Articles Congressional Disclosure of Time Spent Fundraising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

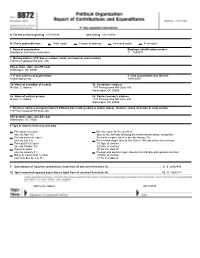

A for the Period Beginning 01/01/2014 and Ending 03/31/2014

A For the period beginning 01/01/2014 and ending 03/31/2014 B Check applicable box: ✔ Initial report Change of address Amended report Final report 1 Name of organization Employer identification number Republican Governors Association 11 - 3655877 2 Mailing address (P.O. box or number, street, and room or suite number) 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20006 3 E-mail address of organization: 4 Date organization was formed: [email protected] 10/04/2002 5a Name of custodian of records 5b Custodian's address Michael G. Adams 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 Washington, DC 20006 6a Name of contact person 6b Contact person's address Michael G. Adams 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 Washington, DC 20006 7 Business address of organization (if different from mailing address shown above). Number, street, and room or suite number 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20006 8 Type of report (check only one box) ✔ First quarterly report Monthly report for the month of: (due by April 15) (due by the 20th day following the month shown above, except the Second quarterly report December report, which is due by January 31) (due by July 15) Pre-election report (due by the 12th or 15th day before the election) Third quarterly report (1) Type of election: (due by October 15) (2) Date of election: Year-end report (3) For the state of: (due by January 31) Post-general election report (due by the 30th day after general election) Mid-year report (Non-election (1) Date of election: year only-due by July 31) (2) For the state of: 9 Total amount of reported contributions (total from all attached Schedules A) .......................................................................... -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 111 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 111 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 156 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, MAY 11, 2010 No. 70 House of Representatives The House met at 12:30 p.m. and was NET REGULATION WILL HARM turned it over to the private sector and called to order by the Speaker. INVESTMENT AND INNOVATION lifted restrictions on its use by com- The SPEAKER pro tempore (Ms. mercial entities and the public. The f MARKEY of Colorado). The Chair recog- unregulated Internet is now starting to help spur a new technological revolu- MORNING-HOUR DEBATE nizes the gentleman from Florida (Mr. STEARNS) for 5 minutes. tion in this country. Where there were The SPEAKER. Pursuant to the Mr. STEARNS. Madam Speaker, a re- once separate phone, cable, wireless, order of the House of January 6, 2009, cent announcement by FCC Chairman and other industries providing distinct the Chair will now recognize Members Genachowski to impose new, burden- and separate services, we’re now seeing from lists submitted by the majority some regulation on the Internet and on a confluence and a blur of providers all and minority leaders for morning-hour Internet transmission appears to me to competing against each other for con- debate. be a political maneuver to regulate the sumers, offering broadband, voice, Internet. Several weeks ago, he indi- video services, and much more. f cated he was not going to push for net The Apple iPod is a perfect example of the confluence of the Internet, the FISCAL RESPONSIBILITY regulation. -

The Rise and Impact of Fact-Checking in U.S. Campaigns by Amanda Wintersieck a Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment O

The Rise and Impact of Fact-Checking in U.S. Campaigns by Amanda Wintersieck A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved April 2015 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Kim Fridkin, Chair Mark Ramirez Patrick Kenney ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2015 ABSTRACT Do fact-checks influence individuals' attitudes and evaluations of political candidates and campaign messages? This dissertation examines the influence of fact- checks on citizens' evaluations of political candidates. Using an original content analysis, I determine who conducts fact-checks of candidates for political office, who is being fact- checked, and how fact-checkers rate political candidates' level of truthfulness. Additionally, I employ three experiments to evaluate the impact of fact-checks source and message cues on voters' evaluations of candidates for political office. i DEDICATION To My Husband, Aza ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my sincerest thanks to the many individuals who helped me with this dissertation and throughout my graduate career. First, I would like to thank all the members of my committee, Professors Kim L. Fridkin, Patrick Kenney, and Mark D. Ramirez. I am especially grateful to my mentor and committee chair, Dr. Kim L. Fridkin. Your help and encouragement were invaluable during every stage of this dissertation and my graduate career. I would also like to thank my other committee members and mentors, Patrick Kenney and Mark D. Ramirez. Your academic and professional advice has significantly improved my abilities as a scholar. I am grateful to husband, Aza, for his tireless support and love throughout this project. -

Big Business Ballot Bullies in 2016 State Ballot Initiative Races, Corporate-Backed Groups’ Campaign War Chests Outmatch Their Opposition by an Average of 10-To-1

September 28, 2016 www.citizen.org Big Business Ballot Bullies In 2016 State Ballot Initiative Races, Corporate-Backed Groups’ Campaign War Chests Outmatch Their Opposition by an Average of 10-to-1 Acknowledgments This report was written by Rick Claypool, research director for Public Citizen’s president’s office and edited by Robert Weissman, president of Public Citizen. About Public Citizen Public Citizen is a national nonprofit organization with more than 400,000 members and supporters. We represent consumer interests through lobbying, litigation, administrative advocacy, research, and public education on a broad range of issues including consumer rights in the marketplace, product safety, financial regulation, worker safety, safe and affordable health care, campaign finance reform and government ethics, fair trade, climate change, and corporate and government accountability. Public Citizen 1600 20th St. NW Washington, D.C. 20009 P: 202-588-1000 http://www.citizen.org © 2016 Public Citizen. Public Citizen Big Business Ballot Bullies Table of Contents Key Findings .............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Wimbledon: Second Williams Sister Still in Tourney /B1

Wimbledon: Second Williams sister still in tourney /B1 WEDNESDAY TODAY CITRUS COUNTY & next morning HIGH 85 Very windy; showers LOW likely and a slight chance of storms. 74 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com JUNE 27, 2012 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOLUME 117 ISSUE 325 NEWS BRIEFS Citrus County Bracing for Debby in state of emergency Due to expected high winds and coastal storm flooding in low-lying areas on the west side of Citrus County, the Board of County Commissioners unanimously voted to de- clare a local State of Emergency for Citrus County. This event declaration will last for seven days. Although no mandatory evacuations have been ordered, emergency man- agement officials are opening a special-needs shelter at the Renais- sance Center in Lecanto at 3630 W. Educational Path, and a pet-friendly/ general population shelter at Lecanto Primary School at 3790 W. Educational Path, Lecanto. Both shelters opened at 7 p.m. Tuesday. More information re- garding shelter openings and evacuations will be activated and distributed through the Citrus County Sheriff’s Office. Citizens may call the Sheriff’s Of- fice Citizen Information Lines at 352-527-2106 or DAVE SIGLER/Chronicle 352-746-5470. Doreen Mylin, owner of Magic Manatee Marina, waits Tuesday night in hopes her husband could move two forklifts away from the rising waters along the Homosassa River. “The ‘no-name’ storm was worst. This will be the second-worst,” Mylin said. —From staff reports Debby’s tropical weather brings flooding to portions of Citrus County INSIDE MIKE WRIGHT The high tide Tuesday night was expected stein said, referring to coastal residents who LOCAL NEWS: Staff Writer to bring 3 to 5 feet additional water to areas have seen water rise steadily since Sunday such as Homosassa and Crystal River that al- when the area was soaked with rain by Debby. -

Back Story: Lessons from the Colbert Super

LESSONS FROM THE COLBERT SUPERPAC BY ERIN BARNETT, ESQ. Federal campaign fi nance laws sure are tricky, and the 2010 Obama, Priorities USA Action, is headed by former Obama press United States Supreme Court decision, Citizens United v. Federal secretary, Bill Burton. Election Commission, has only muddied the waters. So it’s a In addition to having the freedom to accept unlimited good thing sharp legal minds, such as Stephen Colbert, host of amounts of contributions, Super PACs also have the advantage Comedy Central’s “The Colbert Report”, are around to show us of creating the impression of distance between a candidate and how it is all supposed to work. his or her donors. An entertaining Under Citizens United, certain example of this occurred when entities known as political action the famed legal brothel Moonlite committees (PACs) may now raise Bunny Ranch was requested by unlimited amounts of contributions the Ron Paul campaign to donate, received from individuals, not to the campaign directly, corporations and unions for the but to a Ron Paul-supporting purpose of supporting a candidate Super PAC. Donors looking (such as the purchase of TV ad for complete anonymity may space), but are prohibited from consider donating to a 501(c)(4) donating directly to particular organization associated with the campaigns. Such PACs, dubbed Super PAC the donor hopes to “Super PACs,” differ from benefi t; a 501(c)(4) is not required traditional PACs that can donate to meet the donor-disclosure directly to a particular campaign, requirements of Super PACs, but but cannot accept corporate or can nonetheless donate to Super union donations. -

ALABAMA Senators Jeff Sessions (R) Methodist Richard C. Shelby

ALABAMA Senators Jeff Sessions (R) Methodist Richard C. Shelby (R) Presbyterian Representatives Robert B. Aderholt (R) Congregationalist Baptist Spencer Bachus (R) Baptist Jo Bonner (R) Episcopalian Bobby N. Bright (D) Baptist Artur Davis (D) Lutheran Parker Griffith (D) Episcopalian Mike D. Rogers (R) Baptist ALASKA Senators Mark Begich (D) Roman Catholic Lisa Murkowski (R) Roman Catholic Representatives Don Young (R) Episcopalian ARIZONA Senators Jon Kyl (R) Presbyterian John McCain (R) Baptist Representatives Jeff Flake (R) Mormon Trent Franks (R) Baptist Gabrielle Giffords (D) Jewish Raul M. Grijalva (D) Roman Catholic Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Roman Catholic Harry E. Mitchell (D) Roman Catholic Ed Pastor (D) Roman Catholic John Shadegg (R) Episcopalian ARKANSAS Senators Blanche Lincoln (D) Episcopalian Mark Pryor (D) Christian Representatives Marion Berry (D) Methodist John Boozman (R) Baptist Mike Ross (D) Methodist Vic Snyder (D) Methodist CALIFORNIA Senators Barbara Boxer (D) Jewish Dianne Feinstein (D) Jewish Representatives Joe Baca (D) Roman Catholic Xavier Becerra (D) Roman Catholic Howard L. Berman (D) Jewish Brian P. Bilbray (R) Roman Catholic Ken Calvert (R) Protestant John Campbell (R) Presbyterian Lois Capps (D) Lutheran Dennis Cardoza (D) Roman Catholic Jim Costa (D) Roman Catholic Susan A. Davis (D) Jewish David Dreier (R) Christian Scientist Anna G. Eshoo (D) Roman Catholic Sam Farr (D) Episcopalian Bob Filner (D) Jewish Elton Gallegly (R) Protestant Jane Harman (D) Jewish Wally Herger (R) Mormon Michael M. Honda (D) Protestant Duncan Hunter (R) Protestant Darrell Issa (R) Antioch Orthodox Christian Church Barbara Lee (D) Baptist Jerry Lewis (R) Presbyterian Zoe Lofgren (D) Lutheran Dan Lungren (R) Roman Catholic Mary Bono Mack (R) Protestant Doris Matsui (D) Methodist Kevin McCarthy (R) Baptist Tom McClintock (R) Baptist Howard P. -

Conservation Report Card

2009-2010 CONSERVATION REPORT CARD Evaluating the 111th Congress efenders of Wildlife Action Fund Deducates the public about conservation issues and generates grassroots efforts to ensure that members of Congress and the president hear from constituents on pending legislation and regulations. Defenders of Wildlife Action Fund advocates in Washington, D.C., for legislation to safeguard wildlife and habitat and fights efforts to undermine conservation laws, such as the landmark Endangered Species Act. The Action Fund also publishes the Conservation Report Card to help citizens hold their legislators accountable by providing information on how lawmakers voted on important conservation issues. An online version of the Conservation Report Card, which contains detailed and updated information about key votes, is available at www.defendersactionfund.org Defenders of Wildlife Action Fund is a 501(c)(4) organization with a segregated Section 527 account. © 2011 Defenders of Wildlife Action Fund 1130 17th Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 Photo: Hawksbill turtle © David Fleetham/naturepl.com FPOCert no. XXX-XXX-000 Printed on 100% post-consumer-waste, process-chlorine-free, recycled paper. he Defenders of Wildlife Action Fund’s 2009-2010 Conservation T Report Card measures the commitment of U.S. senators and representatives to wildlife and habitat conservation during the 111th Congress. It reviews six Senate votes and seven House votes on key conservation issues, providing a clear assessment of how well members of Congress are protecting wildlife and wild lands for future generations. The2009-2010 Conservation Report Card covers votes on important issues such as protecting polar bears, the world’s imperiled wild feline and canine species, and California sea otters; safeguarding wildlife and habitat in sensitive borderlands; addressing the impacts of climate change on wildlife; regulating greenhouse gas emissions; upholding the Endangered Species Act; and drilling for oil off our coasts. -

Election 2006

APPENDIX: CANDIDATE PROFILES BY STATE We analyzed the fair trade positions of candidates in each race that the Cook Political Report categorized as in play. In the profiles below, race winners are denoted by a check mark. Winners who are fair traders are highlighted in blue text. Alabama – no competitive races___________________________________________ Alaska_________________________________________________________________ Governor OPEN SEAT – incumbent Frank Murkowski (R) lost in primary and was anti-fair trade. As senator, Murkowski had a 100% anti-fair trade voting record. 9 GOP Sarah Palin’s trade position is unknown. • Democratic challenger Tony Knowles is a fair trader. In 2004, Knowles ran against Lisa Murkowski for Senate and attacked her for voting for NAFTA-style trade deals while in the Senate, and for accepting campaign contributions from companies that off-shore jobs.1 Arizona________________________________________________________________ Senate: Incumbent GOP Sen. Jon Kyl. 9 Kyl is anti-fair trade. Has a 100% anti-fair trade record. • Jim Pederson (D) is a fair trader. Pederson came out attacking Kyl’s bad trade record in closing week of campaign, deciding to make off-shoring the closing issue. On Nov. 3 campaign statement: “Kyl has repeatedly voted for tax breaks for companies that ship jobs overseas, and he has voted against a measure that prohibited outsourcing of work done under federally funded contracts,” said Pederson spokesman Kevin Griffis, who added that Pederson “wants more protections [in trade pacts] related to child labor rules and environmental safeguards to help protect U.S. jobs.”2 House Arizona 1: GOP Rep. Rick Renzi incumbent 9 Renzi is anti-fair trade. 100% bad trade vote record. -

Super Pac Contributions, Corruption, and the Proxy War Over Coordination

Legal Studies Research Paper Series No. 2014-11 SUPER PAC CONTRIBUTIONS, CORRUPTION, AND THE PROXY WAR OVER COORDINATION Richard L. Hasen [email protected] University of California, Irvine ~ School of Law The paper can be downloaded free of charge from SSRN at: Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2383452 Preliminary draft: January 21, 2014 Forthcoming: DUKE JOURNAL OF CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AND PUBLIC POLICY (symposium) (2014) Please do not cite or quote without permission ESSAY SUPER PAC CONTRIBUTIONS, CORRUPTION, AND THE PROXY WAR OVER COORDINATION RICHARD L. HASEN* I. WHY LIMIT SUPER PAC CONTRIBUTIONS? In 1995, journalist and supply-side economics enthusiast Jude Wanniski wrote an op-ed in the New York Times noting the anomaly that under the Supreme Court’s campaign finance rulings,1 billionaire Steve Forbes could spend $25 million (or any amount) supporting his own candidacy to be president, but he could donate only $1,000 to Jack Kemp’s presidential campaign.2 Forbes believed Kemp would have been a more effective candidate to promote Forbes’ views, and Wanniski suggested that Forbes should have been able to give $25 million directly to Kemp to bankroll a Kemp candidacy.3 Wanniski saw nothing wrong with Forbes giving Kemp so much money: “Wouldn’t we expect President Kemp, with his $25 million check from Mr. Forbes to take a call from him sooner than from, say, Mr. Business Week? But so what? His views are closer to Forbe’s than to Business Week’s, with or without campaign contributions.”4 Wanniski’s views appear to be in the minority, at least judged by longstanding laws imposing individual contribution limitations in federal * Chancellor’s Professor of Law and Political Science, UC Irvine School of Law. -

Top Ten Ethics Scandals 2010

CREW’S TOP TEN ETHICS SCANDALS 2010 1400 EYE STREET NW, SUITE 450 WASHINGTON DC 20005 www.citizensforethics.org CREW’S TOP TEN SCANDALS OF 2010 Laugh ‘Til It Hurts Tickle fights are no laughing matter when they involve a congressman and his staff. Rep. Eric Massa (D-NY) resigned from Congress on March 8, 2010, following allegations of sexual harassment and bizarre behavior. His ever-shifting reasons for stepping down included his resurgent cancer, the toxic atmosphere of Washington, a pending ethics investigation, and, most colorfully, threats from a naked Rahm Emanuel.1 The laundry list of allegations against him paint a picture of a lawmaker out of control, whose crude comments and unpredictable actions had his staff on edge for almost a year.2 Rep. Massa, who lived with some of his staffers, was accused of a host of potential violations of House ethics rules, including groping staff members and using inappropriate language in his office.3 But it wasn’t until an anonymous online comment accused Rep. Massa of soliciting sex from a bartender that Rep. Massa’s staff contacted the office of House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer about the congressman’s behavior.4 When told about the allegations the week of February 8, 2010, Rep. Hoyer gave Rep. Massa and his staff 48 hours to report the matter to the ethics committee or he would do so himself.5 The ethics committee publicly confirmed the investigation into Rep. Massa on March 4, and the congressman announced his resignation on March 5.6 After Rep. Massa’s resignation, Republicans pushed for an investigation into when House Democratic leaders first learned of the allegations against Rep. -

Removing Individual and Party Limits on Contributions to Presidential Campaigns

Facing the Coordination Reality: Removing Individual and Party Limits on Contributions to Presidential Campaigns BY ZACHARY MORRISON* Since Citizens United, a new era of campaigning has emerged in which traditional campaign functions have been outsourced to candidate-centric outside groups. In the 2016 presidential election, ten campaigns had raised less money than their allied Super PACs and other outside groups. Federal election regulations that restrict coordination between these outside groups and campaigns are outdated and poorly enforced. American democracy is weakened by this unprecedented electoral activity because of decreased donor transparency, increased negativity without accountability, and voter confusion. This Note concludes, after examining outside group political activity in the 2012 and 2016 presidential cycles, that candidate-centric outside groups create the same risk of corruption as direct contributions to campaigns. Therefore, this Note proposes that proponents of stricter campaign finance regulation should consider removing limits on individual and political party contributions to presidential campaigns. Allowing individuals and parties to provide unlimited funds to campaigns would diminish the appeal of outside groups and increase the political pressure on campaigns to disavow their use. This realistic, if not pessimistic, proposal offers a simple legislative solution to some of the concerning elements of an increased reliance on outside groups, while * Farnsworth Note Competition Winner, 2019. J.D. Candidate 2019, Columbia Law School. The author thanks Professor Richard Briffault for not only his advice and guidance, but also his academic contributions to the subject that inspired this project. Special thanks to the editors and staff of the Columbia Journal of Law and Social Problems for their invaluable feedback and tireless commitment to the process.