Super Pacs and 501(C) Groups in the 2016 Election

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

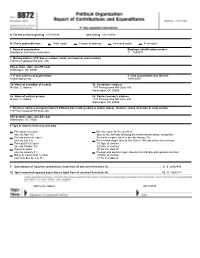

A for the Period Beginning 01/01/2014 and Ending 03/31/2014

A For the period beginning 01/01/2014 and ending 03/31/2014 B Check applicable box: ✔ Initial report Change of address Amended report Final report 1 Name of organization Employer identification number Republican Governors Association 11 - 3655877 2 Mailing address (P.O. box or number, street, and room or suite number) 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20006 3 E-mail address of organization: 4 Date organization was formed: [email protected] 10/04/2002 5a Name of custodian of records 5b Custodian's address Michael G. Adams 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 Washington, DC 20006 6a Name of contact person 6b Contact person's address Michael G. Adams 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 Washington, DC 20006 7 Business address of organization (if different from mailing address shown above). Number, street, and room or suite number 1747 Pennsylvania NW Suite 250 City or town, state, and ZIP code Washington, DC 20006 8 Type of report (check only one box) ✔ First quarterly report Monthly report for the month of: (due by April 15) (due by the 20th day following the month shown above, except the Second quarterly report December report, which is due by January 31) (due by July 15) Pre-election report (due by the 12th or 15th day before the election) Third quarterly report (1) Type of election: (due by October 15) (2) Date of election: Year-end report (3) For the state of: (due by January 31) Post-general election report (due by the 30th day after general election) Mid-year report (Non-election (1) Date of election: year only-due by July 31) (2) For the state of: 9 Total amount of reported contributions (total from all attached Schedules A) .......................................................................... -

An Analysis of Facebook Ads in European Election Campaigns

Are microtargeted campaign messages more negative and diverse? An analysis of Facebook ads in European election campaigns Alberto López Ortega University of Zurich Abstract Concerns about the use of online political microtargeting (OPM) by campaigners have arisen since Cambridge Analytica scandal hit the international political arena. In addition to providing conceptual clarity on OPM and explore the use of such technique in Europe, this paper seeks to empirically disentangle the differing behavior of campaigners when they message citizens through microtargeted rather than non-targeted campaigning. More precisely, I hypothesize that campaigners use negative campaigning and are more diverse in terms of topics when they use OPM. To investigate whether these expectations hold true, I use text-as-data techniques to analyze an original dataset of 4,091 political Facebook Ads during the last national elections in Austria, Italy, Germany and Sweden. Results show that while microtargeted ads might indeed be more thematically diverse, there does not seem to be a significant difference to non-microtargeted ads in terms of negativity. In conclusion, I discuss the implications of these findings for microtargeted campaigns and how future research could be conducted. Keywords: microtargeting, campaigns, negativity, topic diversity 1 1. Introduction In 2016, Alexander Nix, chief executive officer of Cambridge Analytica – a political consultancy firm – gave a presentation entitled “The Power of Big Data and Psychographics in the Electoral Process”. In his presentation, he explained how his firm allegedly turned Ted Cruz from being one of the less popular candidates in the Republican primaries to be the best competitor of Donald Trump. According to Nix’s words, they collected individuals’ personal data from a range of different sources, like land registries or online shopping data that allowed them to develop a psychographic profile of each citizen in the US. -

Federal Election Commission 1 2 First General Counsel's

MUR759900019 1 FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION 2 3 FIRST GENERAL COUNSEL’S REPORT 4 5 MUR 7304 6 DATE COMPLAINT FILED: December 15, 2017 7 DATE OF NOTIFICATIONS: December 21, 2017 8 DATE LAST RESPONSE RECEIVED September 4, 2018 9 DATE ACTIVATED: May 3, 2018 10 11 EARLIEST SOL: September 10, 2020 12 LATEST SOL: December 31, 2021 13 ELECTION CYCLE: 2016 14 15 COMPLAINANT: Committee to Defend the President 16 17 RESPONDENTS: Hillary Victory Fund and Elizabeth Jones in her official capacity as 18 treasurer 19 Hillary Rodham Clinton 20 Hillary for America and Elizabeth Jones in her official capacity as 21 treasurer 22 DNC Services Corporation/Democratic National Committee and 23 William Q. Derrough in his official capacity as treasurer 24 Alaska Democratic Party and Carolyn Covington in her official 25 capacity as treasurer 26 Democratic Party of Arkansas and Dawne Vandiver in her official 27 capacity as treasurer 28 Colorado Democratic Party and Rita Simas in her official capacity 29 as treasurer 30 Democratic State Committee (Delaware) and Helene Keeley in her 31 official capacity as treasurer 32 Democratic Executive Committee of Florida and Francesca Menes 33 in her official capacity as treasurer 34 Georgia Federal Elections Committee and Kip Carr in his official 35 capacity as treasurer 36 Idaho State Democratic Party and Leroy Hayes in his official 37 capacity as treasurer 38 Indiana Democratic Congressional Victory Committee and Henry 39 Fernandez in his official capacity as treasurer 40 Iowa Democratic Party and Ken Sagar in his official capacity as 41 treasurer 42 Kansas Democratic Party and Bill Hutton in his official capacity as 43 treasurer 44 Kentucky State Democratic Central Executive Committee and M. -

Brief of United States Senatorsenatorssss Sheldon Whitehouse and John Mccain As Amici Curiae in Support of Respondents ______

No. 11-1179 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States _______________ AMERICAN TRADITION PARTNERSHIP , INC ., F.K.A. WESTERN TRADITION PARTNERSHIP , INC ., ET AL ., Petitioners, v. STEVE BULLOCK , ATTORNEY GENERAL OF MONTANA , ET AL ., Respondents . _______________ On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The Supreme Court of Montana _______________ BRIEF OF UNITED STATES SENATORSENATORSSSS SHELDON WHITEHOUSE AND JOHN MCCAIN AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS _______________ NEAL KUMAR KATYAL Counsel of Record JUDITH E. COLEMAN HOGAN LOVELLS US LLP 555 Thirteenth Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20004 (202) 637-5528 [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................... ii STATEMENT OF INTEREST .................................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..................................... 2 ARGUMENT ............................................................... 3 I. THE MONTANA SUPREME COURT APPLIED THE CORRECT LEGAL STANDARD TO THE FACTUAL RECORD BEFORE IT. ........................................................... 3 II. THE COURT SHOULD IN ALL EVENTS DECLINE PETITIONERS’ INVITATION TO SUMMARILY REVERSE. ............................... 5 A. Political Spending After Citizens United Demonstrates that Coordination and Disclosure Rules Do Not Impose a Meaningful Check on the System. ................... 8 B. Unlimited, Coordinated and Undisclosed Spending Creates a Strong Potential for Quid Pro Quo Corruption. ........ 17 C. The Appearance of Corruption -

The Impact of Organizational Characteristics on Super PAC

The Impact of Organizational Characteristics on Super PAC Financing and Independent Expenditures Paul S. Herrnson University of Connecticut [email protected] Presented at the Meeting of the Campaign Finance Task Force, Bipartisan Policy Center, Washington, DC, April 21, 2017 (revised June 2017). 1 Exe cutive Summa ry Super PACs have grown in number, wealth, and influence since the Supreme Court laid the foundation for their formation in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, and the decisions reached by other courts and the FEC clarified the boundaries of their political participation. Their objectives and activities also have evolved. Super PACs are not nearly as monolithic as they have been portrayed by the media. While it is inaccurate to characterize them as representative of American society, it is important to recognize that they vary in wealth, mission, structure, affiliation, political perspective, financial transparency, and how and where they participate in political campaigns. Organizational characteristics influence super PAC financing, including the sums they raise. Organizational characteristics also affect super PAC independent expenditures, including the amounts spent, the elections in which they are made, the candidates targeted, and the tone of the messages delivered. The super PAC community is not static. It is likely to continue to evolve in response to legal challenges; regulatory decisions; the objectives of those who create, administer, and finance them; and changes in the broader political environment. 2 Contents I. Introduction 3 II. Data and Methods 4 III. Emergence and Development 7 IV. Organizational Characteristics 11 A. Finances 11 B. Mission 14 C. Affiliation 17 D. Financial Transparency 19 E. -

The Rise and Impact of Fact-Checking in U.S. Campaigns by Amanda Wintersieck a Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment O

The Rise and Impact of Fact-Checking in U.S. Campaigns by Amanda Wintersieck A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved April 2015 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Kim Fridkin, Chair Mark Ramirez Patrick Kenney ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2015 ABSTRACT Do fact-checks influence individuals' attitudes and evaluations of political candidates and campaign messages? This dissertation examines the influence of fact- checks on citizens' evaluations of political candidates. Using an original content analysis, I determine who conducts fact-checks of candidates for political office, who is being fact- checked, and how fact-checkers rate political candidates' level of truthfulness. Additionally, I employ three experiments to evaluate the impact of fact-checks source and message cues on voters' evaluations of candidates for political office. i DEDICATION To My Husband, Aza ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my sincerest thanks to the many individuals who helped me with this dissertation and throughout my graduate career. First, I would like to thank all the members of my committee, Professors Kim L. Fridkin, Patrick Kenney, and Mark D. Ramirez. I am especially grateful to my mentor and committee chair, Dr. Kim L. Fridkin. Your help and encouragement were invaluable during every stage of this dissertation and my graduate career. I would also like to thank my other committee members and mentors, Patrick Kenney and Mark D. Ramirez. Your academic and professional advice has significantly improved my abilities as a scholar. I am grateful to husband, Aza, for his tireless support and love throughout this project. -

The Civil War in the American Ruling Class

tripleC 16(2): 857-881, 2018 http://www.triple-c.at The Civil War in the American Ruling Class Scott Timcke Department of Literary, Cultural and Communication Studies, The University of The West Indies, St. Augustine, Trinidad and Tobago, [email protected] Abstract: American politics is at a decisive historical conjuncture, one that resembles Gramsci’s description of a Caesarian response to an organic crisis. The courts, as a lagging indicator, reveal this longstanding catastrophic equilibrium. Following an examination of class struggle ‘from above’, in this paper I trace how digital media instruments are used by different factions within the capitalist ruling class to capture and maintain the commanding heights of the American social structure. Using this hegemony, I argue that one can see the prospect of American Caesarism being institutionally entrenched via judicial appointments at the Supreme Court of the United States and other circuit courts. Keywords: Gramsci, Caesarism, ruling class, United States, hegemony Acknowledgement: Thanks are due to Rick Gruneau, Mariana Jarkova, Dylan Kerrigan, and Mark Smith for comments on an earlier draft. Thanks also go to the anonymous reviewers – the work has greatly improved because of their contributions. A version of this article was presented at the Local Entanglements of Global Inequalities conference, held at The University of The West Indies, St. Augustine in April 2018. 1. Introduction American politics is at a decisive historical juncture. Stalwarts in both the Democratic and the Republican Parties foresee the end of both parties. “I’m worried that I will be the last Republican president”, George W. Bush said as he recoiled at the actions of the Trump Administration (quoted in Baker 2017). -

Coalition Letter

Monday, April 15th 2019 Dear Members of Congress: On behalf of our organizations and the millions of American individuals, families, and business owners they represent, we urge you to focus on comprehensive reforms to prioritize, streamline and innovate the fnancing and regulation of our nation’s infrastructure projects rather than considering any increases to the federal gas tax. As part of any potential infrastructure package, Congress has an opportunity this year to institute major reforms to our federal funding and regulatory systems. Reforms are badly needed to improve outcomes, target spending toward critical projects, and streamline much needed maintenance and construction projects. Te goal this year should be a more modern and efcient national infrastructure system that will allow people and goods to move where they need to both safely and economically, contributing to an efective and well-functioning system of free enterprise. A 25-cent per gallon increase in the federal gas tax, a current proposal from some on and of Capitol Hill, would more than double the current rate and would amount to an estimated $394 billion tax increase over the next ten years. Before asking Americans for more of their hard earned money at the gas pump, lawmakers must consider how federal gas tax dollars are currently mishandled. More than 28 percent of funds from the Highway Trust Fund are currently diverted away from roads and bridges. Still more taxpayer dollars are wasted on infated costs due to outdated regulatory burdens, a complex and sluggish permitting system, and overly restrictive labor requirements. Tese reforms can be achieved by focusing on three core outcomes: 1) spending smarter on projects of true national priority, 2) reforming outdated and costly regulations, and 3) protecting Americans from new or increased tax burdens. -

Limiting Political Contributions After Mccutcheon, Citizens United, and Speechnow Albert W

Florida Law Review Volume 67 | Issue 2 Article 1 January 2016 Limiting Political Contributions After McCutcheon, Citizens United, and SpeechNow Albert W. Alschuler Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Election Law Commons Recommended Citation Albert W. Alschuler, Limiting Political Contributions After McCutcheon, Citizens United, and SpeechNow, 67 Fla. L. Rev. 389 (2016). Available at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol67/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alschuler: Limiting Political Contributions After <i> McCutcheon</i>, <i>Cit LIMITING POLITICAL CONTRIBUTIONS AFTER MCCUTCHEON, CITIZENS UNITED, AND SPEECHNOW Albert W. Alschuler* Abstract There was something unreal about the opinions in McCutcheon v. FEC. These opinions examined a series of strategies for circumventing the limits on contributions to candidates imposed by federal election law, but they failed to notice that the limits were no longer breathing. The D.C. Circuit’s decision in SpeechNow.org v. FEC had created a far easier way to evade the limits than any of those the Supreme Court discussed. SpeechNow held all limits on contributions to super PACs unconstitutional. This Article argues that the D.C. Circuit erred; Citizens United v. FEC did not require unleashing super PAC contributions. The Article also considers what can be said for and against a bumper sticker’s declarations that “MONEY IS NOT SPEECH!” and “CORPORATIONS ARE NOT PEOPLE!” It proposes a framework for evaluating the constitutionality of campaign-finance regulations that differs from the one currently employed by the Supreme Court. -

Marc Short Chief of Staff, Vice President Pence

MARC SHORT CHIEF OF STAFF, VICE PRESIDENT PENCE u Life in Brief Quick Summary Hometown: Virginia Beach, VA Lifelong conservative GOP operative who rose through party ranks to become a trusted Mike Current Residence: Arlington, VA Pence confidante. Utilizes expansive network of Koch allies, White House staff, and congressional Education ties to push Administration priorities • BA, Washington & Lee, 1992 • MBA, University of Virginia, 2004 • Polished and pragmatic tactician who plays a behind-the-scenes role advising Vice President Family: Pence and other senior leaders • Married to Kristen Short, who has • Early conservative political views shaped By his worked for Young America’s Foundation, father, Dick Short, a wealthy GOP donor well- Freedom Alliance, and the Charles G. connected to Virginia GOP circles Koch Foundation • Extensive experience with Freedom Partners and • Three school-aged children the Koch Brothers exposed him to large network of GOP donors and influencers Work History • Earned reputation as smart strategist on the Hill • Chief of Staff to the Vice President of the working closely with then-Rep. Mike Pence United States, 2019-Present • Provided GOP estaBlishment credentials and • Senior Fellow at UVA Miller Center of congressional experience to Trump White House PuBlic Affairs, 2018-19 to advance Administration’s early agenda, • Contributor for CNN, 2018-19 including on 2017 tax cuts and Neil Gorsuch’s • Partner at Guidepost Strategies, 2018-19 confirmation to the Supreme Court • White House Director of Legislative • -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Packaging Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3th639mx Author Galloway, Catherine Suzanne Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California PACKAGING POLITICS by Catherine Suzanne Galloway A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California at Berkeley Committee in charge Professor Jack Citrin, Chair Professor Eric Schickler Professor Taeku Lee Professor Tom Goldstein Fall 2012 Abstract Packaging Politics by Catherine Suzanne Galloway Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor Jack Citrin, Chair The United States, with its early consumerist orientation, has a lengthy history of drawing on similar techniques to influence popular opinion about political issues and candidates as are used by businesses to market their wares to consumers. Packaging Politics looks at how the rise of consumer culture over the past 60 years has influenced presidential campaigning and political culture more broadly. Drawing on interviews with political consultants, political reporters, marketing experts and communications scholars, Packaging Politics explores the formal and informal ways that commercial marketing methods – specifically emotional and open source branding and micro and behavioral targeting – have migrated to the -

Party Foul: Inside the Rise of Spies, Mercenaries, and Billionaire Moneymen -- Printout -- TIME

Party Foul: Inside the Rise of Spies, Mercenaries, and Billionaire Moneymen -- Printout -- TIME Back to Article Click to Print Monday, Mar. 03, 2014 Party Foul: Inside the Rise of Spies, Mercenaries, and Billionaire Moneymen By Alex Altman; Zeke Miller On a cold Saturday in January, a spy slipped into a craft brewery in downtown Des Moines, Iowa, where Hillary Clinton's standing army was huddled in a private room. The 43-year-old operative lurked in the corner with a camera on a tripod, recording the group of old Clinton hands as they plotted her path to the presidency. "Nobody," veteran Democratic strategist Craig Smith told the group, "had ever done it like this before." Within hours, a clip of the gathering was shipped to the snoop's employer, a for-profit research firm in northern Virginia. From there, it was packaged for a conservative magazine and subsequently went viral online. It was an early score in a presidential election that won't officially begin for another year--and it happened without any involvement from a candidate or either party. The Clintonites were members of Ready for Hillary, a super PAC that is spending millions of dollars to assemble a grassroots battalion for the former Secretary of State's campaign-in-waiting. And the infiltrator was one of more than two dozen "trackers" dispatched across 19 states by a company looking to damage Democrats. This is the dawn of the outsourced campaign. For decades, elections have been the business of candidates and political parties and the professionals they employed. People with names on the ballot bought their own ads and wielded the ability to smite enemies with a single phone call.