Sensors Nurul Illya Muhamad Fauzi 1, Yap Wing Fen 1,2,*, Nur Alia Sheh Omar 1,2 and Hazwani Suhaila Hashim 2 1 Functional Devices Laboratory, Institute of Advanced Technology, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] (N.I.M.F.); [email protected] (N.A.S.O.) 2 Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang 43400, Selangor, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Insecticides are enormously important to industry requirements and market demands in agriculture. Despite their usefulness, these insecticides can pose a dangerous risk to the safety of food, environment and all living things through various mechanisms of action. Concern about the environmental impact of repeated use of insecticides has prompted many researchers to develop rapid, economical, uncomplicated and user-friendly analytical method for the detection of insecticides. In this regards, optical sensors are considered as favorable methods for insecticides analysis because of their special features including rapid detection time, low cost, easy to use and high selectivity and sensitivity. In this review, current progresses of incorporation between recognition elements and optical sensors for insecticide detection are discussed and evaluated well, by categorizing it based on insecticide chemical classes, including the range of detection and limit of detection. Additionally, this review aims to provide powerful insights to researchers for the future development of optical sensors in the detection of insecticides. Citation: Fauzi, N.I.M.; Fen, Y.W.; Omar, N.A.S.; Hashim, H.S. Recent Keywords: insecticides; optical sensor; recognition element Advances on Detection of Insecticides Using Optical Sensors. -

Gas-Phase Chemical Reduction (GPCR)

Gas-Phase Chemical Reduction (GPCR) Name of Process: Status: Gas-Phase Chemical Reduction (GPCR) A Commercial system operated in Australia for more than 5 years, treating Vendor: more than 2,500 tons of PCB’s, DDT and other POPs. In 1999 a full-scale test ELI Eco Logic International Inc. on HCB was conducted using the commercial plant. Web site: http://www.ecologic.ca Eco Logic’s partners in Japan have recently built a semi-mobile GPCR plant for Applicable Pesticides and related the treatment of PCB wastes, which will be operational in 2003. POPs wastes: Pesticides such as Hexachlorobenzene, In combination with Foster Wheeler and Kvaerner the company is DDT, Aldrin, Dieldrin, HCB’s, DDT, PCB’s, participating at present in the ACWA (Army Chemical Weapons Assessment) dioxins and furans and other POPs. Program for the destruction of chemical warfare agents. Eco Logic has partnered with Torftech Inc. for the treatment of soils and sediments at rates of up to 20 tons per hour. Eco Logic has also been selected by UNIDO for a pilot project for treatment of 1000 tons of PCB wastes in Slovakia. Additional approvals received: -for PCB and dioxin waste in Japan -for PCB’s TSCA permit in USA -for PCB’s and other toxic compounds in the Province of Ontario (Canada) Technology description: Eco Logic’s GPCR technology involves the gas-phase chemical reduction of organic compounds by hydrogen at a temperature of 850°C or higher. Chlorinated hydrocarbons, such as HCB, polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins (dioxins) and other POPs, are chemically reduced to methane and hydrogen chloride (HCl). -

Recommended Classification of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classification 2019 Theinternational Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) Was Established in 1980

The WHO Recommended Classi cation of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classi cation 2019 cation Hazard of Pesticides by and Guidelines to Classi The WHO Recommended Classi The WHO Recommended Classi cation of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classi cation 2019 The WHO Recommended Classification of Pesticides by Hazard and Guidelines to Classification 2019 TheInternational Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS) was established in 1980. The overall objectives of the IPCS are to establish the scientific basis for assessment of the risk to human health and the environment from exposure to chemicals, through international peer review processes, as a prerequisite for the promotion of chemical safety, and to provide technical assistance in strengthening national capacities for the sound management of chemicals. This publication was developed in the IOMC context. The contents do not necessarily reflect the views or stated policies of individual IOMC Participating Organizations. The Inter-Organization Programme for the Sound Management of Chemicals (IOMC) was established in 1995 following recommendations made by the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development to strengthen cooperation and increase international coordination in the field of chemical safety. The Participating Organizations are: FAO, ILO, UNDP, UNEP, UNIDO, UNITAR, WHO, World Bank and OECD. The purpose of the IOMC is to promote coordination of the policies and activities pursued by the Participating Organizations, jointly or separately, to achieve the sound management of chemicals in relation to human health and the environment. WHO recommended classification of pesticides by hazard and guidelines to classification, 2019 edition ISBN 978-92-4-000566-2 (electronic version) ISBN 978-92-4-000567-9 (print version) ISSN 1684-1042 © World Health Organization 2020 Some rights reserved. -

List of Lists

United States Office of Solid Waste EPA 550-B-10-001 Environmental Protection and Emergency Response May 2010 Agency www.epa.gov/emergencies LIST OF LISTS Consolidated List of Chemicals Subject to the Emergency Planning and Community Right- To-Know Act (EPCRA), Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) and Section 112(r) of the Clean Air Act • EPCRA Section 302 Extremely Hazardous Substances • CERCLA Hazardous Substances • EPCRA Section 313 Toxic Chemicals • CAA 112(r) Regulated Chemicals For Accidental Release Prevention Office of Emergency Management This page intentionally left blank. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction................................................................................................................................................ i List of Lists – Conslidated List of Chemicals (by CAS #) Subject to the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA), Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) and Section 112(r) of the Clean Air Act ................................................. 1 Appendix A: Alphabetical Listing of Consolidated List ..................................................................... A-1 Appendix B: Radionuclides Listed Under CERCLA .......................................................................... B-1 Appendix C: RCRA Waste Streams and Unlisted Hazardous Wastes................................................ C-1 This page intentionally left blank. LIST OF LISTS Consolidated List of Chemicals -

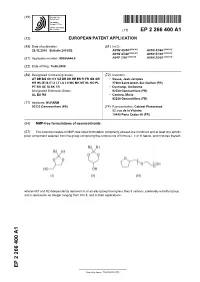

NMP-Free Formulations of Neonicotinoids

(19) & (11) EP 2 266 400 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 29.12.2010 Bulletin 2010/52 A01N 43/40 (2006.01) A01N 43/86 (2006.01) A01N 47/40 (2006.01) A01N 51/00 (2006.01) (2006.01) (2006.01) (21) Application number: 09305544.0 A01P 7/00 A01N 25/02 (22) Date of filing: 15.06.2009 (84) Designated Contracting States: (72) Inventors: AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GR • Gasse, Jean-Jacques HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO PL 27600 Saint-Aubin-Sur-Gaillon (FR) PT RO SE SI SK TR • Duchamp, Guillaume Designated Extension States: 92230 Gennevilliers (FR) AL BA RS • Cantero, Maria 92230 Gennevilliers (FR) (71) Applicant: NUFARM 92233 Gennevelliers (FR) (74) Representative: Cabinet Plasseraud 52, rue de la Victoire 75440 Paris Cedex 09 (FR) (54) NMP-free formulations of neonicotinoids (57) The invention relates to NMP-free liquid formulation comprising at least one nicotinoid and at least one aprotic polar component selected from the group comprising the compounds of formula I, II or III below, and mixtures thereof, wherein R1 and R2 independently represent H or an alkyl group having less than 5 carbons, preferably a methyl group, and n represents an integer ranging from 0 to 5, and to their applications. EP 2 266 400 A1 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) EP 2 266 400 A1 Description Technical Field of the invention 5 [0001] The invention relates to novel liquid formulations of neonicotinoids and to their use for treating plants, for protecting plants from pests and/or for controlling pests infestation.