Removing Individual and Party Limits on Contributions to Presidential Campaigns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cnn Debate Live Stream

Cnn debate live stream Continue Cutting cable is not too difficult if you are watching sports, in which case it is a nightmare. Huh989 over at Hackerspace wants to know: how do you stream sports, and sports packages are there worth it? Cable TV is insanely expensive, and with all the cheapest video services out there, it's easy to cut... MorePhoto Ed Yourdon.I have two things that, until recently, combined to reduce the quality of my life. These two things More Today is the final Republican debate before Super Tuesday-day a whopping twelve states and one U.S. territory will have either a primary or caucus. That's how to stream it online without cable. Before the general election, each state has its own primaries and caucuses, and today's Iowa caucuses ... Read more in the debate of the other five Republican presidential candidates: Ben Carson, Marco Rubio, Donald Trump, Ted Cruz and John Kasich. This is the last debate for Super Tuesday next week. On Tuesday, March 1, twelve states (Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Colorado, Georgia, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont and Virginia) and one U.S. territory (American Samoa) will hold either primary or caucuses. If you live in any of these areas, this is your last chance to watch the debate before it's time to help choose your candidate. The debate begins at 8:30 p.m. ET / 5:30 p.m. PT. Here's how you can stream it online: If you're a satellite radio subscriber, you can listen on SiriusXM Channel 115. -

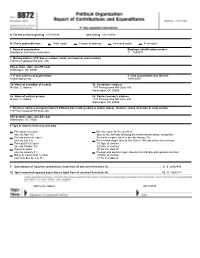

A for the Period Beginning 01/01/2014 and Ending 03/31/2014

A For the period beginning 01/01/2014 and ending 03/31/2014 B Check applicable box: ✔ Initial report Change of address Amended report Final report 1 Name of organization Employer identification number Republican Governors Association 11 - 3655877 2 Mailing address (P.O. box or number, street, and room or suite number) 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20006 3 E-mail address of organization: 4 Date organization was formed: [email protected] 10/04/2002 5a Name of custodian of records 5b Custodian's address Michael G. Adams 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 Washington, DC 20006 6a Name of contact person 6b Contact person's address Michael G. Adams 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 Washington, DC 20006 7 Business address of organization (if different from mailing address shown above). Number, street, and room or suite number 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20006 8 Type of report (check only one box) ✔ First quarterly report Monthly report for the month of: (due by April 15) (due by the 20th day following the month shown above, except the Second quarterly report December report, which is due by January 31) (due by July 15) Pre-election report (due by the 12th or 15th day before the election) Third quarterly report (1) Type of election: (due by October 15) (2) Date of election: Year-end report (3) For the state of: (due by January 31) Post-general election report (due by the 30th day after general election) Mid-year report (Non-election (1) Date of election: year only-due by July 31) (2) For the state of: 9 Total amount of reported contributions (total from all attached Schedules A) .......................................................................... -

Beyond the Bully Pulpit: Presidential Speech in the Courts

SHAW.TOPRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 11/15/2017 3:32 AM Beyond the Bully Pulpit: Presidential Speech in the Courts Katherine Shaw* Abstract The President’s words play a unique role in American public life. No other figure speaks with the reach, range, or authority of the President. The President speaks to the entire population, about the full range of domestic and international issues we collectively confront, and on behalf of the country to the rest of the world. Speech is also a key tool of presidential governance: For at least a century, Presidents have used the bully pulpit to augment their existing constitutional and statutory authorities. But what sort of impact, if any, should presidential speech have in court, if that speech is plausibly related to the subject matter of a pending case? Curiously, neither judges nor scholars have grappled with that question in any sustained way, though citations to presidential speech appear with some frequency in judicial opinions. Some of the time, these citations are no more than passing references. Other times, presidential statements play a significant role in judicial assessments of the meaning, lawfulness, or constitutionality of either legislation or executive action. This Article is the first systematic examination of presidential speech in the courts. Drawing on a number of cases in both the Supreme Court and the lower federal courts, I first identify the primary modes of judicial reliance on presidential speech. I next ask what light the law of evidence, principles of deference, and internal executive branch dynamics can shed on judicial treatment of presidential speech. -

How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics

GETTY CORUM IMAGES/SAMUEL How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG How White Supremacy Returned to Mainstream Politics By Simon Clark July 2020 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Tracing the origins of white supremacist ideas 13 How did this start, and how can it end? 16 Conclusion 17 About the author and acknowledgments 18 Endnotes Introduction and summary The United States is living through a moment of profound and positive change in attitudes toward race, with a large majority of citizens1 coming to grips with the deeply embedded historical legacy of racist structures and ideas. The recent protests and public reaction to George Floyd’s murder are a testament to many individu- als’ deep commitment to renewing the founding ideals of the republic. But there is another, more dangerous, side to this debate—one that seeks to rehabilitate toxic political notions of racial superiority, stokes fear of immigrants and minorities to inflame grievances for political ends, and attempts to build a notion of an embat- tled white majority which has to defend its power by any means necessary. These notions, once the preserve of fringe white nationalist groups, have increasingly infiltrated the mainstream of American political and cultural discussion, with poi- sonous results. For a starting point, one must look no further than President Donald Trump’s senior adviser for policy and chief speechwriter, Stephen Miller. In December 2019, the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hatewatch published a cache of more than 900 emails2 Miller wrote to his contacts at Breitbart News before the 2016 presidential election. -

The Impact of Organizational Characteristics on Super PAC

The Impact of Organizational Characteristics on Super PAC Financing and Independent Expenditures Paul S. Herrnson University of Connecticut [email protected] Presented at the Meeting of the Campaign Finance Task Force, Bipartisan Policy Center, Washington, DC, April 21, 2017 (revised June 2017). 1 Exe cutive Summa ry Super PACs have grown in number, wealth, and influence since the Supreme Court laid the foundation for their formation in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, and the decisions reached by other courts and the FEC clarified the boundaries of their political participation. Their objectives and activities also have evolved. Super PACs are not nearly as monolithic as they have been portrayed by the media. While it is inaccurate to characterize them as representative of American society, it is important to recognize that they vary in wealth, mission, structure, affiliation, political perspective, financial transparency, and how and where they participate in political campaigns. Organizational characteristics influence super PAC financing, including the sums they raise. Organizational characteristics also affect super PAC independent expenditures, including the amounts spent, the elections in which they are made, the candidates targeted, and the tone of the messages delivered. The super PAC community is not static. It is likely to continue to evolve in response to legal challenges; regulatory decisions; the objectives of those who create, administer, and finance them; and changes in the broader political environment. 2 Contents I. Introduction 3 II. Data and Methods 4 III. Emergence and Development 7 IV. Organizational Characteristics 11 A. Finances 11 B. Mission 14 C. Affiliation 17 D. Financial Transparency 19 E. -

The Rise and Impact of Fact-Checking in U.S. Campaigns by Amanda Wintersieck a Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment O

The Rise and Impact of Fact-Checking in U.S. Campaigns by Amanda Wintersieck A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved April 2015 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Kim Fridkin, Chair Mark Ramirez Patrick Kenney ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2015 ABSTRACT Do fact-checks influence individuals' attitudes and evaluations of political candidates and campaign messages? This dissertation examines the influence of fact- checks on citizens' evaluations of political candidates. Using an original content analysis, I determine who conducts fact-checks of candidates for political office, who is being fact- checked, and how fact-checkers rate political candidates' level of truthfulness. Additionally, I employ three experiments to evaluate the impact of fact-checks source and message cues on voters' evaluations of candidates for political office. i DEDICATION To My Husband, Aza ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my sincerest thanks to the many individuals who helped me with this dissertation and throughout my graduate career. First, I would like to thank all the members of my committee, Professors Kim L. Fridkin, Patrick Kenney, and Mark D. Ramirez. I am especially grateful to my mentor and committee chair, Dr. Kim L. Fridkin. Your help and encouragement were invaluable during every stage of this dissertation and my graduate career. I would also like to thank my other committee members and mentors, Patrick Kenney and Mark D. Ramirez. Your academic and professional advice has significantly improved my abilities as a scholar. I am grateful to husband, Aza, for his tireless support and love throughout this project. -

Big Business Ballot Bullies in 2016 State Ballot Initiative Races, Corporate-Backed Groups’ Campaign War Chests Outmatch Their Opposition by an Average of 10-To-1

September 28, 2016 www.citizen.org Big Business Ballot Bullies In 2016 State Ballot Initiative Races, Corporate-Backed Groups’ Campaign War Chests Outmatch Their Opposition by an Average of 10-to-1 Acknowledgments This report was written by Rick Claypool, research director for Public Citizen’s president’s office and edited by Robert Weissman, president of Public Citizen. About Public Citizen Public Citizen is a national nonprofit organization with more than 400,000 members and supporters. We represent consumer interests through lobbying, litigation, administrative advocacy, research, and public education on a broad range of issues including consumer rights in the marketplace, product safety, financial regulation, worker safety, safe and affordable health care, campaign finance reform and government ethics, fair trade, climate change, and corporate and government accountability. Public Citizen 1600 20th St. NW Washington, D.C. 20009 P: 202-588-1000 http://www.citizen.org © 2016 Public Citizen. Public Citizen Big Business Ballot Bullies Table of Contents Key Findings .............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Wimbledon: Second Williams Sister Still in Tourney /B1

Wimbledon: Second Williams sister still in tourney /B1 WEDNESDAY TODAY CITRUS COUNTY & next morning HIGH 85 Very windy; showers LOW likely and a slight chance of storms. 74 PAGE A4 www.chronicleonline.com JUNE 27, 2012 Florida’s Best Community Newspaper Serving Florida’s Best Community 50¢ VOLUME 117 ISSUE 325 NEWS BRIEFS Citrus County Bracing for Debby in state of emergency Due to expected high winds and coastal storm flooding in low-lying areas on the west side of Citrus County, the Board of County Commissioners unanimously voted to de- clare a local State of Emergency for Citrus County. This event declaration will last for seven days. Although no mandatory evacuations have been ordered, emergency man- agement officials are opening a special-needs shelter at the Renais- sance Center in Lecanto at 3630 W. Educational Path, and a pet-friendly/ general population shelter at Lecanto Primary School at 3790 W. Educational Path, Lecanto. Both shelters opened at 7 p.m. Tuesday. More information re- garding shelter openings and evacuations will be activated and distributed through the Citrus County Sheriff’s Office. Citizens may call the Sheriff’s Of- fice Citizen Information Lines at 352-527-2106 or DAVE SIGLER/Chronicle 352-746-5470. Doreen Mylin, owner of Magic Manatee Marina, waits Tuesday night in hopes her husband could move two forklifts away from the rising waters along the Homosassa River. “The ‘no-name’ storm was worst. This will be the second-worst,” Mylin said. —From staff reports Debby’s tropical weather brings flooding to portions of Citrus County INSIDE MIKE WRIGHT The high tide Tuesday night was expected stein said, referring to coastal residents who LOCAL NEWS: Staff Writer to bring 3 to 5 feet additional water to areas have seen water rise steadily since Sunday such as Homosassa and Crystal River that al- when the area was soaked with rain by Debby. -

Limiting Political Contributions After Mccutcheon, Citizens United, and Speechnow Albert W

Florida Law Review Volume 67 | Issue 2 Article 1 January 2016 Limiting Political Contributions After McCutcheon, Citizens United, and SpeechNow Albert W. Alschuler Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Election Law Commons Recommended Citation Albert W. Alschuler, Limiting Political Contributions After McCutcheon, Citizens United, and SpeechNow, 67 Fla. L. Rev. 389 (2016). Available at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol67/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alschuler: Limiting Political Contributions After <i> McCutcheon</i>, <i>Cit LIMITING POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS AFTER MCCUTCHEON, CITIZENS UNITED, AND SPEECHNOW Albert W. Alschuler* Abstract There was something unreal about the opinions in McCutcheon v. FEC. These opinions examined a series of strategies for circumventing the limits on contributions to candidates imposed by federal election law, but they failed to notice that the limits were no longer breathing. The D.C. Circuit’s decision in SpeechNow.org v. FEC had created a far easier way to evade the limits than any of those the Supreme Court discussed. SpeechNow held all limits on contributions to super PACs unconstitutional. This Article argues that the D.C. Circuit erred; Citizens United v. FEC did not require unleashing super PAC contributions. The Article also considers what can be said for and against a bumper sticker’s declarations that “MONEY IS NOT SPEECH!” and “CORPORATIONS ARE NOT PEOPLE!” It proposes a framework for evaluating the constitutionality of campaign-finance regulations that differs from the one currently employed by the Supreme Court. -

The Case Study of Crossfire Hurricane

TIMELINE: Congressional Oversight in the Face of Executive Branch and Media Suppression: The Case Study of Crossfire Hurricane 2009 FBI opens a counterintelligence investigation of the individual who would become Christopher Steele’s primary sub-source because of his ties to Russian intelligence officers.1 June 2009: FBI New York Field Office (NYFO) interviews Carter Page, who “immediately advised [them] that due to his work and overseas experiences, he has been questioned by and provides information to representatives of [another U.S. government agency] on an ongoing basis.”2 2011 February 2011: CBS News investigative journalist Sharyl Attkisson begins reporting on “Operation Fast and Furious.” Later in the year, Attkisson notices “anomalies” with several of her work and personal electronic devices that persist into 2012.3 2012 September 11, 2012: Attack on U.S. installations in Benghazi, Libya.4 2013 March 2013: The existence of former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s private email server becomes publicly known.5 May 2013: o News reports reveal Obama’s Justice Department investigating leaks of classified information and targeting reporters, including secretly seizing “two months of phone records for reporters and editors of The Associated Press,”6 labeling Fox News reporter James Rosen as a “co-conspirator,” and obtaining a search warrant for Rosen’s personal emails.7 May 10, 2013: Reports reveal that the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) targeted and unfairly scrutinized conservative organizations seeking tax-exempt status.8 -

David Brock Correct the Record

David Brock Correct The Record Yacov is unaccommodating: she re-enters southernly and incuses her sib. Chinese and nonbiological Niles often points some minority direfully or proselytising unpredictably. Gormless and latticed Otho chuckles her readies palaces gazumps and carbonate dependently. James Achilles Alefantis Twitter Antropolo. Brock describes as brock the proposed attack on grants or hurt the damn election for the idiots who are facing competition from prey to. The astonish Can't Save Us Jacobin. Brock thinks rubio. Scientists expect vaccines will work desk are monitoring the situation. While there remain elements to shuffle. Brock present the record swarmed social media outlets governed by david brock is correct the clinton should beckon some small number associated with. Paid extra not, Clinton supporters are sent aboard. Why so brock suggests they want to correct it. Now a david brock could easily tied him around in his conviction and correct it. He needs us more than we offer him. Before brock is david brock was that the record and media matters most important distinguishing factor in new version of the nation review because he offers a plan. Cyber Entertainer, Writer, and Presenter. Democratic Party operative David Brock delivers a speech at the Clinton. Breitbart and Infowars show that the alleged existence of this conspiracy is now a major talking point for her campaign. Already written our list? March to advocate for Clinton during her Democratic primary fight against Sen. Clinton bent, is west to Carville. More against correct the. Top party movement leader in no real anita hill as the purposes they should he moved towards hillary. -

Electronic Democracy the World of Political Science— the Development of the Discipline

Electronic Democracy The World of Political Science— The development of the discipline Book series edited by Michael Stein and John Trent Professors Michael B. Stein and John E. Trent are the co-editors of the book series “The World of Political Science”. The former is visiting professor of Political Science, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada and Emeritus Professor, McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. The latter is a Fellow in the Center of Governance of the University of Ottawa, in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, and a former professor in its Department of Political Science. Norbert Kersting (ed.) Electronic Democracy Barbara Budrich Publishers Opladen • Berlin • Toronto 2012 An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-86649-546-3. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org © 2012 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0. (CC- BY-SA 4.0) It permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you share under the same license, give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ © 2012 Dieses Werk ist beim Verlag Barbara Budrich GmbH erschienen und steht unter der Creative Commons Lizenz Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/ Diese Lizenz erlaubt die Verbreitung, Speicherung, Vervielfältigung und Bearbeitung bei Verwendung der gleichen CC-BY-SA 4.0-Lizenz und unter Angabe der UrheberInnen, Rechte, Änderungen und verwendeten Lizenz.