Spatial Patterns of Endemism in Shallow-Water Reef Fish Populations of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epinephelus Coioides) from Northern Oman

490 NOAA First U.S. Commissioner National Marine Fishery Bulletin established 1881 of Fisheries and founder Fisheries Service of Fishery Bulletin Abstract—Age, growth, and monthly reproductive characteristics were Demographic profile of an overexploited determined for the orange-spotted serranid, the orange-spotted grouper grouper (Epinephelus coioides) from northern Oman. This species is char- (Epinephelus coioides), from northern Oman acterized by a prevalence of females (1–11 years old), and males make up 1,2 6.5% of the total sample. Growth pa- Jennifer L. McIlwain rameters indicate a typical pattern Aisha Ambu-ali1 for groupers with a low growth co- Nasr Al Jardani1 efficient (K=0.135). The trajectory of 3 the von Bertalanffy growth function Andrew. R. Halford was almost linear with no evidence Hamed S. Al-Oufi4 of asymptotic growth. Estimates of David A. Feary (contact author)5 mortality revealed a low natural mortality of 0.14/year but a high Email address for contact author: [email protected] fishing mortality of 0.59/year. More alarming was the high rate of exploi- 1 Department of Marine Science and Fisheries 4 tation (0.81/year), considered unsus- Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries College of Agricultural and Marine Sciences tainable for a slow-growing grouper. P.O. Box 1700, Muscat 111 Sultan Qaboos University The population off southern Oman Sultanate of Oman P.O. Box 34, Al-Khod 123 is diandric protogynous, and sex 5 School of Life Sciences Sultanate of Oman change takes place between 449 and University of Nottingham 748 mm in total length (TL) or over 2 Department of Environment and Agriculture University Park a period of 4–8 years. -

Use of Productivity and Susceptibility Indices to Determine the Vulnerability of a Stock: with Example Applications to Six U.S

Use of productivity and susceptibility indices to determine the vulnerability of a stock: with example applications to six U.S. fisheries. Wesley S. Patrick1, Paul Spencer2, Olav Ormseth2, Jason Cope3, John Field4, Donald Kobayashi5, Todd Gedamke6, Enric Cortés7, Keith Bigelow5, William Overholtz8, Jason Link8, and Peter Lawson9. 1NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Office of Sustainable Fisheries, 1315 East- West Highway, Silver Spring, MD 20910; 2 NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, 7600 Sand Point Way, Seattle, WA 98115; 3NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Northwest Fisheries Science Center, 2725 Montlake Boulevard East, Seattle, WA 98112; 4NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, 110 Shaffer Road, Santa Cruz, CA 95060; 5NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, 2570 Dole Street, Honolulu, HI 96822; 6NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Southeast Fisheries Science Center, 75 Virginia Beach Drive, Miami, FL 33149; 7NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Southeast Fisheries Science Center, 3500 Delwood Beach Road, Panama City, FL 32408; 8NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Northeast Fisheries Science Center, 166 Water Street, Woods Hole, MA 02543; 9NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Northwest Fisheries Science Center, 2030 South Marine Science Drive, Newport, OR 97365. CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Wesley S. Patrick, NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service, Office of Sustainable Fisheries, 1315 East-West -

Genetic Analyses and Simulations of Larval Dispersal Reveal Distinct

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Journal of Marine Biology Volume 2011, Article ID 765353, 11 pages doi:10.1155/2011/765353 Research Article Genetic Analyses and Simulations of Larval Dispersal Reveal Distinct Populations and Directional Connectivity across the Range of the Hawaiian Grouper (Epinephelus quernus) Malia Ana J. Rivera,1 Kimberly R. Andrews,1 Donald R. Kobayashi,2 Johanna L. K. Wren,1, 3 Christopher Kelley,4 George K. Roderick,5 and Robert J. Toonen1 1 Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa,¯ P.O. Box 1346, Kane‘ohe,¯ HI 96744, USA 2 Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2570 Dole Street, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 3 Department of Oceanography, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa,¯ 1000 Pope Road, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 4 Hawai‘i Undersea Research Laboratory, University of Hawai‘i at Manoa,¯ 1000 Pope Road, MSB 303, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 5 Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management, University of California, 130 Mulford Hall, MC 3114, Berkeley, CA 94708-3114, USA CorrespondenceshouldbeaddressedtoM.A.J.Rivera,[email protected] Received 16 July 2010; Accepted 27 September 2010 Academic Editor: Benjamin S. Halpern Copyright © 2011 Malia Ana J. Rivera et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Integration of ecological and genetic data to study patterns of biological connectivity can aid in ecosystem-based management. Here we investigated connectivity of the Hawaiian grouper Epinephelus quernus, a species of management concern within the Main Hawaiian Islands (MHI), by comparing genetic analyses with simulated larval dispersal patterns across the species range in the Hawaiian Archipelago and Johnston Atoll. -

Deep Bottom ID

by par Lindsay Chapman, Aymeric Desurmont, Youngmi Choi, Lindsay Chapman, Aymeric Desurmont, Youngmi Choi, Pierre Boblin, William Sokimi and Steve Beverly Pierre Boblin, William Sokimi et Steve Beverly nzaid ii © Copyright Secretariat of the Pacific Community 2008 © Copyright Secrétariat général de la Communauté du Pacifique 2008 All rights for commercial / for profit reproduction or translation, in any Tous droits réservés de reproduction ou de traduction à des fins commer- form, reserved. SPC authorises the partial reproduction or translation of ciales/lucratives, sous quelque forme que ce soit. Le Secrétariat général de this material for scientific, educational or research purposes, provided SPC la Communauté du Pacifique autorise la reproduction ou la traduction par- and the source document are properly acknowledged. Permission to tielles de ce document à des fins scientifiques ou éducatives ou pour les reproduce the document and/or translate in whole, in any form, whether besoins de la recherche, à condition qu’il soit fait mention de la CPS et de for commercial / for profit or non-profit purposes, must be requested in la source. L’autorisation de la reproduction et/ou de la traduction intégrale writing. Original SPC artwork may not be altered or separately published ou partielle de ce document, sous quelque forme que ce soit, à des fins without permission. commerciales/lucratives ou à titre gratuit, doit être sollicitée au préalable par écrit. Il est interdit de modifier ou de publier séparément des Original text: English and French graphismes originaux de la CPS sans autorisation préalable. Texte original :anglais et français Secretariat of the Pacific Community Cataloguing-in-publication data Chapman, L. -

Epinephelus Marginatus and E. Morio

Begossi et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2019) 15:53 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-019-0331-2 RESEARCH Open Access Fishers and groupers (Epinephelus marginatus and E. morio) in the coast of Brazil: integrating information for conservation Alpina Begossi1,2,3* , Svetlana Salyvonchyk1,4, Branko Glamuzina1,5, Shirley Pacheco de Souza1,6, Priscila F. M. Lopes1,7, Regina H. G. Priolli1,2,3, Djalma Osmanir do Prado3, Milena Ramires1,3, Mariana Clauzet1,8, Cleverson Zapelini9, Daiana T. Schneider10, Luis T. Silva10 and Renato A. M. Silvano1,10 Abstract Background: Groupers are a vulnerable but economically important group of fish, especially for small-scale fisheries. We investigated catches and local ecological knowledge (LEK) of diet, habitat, and past fishing experiences. Methods: Landings, prices, interviews, and restaurants demand for two species, Epinephelus marginatus (dusky grouper) and Epinephelus morio (red grouper), were registered. Results: We visited 74 markets and 79 sites on the coast of Brazil in 2017–2018, and we interviewed 71 fishers: Bahia (NE), Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo (SE), and Santa Catarina (S). The landings sampled of dusky grouper (2016–2017) in Rio de Janeiro were: n = 222, size 38–109 cm, weight 1–24 kg, average 3.84 kg; in São Paulo, São Sebastião were: n =47, size 39–106 cm, weight 2–8 kg, average of 2.77 kg; and at Santos: n =80,26–120 cm, weight 0.36–15 kg, average 2.72 kg. Red grouper was observed in markets in the northeastern Brazil. We did not observe Epinephelus marginatus from Bahia northward; a maximum size of 200 cm was reported south of the Bahia, besides Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo coasts, 20 years ago (or longer) by 12 fishers. -

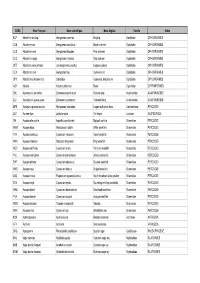

ASFIS ISSCAAP Fish List February 2007 Sorted on Scientific Name

ASFIS ISSCAAP Fish List Sorted on Scientific Name February 2007 Scientific name English Name French name Spanish Name Code Abalistes stellaris (Bloch & Schneider 1801) Starry triggerfish AJS Abbottina rivularis (Basilewsky 1855) Chinese false gudgeon ABB Ablabys binotatus (Peters 1855) Redskinfish ABW Ablennes hians (Valenciennes 1846) Flat needlefish Orphie plate Agujón sable BAF Aborichthys elongatus Hora 1921 ABE Abralia andamanika Goodrich 1898 BLK Abralia veranyi (Rüppell 1844) Verany's enope squid Encornet de Verany Enoploluria de Verany BLJ Abraliopsis pfefferi (Verany 1837) Pfeffer's enope squid Encornet de Pfeffer Enoploluria de Pfeffer BJF Abramis brama (Linnaeus 1758) Freshwater bream Brème d'eau douce Brema común FBM Abramis spp Freshwater breams nei Brèmes d'eau douce nca Bremas nep FBR Abramites eques (Steindachner 1878) ABQ Abudefduf luridus (Cuvier 1830) Canary damsel AUU Abudefduf saxatilis (Linnaeus 1758) Sergeant-major ABU Abyssobrotula galatheae Nielsen 1977 OAG Abyssocottus elochini Taliev 1955 AEZ Abythites lepidogenys (Smith & Radcliffe 1913) AHD Acanella spp Branched bamboo coral KQL Acanthacaris caeca (A. Milne Edwards 1881) Atlantic deep-sea lobster Langoustine arganelle Cigala de fondo NTK Acanthacaris tenuimana Bate 1888 Prickly deep-sea lobster Langoustine spinuleuse Cigala raspa NHI Acanthalburnus microlepis (De Filippi 1861) Blackbrow bleak AHL Acanthaphritis barbata (Okamura & Kishida 1963) NHT Acantharchus pomotis (Baird 1855) Mud sunfish AKP Acanthaxius caespitosa (Squires 1979) Deepwater mud lobster Langouste -

Reef Fish Dispersal in the Hawaiian Archipelago: Comparative Phylogeography of Three Endemic Damselfishes

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Journal of Marine Biology Volume 2016, Article ID 3251814, 17 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2016/3251814 Research Article Reef Fish Dispersal in the Hawaiian Archipelago: Comparative Phylogeography of Three Endemic Damselfishes Kimberly A. Tenggardjaja,1 Brian W. Bowen,2 and Giacomo Bernardi1 1 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California Santa Cruz, 100 Shaffer Road, SantaCruz,CA95060,USA 2Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology, University of Hawaii, P.O. Box 1346, Kaneohe, HI 96744, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Kimberly A. Tenggardjaja; [email protected] Received 2 November 2015; Accepted 8 March 2016 Academic Editor: Yehuda Benayahu Copyright © 2016 Kimberly A. Tenggardjaja et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Endemic marine species at remote oceanic islands provide opportunities to investigate the proposed correlation between range size and dispersal ability. Because these species have restricted geographic ranges, it is assumed that they have limited dispersal ability, which consequently would be reflected in high population genetic structure. To assess this relationship at a small scale and to determine if it may be related to specific reef fish families, here we employ a phylogeographic survey of three endemic Hawaiian damselfishes: Abudefduf abdominalis, Chromis ovalis,andChromis verater. Data from mitochondrial markers cytochrome b and control region revealed low but significant genetic structure in all three species. Combining these results with data froma previous study on Dascyllus albisella and Stegastes marginatus, all five endemic damselfish species surveyed to date show evidence of genetic structure, in contrast with other widespread reef fish species that lack structure within the Hawaiian Archipelago. -

Nom Français

CODE Nom Français Nom scientifique Nom Anglais Famille Ordre KCP Abadèche du Cap Genypterus capensis Kingklip Ophidiidae OPHIDIIFORMES CUB Abadèche noir Genypterus maculatus Black cusk-eel Ophidiidae OPHIDIIFORMES CUS Abadèche rosé Genypterus blacodes Pink cusk-eel Ophidiidae OPHIDIIFORMES CUC Abadèche rouge Genypterus chilensis Red cusk-eel Ophidiidae OPHIDIIFORMES OFZ Abadèche sans jambes Lamprogrammus exutus Legless cuskeel Ophidiidae OPHIDIIFORMES CEX Abadèches nca Genypterus spp Cusk-eels nei Ophidiidae OPHIDIIFORMES OPH Abadèches, brotules nca Ophidiidae Cusk-eels, brotulas nei Ophidiidae OPHIDIIFORMES ALR Ablette Alburnus alburnus Bleak Cyprinidae CYPRINIFORMES ZML Acanthure à pierreries Zebrasoma gemmatum Spotted tang Acanthuridae ACANTHUROIDEI ZLV Acanthure à queue jaune Zebrasoma xanthurum Yellowtail tang Acanthuridae ACANTHUROIDEI MPS Achigan à grande bouche Micropterus salmoides Largemouth black bass Centrarchidae PERCOIDEI LQT Acmée râpe Lottia limatula File limpet Lottiidae GASTROPODA ISA Acoupa aile-courte Isopisthus parvipinnis Bigtooth corvina Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI WEW Acoupa blanc Atractoscion nobilis White weakfish Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI YNV Acoupa cambucu Cynoscion virescens Green weakfish Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI WKK Acoupa chasseur Macrodon ancylodon King weakfish Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI WEP Acoupa du Pérou Cynoscion analis Peruvian weakfish Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI YNJ Acoupa mongolare Cynoscion jamaicensis Jamaica weakfish Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI SWF Acoupa pintade Cynoscion nebulosus Spotted weakfish Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI WKS Acoupa -

![Serranus Polystigma Bleeker, 1853A:244 (Type Localities: “Benculen, Sumatra” [= ?Bengkulu, Sumatera] and Ambon, Indonesia)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5818/serranus-polystigma-bleeker-1853a-244-type-localities-benculen-sumatra-bengkulu-sumatera-and-ambon-indonesia-3375818.webp)

Serranus Polystigma Bleeker, 1853A:244 (Type Localities: “Benculen, Sumatra” [= ?Bengkulu, Sumatera] and Ambon, Indonesia)

click for previous page 216 FAO Species Catalogue Vol. 16 Epinephelus polystigma (Bleeker, 1853) Fig. 387; PI. XXIA SERRAN Epin 89 Serranus polystigma Bleeker, 1853a:244 (type localities: “Benculen, Sumatra” [= ?Bengkulu, Sumatera] and Ambon, Indonesia). Synonyms: Serranus australis Castelnau, 1875:7 (type locality: Cape York, Queensland, Australia). Epinephelus rahanus Popta, 1918:1 (type locality: Raha, Muna, Sulawesi [Celebes], Indonesia). FAO Names: En - White-dotted grouper; Fr - Mérou points blancs; Sp - Mero punteado blanco. Fig. 387 Epinephelus polystigma (256 mm standard length) Diagnostic Features:Body depth contained 2.6 to 2.9 times in standard length (for fish 10 to 38 cm standard length). Head length contained 2.3 to 2.7 times in standard length; interorbital area flat; snout short, its length subequal to eye diameter; preorbital depth less than greatest width of upper lip; preopercle rounded, finely serrate, the serrae at corner slightly enlarged; upper edge of operculum mostly straight; anterior nostrils funnel shaped, the rear margin expanded as a flap reaching rear nostril; rear nostril diameter 2 to 4 times larger than front nostril diameter; maxilla reaches past vertical at rear edge of eye, the lower edge with a rounded step at front of widest part; midlateral part of lower jaw with 2 or 3 rows of small subequal teeth; 2 short stout canines at front of both jaws. Gill rakers shorter than gill filaments, 8 or 9 on upper limb, 13 to 16 on lower limb, total 21 to 24. Dorsal fin with XI spines and 15 or 16 rays, the third or fourth spine longest, its length contained 2.7 to 3.3 times in head length and distinctly shorter than longest dorsal-fin rays, the interspinous membranes distinctly incised; anal fin with III spines and 8 rays; pectoral-fin rays 16 to 18; pectoral-fin length contained 1.6 to 1.8 times, pelvic-fin length contained 2.0 to 2.2 times in head length; caudal fin well rounded. -

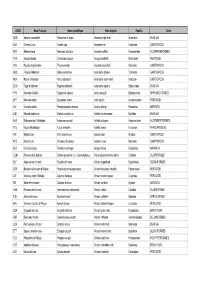

Liste Espèces

CODE Nom Français Nom scientifique Nom Anglais Famille Ordre ODQ Anomie cascabelle Pododesmus cepio Abalone jingle shell Anomiidae BIVALVIA ABX Ormeaux nca Haliotis spp Abalones nei Haliotidae GASTROPODA REN Sébaste rose Sebastes fasciatus Acadian redfish Scorpaenidae SCORPAENIFORMES YNA Acoupa toeroe Cynoscion acoupa Acoupa weakfish Sciaenidae PERCOIDEI HSV Pourpre aiguillonnee Thais aculeata Aculeate rock shell Muricidae GASTROPODA GBQ Troque d'Adanson Gibbula adansoni Adanson's gibbula Trochidae GASTROPODA NKA Natice d'Adanson Natica adansoni Adanson's moon snail Naticidae GASTROPODA GLW Tagal d'Adanson Tagelus adansonii Adanson's tagelus Solecurtidae BIVALVIA PYD Manchot d'Adélie Pygoscelis adeliae Adelie penguin Spheniscidae SPHENISCIFORMES QFT Maconde aden Synagrops adeni Aden splitfin Acropomatidae PERCOIDEI NIV Crevette adonis Parapenaeopsis venusta Adonis shrimp Penaeidae NATANTIA DJD Modiole adriatique Modiolus adriaticus Adriatic horse mussel Mytilidae BIVALVIA AAA Esturgeon de l'Adriatique Acipenser naccarii Adriatic sturgeon Acipenseridae ACIPENSERIFORMES FCV Fucus d'Adriatique Fucus virsoides Adriatic wrack Fucaceae PHAEOPHYCEAE IRR Mitre brûlée Mitra eremitarum Adusta miter Mitridae GASTROPODA KCE Murex bruni Chicoreus brunneus Adusta murex Muricidae GASTROPODA AES Crevette ésope Pandalus montagui Aesop shrimp Pandalidae NATANTIA CGM Poisson-chat, hybride Clarias gariepinus x C. macrocephalus Africa-bighead catfish, hybrid Clariidae SILURIFORMES SUF Ange de mer africain Squatina africana African angelshark Squatinidae SQUALIFORMES -

Genetic Structure Among Spawning Aggregations of the Gulf Coney Hyporthodus Acanthistius

Vol. 499: 193–201, 2014 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published March 3 doi: 10.3354/meps10637 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Genetic structure among spawning aggregations of the gulf coney Hyporthodus acanthistius Ricardo Beldade1,2,3,4,*, Alexis M. Jackson1, Richard Cudney-Bueno5,6, Peter T. Raimondi1, Giacomo Bernardi1 1Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California Santa Cruz, 100 Shaffer Road, Santa Cruz, California 95060, USA 2USR 3278 CRIOBE, CNRS EPHE, CBETM de l’Université de Perpignan, 66860 Perpignan Cedex, France 3Laboratoire d’excellence ‘Corail’, USR 3278 CRIOBE CNRS-EPHE, 66860 Perpignan Cedex, France 4Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Ciências, Centro de Oceanografia, Campo Grande, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal 5School of Natural Resources and the Environment, University of Arizona, Biological Sciences East, Room 325, Tucson, Arizona 85721, USA 6Institute of Marine Sciences, University of California Santa Cruz, 100 Shaffer Road, Santa Cruz, California 95060, USA ABSTRACT: Many large groupers form spawning aggregations, returning to the same spawning sites in consecutive spawning seasons. Connectivity between spawning aggregations is thus assured by larval dispersal. This study looks into the genetic structure and gene flow among spawning aggregations of a large grouper, the gulf coney Hyporthodus acanthistius, in the north- ern Gulf of California. First, using the mitochondrial control region and 11 microsatellites, we cal- culated FST metrics and conducted a Bayesian clustering analysis to determine structure among 5 spawning aggregations. Shallow genetic structure was found, separating the southernmost spawning aggregate from the remainder. Second, we used the results from the structure analysis and local water circulation patterns to delineate 3 distinct models of gene flow. -

Epinephelus Marginatus and E

Begossi et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine (2019) 15:53 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-019-0331-2 RESEARCH Open Access Fishers and groupers (Epinephelus marginatus and E. morio) in the coast of Brazil: integrating information for conservation Alpina Begossi1,2,3* , Svetlana Salyvonchyk1,4, Branko Glamuzina1,5, Shirley Pacheco de Souza1,6, Priscila F. M. Lopes1,7, Regina H. G. Priolli1,2,3, Djalma Osmanir do Prado3, Milena Ramires1,3, Mariana Clauzet1,8, Cleverson Zapelini9, Daiana T. Schneider10, Luis T. Silva10 and Renato A. M. Silvano1,10 Abstract Background: Groupers are a vulnerable but economically important group of fish, especially for small-scale fisheries. We investigated catches and local ecological knowledge (LEK) of diet, habitat, and past fishing experiences. Methods: Landings, prices, interviews, and restaurants demand for two species, Epinephelus marginatus (dusky grouper) and Epinephelus morio (red grouper), were registered. Results: We visited 74 markets and 79 sites on the coast of Brazil in 2017–2018, and we interviewed 71 fishers: Bahia (NE), Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo (SE), and Santa Catarina (S). The landings sampled of dusky grouper (2016–2017) in Rio de Janeiro were: n = 222, size 38–109 cm, weight 1–24 kg, average 3.84 kg; in São Paulo, São Sebastião were: n = 47, size 39–106 cm, weight 2–8 kg, average of 2.77 kg; and at Santos: n = 80, 26–120 cm, weight 0.36–15 kg, average 2.72 kg. Red grouper was observed in markets in the northeastern Brazil. We did not observe Epinephelus marginatus from Bahia northward; a maximum size of 200 cm was reported south of the Bahia, besides Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo coasts, 20 years ago (or longer) by 12 fishers.