Symbolism of the Cross in Sacred Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Drama of Humanity and Other Miscellaneous Papers 1939-1985

the collected works of ERIC VOEGELIN VOLUME 33 THE DRAMA OF HUMANITY AND OTHER MISCELLANEOUS PAPERS, 1939–1985 This page intentionally left blank projected volumes in the collected works 1. On the Form of the American Mind 2. Race and State 3. The History of the Race Idea: From Ray to Carus 4. The Authoritarian State: An Essay on the Problem of the Austrian State 5. Modernity without Restraint: The Political Religions; The New Science of Politics; and Science, Politics, and Gnosticism 6. Anamnesis: On the Theory of History and Politics 7. Published Essays, 1922–1928 8. Published Essays, 1928–1933 9. Published Essays, 1934–1939 10. Published Essays, 1940–1952 11. Published Essays, 1953–1965 12. Published Essays, 1966–1985 13. Selected Book Reviews 14. Order and History, Volume I, Israel and Revelation 15. Order and History, Volume II, The World of the Polis 16. Order and History, Volume III, Plato and Aristotle 17. Order and History, Volume IV, The Ecumenic Age 18. Order and History, Volume V, In Search of Order 19. History of Political Ideas, Volume I, Hellenism, Rome, and Early Christianity 20. History of Political Ideas, Volume II, The Middle Ages to Aquinas 21. History of Political Ideas, Volume III, The Later Middle Ages 22. History of Political Ideas, Volume IV, Renaissance and Reformation 23. History of Political Ideas, Volume V, Religion and the Rise of Modernity 24. History of Political Ideas, Volume VI, Revolution and the New Science 25. History of Political Ideas, Volume VII, The New Order and Last Orientation 26. History of Political Ideas, Volume VIII, Crisis and the Apocalypse of Man 27. -

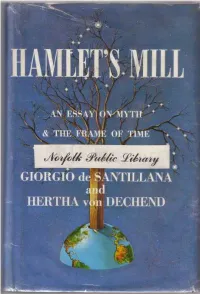

HAMLET's MILL.Pdf

Hamlet's Mill An essay on myth and the frame of time GIORGIO de SANTILLANA Professor of the History and Philosophy of Science M.l.T. and HERTHA von DECHEND apl. Professor fur Geschichte der Naturivissenschaften ]. W. Goethe-Universitat Frankfurt Preface ASthe senior, if least deserving, of the authors, I shall open the narrative. Over many years I have searched for the point where myth and science join. It was clear to me for a long time that the origins of science had their deep roots in a particular myth, that of invariance. The Greeks, as early as the 7th century B.C., spoke of the quest of their first sages as the Problem of the One and the Many, sometimes describing the wild fecundity of nature as the way in which the Many could be deduced from the One, sometimes seeing the Many as unsubstantial variations being played on the One. The oracular sayings of Heraclitus the Obscure do nothing but illustrate with shimmering paradoxes the illusory quality of "things" in flux as they were wrung from the central intuition of unity. Before him Anaximander had announced, also oracularly, that the cause of things being born and perishing is their mutual injustice to each other in the order of time, "as is meet," he said, for they are bound to atone forever for their mutual injustice. This was enough to make of Anaximander the acknowledged father of physical science, for the accent is on the real "Many." But it was true science after a fashion. Soon after, Pythagoras taught, no less oracularly, that "things are numbers." Thus mathematics was born. -

4 Days / 3 Nights Siem Reap Angkor Wat & Battambang Experience

4 Days / 3 Nights Siem Reap Angkor Wat & Battambang Experience Product Code : TREP4D(4ERM)-310320 Package include : * 03 night’s accommodation * Full board meals – 03 breakfasts, 02 lunches & 02 dinner * Return airport-hotel-airport transfer * Full-day Angkor Heritage Tour * Full-day Excursion to North Battambang * English-speaking guide Sample itinerary : Day 01 _______ / SIEM REAP (No meal) Upon your arrival at Siem Reap International Airport, you will be met by our local representative and thereafter, transfer to your selected hotel for check-in. Rest of the day is free at leisure for you to explore the city. Day 02 SIEM REAP (Breakfast, Lunch, Dinner) After breakfast, begin the day with a visit to The South Gate of Angkor Thom, the last capital of the Khmer Empire. Explore the temples inside the walls of the “Great City” such as Bayon, Phimeanakas, Baphoun, Terrace of the Elephants as well as the Terrace of the Leper King; followed by a small circuit tour of Thommanon, Chau Say Tevoda, Ta Keo and Ta Prohm, a temple with jungle-like atmosphere with a combination of giant trees and extensive roots growing out of the ruins. After lunch, explore the grounds of Angkor Wat, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and one of the “Seven Wonders of the World”. Constructed during the first half of the 12th century and encompassing an area of about 400 acres, this awe-inspiring temple is the largest and the best-preserved monument within the ancient city that was the epicentre of the Khmer empire that once ruled most of Southeast Asia. -

A Statue of Aphrodite in the Royal Ontario Museum

The Art Bulletin ISSN: 0004-3079 (Print) 1559-6478 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rcab20 A Statue of Aphrodite in the Royal Ontario Museum Cornelia G. Harcum To cite this article: Cornelia G. Harcum (1921) A Statue of Aphrodite in the Royal Ontario Museum, The Art Bulletin, 4:2, 45-58, DOI: 10.1080/00043079.1921.11409714 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00043079.1921.11409714 Published online: 22 Dec 2015. Submit your article to this journal View related articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rcab20 Download by: [Nanyang Technological University] Date: 09 May 2016, At: 01:43 Downloaded by [Nanyang Technological University] at 01:43 09 May 2016 '\'O HO S T O , \{ O YAI .OS T AH( O :'II u. ·n:u ~ ( 0'" ,\ 11 ( '11,1-:0 1.0 <:\': r .: s us TIn: :'\IOTIIEII A Statue of Aphrodite in the Royal On tario Museum By CORNELIA G. HARCUM IN 1909 the Royal Ontario Museum of Archreology acquired a Parian marble statue, which came originally from the mainland of Greece, and with its basis is just six feet high. It was presented to the museum by Sigmund Samuel, Esq. The woman, or goddess (PI. IX), stands majestically with weight resting on her right foot, her right hip projecting, her left knee bent and slightly advanced. She looks in the direction of the free foot. The position gives the impression of perfect repose yet of the possibility of perfect freedom and ease of motion. -

Trip Planner 6D5N Siem Reap – Battambang

PMT Address: 51, 7 Makara Road, Wat B SRG HOLIDAYS CAMBODIA Hotline : (855) 10 435331 l (855) 11 435331 l (855) 12 435331 Email : [email protected] | [email protected] Address : 20 Anson Place, Sala Konseng, Sangkat Svay Dangkum, Siem Reap, 17000 Cambodia. EXCLUSIVE TOUR – SRG HOLIDAYS CAMBODIA TOUR NAME : 6D5N SIEM REAP-ANGKOR TOUR CODE : SGREP1707P6 TRAVEL FROM : SEP 2017 to 31 March 2018 PROPOSED TOUR : Day Date Itinerary Meal Day 1 Arrival Siem Reap – Tonle Sap D Day 2 Angkor Archaelogical Park – Royal Enclosure B,L Day 3 Kulen Mountain National Park B,L Day 4 Siem Reap - Battambang B,,D Day 5 Battambang - Siem Reap B Day 6 Departure Siem Reap B Number of Guests / Price per person (in USD) 2 3 - 6 7 - 10 11 - 15 15 - 18 19+ SGL - Sup (1 FOC) 689 579 429 399 369 339 70 Category Accommodation Siem Reap Evergreen Hotel www.siemreapevergreenhotel.com Dinata Angkor Boutique Hotel www.dinataangkor.com Siem Reap Ladear Angkor Boutique Hotel www.ladearangkorhotel.com Udaya Boutique Villa www.udayaresidence.com or similar Bambu Battambang Hotel www.bambuhotel.com Hotel La Villa Battambang www.lavilla-battambang.net Battambang or similar Including : Excluding : 5 nights accommodation (with daily breakfast) Air ticket, visa fee and travel insurance Private transport for tour/airport transfers Additional meals not mentioned in the program Certified Tour Guide Additional beverages which is not included Entrance fee for Angkor Archeological Park Hotel early check in/late check out Entrance fee / boat rides for Tonle Sap Personal expenses Admission Fee for Kulen Mountain National Park Tips & gratuities Meals as mentioned ( 5B / 2L / 2D) Other services not listed in inclusive column Special visit & interaction as per arrangement in Battambang SRG Holidays Cambodia Page 1 PMT Address: 51, 7 Makara Road, Wat B SRG HOLIDAYS CAMBODIA Hotline : (855) 10 435331 l (855) 11 435331 l (855) 12 435331 Email : [email protected] | [email protected] Address : 20 Anson Place, Sala Konseng, Sangkat Svay Dangkum, Siem Reap, 17000 Cambodia. -

Sacred Connections 2 Programs May 12Th to May 25Th 2022 September 13Th to September 27Th 2022

Sacred Connections 2 programs May 12th to May 25th 2022 September 13th to September 27th 2022 DAY ONE, ATHENS… Our journey will begin in the beautiful ancient city of Athena. Settle into your room at the hotel and join us at 6.30pm to meet the group. There will be welcome drinks and nibbles before we step out for the evening for our first meal together. We will share the Greek food, Greek wine and connect as a group. After this we return to the hotel to settle back into our rooms in preparation for our first outing tomorrow. DAY TWO, DEPHI… We travel together today to the sacred town of Delphi, this famous ancient sanctuary that grew rich as the seat of Pythia, the oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient classical world. Moreover, the Greeks considered Delphi the navel (or centre) of the world, as represented by the stone monument known as the Omphalos of Delphi. In myths dating to the classical period of ancient Greece (510-323BC) Zeus determined the site of Delphi when he sought to find the centre of his “Grandmother Earth” (Gaia) He sent two eagles flying from the eastern and western extremities and the path of the eagles crossed over Dephi where the omphalos or navel of Gaia was found. When we arrive we will have the evening to take in the sites of this beautiful township, and go on a walking trip together. DAY THREE, DELPHI… Today we will take in the sacred site of Apollo and Tholos Temple, Sanctuary of Athena Pronaia. -

THE MAGIC of JEWELS and CHARMS Another Variety Had Alternate Red and White Stripes Or Veins."* Perhaps This "Emerald" Was a Variety of Jade, Or a Banded Jasper

THE MAGIC *OF JEWELS & CHAIQ^S V M \ ^\' h- / ^/ -f^/) <<f^'**^~. tl^'J t h- ^i^ >. /^ QEOKpiili.I)Ea^aCII^ A-303/C33 COPYRIGHT, 1915, BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY PUBLISHED NOVEMBER, 1915 i^V PRINTED BY J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY AT THE WASHINGTON SQUARE PRESS PHILADELPHIA, U. S. A. To THE Memory of THE LATE PROFESSOR THOMAS EGLESTON, Ph.D., LL.D. OFFICIBB DE LA LEGION d'hONNET7R AND FOtJNDEK OP THE SCHOOL OP MINES, COLUMBIA TJNIVEHSITT, AN ARDENT LOVEE OP MINERALS, KEENLY APPEECIATIVE OF PRECIOtrS STONES, AND A KINDLY FRIEND OF THE AUTHOR, THIS VOLUME IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED preface gjTEWEiLS, gems, stones, superstitions and astrological /J' lore are all so interwoven in history that to treat of either of them alone would mean to break the chain of as- sociation linking them one with the other. Beauty of color or lustre in a stone or some quaint form attracts the eye of the savage, and his choice of material for ornament or adornment is also conditioned by the tough- ness of some stones as compared with the facility with which others can be chipped or polished. Whereas a gem might be prized for its beauty by a single individual owner, a stone of curious and suggestive form sometimes claimed the reverence of an entire tribe, since it was thought to be the abode or the chosen instrument of some spirit or genius. Just as the appeal to higher powers for present help in pressing emergencies preceded the development of a formal religious faith, so this never-failing need of protectors or healers eventually led to the attribution of powers of protec- tion to the spirits of men and women who had led holy lives and about whose history legend had woven a web of pious imaginations at a time when poetic fancy reigned instead of historic record. -

Giorgio De Santillana, Hertha Von Dechend

Preface page v AS THE SENIOR, if least deserving, of the authors, I shall open the narrative. Over many years I have searched for the point where myth and science join. It was clear to me for a long time that the origins of science had their deep roots in a particular myth, that of invariance. The Greeks, as early as the 7th century B.C., spoke of the quest of their first sages as the Problem of the One and the Many, sometimes describing the wild fecundity of nature as the way in which the Many could be deduced from the One, sometimes seeing the Many as unsubstantial variations being played on the One. The oracular sayings of Heraclitus the Obscure do nothing but illustrate with shimmering paradoxes the illusory quality of "things" in flux as they were wrung from the central intuition of unity. Before him Anaximander had announced, also oracularly, that the cause of things being born and perishing is their mutual injustice to each other in the order of time, "as is meet," he said, for they are bound to atone forever for their mutual injustice. This was enough to make of Anaximander the acknowledged father of physical science, for the accent is on the real "Many." But it was true science after a fashion. Soon after, Pythagoras taught, no less oracularly, that "things are numbers." Thus mathematics was born. The problem of the origin of mathematics has remained with us to this day. In his high old age, Bertrand Russell has been driven to avow: "I have wished to know how the stars shine. -

10 Day Pilgrimage to Greece in the Footsteps of St. Paul

10 Day Pilgrimage to Greece in the Footsteps of St. Paul Spiritual Director Rev. David Beaumont September 27th – October 6th, 2018 YOUR TRIP INCLUDES: Round trip air from New York 5 Star Hotels Breakfast & Dinner Daily (except dinner in Athens on October 4th) Air-conditioned motor coach English speaking guide Sightseeing as per itinerary Porterage of one piece of luggage at hotels All taxes and service charges Daily Mass and Rosary HIGHLIGHTS: Visit the major Orthodox Basilicas in Thessaloniki - St. Demetrius, St. Sofia and St. George Church Visit the Vlatadon Monastery to see the house of Jason where St. Paul lived in Thessaloniki Visit Kavala, ancient Neapolis and Philippi Visit the Prison where St. Paul and Silas were imprisoned Visit the Creek where St. Paul Christened Lydia, the first convert in Europe Visit ancient Macedonia, where Alexander the Great was proclaimed King Travel along the via Egnatia the road St. Paul followed to Veria Visit the Monastery of the Transfiguration of Jesus and Saint Stephen Monastery in Meteora this is a UNESCO World Heritage Site Visit the ancient Sanctuary of Delphi this is a UNESCO World Heritage Site Walking Tour of Nafplion Visit Corinth where St. Paul preached to the Corinthians Stop at Cenchreae port where St. Paul took a ship to Ephesus at the end of his Second Journey Tour of Athens & Cape Sounion And much, much more!!! Pilgrimage Price: $ 3,399.00 per person double or single Single Supplement $ 700.00 ITINERARY Thu, Sept 27th: New York/Thessaloniki - Depart on your overnight flight to Thessaloniki. Fri, Sept 28th: Thessaloniki - Arrival in Thessaloniki and transfer to hotel. -

Cambodia Itinerary

Cambodia — The Ancient Khmer Paradise Itinerary Days 1 & 2 Let the Journey begin! Depart New York and arrive in Siem Reap. Day 3 Arrive in Siem Reap and transfer to hotel. Siem Riep is the capital city of PO Box 448 Siem Reap Province and is located in Northwestern Cambodia. It is a Richmond, VT 05477 vibrant town surrounded by silk farms, fishing villages, rice-paddy fields, a 802. 434.5416 lively market and many Buddhist Pagodas. It is the Gateway to the World [email protected] Heritage site of Angkor Wat the ancient capital of the great Khmer Empire. Angkor without doubt, is one of the most magnificent wonders of the world. It is an archeologists treasure-throve. Located in a dense jungle, there are hundreds of awe-inspiring and enchanting temples in the area and they will be your classrooms each day. After lunch you will visit Wat Bo Pagoda, one of the oldest pagodas in town. Built in the 18th century and located in the heart of town, it contains a fabulous collection of Buddhist sculpture and wall-paintings. Here you will have an introduction to Theravada Buddhism, the Buddhism of Cambodia. Overnight – Siem Reap Day 4 After breakfast you will explore your first ancient temple, the early 10th century Prasat Kravan. Here you will learn how for nearly six centuries, between AD 802 and 1432, the great Khmer Empire was once the most powerful empire in Southeast Asia that extended from the South China Sea to the Bay of Bengal. Ancient Cambodia was highly influenced by India and many of the Khmer Kings built temples dedicated to the Hindu gods such as Shiva and Vishnu. -

The Sirius Mystery

SIRIUSM.htm file:///C|/Documents%20and%20Settings/Administrator/My%20Documents/emule/Incoming/SIRIUS_Mystery_Dogon_Robert_KG_Temple/SIRIUSM.htm (1 of 349)22/03/2005 01:32:09 SIRIUSM.htm ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My first thanks must go to my wife, Olivia, who has been an excellent proof- reader and collater and who made the greatest number of helpful suggestions concerning the manuscript. Two friends who read the book at an early stage and took extreme pains to be helpful, and devoted much of their time to writing out or explaining to me at length their lists of specific suggestions, are Adrian Berry of the London Telegraph, and Michael Scott of Tangier. The latter gave meticulous attention to details which few people would trouble to do with another's work. This book would never have been written without the material concerning the Dogon having been brought to my attention by Arthur M. Young of Philadelphia. He has helped and encouraged my efforts to get to the bottom of the mystery for years, and supplied me with invaluable materials, including the typescript of an English translation of Le Renard Pale by the anthropologists Griaule and Dieterlen, which enabled me to bring my survey up to date. Without the stimulus and early encouragement of Arthur C. Clarke of Ceylon, this book might not have found the motive force to carry it through many dreary years of research. My agent, Miss Anne McDermid, has been a model critic and adviser at all stages. Her enthusiasm and energy are matched only by her penetrating intuition and her skill at negotiation. -

Sacred Geography of the Ancient Greeks Astrological Symbolism In

SACRED GEOGRAPHY OF THE ANCIENT GREEKS SUNY Series in Western Esoteric Traditions David Appelbaum, editor Omphalos decoratedwith the "net." (COpl)from the Roman period, Museum of Delphi) SACRED GEOGRAPHY OF THE ANCIENT GREEKS Astrological Symbolism in Art, Architecture, and Landscape � F 1G7Lf '?,-- 'j .1 \ '/ , ) Jean Richer Translated by Christine Rhone STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRE�� f Published by State University of New York Press, Albany ©1994 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address State University of New York Press, State University Plaza, Albany, N.Y., 12246 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Richer, Jean, 1915- [Geographie sacree du monde grec. English] Sacred geography of the ancient Greeks: astrological symbolism in art, architecture, and landscape / Jean Richer; translated by Christine Rhone. p. cm. - (SUNY series in Western esoteric traditions) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-2023-X - ISBN 0-7914-2024-8 (pbk.) 1. Astrology/Greek. 2. Sacred space-Greece. 3. Shrines Greece. 4. Artand religion-Greece. 5. Gretfe-Religion. " ! I. Title. n. Series. 1 994 f.�C;'� �� :;:;�2� 1) 094 �;:60 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents List of Maps xi Foreword xxi Translator's Preface xxvii Preface xxxi Chapter 1. Theory of Alignments 1 1. Delphi: Apollo and Athena 1 2. The Meridian of Delphi: Te mpe-Delphi-Sparta-Cape Taenarum 2 3.