E-Ventures Worldwide V. Google

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

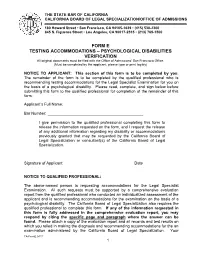

Form E – Testing Accommodations

THE STATE BAR OF CALIFORNIA CALIFORNIA BOARD OF LEGAL SPECIALIZATION/OFFICE OF ADMISSIONS 180 Howard Street • San Francisco, CA 94105-1639 • (415) 538-2300 845 S. Figueroa Street • Los Angeles, CA 90017-2515 • (213) 765-1500 FORM E TESTING ACCOMMODATIONS – PSYCHOLOGICAL DISABILITIES VERIFICATION All original documents must be filed with the Office of Admissions’ San Francisco Office. (Must be completed by the applicant; please type or print legibly) NOTICE TO APPLICANT: This section of this form is to be completed by you. The remainder of the form is to be completed by the qualified professional who is recommending testing accommodations for the Legal Specialist Examination for you on the basis of a psychological disability. Please read, complete, and sign below before submitting this form to the qualified professional for completion of the remainder of this form. Applicant’s Full Name: Bar Number: I give permission to the qualified professional completing this form to release the information requested on the form, and I request the release of any additional information regarding my disability or accommodations previously granted that may be requested by the California Board of Legal Specialization or consultant(s) of the California Board of Legal Specialization. Signature of Applicant Date NOTICE TO QUALIFIED PROFESSIONAL: The above-named person is requesting accommodations for the Legal Specialist Examination. All such requests must be supported by a comprehensive evaluation report from the qualified professional who conducted an individualized assessment of the applicant and is recommending accommodations for the examination on the basis of a psychological disability. The California Board of Legal Specialization also requires the qualified professional to complete this form. -

Minutes of Claremore Public Works Authority Meeting Council Chambers, City Hall, 104 S

MINUTES OF CLAREMORE PUBLIC WORKS AUTHORITY MEETING COUNCIL CHAMBERS, CITY HALL, 104 S. MUSKOGEE, CLAREMORE, OKLAHOMA MARCH 03, 2008 CALL TO ORDER Meeting called to order by Mayor Brant Shallenburger at 6:00 P.M. ROLL CALL Nan Pope called roll. The following were: Present: Brant Shallenburger, Buddy Robertson, Tony Mullenger, Flo Guthrie, Mick Webber, Terry Chase, Tom Lehman, Paula Watson Absent: Don Myers Staff Present: City Manager Troy Powell, Nan Pope, Serena Kauk, Matt Mueller, Randy Elliott, Cassie Sowers, Phil Stowell, Steve Lett, Daryl Golbek, Joe Kays, Gene Edwards, Tim Miller, Tamryn Cluck, Mark Dowler Pledge of Allegiance by all. Invocation by James Graham, Verdigris United Methodist Church. ACCEPTANCE OF AGENDA Motion by Mullenger, second by Lehman that the agenda for the regular CPWA meeting of March 03, 2008, be approved as written. 8 yes, Mullenger, Lehman, Robertson, Guthrie, Shallenburger, Webber, Chase, Watson. ITEMS UNFORESEEN AT THE TIME AGENDA WAS POSTED None CALL TO THE PUBLIC None CURRENT BUSINESS Motion by Mullenger, second by Lehman to approve the following consent items: (a) Minutes of Claremore Public Works Authority meeting on February 18, 2008, as printed. (b) All claims as printed. (c) Approve budget supplement for upgrading the electric distribution system and adding an additional Substation for the new Oklahoma Plaza Development - $586,985 - Leasehold improvements to new project number assignment. (Serena Kauk) (d) Approve budget supplement for purchase of an additional concrete control house for new Substation #5 for Oklahoma Plaza Development - $93,946 - Leasehold improvements to new project number assignment. (Serena Kauk) (e) Approve budget supplement for electrical engineering contract with Ledbetter, Corner and Associates for engineering design phase for Substation #5 - Oklahoma Plaza Development - $198,488 - Leasehold improvements to new project number assignment. -

Los Angeles Transportation Transit History – South LA

Los Angeles Transportation Transit History – South LA Matthew Barrett Metro Transportation Research Library, Archive & Public Records - metro.net/library Transportation Research Library & Archive • Originally the library of the Los • Transportation research library for Angeles Railway (1895-1945), employees, consultants, students, and intended to serve as both academics, other government public outreach and an agencies and the general public. employee resource. • Partner of the National • Repository of federally funded Transportation Library, member of transportation research starting Transportation Knowledge in 1971. Networks, and affiliate of the National Academies’ Transportation • Began computer cataloging into Research Board (TRB). OCLC’s World Catalog using Library of Congress Subject • Largest transit operator-owned Headings and honoring library, forth largest transportation interlibrary loan requests from library collection after U.C. outside institutions in 1978. Berkeley, Northwestern University and the U.S. DOT’s Volpe Center. • Archive of Los Angeles transit history from 1873-present. • Member of Getty/USC’s L.A. as Subject forum. Accessing the Library • Online: metro.net/library – Library Catalog librarycat.metro.net – Daily aggregated transportation news headlines: headlines.metroprimaryresources.info – Highlights of current and historical documents in our collection: metroprimaryresources.info – Photos: flickr.com/metrolibraryarchive – Film/Video: youtube/metrolibrarian – Social Media: facebook, twitter, tumblr, google+, -

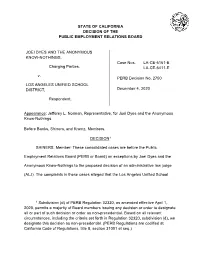

PERB Decision Number 2750-E

STATE OF CALIFORNIA DECISION OF THE PUBLIC EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS BOARD JOEI DYES AND THE ANONYMOUS KNOW-NOTHINGS, Case Nos. LA-CE-6161-E Charging Parties, LA-CE-6411-E v. PERB Decision No. 2750 LOS ANGELES UNIFIED SCHOOL DISTRICT, December 4, 2020 Respondent. Appearance: Jefferey L. Norman, Representative, for Joei Dyes and the Anonymous Know-Nothings. Before Banks, Shiners, and Krantz, Members. DECISION1 SHINERS, Member: These consolidated cases are before the Public Employment Relations Board (PERB or Board) on exceptions by Joei Dyes and the Anonymous Know-Nothings to the proposed decision of an administrative law judge (ALJ). The complaints in these cases alleged that the Los Angeles Unified School 1 Subdivision (d) of PERB Regulation 32320, as amended effective April 1, 2020, permits a majority of Board members issuing any decision or order to designate all or part of such decision or order as non-precedential. Based on all relevant circumstances, including the criteria set forth in Regulation 32320, subdivision (d), we designate this decision as non-precedential. (PERB Regulations are codified at California Code of Regulations, title 8, section 31001 et seq.) District violated the Educational Employment Relations Act (EERA)2 by taking numerous adverse actions against Dyes because she engaged in EERA-protected activities and taking other actions that interfered with her right to engage in such activities. The ALJ dismissed the complaints, finding that the District’s actions were not retaliatory and did not interfere with Dyes’ right to engage in protected activities. Based on our review of the proposed decision, the entire record, and relevant legal authority in light of Dyes’ exceptions, we conclude the ALJ’s factual findings are supported by the record,3 and the ALJ’s conclusions of law are well-reasoned and consistent with applicable law, with one exception. -

Miamidade.Gov/Transit 311 Or 305.468.5900 TTY/Fla Relay: 711

BURGER DIPLOMAT KING WALMART MALL Hallandale Beach Blvd HALLANDALE d e BEACH v ds e l 1 r n B (BROWARD CO.) h a S l T s U AVENTURA MALL I / GULFSTREAM E lvd d PARK B v vt . l / A B St 9 e 19 n LAKE y AVENTURA a EASTBOUND TRIPS CITI- c HOSPITAL s BANK i B oun C tr d t) y d Club v D s l R e r l ( i E B JC a . W GARAGE a ( g PENNEY 203 St c i s s b t i ) A B NE 199 St vc rd s NORDSTROM ice rd erv s THE BUS TERMINAL AT AVENTURA MALL WESTBOUND TRIPS Countr t) y Club s Dr e ( E W a ( s t 5 6 7 8 9 ) Board at Bay 7 193 St Lehman GOLDEN GLADES WEST ice rd Cswy rv PARK & RIDE se lk 0 b 7 A 00 6 v 1 e 78 1 r EAST D 178 St 170 St y BOUND a d JACKSON B 3 R e e 174 St NORTH HOSP. 5 v v A A 3 A e 4 A v v 2 5 168 St A 1 2 v 163 St / NE 167 St 163 ST e E E 26 Sunny Isles 165 St MALL N N e svc rd Blvd / Cswy v e A v 164 St e A 163 St 163 St v e ami v i A d M v WEST NORTH l 170 St e NW 2 BOUND llins A N MIAMI BEACH v o 3 A c. -

The Neighborly Substation the Neighborly Substation Electricity, Zoning, and Urban Design

MANHATTAN INSTITUTE CENTER FORTHE RETHINKING DEVELOPMENT NEIGHBORLY SUBstATION Hope Cohen 2008 er B ecem D THE NEIGHBORLY SUBstATION THE NEIGHBORLY SUBstATION Electricity, Zoning, and Urban Design Hope Cohen Deputy Director Center for Rethinking Development Manhattan Institute In 1879, the remarkable thing about Edison’s new lightbulb was that it didn’t burst into flames as soon as it was lit. That disposed of the first key problem of the electrical age: how to confine and tame electricity to the point where it could be usefully integrated into offices, homes, and every corner of daily life. Edison then designed and built six twenty-seven-ton, hundred-kilowatt “Jumbo” Engine-Driven Dynamos, deployed them in lower Manhattan, and the rest is history. “We will make electric light so cheap,” Edison promised, “that only the rich will be able to burn candles.” There was more taming to come first, however. An electrical fire caused by faulty wiring seriously FOREWORD damaged the library at one of Edison’s early installations—J. P. Morgan’s Madison Avenue brownstone. Fast-forward to the massive blackout of August 2003. Batteries and standby generators kicked in to keep trading alive on the New York Stock Exchange and the NASDAQ. But the Amex failed to open—it had backup generators for the trading-floor computers but depended on Consolidated Edison to cool them, so that they wouldn’t melt into puddles of silicon. Banks kept their ATM-control computers running at their central offices, but most of the ATMs themselves went dead. Cell-phone service deteriorated fast, because soaring call volumes quickly drained the cell- tower backup batteries. -

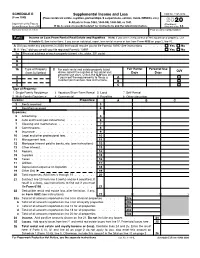

2020 Schedule E (Form 1040) 2020 Attachment Sequence No

SCHEDULE E Supplemental Income and Loss OMB No. 1545-0074 (Form 1040) (From rental real estate, royalties, partnerships, S corporations, estates, trusts, REMICs, etc.) ▶ Attach to Form 1040, 1040-SR, 1040-NR, or 1041. 2020 Department of the Treasury Attachment Internal Revenue Service (99) ▶ Go to www.irs.gov/ScheduleE for instructions and the latest information. Sequence No. 13 Name(s) shown on return Your social security number Part I Income or Loss From Rental Real Estate and Royalties Note: If you are in the business of renting personal property, use Schedule C. See instructions. If you are an individual, report farm rental income or loss from Form 4835 on page 2, line 40. A Did you make any payments in 2020 that would require you to file Form(s) 1099? See instructions . Yes No B If “Yes,” did you or will you file required Form(s) 1099? . Yes No 1a Physical address of each property (street, city, state, ZIP code) A B C 1b Type of Property 2 Fair Rental Personal Use For each rental real estate property listed QJV (from list below) above, report the number of fair rental and Days Days personal use days. Check the QJV box only A if you meet the requirements to file as a A B qualified joint venture. See instructions. B C C Type of Property: 1 Single Family Residence 3 Vacation/Short-Term Rental 5 Land 7 Self-Rental 2 Multi-Family Residence 4 Commercial 6 Royalties 8 Other (describe) Income: Properties: A B C 3 Rents received . 3 4 Royalties received . -

Why Use Google Sites? What Is an Eportfolio? Examples of G

Google Sites Creating Websites and e-Portfolios What is Google Sites? Google Sites is a free web application for creating websites. You can develop the website by yourself or collaborate with others to create the content of the pages. You can decide the level of sharing you would like to permit, who the owners of the website are, and to whom you’d like to give permission to edit or revise the site. You can also provide permission to visitors for viewing purposes only. Why Use Google Sites? ● It’s free and it’s easy to create. You don’t need to know any web coding. ● You can collaborate with other users or create the website solely. ● It is integrated with other Google Apps and tools so you can easily share video, photos, presentations, or calendars. ● Your site is stored on Google’s server. ● 100 MB of free online storage. ● Faculty and students can use Google Sites to create a professional ePortfolio. What is an ePortfolio? ● A collection of digital files (artifacts) that are shared electronically for the purpose of reflection, comment and evaluation. ● It’s quite simply a website that enables users to collate digital evidence of their learning. ● ePortfolios contain a wide range of digital files, including but not limited to, text or PDF documents, videos, sound files, images and links to other websites or online resources. Examples of Google Sites ePortfolios: ● Maxine Boggio’s Professional Teaching Portfolio ● The Veteran College Student’s Portfolio ● Kaitlin Craig’s ePortfolio Step 1: Getting Started 1) Go to sites.google.com 2) Enter your Montclair email address without mail, e.g. -

2017 Chevrolet Volt Hybrid-Electric Car Catalog Brochure

VOLT 2017 How you get there is important too. Take charge in the new Volt. Volt Premier in Siren Red Tintcoat (extra-cost color). Volt Premier in Kinetic Blue Metallic (extra-cost color). GOING GREEN HAS NEVER BEEN THIS REVOLUTIONARY. It’s not surprising that Green Car Journal picked the new Volt as the 2016 Green Car of the Year.® 1 Volt offers up to 53 pure electric miles2 on a single charge and up to 420 miles2 on a full charge and a full tank of gas. Chevrolet also expects owners will drive over 1,000 miles2 between fill-ups with regular charging. With impeccable style and advanced EV technologies like Regen on Demand™ and Location-Based Charging, going green doesn’t get any more revolutionary than this. 1 Visit GreenCarJournal.com for more information. 2 EPA-estimated 53-mile EV range based on 106 MPGe combined city/highway (electric); 367-mile extended range based on 42 MPG combined city/highway (gas). Actual range varies with conditions. EXTERIOR DESIGN Volt Premier in Kinetic Blue Metallic (extra-cost color). LOOKS CAN GO JUST AS FAR. That’s the EXPERIENCE EFFICIENCY. Aesthetically PRETTY SMART. You get the complete FILL-UPS? FEW AND FAR BETWEEN. beauty of it. The muscular new shape, and aerodynamically, it works together. package: a sporty look without sacrificing Chevrolet expects owners will drive over along with the upper and lower grille Deliberate contours and expressive intelligent features. Advanced EV 1,000 miles1 between fill-ups with regular pads, give Volt an identity of its own. proportions form a bold, confident stance technologies such as Regen on Demand, charging. -

Understanding How the Value Chains of E-Bus Public Transport Work for Six European Regions

Photo by Michael Dziedzic Marjoke de Boer University of Applied Science Utrecht Understanding how the value chains of e-bus public transport work for six European regions This project publication reflects the author’s views only and the Interreg Europe programme authorities are not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. Understanding how the value chains of e-bus public transport work for six European regions The Interreg Europe eBussed project supports the transition of Europe- an regions towards low carbon mobility and more efficient transport. The regions involved are Turku (Finland), Hamburg (Germany), Utrecht (The Netherlands), Livorno (Italy), South Transdanubia (Hungary) and Gozo island in Malta. It promotes the uptake of e-busses in new regions and supports the expansion of existing e-fleets. Within the project, there are four thematic working groups formed that aim at delivering a best practices report and policy recommendations to be used in the partner regions. Thematic Working Group 4 (TWG4) focusses on the topics of Procurement, Tendering and Costs of e-busses. As a starting point for TWG4, the value chain for e-bus public transport per region has been mapped. By mapping how the value chain for e-bus public transport works and defining the nature of the issues, problems or maybe challenges per region can be better understood. Concepts Value chain; Michael Porter describes a value chain as: “A collection of activities that an organization carries out to create value for its customers. Value creation gener- ates added value, which leads to competitive advantage. -

2015 Urban Water Management Plan California Water Service City of Hawthorne District

California Water Service 2015 Urban Water Management Plan City of Hawthorne District June 2016 Quality. Service. Value 2015 Urban Water Management Plan California Water Service City of Hawthorne District Table of Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................................... 5 List of Figures .................................................................................................................................. 8 List of Acronyms .............................................................................................................................. 9 Chapter 1 Introduction and Overview .......................................................................................... 11 1.1 Background and Purpose ............................................................................................... 11 1.2 Urban Water Management Planning and the California Water Code ........................... 12 1.3 Relation to Other Planning Efforts ................................................................................. 13 1.4 Plan Organization ........................................................................................................... 13 Chapter 2 Plan Preparation ........................................................................................................... 15 2.1 Basis for Preparing a Plan ............................................................................................... 15 2.2 Regional Planning -

Railway Electrification and Railway Productivity: a Study Report

Transportation Research Record 1029 23 Railway Electrification and Railway Productivity: A Study Report S. R. DITMEYER, J. R. MARTIN, P. E. OLSON, M. F. RISTER, B. A. ROSS, J. J. SCHMIDT, and E. H. SJOKVIST ABSTRACT various aspects of railroad productivity that might be influenced by the adop tion of electrified railroad operation are evaluated. Productivity is considered from the viewpoint of motive power, transportation economics, signaling and train control, and railway operations. The results of a productivity study undertaken by a diesel operation solely because of electrification, subcommittee of the TRB Committee on Rail Electrifi and then construct hypothetical models of known cation systems are presented. This seven-member railroad operations in North America, incorporating group evaluated various aspects of railroad produc the operating concepts gathered from this overseas tivity that might be influenced by the adoption of study. At best, the result is a mental simulation of electrified operation. Primary emphasis has been a railroad operation to which untested principles placed on productivity improvements that might be are applied and for which no opportunity exists to anticipated with electrification of heavy-density validate any part of the so-called model. When the main-line freight railroad operations. model results are evaluated, it is necessary to dis Each member of the subcommittee has been involved tinguish carefully between true effects of electri in one or more North American main-line railroad fication and consequential effects that are brought electrification studies in the United States or about primarily because a new, unconstrained look is Canada. In addition, each member of the subcommittee taken at the railroad operations.