Solubility of Solids in Dense Gases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ideal-Gas Mixtures and Real-Gas Mixtures

Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach, 6th Edition Yunus A. Cengel, Michael A. Boles McGraw-Hill, 2008 Chapter 13 GAS MIXTURES Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Objectives • Develop rules for determining nonreacting gas mixture properties from knowledge of mixture composition and the properties of the individual components. • Define the quantities used to describe the composition of a mixture, such as mass fraction, mole fraction, and volume fraction. • Apply the rules for determining mixture properties to ideal-gas mixtures and real-gas mixtures. • Predict the P-v-T behavior of gas mixtures based on Dalton’s law of additive pressures and Amagat’s law of additive volumes. • Perform energy and exergy analysis of mixing processes. 2 COMPOSITION OF A GAS MIXTURE: MASS AND MOLE FRACTIONS To determine the properties of a mixture, we need to know the composition of the mixture as well as the properties of the individual components. There are two ways to describe the composition of a mixture: Molar analysis: specifying the number of moles of each component Gravimetric analysis: specifying the mass of each component The mass of a mixture is equal to the sum of the masses of its components. Mass fraction Mole The number of moles of a nonreacting mixture fraction is equal to the sum of the number of moles of its components. 3 Apparent (or average) molar mass The sum of the mass and mole fractions of a mixture is equal to 1. Gas constant The molar mass of a mixture Mass and mole fractions of a mixture are related by The sum of the mole fractions of a mixture is equal to 1. -

An Empirical Model Predicting the Viscosity of Highly Concentrated

Rheol Acta &2001) 40: 434±440 Ó Springer-Verlag 2001 ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Burkhardt Dames An empirical model predicting the viscosity Bradley Ron Morrison Norbert Willenbacher of highly concentrated, bimodal dispersions with colloidal interactions Abstract The relationship between the particles. Starting from a limiting Received: 7 June 2000 Accepted: 12 February 2001 particle size distribution and viscos- value of 2 for non-interacting either ity of concentrated dispersions is of colloidal or non-colloidal particles, great industrial importance, since it e generally increases strongly with is the key to get high solids disper- decreasing particle size. For a given sions or suspensions. The problem is particle system it then can be treated here experimentally as well expressed as a function of the num- as theoretically for the special case ber average particle diameter. As a of strongly interacting colloidal consequence, the viscosity of bimo- particles. An empirical model based dal dispersions varies not only with on a generalized Quemada equation the size ratio of large to small ~ / Àe g g 1 À / is used to describe particles, but also depends on the g as a functionmax of volume fraction absolute particle size going through for mono- as well as multimodal a minimum as the size ratio increas- dispersions. The pre-factor g~ ac- es. Furthermore, the well-known counts for the shear rate dependence viscosity minimum for bimodal dis- of g and does not aect the shape of persions with volumetric mixing the g vs / curves. It is shown here ratios of around 30/70 of small to for the ®rst time that colloidal large particles is shown to vanish if interactions do not show up in the colloidal interactions contribute maximum packing parameter and signi®cantly. -

Colloidal Suspensions

Chapter 9 Colloidal suspensions 9.1 Introduction So far we have discussed the motion of one single Brownian particle in a surrounding fluid and eventually in an extaernal potential. There are many practical applications of colloidal suspensions where several interacting Brownian particles are dissolved in a fluid. Colloid science has a long history startying with the observations by Robert Brown in 1828. The colloidal state was identified by Thomas Graham in 1861. In the first decade of last century studies of colloids played a central role in the development of statistical physics. The experiments of Perrin 1910, combined with Einstein's theory of Brownian motion from 1905, not only provided a determination of Avogadro's number but also laid to rest remaining doubts about the molecular composition of matter. An important event in the development of a quantitative description of colloidal systems was the derivation of effective pair potentials of charged colloidal particles. Much subsequent work, largely in the domain of chemistry, dealt with the stability of charged colloids and their aggregation under the influence of van der Waals attractions when the Coulombic repulsion is screened strongly by the addition of electrolyte. Synthetic colloidal spheres were first made in the 1940's. In the last twenty years the availability of several such reasonably well characterised "model" colloidal systems has attracted physicists to the field once more. The study, both theoretical and experimental, of the structure and dynamics of colloidal suspensions is now a vigorous and growing subject which spans chemistry, chemical engineering and physics. A colloidal dispersion is a heterogeneous system in which particles of solid or droplets of liquid are dispersed in a liquid medium. -

Lecture 3. the Basic Properties of the Natural Atmosphere 1. Composition

Lecture 3. The basic properties of the natural atmosphere Objectives: 1. Composition of air. 2. Pressure. 3. Temperature. 4. Density. 5. Concentration. Mole. Mixing ratio. 6. Gas laws. 7. Dry air and moist air. Readings: Turco: p.11-27, 38-43, 366-367, 490-492; Brimblecombe: p. 1-5 1. Composition of air. The word atmosphere derives from the Greek atmo (vapor) and spherios (sphere). The Earth’s atmosphere is a mixture of gases that we call air. Air usually contains a number of small particles (atmospheric aerosols), clouds of condensed water, and ice cloud. NOTE : The atmosphere is a thin veil of gases; if our planet were the size of an apple, its atmosphere would be thick as the apple peel. Some 80% of the mass of the atmosphere is within 10 km of the surface of the Earth, which has a diameter of about 12,742 km. The Earth’s atmosphere as a mixture of gases is characterized by pressure, temperature, and density which vary with altitude (will be discussed in Lecture 4). The atmosphere below about 100 km is called Homosphere. This part of the atmosphere consists of uniform mixtures of gases as illustrated in Table 3.1. 1 Table 3.1. The composition of air. Gases Fraction of air Constant gases Nitrogen, N2 78.08% Oxygen, O2 20.95% Argon, Ar 0.93% Neon, Ne 0.0018% Helium, He 0.0005% Krypton, Kr 0.00011% Xenon, Xe 0.000009% Variable gases Water vapor, H2O 4.0% (maximum, in the tropics) 0.00001% (minimum, at the South Pole) Carbon dioxide, CO2 0.0365% (increasing ~0.4% per year) Methane, CH4 ~0.00018% (increases due to agriculture) Hydrogen, H2 ~0.00006% Nitrous oxide, N2O ~0.00003% Carbon monoxide, CO ~0.000009% Ozone, O3 ~0.000001% - 0.0004% Fluorocarbon 12, CF2Cl2 ~0.00000005% Other gases 1% Oxygen 21% Nitrogen 78% 2 • Some gases in Table 3.1 are called constant gases because the ratio of the number of molecules for each gas and the total number of molecules of air do not change substantially from time to time or place to place. -

Gp-Cpc-01 Units – Composition – Basic Ideas

GP-CPC-01 UNITS – BASIC IDEAS – COMPOSITION 11-06-2020 Prof.G.Prabhakar Chem Engg, SVU GP-CPC-01 UNITS – CONVERSION (1) ➢ A two term system is followed. A base unit is chosen and the number of base units that represent the quantity is added ahead of the base unit. Number Base unit Eg : 2 kg, 4 meters , 60 seconds ➢ Manipulations Possible : • If the nature & base unit are the same, direct addition / subtraction is permitted 2 m + 4 m = 6m ; 5 kg – 2.5 kg = 2.5 kg • If the nature is the same but the base unit is different , say, 1 m + 10 c m both m and the cm are length units but do not represent identical quantity, Equivalence considered 2 options are available. 1 m is equivalent to 100 cm So, 100 cm + 10 cm = 110 cm 0.01 m is equivalent to 1 cm 1 m + 10 (0.01) m = 1. 1 m • If the nature of the quantity is different, addition / subtraction is NOT possible. Factors used to check equivalence are known as Conversion Factors. GP-CPC-01 UNITS – CONVERSION (2) • For multiplication / division, there are no such restrictions. They give rise to a set called derived units Even if there is divergence in the nature, multiplication / division can be carried out. Eg : Velocity ( length divided by time ) Mass flow rate (Mass divided by time) Mass Flux ( Mass divided by area (Length 2) – time). Force (Mass * Acceleration = Mass * Length / time 2) In derived units, each unit is to be individually converted to suit the requirement Density = 500 kg / m3 . -

Solutions Mole Fraction of Component a = Xa Mass Fraction of Component a = Ma Volume Fraction of Component a = Φa Typically We

Solutions Mole fraction of component A = xA Mass Fraction of component A = mA Volume Fraction of component A = fA Typically we make a binary blend, A + B, with mass fraction, m A, and want volume fraction, fA, or mole fraction , xA. fA = (mA/rA)/((mA/rA) + (m B/rB)) xA = (mA/MWA)/((mA/MWA) + (m B/MWB)) 1 Solutions Three ways to get entropy and free energy of mixing A) Isothermal free energy expression, pressure expression B) Isothermal volume expansion approach, volume expression C) From statistical thermodynamics 2 Mix two ideal gasses, A and B p = pA + pB pA is the partial pressure pA = xAp For single component molar G = µ µ 0 is at p0,A = 1 bar At pressure pA for a pure component µ A = µ0,A + RT ln(p/p0,A) = µ0,A + RT ln(p) For a mixture of A and B with a total pressure ptot = p0,A = 1 bar and pA = xA ptot For component A in a binary mixture µ A(xA) = µ0.A + RT xAln (xA ptot/p0,A) = µ0.A + xART ln (xA) Notice that xA must be less than or equal to 1, so ln xA must be negative or 0 So the chemical potential has to drop in the solution for a solution to exist. Ideal gasses only have entropy so entropy drives mixing in this case. This can be written, xA = exp((µ A(xA) - µ 0.A)/RT) Which indicates that xA is the Boltzmann probability of finding A 3 Mix two real gasses, A and B µ A* = µ 0.A if p = 1 4 Ideal Gas Mixing For isothermal DU = CV dT = 0 Q = W = -pdV For ideal gas Q = W = nRTln(V f/Vi) Q = DS/T DS = nRln(V f/Vi) Consider a process of expansion of a gas from VA to V tot The change in entropy is DSA = nARln(V tot/VA) = - nARln(VA/V tot) Consider an isochoric mixing process of ideal gasses A and B. -

Calculation of Steam Volume Fraction in Subcooled Boiling

AE-28G UDC 535.248.2 CD 00 CN UJ < Calculation of Steam Volume Fraction in Subcooled Boiling S. Z. Rouhani AKTIEBOLAGET ATOMENERGI STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN 1967 AE -286 CALCULATION OF STEAM VOLUME FRACTION IN SUBCOOLED BOILING by S. Z . Rouhani SUMMARY An analysis of subcooled boiling is presented. It is assumed that he at is removed by vapor generation, heating of the liquid that replaces the detached bubbles, and to some extent by single phase heat transfer. Two regions of subcooled boiling are considered and a criterion is provided for obtaining the limiting value of subcooling between the two regions. Condensation of vapor in the subcooled liquid is analysed and the relative velocity of vapor with respect to the liquid is neglected in these regions. The theoretical arguments result in some equations for the calculation of steam volume frac tion and true liquid subcooling. Printed and distributed in June 1 967. LIST OF CONTENTS Page Introduction 3 Literature Survey 3 Theory 4 Assumptions and the Derivation of the Basic Equations 4 Remarks on the Liquid Subcooling 6 The integrated Equation of Subcooled Void 7 Estimation of the Rate of Bubble Condensation 9 Effects of Void and Channel Geometry on cp and cp^ 1 0 Effect of Subcooling on cp^ and cp^ 1 0 Effects of Mass Velocity, Heat Flux, and Physical Properties on cpj and cp,, 12 The Limiting Value of Subcooling in the First Region 1 3 Resume of Calculation Procedure 14 Calculations of a in the First Region 14 Calculation of O' in the Second Region 1 4 Steam Quality in Subcooled Boiling 1 5 Comparison with Experimental Data 1 5 Conclusion 15 Nomenclature 18 Greek Letters 20 References 22 Figure Captions 23 - 3 - INTRODUCTION The intensity of subcooled boiling depends on many factors, among which the degree of subcooling, surface heat flux, mass veloc ity, and physical properties of the liquid and its vapor. -

Greek Letters

Seader_44460_fm.qxd 8/30/05 5:15 PM Page xxvi xxvi Nomenclature Xm mole fraction of functional group m in y mole fraction in vapor phase; distance; mass UNIFAC method fraction in extract; mass fraction in overflow x mole fraction in liquid phase; mole fraction in y vector of mole fractions in vapor phase any phase; distance; mass fraction in raffinate; Z compressibility factor = Pv/RT; total mass; mass fraction in underflow; mass fraction of height particles Z froth height on a tray C f = / x normalized mole fraction xi xj 1 ZL length of liquid flow path across a tray j=1 Z¯ lattice coordination number in UNIQUAC and x vector of mole fractions in liquid phase UNIFAC equations xn fraction of crystals of size smaller than L z mole fraction in any phase; overall mole frac- Y mole or mass ratio; mass ratio of soluble mate- tion in combined phases; distance; overall mole rial to solvent in overflow; pressure-drop fraction in feed; dimensionless crystal size; factor for packed columns defined by (6-102); length of liquid flow path across tray concentration of solute in solvent; parameter z vector of mole fractions in overall mixture in (9-34) Greek Letters ␣ thermal diffusivity, k/CP ; relative volatility; ij binary interaction parameter in Wilson equation surface area per adsorbed molecule mV/L; radiation wavelength ␣∗ ideal separation factor for a membrane +, − limiting ionic conductances of cation and ␣ij relative volatility of component i with respect anion, respectively to component j for vapor-liquid equilibria; ij energy of interaction -

Measurement of Particle Number Density and Volume Fraction in A

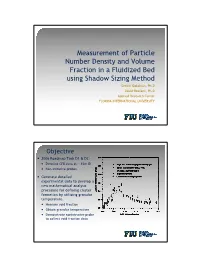

Measurement of Particle Number Density and Volume Fraction in a Fluidized Bed using Shadow Sizing Method Seckin Gokaltun, Ph.D David Roelant, Ph.D Applied Research Center FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Objective y 2006 Roadmap Task D1 & D2: y Detailed CFB data at ~.15m ID y Non-intrusive probes y Generate detailed experimental data to develop a new mathematical analysis procedure for defining cluster formation by utilizing granular temperature. y Measure void fraction y Obtain granular temperature y Demonstrate nonintrusive probe to collect void fraction data Granular Temperature Granular theory Kinetic theory y From the ideal gas law: y Assumptions: y Very large number of PV = NkBT particles (for valid statistical treatment) where kB is the Boltzmann y Distance among particles much larger than molecular constant and the absolute size temperature, thus: y Random particle motion with 2 constant speeds PV = NkBT = Nmvrms / 3 2 y Elastic particle-particle and T = mvrms / 3kB particle-walls collisions (no n loss of energy) v 2 = v 2 y Molecules obey Newton Laws rms ∑ i i =1 is the root-mean-square velocity Granular Temperature y From velocity 1 θ = ()σ 2 + σ 2 + σ 2 3 θ r z 2 2 where: σ z = ()u z − u y uz is particle velocity u is the average particle velocity y From voidage for dilute flows 2 3 θ ∝ ε s y From voidage for dense flows 2 θ ∝1 ε s 6 Glass beads imaged at FIU 2008 Volume Fraction y Solids volume fraction: nV ε = p s Ah y n : the number of particles y Vp : is the volume of single particle y A : the view area y h : the depth of view (Lecuona et al., Meas. -

Mole Fraction - Wikipedia

4/28/2020 Mole fraction - Wikipedia Mole fraction In chemistry, the mole fraction or molar fraction (xi) is defined as unit of the amount of a constituent (expressed in moles), ni divided by the total amount of all constituents in a mixture (also [1] expressed in moles), ntot: .These expression is given below:- The sum of all the mole fractions is equal to 1: The same concept expressed with a denominator of 100 is the mole percent or molar percentage or molar proportion (mol%). The mole fraction is also called the amount fraction.[1] It is identical to the number fraction, which is defined as the number of molecules of a constituent Ni divided by the total number of all molecules Ntot. The mole fraction is sometimes denoted by the lowercase Greek letter χ (chi) instead of a Roman x.[2][3] For mixtures of gases, IUPAC recommends the letter y.[1] The National Institute of Standards and Technology of the United States prefers the term amount-of- substance fraction over mole fraction because it does not contain the name of the unit mole.[4] Whereas mole fraction is a ratio of moles to moles, molar concentration is a quotient of moles to volume. The mole fraction is one way of expressing the composition of a mixture with a dimensionless quantity; mass fraction (percentage by weight, wt%) and volume fraction (percentage by volume, vol%) are others. Contents Properties Related quantities Mass fraction Molar mixing ratio Mixing binary mixtures with a common component to form ternary mixtures Mole percentage Mass concentration Molar concentration Mass and molar mass Spatial variation and gradient References https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mole_fraction 1/5 4/28/2020 Mole fraction - Wikipedia Properties Mole fraction is used very frequently in the construction of phase diagrams. -

Accuracy of Molar Solubility Prediction from Hansen Parameters. an Exemplified Treatment of the Bioantioxidant L-Ascorbic Acid

applied sciences Article Accuracy of Molar Solubility Prediction from Hansen Parameters. An Exemplified Treatment of the Bioantioxidant l-Ascorbic Acid Ralph J. Lehnert 1,2,* and Richard Schilling 2,3 1 School of Chemistry, Reutlingen University of Applied Sciences, 72762 Reutlingen, Germany 2 Reutlingen Research Institute, Reutlingen University of Applied Sciences, 72762 Reutlingen, Germany; [email protected] 3 Lehr- und Forschungszentrum für Prozessanalyse und Technologie (LFZ-PA&T), Reutlingen University of Applied Sciences, 72762 Reutlingen, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-7121-2712003 Received: 11 April 2020; Accepted: 17 June 2020; Published: 22 June 2020 Abstract: Estimating molar solubility from the Hildebrand-Scott relation employing Hansen solubility parameters (HSP) is widely presumed a valid semi-quantitative approach. To test this presumption and to determine quantitatively the inherent accuracy of such a solubility prognosis, l-ascorbic acid (LAA) was treated as an example of a commercially important solute. Analytical calculus and Monte Carlo (MC) simulation were performed for 20 common solvents with total HSP ranging from 14.5 to 33.0 (MPa)0.5 utilizing validated material data. It was found that, due to the uncertainty of the material data used in the calculations, the solubility prediction had a large scattering and, thus, a low precision. Prediction power is most adversely affected by the uncertainty of the HSP estimates (solvent and solute), followed by the solute heat of fusion. The solute melting temperature and molar volume have minor effects. Computed and experimental solubilities show the same qualitative behavior, while quantitative discrepancies reach one to three orders of magnitude. -

Characteristics of the Solid Volume Fraction Fluctuations in a CFB Sirpa Kallio VTT Et Chnical Research Centre of Finland, Finland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Engineering Conferences International Engineering Conferences International ECI Digital Archives 10th International Conference on Circulating Fluidized Beds and Fluidization Technology - Refereed Proceedings CFB-10 Spring 5-3-2011 Characteristics of the Solid Volume Fraction Fluctuations in a CFB Sirpa Kallio VTT eT chnical Research Centre of Finland, Finland Juho Peltola VTT eT chnical Research Centre of Finland, Finland Veikko Taivassalo VTT, Finland Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.engconfintl.org/cfb10 Part of the Chemical Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Sirpa Kallio, Juho Peltola, and Veikko Taivassalo, "Characteristics of the Solid Volume Fraction Fluctuations in a CFB" in "10th International Conference on Circulating Fluidized Beds and Fluidization Technology - CFB-10", T. Knowlton, PSRI Eds, ECI Symposium Series, (2013). http://dc.engconfintl.org/cfb10/63 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Refereed Proceedings at ECI Digital Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in 10th International Conference on Circulating Fluidized Beds and Fluidization Technology - CFB-10 by an authorized administrator of ECI Digital Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHARACTERISTICS OF THE SOLID VOLUME FRACTION FLUCTUATIONS IN A CFB Sirpa Kallio, Juho Peltola, Veikko Taivassalo VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland P.O.Box 1000, FI-02044 VTT, Finland ABSTRACT In the paper, the fluctuation characteristics of the solids volume fraction in a CFB are evaluated from measurements and Eulerian-Eulerian CFD simulations. In both cases, similarly large fluctuations are observed in the intermediate voidage range whereas dense and dilute suspension regions are more uniform, as expected.