THE MEANING of RAMA M. Ram Murty1 Long Before Plato

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antiquities of Madhava Worship in Odisha

August - 2015 Odisha Review Antiquities of Madhava Worship in Odisha Amaresh Jena Odisha is a confluence of innumerable of the Brihadaranayaka sruti 6 of the Satapatha religious sects like Buddhism, Jainism, Saivism, Brahman belonging to Sukla Yajurveda and Saktism, Vaishnavism etc. But the religious life of Kanva Sakha. It is noted that the God is realized the people of Odisha has been conspicuously in the lesson of Madhu for which he is named as dominated by the cult of Vaishnavism since 4th Madhava7. Another name of Madhava is said to Century A.D under the royal patronage of the have derived from the meaning Ma or knowledge rulling dynasties from time to time. Lord Vishnu, (vidya) and Dhava (meaning Prabhu). The Utkal the protective God in the Hindu conception has Khanda of Skanda Purana8 refers to the one thousand significant names 1 of praise of which prevalence of Madhava worship in a temple at twenty four are considered to be the most Neelachala. Madhava Upasana became more important. The list of twenty four forms of Vishnu popular by great poet Jayadev. The widely is given in the Patalakhanda of Padma- celebrated Madhava become the God of his love Purana2. The Rupamandana furnishes the and admiration. Through his enchanting verses he twenty four names of Vishnu 3. The Bhagabata made the cult of Radha-Madhava more familiar also prescribes the twenty four names of Vishnu in Prachi valley and also in Odisha. In fact he (Keshava, Narayan, Madhava, Govinda, Vishnu, conceived Madhava in form of Krishna and Madhusudan, Trivikram, Vamana, Sridhara, Radha as his love alliance. -

Pathanamthitta

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory PATHANAMTHITTA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 105 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at 2011 Census (b) -

Narrative, Public Cultures and Visuality in Indian Comic Strips and Graphic Novels in English, Hindi, Bangla and Malayalam from 1947 to the Present

UGC MRP - COMICS BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Narrative, Public Cultures and Visuality in Indian Comic Strips and Graphic Novels in English, Hindi, Bangla and Malayalam from 1947 to the Present UGC MAJOR RESEARCH PROJECT F.NO. 5-131/2014 (HRP) DT.15.08.2015 Principal Investigator: Aneeta Rajendran, Gargi College, University of Delhi UGC MRP INDIAN COMIC BOOKS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS Acknowledgements This work was made possible due to funding from the UGC in the form of a Major Research Project grant. The Principal Investigator would like to acknowledge the contribution of the Project Fellow, Ms. Shreya Sangai, in drafting this report as well as for her hard work on the Project through its tenure. Opportunities for academic discussion made available by colleagues through formal and informal means have been invaluable both within the college, and in the larger space of the University as well as in the form of conferences, symposia and seminars that have invited, heard and published parts of this work. Warmest gratitude is due to the Principal, and to colleagues in both the teaching and non-teaching staff at Gargi College, for their support throughout the tenure of the project: without their continued help, this work could not have materialized. Finally, much gratitude to Mithuraaj for his sustained support, and to all friends and family members who stepped in to help in so many ways. 1 UGC MRP INDIAN COMIC BOOKS AND GRAPHIC NOVELS Project Report Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1. Scope and Objectives 3 2. Summary of Findings 3 2. Outcomes and Objectives Attained 4 3. -

The Mysterious Controller of the Universe : Shri Neelamadhava - Shri Jagannath

ISSN 0970-8669 Odisha Review Madhava Madhava vacyam, Madhava madhava harih; Smaranti Madhava nityam, sarva karye su Madhavah. Towards the end of Lord Sri Rama’s regime in Tretaya Yuga, Sri Hanuman was advised by the Lord Sri Rama to remain immersed in meditation (dhyanayoga) in ‘Padmadri hill’ till his services would be recalled in Dwapar Yuga. When the great devotee, Sri Hanuman expressed his prayer as to how he would see his divine Master during such a long spell of time, the Lord advised him that he would be able to see his ever- The Mysterious Controller of the Universe : Shri Neelamadhava - Shri Jagannath Dr. K.C. Sarangi Lord, always desires His devotees to have cherished ‘Sri Rama’ in the form of Lord Sri equanimity in all circumstances: favourable or Neelamadhava whom he would worship in unfavourable, and to destroy their ingorance by ‘Brahmadri’, the adjacent hill and enjoy the the sword of conscience, ‘tasmat ajnana everlasting bliss ‘naisthikeem shantim’ as the sambhutam hrutstham jnanasinatmanah (Ch. IV, Gita describes (Ch.5, Verse 12). Sri Hanuman verse.42) and work in a detached manner was a sthitadhi. Those devotees, whose minds surrendering the fruit of all actions to the Lotus are equiposed, attend the victory over the world feet of the Lord so that the devotee does not during their life time. Since Paramatma the become partaker of the sins as the Lotus leaf is Almighty Father is flawless and equiposed, such not affected by water ‘brahmani adhyaya devotees rest in the lotus feet of the Lord karmani sangam tyaktwa karoiti yah, lipyate ‘nirdosam hi samam brahma tasmad na sa papena padmapatramivambasa’ (Ch.V, brahmani te sthitaah’, (ibid v.19). -

AP Reports 229 Black Fungus Cases in 1

VIJAYAWADA, SATURDAY, MAY 29, 2021; PAGES 12 `3 RNI No.APENG/2018/764698 Established 1864 Published From VIJAYAWADA DELHI LUCKNOW BHOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH BHUBANESWAR RANCHI DEHRADUN HYDERABAD *LATE CITY VOL. 3 ISSUE 193 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable www.dailypioneer.com New DNA vaccine for Covid-19 Raashi Khanna: Shooting abroad P DoT allocates spectrum P as India battled Covid P ’ effective in mice, hamsters 5 for 5G trials to telecom operators 8 was upsetting 12 In brief GST Council leaves tax rate on Delhi will begin AP reports 229 Black unlocking slowly from Monday, says Kejriwal Coronavirus vaccines unchanged n elhi will begin unlocking gradually fungus cases in 1 day PNS NEW DELHI from Monday, thanks to the efforts of the two crore people of The GST Council on Friday left D n the city which helped bring under PNS VIJAYAWADA taxes on Covid-19 vaccines and control the second wave, Chief medical supplies unchanged but Minister Arvind Kejriwal said. "In the The gross number of exempted duty on import of a med- past 24 hours, the positivity rate has Mucormycosis (Black fungus) cases icine used for treatment of black been around 1.5 per cent with only went up to 808 in Andhra Pradesh fungus. 1,100 new cases being reported. This on Friday with 229 cases being A group of ministers will delib- is the time to unlock lest people reported afresh in one day. erate on tax structure on the vac- escape corona only to die of hunger," “Lack of sufficient stock of med- cine and medical supplies, Finance Kejriwal said. -

SEPTEMBER 10, 1991 (Special Piovis/Dn$J Bill 358 (Sh

349 MattMB Under Rule 377 BHADRA 19, .1913 (SAKA) P/acss of WOIShjJ 350 (Special Provisions) 8171 industries, strengthen and widen the exist- Katni and Bina on a shorter and direct route ing flood banks to avert floods and thus save in public interest. the people of this area from recurring losses and release funds from coastal development The existing only train, namely, Ms- fund for the development of coastal area. hakoshal Express runs on a circuitious route thus taking several additional houes Incon- (viI) Need to fill up the vacancle. veniencing the commuters to reach their of managing Director and respective destinations. Moreover, once Chairman In the New Bank started as on Express Train, it has been of india urgently reduced to a passenger train stopping at various small stations and runs in variably SHRt MORESHWAR SAVE (Auran- late and is always packed beyond its capac- gabad): Sir, the New Bank of India a nation- ity alised ban~ has suffered a Joss of approxi- mately Rs. 10 crore in the financial year Thus, there is every justification for a 1989-90. It is learnt that the loss for the new train. I would, therefore, urge upon the financial year 1990-91. is even higher. Railway Minister to make a statement, re- garding introduction of much a train during One of the major reasons attributable the current session itself. to this is the vacant posts of the Chairman and Managing Director since long. For the last 1 112 years, one of the Executive Direc- tors is heading the bank. The Reserve Bank 13.16 hr. -

Multidimensional Role of Women in Shaping the Great Epic Ramayana

International Journal of Academic Research and Development International Journal of Academic Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4197 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.academicsjournal.com Volume 2; Issue 6; November 2017; Page No. 1035-1036 Multidimensional role of women in shaping the great epic Ramayana Punit Sharma Assistant Professor, Institute of Management & Research IMR Campus, NH6, Jalgaon, Maharashtra, India Abstract We look for role models all around, but the truth is that some of the greatest women that we know of come from Indian mythology Ramayana. It is filled with women who had the fortitude and determination to stand up against all odds ones who set a great example for generations to come. Ramayana is full of women, who were mentally way stronger than the glorified heroes of this great Indian epic. From Jhansi Ki Rani to Irom Sharmila, From Savitribai Fule to Sonia Gandhi and From Jijabai to Seeta, Indian women have always stood up for their rights and fought their battles despite restrictions and limitations. They are the shining beacons of hope and have displayed exemplary dedication in their respective fields. I have studied few characters of Ramayana who teaches us the importance of commitment, ethical values, principles of life, dedication & devotion in relationship and most importantly making us believe in women power. Keywords: ramayana, seeta, Indian mythological epic, manthara, kaikeyi, urmila, women power, philosophical life, mandodari, rama, ravana, shabari, surpanakha Introduction Scope for Further Research The great epic written by Valmiki is one epic, which has Definitely there is a vast scope over the study for modern day mentioned those things about women that make them great. -

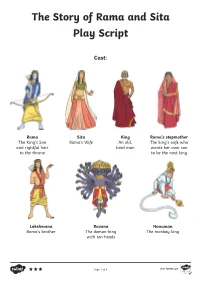

The Story of Rama and Sita Play Script

The Story of Rama and Sita Play Script Cast: Rama Sita King Rama’s stepmother The King’s Son Rama’s Wife An old, The king’s wife who and rightful heir tired man wants her own son to the throne to be the next king Lakshmana Ravana Hanuman Rama’s brother The demon-king The monkey king with ten heads Cast continued: Fawn Monkey Army Narrator 1 Monkey 1 Narrator 2 Monkey 2 Narrator 3 Monkey 3 Narrator 4 Monkey 4 Monkey 5 Prop Ideas: Character Masks Throne Cloak Gold Bracelets Walking Stick Bow and Arrow Diva Lamps (Health and Safety Note-candles should not be used) Audio Ideas: Bird Song Forest Animal Noises Lights up. The palace gardens. Rama and Sita enter the stage. They walk around, talking and laughing as the narrator speaks. Birds can be heard in the background. Once upon a time, there was a great warrior, Prince Rama, who had a beautiful Narrator 1: wife named Sita. Rama and Sita stop walking and stand in the middle of the stage. Sita: (looking up to the sky) What a beautiful day. Rama: (looking at Sita) Nothing compares to your beauty. Sita: (smiling) Come, let’s continue. Rama and Sita continue to walk around the stage, talking and laughing as the narrator continues. Rama was the eldest son of the king. He was a good man and popular with Narrator 1: the people of the land. He would become king one day, however his stepmother wanted her son to inherit the throne instead. Rama’s stepmother enters the stage. -

Rajesh Kumar Gupta Page 48 AMAR CHITRA KATHA: the FIGURE OF

International Journal of Movement Education and Social Science ISSN (Print): 2278-0793 IJMESS Vol. 7 Special Issue 1 (Jan-June 2018) www.ijmess.org ISSN (Online): 2321-3779 AMAR CHITRA KATHA: THE FIGURE OF RAM AND HINDU MASS MOBILIZATION relied heavily on the symbols of Ram and Ramyana Rajesh Kumar Gupta was Mahatma Gandhi. He brought the concept of Ram Rajya. For Gandhi, Ram Rajya was an ideal Abstract „republic‟ where values of justice, equality, idealism, In this paper I tried to explore how the popular renunciation and sacrifice are practiced. His idea of comics of Amar Chitra Katha based on Ram and Satyagraha was derived from Ramyana and Geeta. Ramyana the psychology of the comics reader in the The conceptual root of the application of the concept late influenced tweinteeth century. It also shows as of Ahimsa also lay in the Geeta and Ramyan in to how these comics laid the background of ugra which it was reared, to political action.2 Gandhi's Ram instead of benovelent Ram? This was the time imaginative invention and usage of symbols when, ugra Ram became the symbol of Hindu resonated in the minds and hearts of Indians.3 With Nationalism, he was utilised as a political figure the above examples of Baba Ramchandra and which was directly or indirectly linked with the Hindu- Mahatma Gandhi, I wish to emphasize that symbols Muslim conflicts, and it also sharpning the religious of Hindu epics and figure of Ram were utilized to identity for the construction of Ram temple in critique the colonial rule and the idea of Ram Rajya Ayodhya. -

Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava Sampradaya Connected to the Madhva Line?

Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava sampradaya connected to the Madhva line? Is the Gaudiya Vaishnava sampradaya connected to the Madhva line? – Jagadananda Das – The relationship of the Madhva-sampradaya to the Gaudiya Vaishnavas is one that has been sensitive for more than 200 years. Not only did it rear its head in the time of Baladeva Vidyabhushan, when the legitimacy of the Gaudiyas was challenged in Jaipur, but repeatedly since then. Bhaktivinoda Thakur wrote in his 1892 work Mahaprabhura siksha that those who reject this connection are “the greatest enemies of Sri Krishna Chaitanya’s family of followers.” In subsequent years, nearly every scholar of Bengal Vaishnavism has cast his doubts on this connection including S. K. De, Surendranath Dasgupta, Sundarananda Vidyavinoda, Friedhelm Hardy and others. The degree to which these various authors reject this connection is different. According to Gaudiya tradition, Madhavendra Puri appeared in the 14th century. He was a guru of the Brahma or Madhva-sampradaya, one of the four (Brahma, Sri, Rudra and Sanaka) legitimate Vaishnava lineages of the Kali Yuga. Madhavendra’s disciple Isvara Puri took Sri Krishna Chaitanya as his disciple. The followers of Sri Chaitanya are thus members of the Madhva line. The authoritative sources for this identification with the Madhva lineage are principally four: Kavi Karnapura’s Gaura-ganoddesa-dipika (1576), the writings of Gopala Guru Goswami from around the same time, Baladeva’s Prameya-ratnavali from the late 18th century, and anothe late 18th century work, Narahari’s -

Kaveri – 2019 Annual Day Script Bala Kanda: Rama

Kaveri – 2019 Annual Day Script Bala Kanda: Rama marries Sita by breaking the bow of Shiva Janaka: I welcome you all to Mithila! As you see in front of you, is the bow of Shiva. Whoever is able to break this bow of Shiva shall wed my daughter Sita. Prince 1: Bows to the crowd and tries to lift the bow and is unsuccessful Prince 2: Bows to the crowd and tries to lift the bow and is unsuccessful Rama 1: Bows, prays to the bow, lifts it, strings it and pulls the string back and bends and breaks it Janaka: By breaking Shiva’s bow, Rama has won the challenge and Sita will be married to Rama the prince of Ayodhya. Ayodhya Kanda: Narrator: Rama, Sita, Lakshmana, Shatrugna, Bharata are all married in Mithila and return to Ayodhya and lived happily for a number of years. Ayodhya rejoiced and flourished under King Dasaratha and the good natured sons of the King. King Dasaratha felt it was time to crown Rama as the future King of Ayodhya. Dasaratha: Rama my dear son, I have decided that you will now become the Yuvaraja of Ayodhya and I would like to advice you on how to rule the kingdom. Rama 2: I will do what you wish O father! Let me get your blessings and mother Kausalya’s blessings. (Rama bows to Dasaratha and goes to Kausalya) Kausalya: Rama, I bless you to rule this kingdom just like your father. Narrator: In the mean time, Manthara, Kaikeyi’s maid hatches out an evil plan. -

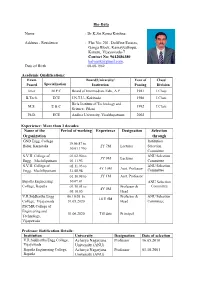

Dr.K.Sri Rama Krishna Address

Bio-Data Name : Dr.K.Sri Rama Krishna Address - Residence : Flat No: 201, Dolffine Estates, Ganga Block, Kamayyathopu, Kanuru, Vijayawada-7 Contact No: 9642086380 [email protected], Date of Birth : 08-08-1962 Academic Qualifications: Exam Board/University/ Year of Class/ Passed Specialization Institution Passing Division Inter M.P.C Board of Intermediate Edn., A.P. 1981 I Class B.Tech. ECE J.N.T.U., Kakinada 1986 I Class Birla Institute of.Technology and M.S. E & C 1992 I Class Science., Pilani Ph.D. ECE Andhra University, Visakhapatnam 2002 Experience: More than 3 decades Name of the Period of working Experience Designation Selection Organization through GND Engg. College Institution 19.06.87 to Bidar, Karnataka 2Y 7M Lecturer Selection 30.01.1990 Committee S.V.H. College of 01.02.90 to ANU Selection 3Y 9M Lecturer Engg. Machilipatnam 01.11.93 Committee S.V.H. College of 02.11.93 to ANU Selection 4Y 10M Asst. Professor Engg. Machilipatnam 31.08.98 Committee 01.10.98 to 3Y 1M Asst. Professor Bapatla Engineering 30.09.01 ANU Selection College, Bapatla 01.10.01 to Professor & Committee 4Y 0M 05.10.05 Head V.R.Siddhartha Engg 06.10.05 to Professor & ANU Selection 14 Y 8M College, Vijayawada 31.05.2020 Head Committee PSCMR College of Engineering and 01.06.2020 Till date Principal Technology, Vijayawada Professor Ratification Details: Institution University Designation Date of selection V.R.Siddhartha Engg College, Acharya Nagarjuna Professor 16.05.2010 Vijayawada University (ANU) Bapatla Engineering College, Acharya Nagarjuna Professor 01.10.2001