Arbitration for the “Afflicted” — the Viability of Arbitrating Defamation and Libel Claims Considering IPSO’S Pilot Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

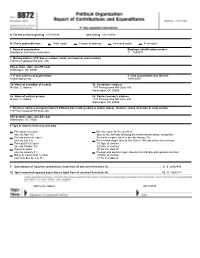

A for the Period Beginning 01/01/2014 and Ending 03/31/2014

A For the period beginning 01/01/2014 and ending 03/31/2014 B Check applicable box: ✔ Initial report Change of address Amended report Final report 1 Name of organization Employer identification number Republican Governors Association 11 - 3655877 2 Mailing address (P.O. box or number, street, and room or suite number) 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20006 3 E-mail address of organization: 4 Date organization was formed: [email protected] 10/04/2002 5a Name of custodian of records 5b Custodian's address Michael G. Adams 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 Washington, DC 20006 6a Name of contact person 6b Contact person's address Michael G. Adams 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 Washington, DC 20006 7 Business address of organization (if different from mailing address shown above). Number, street, and room or suite number 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20006 8 Type of report (check only one box) ✔ First quarterly report Monthly report for the month of: (due by April 15) (due by the 20th day following the month shown above, except the Second quarterly report December report, which is due by January 31) (due by July 15) Pre-election report (due by the 12th or 15th day before the election) Third quarterly report (1) Type of election: (due by October 15) (2) Date of election: Year-end report (3) For the state of: (due by January 31) Post-general election report (due by the 30th day after general election) Mid-year report (Non-election (1) Date of election: year only-due by July 31) (2) For the state of: 9 Total amount of reported contributions (total from all attached Schedules A) .......................................................................... -

The Rise and Impact of Fact-Checking in U.S. Campaigns by Amanda Wintersieck a Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment O

The Rise and Impact of Fact-Checking in U.S. Campaigns by Amanda Wintersieck A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved April 2015 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Kim Fridkin, Chair Mark Ramirez Patrick Kenney ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2015 ABSTRACT Do fact-checks influence individuals' attitudes and evaluations of political candidates and campaign messages? This dissertation examines the influence of fact- checks on citizens' evaluations of political candidates. Using an original content analysis, I determine who conducts fact-checks of candidates for political office, who is being fact- checked, and how fact-checkers rate political candidates' level of truthfulness. Additionally, I employ three experiments to evaluate the impact of fact-checks source and message cues on voters' evaluations of candidates for political office. i DEDICATION To My Husband, Aza ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my sincerest thanks to the many individuals who helped me with this dissertation and throughout my graduate career. First, I would like to thank all the members of my committee, Professors Kim L. Fridkin, Patrick Kenney, and Mark D. Ramirez. I am especially grateful to my mentor and committee chair, Dr. Kim L. Fridkin. Your help and encouragement were invaluable during every stage of this dissertation and my graduate career. I would also like to thank my other committee members and mentors, Patrick Kenney and Mark D. Ramirez. Your academic and professional advice has significantly improved my abilities as a scholar. I am grateful to husband, Aza, for his tireless support and love throughout this project. -

Big Business Ballot Bullies in 2016 State Ballot Initiative Races, Corporate-Backed Groups’ Campaign War Chests Outmatch Their Opposition by an Average of 10-To-1

September 28, 2016 www.citizen.org Big Business Ballot Bullies In 2016 State Ballot Initiative Races, Corporate-Backed Groups’ Campaign War Chests Outmatch Their Opposition by an Average of 10-to-1 Acknowledgments This report was written by Rick Claypool, research director for Public Citizen’s president’s office and edited by Robert Weissman, president of Public Citizen. About Public Citizen Public Citizen is a national nonprofit organization with more than 400,000 members and supporters. We represent consumer interests through lobbying, litigation, administrative advocacy, research, and public education on a broad range of issues including consumer rights in the marketplace, product safety, financial regulation, worker safety, safe and affordable health care, campaign finance reform and government ethics, fair trade, climate change, and corporate and government accountability. Public Citizen 1600 20th St. NW Washington, D.C. 20009 P: 202-588-1000 http://www.citizen.org © 2016 Public Citizen. Public Citizen Big Business Ballot Bullies Table of Contents Key Findings .............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Wimbledon: Second Williams Sister Still in Tourney /B1

Wimbledon: Second Williams sister still in tourney /B1 WEDNESDAY TODAY CITRUS COUNTY & next morning HIGH 85 Very windy; showers LOW likely and a slight chance of storms. 74 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com JUNE 27, 2012 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOLUME 117 ISSUE 325 NEWS BRIEFS Citrus County Bracing for Debby in state of emergency Due to expected high winds and coastal storm flooding in low-lying areas on the west side of Citrus County, the Board of County Commissioners unanimously voted to de- clare a local State of Emergency for Citrus County. This event declaration will last for seven days. Although no mandatory evacuations have been ordered, emergency man- agement officials are opening a special-needs shelter at the Renais- sance Center in Lecanto at 3630 W. Educational Path, and a pet-friendly/ general population shelter at Lecanto Primary School at 3790 W. Educational Path, Lecanto. Both shelters opened at 7 p.m. Tuesday. More information re- garding shelter openings and evacuations will be activated and distributed through the Citrus County Sheriff’s Office. Citizens may call the Sheriff’s Of- fice Citizen Information Lines at 352-527-2106 or DAVE SIGLER/Chronicle 352-746-5470. Doreen Mylin, owner of Magic Manatee Marina, waits Tuesday night in hopes her husband could move two forklifts away from the rising waters along the Homosassa River. “The ‘no-name’ storm was worst. This will be the second-worst,” Mylin said. —From staff reports Debby’s tropical weather brings flooding to portions of Citrus County INSIDE MIKE WRIGHT The high tide Tuesday night was expected stein said, referring to coastal residents who LOCAL NEWS: Staff Writer to bring 3 to 5 feet additional water to areas have seen water rise steadily since Sunday such as Homosassa and Crystal River that al- when the area was soaked with rain by Debby. -

Back Story: Lessons from the Colbert Super

LESSONS FROM THE COLBERT SUPERPAC BY ERIN BARNETT, ESQ. Federal campaign fi nance laws sure are tricky, and the 2010 Obama, Priorities USA Action, is headed by former Obama press United States Supreme Court decision, Citizens United v. Federal secretary, Bill Burton. Election Commission, has only muddied the waters. So it’s a In addition to having the freedom to accept unlimited good thing sharp legal minds, such as Stephen Colbert, host of amounts of contributions, Super PACs also have the advantage Comedy Central’s “The Colbert Report”, are around to show us of creating the impression of distance between a candidate and how it is all supposed to work. his or her donors. An entertaining Under Citizens United, certain example of this occurred when entities known as political action the famed legal brothel Moonlite committees (PACs) may now raise Bunny Ranch was requested by unlimited amounts of contributions the Ron Paul campaign to donate, received from individuals, not to the campaign directly, corporations and unions for the but to a Ron Paul-supporting purpose of supporting a candidate Super PAC. Donors looking (such as the purchase of TV ad for complete anonymity may space), but are prohibited from consider donating to a 501(c)(4) donating directly to particular organization associated with the campaigns. Such PACs, dubbed Super PAC the donor hopes to “Super PACs,” differ from benefi t; a 501(c)(4) is not required traditional PACs that can donate to meet the donor-disclosure directly to a particular campaign, requirements of Super PACs, but but cannot accept corporate or can nonetheless donate to Super union donations. -

Super Pac Contributions, Corruption, and the Proxy War Over Coordination

Legal Studies Research Paper Series No. 2014-11 SUPER PAC CONTRIBUTIONS, CORRUPTION, AND THE PROXY WAR OVER COORDINATION Richard L. Hasen [email protected] University of California, Irvine ~ School of Law The paper can be downloaded free of charge from SSRN at: Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2383452 Preliminary draft: January 21, 2014 Forthcoming: DUKE JOURNAL OF CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AND PUBLIC POLICY (symposium) (2014) Please do not cite or quote without permission ESSAY SUPER PAC CONTRIBUTIONS, CORRUPTION, AND THE PROXY WAR OVER COORDINATION RICHARD L. HASEN* I. WHY LIMIT SUPER PAC CONTRIBUTIONS? In 1995, journalist and supply-side economics enthusiast Jude Wanniski wrote an op-ed in the New York Times noting the anomaly that under the Supreme Court’s campaign finance rulings,1 billionaire Steve Forbes could spend $25 million (or any amount) supporting his own candidacy to be president, but he could donate only $1,000 to Jack Kemp’s presidential campaign.2 Forbes believed Kemp would have been a more effective candidate to promote Forbes’ views, and Wanniski suggested that Forbes should have been able to give $25 million directly to Kemp to bankroll a Kemp candidacy.3 Wanniski saw nothing wrong with Forbes giving Kemp so much money: “Wouldn’t we expect President Kemp, with his $25 million check from Mr. Forbes to take a call from him sooner than from, say, Mr. Business Week? But so what? His views are closer to Forbe’s than to Business Week’s, with or without campaign contributions.”4 Wanniski’s views appear to be in the minority, at least judged by longstanding laws imposing individual contribution limitations in federal * Chancellor’s Professor of Law and Political Science, UC Irvine School of Law. -

Removing Individual and Party Limits on Contributions to Presidential Campaigns

Facing the Coordination Reality: Removing Individual and Party Limits on Contributions to Presidential Campaigns BY ZACHARY MORRISON* Since Citizens United, a new era of campaigning has emerged in which traditional campaign functions have been outsourced to candidate-centric outside groups. In the 2016 presidential election, ten campaigns had raised less money than their allied Super PACs and other outside groups. Federal election regulations that restrict coordination between these outside groups and campaigns are outdated and poorly enforced. American democracy is weakened by this unprecedented electoral activity because of decreased donor transparency, increased negativity without accountability, and voter confusion. This Note concludes, after examining outside group political activity in the 2012 and 2016 presidential cycles, that candidate-centric outside groups create the same risk of corruption as direct contributions to campaigns. Therefore, this Note proposes that proponents of stricter campaign finance regulation should consider removing limits on individual and political party contributions to presidential campaigns. Allowing individuals and parties to provide unlimited funds to campaigns would diminish the appeal of outside groups and increase the political pressure on campaigns to disavow their use. This realistic, if not pessimistic, proposal offers a simple legislative solution to some of the concerning elements of an increased reliance on outside groups, while * Farnsworth Note Competition Winner, 2019. J.D. Candidate 2019, Columbia Law School. The author thanks Professor Richard Briffault for not only his advice and guidance, but also his academic contributions to the subject that inspired this project. Special thanks to the editors and staff of the Columbia Journal of Law and Social Problems for their invaluable feedback and tireless commitment to the process. -

Super Pacs and 501(C) Groups in the 2016 Election

Super PACs and 501(c) Groups in the 2016 Election David B. Magleby* Brigham Young University Paper presented at the “State of the Parties: 2016 and Beyond”, Ray C. Bliss Institute of Applied Politics, University of Akron. November 9-10, 2017. *I would like to acknowledge the research assistance of Hyrum Clarke, Ben Forsgren, John Geilman, Jake Jensen, Jacob Nielson, Blake Ringer, Alena Smith, Wen Je (Fred) Tan, and Sam Williams all BYU undergraduates. Data made available by the Center for Responsive Politics was helpful as were two interviews with Robert Maguire, whose expertise in political nonprofits was informative. 1 Super PACs and 501(c) Groups in the 2067 Election David B. Magleby Brigham Young University In only a short period of time, Super PACs have come to be one of the most important parts of American electoral politics. They raise and spend large sums of money in competitive federal elections. They have become fully integrated teammates with candidates, party leaders, and interest groups. While initially they were most visible in paying for television advertising, by 2016 they expanded their scope by providing a wide variety of campaign services once thought to be funded by candidate campaign committees (campaign events) or party committees, (get-out-the-vote, voter registration, list development). Where does the money come from that funds Super PACs and other outside groups? While much of the attention on sources of funding for Super PACs was initially on corporations and unions, the reality has been that most of the funding for Super PACs has been individuals. Publicly traded corporations have been infrequent funders of Super PACs, while unions have been more active in using Super PACs. -

How Shady Operators Used Sham Non-Profits and Fake Corporations to Funnel Mystery Money Into the 2012 Elections

TOP SECRET How Shady Operators Used Sham Non-profits and Fake Corporations to Funnel Mystery Money into the 2012 Elections How Shady Operators Used Sham Non-profits and Fake Corporations to Funnel Mystery Money into the 2012 Elections Brendan Fischer, Staff Counsel Center for Media and Democracy Blair Bowie, Democracy Advocate U.S. PIRG Education Fund Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank Mike Russo of the U.S. PIRG Education Fund and Lisa Graves of the Center for Media and Democracy for their thoughtful review, U.S. PIRG Education Fund Democracy Intern Steven Franks for wading through large amounts of data on shell corporations, and the data team at Demos for helping to provide specific figures. The Center for Media and Democracy (CMD) is a nonpartisan, non-profit watchdog and investigative reporting group based in Madison, Wiscon- sin, which publishes PRwatch.org, ALECexposed.org, SourceWatch.org, and BanksterUSA.org. CMD has received numerous awards for its investigations into corporate influence on democracy, policy or media, including the “Izzy” I.F. Stone Award for outstanding achievement in independent media, the Sidney Award for investigative journalism (shared jointly with The Nation magazine), and the Professional Freedom and Responsibility Award from the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, Culture and Critical Studies Division. U.S. PIRG Education Fund conducts research and public education on behalf of consumers and the public interest. Our research, analysis, reports and out- reach serve as counterweights to the influence of powerful special interests that threaten our health, safety or well-being. With public debate around important issues often dominated by special interests pursuing their own narrow agendas, U.S. -

How Political Organizations Profiteer Off the First Amendment and What Congress Should Do About It

FIRST AMENDMENT LAW REVIEW Volume 12 | Issue 3 Article 7 3-1-2014 Put Your Mouth Where Your Money Is: How Political Organizations Profiteer off the irsF t Amendment and What Congress Should Do about It Philip A. Thompson Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/falr Part of the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Philip A. Thompson, Put Your Mouth Where Your Money Is: How Political Organizations Profiteer off ht e First Amendment and What Congress Should Do about It, 12 First Amend. L. Rev. 725 (2014). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/falr/vol12/iss3/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in First Amendment Law Review by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Put Your Mouth Where Your Money Is: How Political Organizations Profiteer Off the First Amendment and What Congress Should Do About It PhilipA. Thompson* INTRODUCTION Political organizations, such as political actions committees (PAC), super PACs, and 501(c)s raise and spend money to advocate for or against issues and candidates. These organizations are regulated subject to the First Amendment's speech clause and certain tax laws. Recently, these organizations-especially super PACs and 501(c)s- have become significant outlets for core political speech. For instance, in the 2010 election cycle, "[seventy-nine] groups registered as super PACs spent a total of approximately $90.4 million."I In the 2012 election cycle, "1,310 groups organized as Super PACs have reported total receipts of $828,224,700 and total independent expenditures of $609,417,654 . -

Entity Name (BCDA) BATIBO CULTURAL and DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION 01:CONCEPT LLC 1 800 COLLECT INC

Entity Name (BCDA) BATIBO CULTURAL AND DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION 01:CONCEPT LLC 1 800 COLLECT INC. 1 CLEAR SOLUTION, LLC 10 GRANT CIRCLE LLC 10 Grant KNS LLC 1000 URBAN SCHOLARS 1001 16TH STREET LLC 1001 H ST, LLC 1001 L STREET SE, L.L.C. 1001 SE Holdings LLC 1003 RHODE ISLAND LLC 1005 E Street SE L.L.C. 1005 Rhode Island Ave NE Partners LLC 1007 Irving Street NE Partners LLC 1007-1009 H STREET, NE LLC 100TH BOMB GROUP FOUNDATION INC. 101 5th Street NE LLC 101 CONSTITUTION Trust 101 WAYNE LLC 1010 MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE CONDOMINIUM UNIT OWNERS ASSOCIATION 1010 V LLC 1011 Otis Place L.L.C. 1011 Otis Place NW LLC 1012 9th St. Builders LLC 1015 Euclid Street NW LLC 1015 U STREET LLC 1016 16TH STREET CONDOMINIUM LLC 1016 7TH STREET LLC 1019 VENTURES LLC 102 MILITARY ROAD LLC 1020 45th St. LLC 1021 48TH ST NE LLC 1022 47TH STREET LLC 1026 45th St. LLC 1030 TAUSSIG PLACE, LLC 1030 W. 15TH LLC 1033 BLADENSBURG ROAD, NE LLC 1035 48th Street LLC 104 13TH STREET LLC 104 Kennedy Street LLC 1042 LIMITED PARTNERSHIP LLP 105 35th Street N.E. LLC 1061 INN, LLC 107 LLC 1070 THOMAS JEFFERSON ASSOCIATES LIMITED PARTNERSHIP 1075 KENILWORTH AVENUE LLC 1085805 SE LLC 1090 Vermont LLC 1090 VERMONT AVENUE GP LLC 109-187 35TH STREET N.E. BENEFICIARY LLC 109-187 35TH STREET N.E. TRUSTEE LLC 10TH & M STREET CONDOMINIUMS LLC 10th Street Parking Cooperative Association, Inc. 1100 21ST STREET ASSOCIATES LIMITED PARTNERSHIP 1100 FIRST INC. -

Articles Congressional Disclosure of Time Spent Fundraising

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CJP\23-1\CJP101.txt unknown Seq: 1 8-NOV-13 11:55 ARTICLES CONGRESSIONAL DISCLOSURE OF TIME SPENT FUNDRAISING Brent Ferguson* This Article advocates passage of a law requiring members of Con- gress to disclose the amount of time they spend fundraising. In the wake of Citizens United and other court decisions severely limiting lawmakers’ ability to regulate campaign spending, many schol- ars have turned their focus to campaign finance disclosure laws. Ac- cording to some, laws requiring campaigns and donors to reveal the source of contributions and expenditures are the last bastion of federal campaign finance law. Yet despite a history of broad acceptance, disclo- sure laws rest on an increasingly shaky foundation. The most troubling aspect of current disclosure law is that it con- tains loopholes so obvious and irresistible that many political players choose to spend dark money, the source of which is unidentified. Fur- ther, some argue that even when the source of political spending is dis- closed, the information provided to the electorate is of questionable usefulness for a host of reasons. Finally, opponents of disclosure laws point to their potential chilling effect and threats of retaliation that can occur when the public learns who supported a certain candidate or bal- lot measure. Even those who support disclosure laws have recently con- ceded that perhaps disclosure requirements should encompass only large spenders rather than those contributing only a few hundred dollars. For these reasons, there have been calls to reform federal disclo- sure law so it is more properly tailored to serve its goals without chilling speech.