Colloidal Suspensions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ideal-Gas Mixtures and Real-Gas Mixtures

Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach, 6th Edition Yunus A. Cengel, Michael A. Boles McGraw-Hill, 2008 Chapter 13 GAS MIXTURES Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Objectives • Develop rules for determining nonreacting gas mixture properties from knowledge of mixture composition and the properties of the individual components. • Define the quantities used to describe the composition of a mixture, such as mass fraction, mole fraction, and volume fraction. • Apply the rules for determining mixture properties to ideal-gas mixtures and real-gas mixtures. • Predict the P-v-T behavior of gas mixtures based on Dalton’s law of additive pressures and Amagat’s law of additive volumes. • Perform energy and exergy analysis of mixing processes. 2 COMPOSITION OF A GAS MIXTURE: MASS AND MOLE FRACTIONS To determine the properties of a mixture, we need to know the composition of the mixture as well as the properties of the individual components. There are two ways to describe the composition of a mixture: Molar analysis: specifying the number of moles of each component Gravimetric analysis: specifying the mass of each component The mass of a mixture is equal to the sum of the masses of its components. Mass fraction Mole The number of moles of a nonreacting mixture fraction is equal to the sum of the number of moles of its components. 3 Apparent (or average) molar mass The sum of the mass and mole fractions of a mixture is equal to 1. Gas constant The molar mass of a mixture Mass and mole fractions of a mixture are related by The sum of the mole fractions of a mixture is equal to 1. -

Development Team

Paper No: 16 Environmental Chemistry Module: 01 Environmental Concentration Units Development Team Prof. R.K. Kohli Principal Investigator & Prof. V.K. Garg & Prof. Ashok Dhawan Co- Principal Investigator Central University of Punjab, Bathinda Prof. K.S. Gupta Paper Coordinator University of Rajasthan, Jaipur Prof. K.S. Gupta Content Writer University of Rajasthan, Jaipur Content Reviewer Dr. V.K. Garg Central University of Punjab, Bathinda Anchor Institute Central University of Punjab 1 Environmental Chemistry Environmental Environmental Concentration Units Sciences Description of Module Subject Name Environmental Sciences Paper Name Environmental Chemistry Module Name/Title Environmental Concentration Units Module Id EVS/EC-XVI/01 Pre-requisites A basic knowledge of concentration units 1. To define exponents, prefixes and symbols based on SI units 2. To define molarity and molality 3. To define number density and mixing ratio 4. To define parts –per notation by volume Objectives 5. To define parts-per notation by mass by mass 6. To define mass by volume unit for trace gases in air 7. To define mass by volume unit for aqueous media 8. To convert one unit into another Keywords Environmental concentrations, parts- per notations, ppm, ppb, ppt, partial pressure 2 Environmental Chemistry Environmental Environmental Concentration Units Sciences Module 1: Environmental Concentration Units Contents 1. Introduction 2. Exponents 3. Environmental Concentration Units 4. Molarity, mol/L 5. Molality, mol/kg 6. Number Density (n) 7. Mixing Ratio 8. Parts-Per Notation by Volume 9. ppmv, ppbv and pptv 10. Parts-Per Notation by Mass by Mass. 11. Mass by Volume Unit for Trace Gases in Air: Microgram per Cubic Meter, µg/m3 12. -

Mechanical Dispersion of Clay from Soil Into Water: Readily-Dispersed and Spontaneously-Dispersed Clay Ewa A

Int. Agrophys., 2015, 29, 31-37 doi: 10.1515/intag-2015-0007 Mechanical dispersion of clay from soil into water: readily-dispersed and spontaneously-dispersed clay Ewa A. Czyż1,2* and Anthony R. Dexter2 1Department of Soil Science, Environmental Chemistry and Hydrology, University of Rzeszów, Zelwerowicza 8b, 35-601 Rzeszów, Poland 2Institute of Soil Science and Plant Cultivation (IUNG-PIB), Czartoryskich 8, 24-100 Puławy, Poland Received July 1, 2014; accepted October 10, 2014 A b s t r a c t. A method for the experimental determination of Clay particles can either flocculate or disperse in aque- the amount of clay dispersed from soil into water is described. The ous solution. When flocculation occurs, the particles com- method was evaluated using soil samples from agricultural fields bine to form larger, compound particles such as soil in 18 locations in Poland. Soil particle size distributions, contents microaggregates. When dispersion occurs, the particles of organic matter and exchangeable cations were measured by separate in suspension due to their electrical charge. Clay standard methods. Sub-samples were placed in distilled water flocculation leads to soils that are considered to be stable in wa- and were subjected to four different energy inputs obtained by ter whereas dispersion is associated with soils that are consi- different numbers of inversions (end-over-end movements). The dered to be unstable in water. We may note that this termi- amounts of clay that dispersed into suspension were measured by light scattering (turbidimetry). An empirical equation was devel- nology is the opposite of that used in colloid science where oped that provided an approximate fit to the experimental data for the terms ‘stable’ and ‘unstable’ are used in relation to the turbidity as a function of number of inversions. -

An Empirical Model Predicting the Viscosity of Highly Concentrated

Rheol Acta &2001) 40: 434±440 Ó Springer-Verlag 2001 ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Burkhardt Dames An empirical model predicting the viscosity Bradley Ron Morrison Norbert Willenbacher of highly concentrated, bimodal dispersions with colloidal interactions Abstract The relationship between the particles. Starting from a limiting Received: 7 June 2000 Accepted: 12 February 2001 particle size distribution and viscos- value of 2 for non-interacting either ity of concentrated dispersions is of colloidal or non-colloidal particles, great industrial importance, since it e generally increases strongly with is the key to get high solids disper- decreasing particle size. For a given sions or suspensions. The problem is particle system it then can be treated here experimentally as well expressed as a function of the num- as theoretically for the special case ber average particle diameter. As a of strongly interacting colloidal consequence, the viscosity of bimo- particles. An empirical model based dal dispersions varies not only with on a generalized Quemada equation the size ratio of large to small ~ / Àe g g 1 À / is used to describe particles, but also depends on the g as a functionmax of volume fraction absolute particle size going through for mono- as well as multimodal a minimum as the size ratio increas- dispersions. The pre-factor g~ ac- es. Furthermore, the well-known counts for the shear rate dependence viscosity minimum for bimodal dis- of g and does not aect the shape of persions with volumetric mixing the g vs / curves. It is shown here ratios of around 30/70 of small to for the ®rst time that colloidal large particles is shown to vanish if interactions do not show up in the colloidal interactions contribute maximum packing parameter and signi®cantly. -

Supplement Of

Supplement of Effects of Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation and Relative Humidity on the Heterogeneous OH Oxidation of Inorganic-Organic Aerosols: Insights from Methylglutaric Acid/Ammonium Sulfate Particles Hoi Ki Lam1, Rongshuang Xu1, Jack Choczynski2, James F. Davies2, Dongwan Ham3, Mijung Song3, Andreas Zuend4, Wentao Li5, Ying-Lung Steve Tse5, Man Nin Chan 1,6 1Earth System Science Programme, Faculty of Science, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China 2Department of Chemistry, University of California Riverside, Riverside, CA, USA 3Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Jeonbuk National University, Jeollabuk-do, Republic of Korea 4Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, McGill University, Montreal, Québec, Canada 5Departemnt of Chemistry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China’ 6The Institute of Environment, Energy and Sustainability, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China Corresponding author: [email protected] Table S1. Composition, viscosity, diffusion coefficient and mixing time scale of aqueous droplets containing 3-MGA and ammonium sulfate (AS) in an organic- to-inorganic dry mass ratio (OIR) = 1 at different RH predicted by the AIOMFAC-LLE. RH (%) 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 88 Salt-rich phase (Phase α) Mass fraction of 3-MGA 0.00132 0.00372 0.00904 0.0202 / / Mass fraction of AS 0.658 0.616 0.569 0.514 / / Mass fraction of H2O 0.341 0.380 0.422 0.466 / / Organic-rich phase (Phase β) Mass fraction of 3-MGA 0.612 0.596 0.574 0.546 / / Mass fraction of AS 0.218 0.209 0.199 0.190 -

Calculation Exercises with Answers and Solutions

Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Calculation Exercises Contents Exercise A, chapter 1 - 3 in Jacob …………………………………………………… 2 Exercise B, chapter 4, 6 in Jacob …………………………………………………… 6 Exercise C, chapter 7, 8 in Jacob, OH on aerosols and booklet by Heintzenberg … 11 Exercise D, chapter 9 in Jacob………………………………………………………. 16 Exercise E, chapter 10 in Jacob……………………………………………………… 20 Exercise F, chapter 11 - 13 in Jacob………………………………………………… 24 Answers and solutions …………………………………………………………………. 29 Note that approximately 40% of the written exam deals with calculations. The remainder is about understanding of the theory. Exercises marked with an asterisk (*) are for the most interested students. These exercises are more comprehensive and/or difficult than questions appearing in the written exam. 1 Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics – Exercise A, chap. 1 – 3 Recommended activity before exercise: Try to solve 1:1 – 1:5, 2:1 – 2:2 and 3:1 – 3:2. Summary: Concentration Example Advantage Number density No. molecules/m3, Useful for calculations of reaction kmol/m3 rates in the gas phase Partial pressure Useful measure on the amount of a substance that easily can be converted to mixing ratio Mixing ratio ppmv can mean e.g. Concentration relative to the mole/mole or partial concentration of air molecules. Very pressure/total pressure useful because air is compressible. Ideal gas law: PV = nRT Molar mass: M = m/n Density: ρ = m/V = PM/RT; (from the two equations above) Mixing ratio (vol): Cx = nx/na = Px/Pa ≠ mx/ma Number density: Cvol = nNav/V 26 -1 Avogadro’s -

Lecture 3. the Basic Properties of the Natural Atmosphere 1. Composition

Lecture 3. The basic properties of the natural atmosphere Objectives: 1. Composition of air. 2. Pressure. 3. Temperature. 4. Density. 5. Concentration. Mole. Mixing ratio. 6. Gas laws. 7. Dry air and moist air. Readings: Turco: p.11-27, 38-43, 366-367, 490-492; Brimblecombe: p. 1-5 1. Composition of air. The word atmosphere derives from the Greek atmo (vapor) and spherios (sphere). The Earth’s atmosphere is a mixture of gases that we call air. Air usually contains a number of small particles (atmospheric aerosols), clouds of condensed water, and ice cloud. NOTE : The atmosphere is a thin veil of gases; if our planet were the size of an apple, its atmosphere would be thick as the apple peel. Some 80% of the mass of the atmosphere is within 10 km of the surface of the Earth, which has a diameter of about 12,742 km. The Earth’s atmosphere as a mixture of gases is characterized by pressure, temperature, and density which vary with altitude (will be discussed in Lecture 4). The atmosphere below about 100 km is called Homosphere. This part of the atmosphere consists of uniform mixtures of gases as illustrated in Table 3.1. 1 Table 3.1. The composition of air. Gases Fraction of air Constant gases Nitrogen, N2 78.08% Oxygen, O2 20.95% Argon, Ar 0.93% Neon, Ne 0.0018% Helium, He 0.0005% Krypton, Kr 0.00011% Xenon, Xe 0.000009% Variable gases Water vapor, H2O 4.0% (maximum, in the tropics) 0.00001% (minimum, at the South Pole) Carbon dioxide, CO2 0.0365% (increasing ~0.4% per year) Methane, CH4 ~0.00018% (increases due to agriculture) Hydrogen, H2 ~0.00006% Nitrous oxide, N2O ~0.00003% Carbon monoxide, CO ~0.000009% Ozone, O3 ~0.000001% - 0.0004% Fluorocarbon 12, CF2Cl2 ~0.00000005% Other gases 1% Oxygen 21% Nitrogen 78% 2 • Some gases in Table 3.1 are called constant gases because the ratio of the number of molecules for each gas and the total number of molecules of air do not change substantially from time to time or place to place. -

Known As the Dispersed Phase), Distributed Throughout a Continuous Phase (Known As Dispersion Medium)

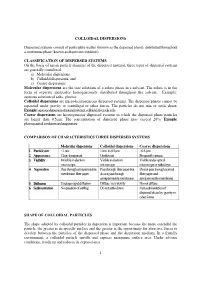

COLLOIDAL DISPERSIONS Dispersed systems consist of particulate matter (known as the dispersed phase), distributed throughout a continuous phase (known as dispersion medium). CLASSIFICATION OF DISPERSED SYSTEMS On the basis of mean particle diameter of the dispersed material, three types of dispersed systems are generally considered: a) Molecular dispersions b) Colloidal dispersions, and c) Coarse dispersions Molecular dispersions are the true solutions of a solute phase in a solvent. The solute is in the form of separate molecules homogeneously distributed throughout the solvent. Example: aqueous solution of salts, glucose Colloidal dispersions are micro-heterogeneous dispersed systems. The dispersed phases cannot be separated under gravity or centrifugal or other forces. The particles do not mix or settle down. Example: aqueous dispersion of natural polymer, colloidal silver sols, jelly Coarse dispersions are heterogeneous dispersed systems in which the dispersed phase particles are larger than 0.5µm. The concentration of dispersed phase may exceed 20%. Example: pharmaceutical emulsions and suspensions COMPARISON OF CHARACTERISTICS THREE DISPERSED SYSTEMS Molecular dispersions Colloidal dispersions Coarse dispersions 1. Particle size <1 nm 1 nm to 0.5 µm >0.5 µm 2. Appearance Clear, transparent Opalescent Frequently opaque 3. Visibility Invisible in electron Visible in electron Visible under optical microscope microscope microscope or naked eye 4. Separation Pass through semipermeable Pass through filter paper but Do not pass through -

CHAPTER 3 Transport and Dispersion of Air Pollution

CHAPTER 3 Transport and Dispersion of Air Pollution Lesson Goal Demonstrate an understanding of the meteorological factors that influence wind and turbulence, the relationship of air current stability, and the effect of each of these factors on air pollution transport and dispersion; understand the role of topography and its influence on air pollution, by successfully completing the review questions at the end of the chapter. Lesson Objectives 1. Describe the various methods of air pollution transport and dispersion. 2. Explain how dispersion modeling is used in Air Quality Management (AQM). 3. Identify the four major meteorological factors that affect pollution dispersion. 4. Identify three types of atmospheric stability. 5. Distinguish between two types of turbulence and indicate the cause of each. 6. Identify the four types of topographical features that commonly affect pollutant dispersion. Recommended Reading: Godish, Thad, “The Atmosphere,” “Atmospheric Pollutants,” “Dispersion,” and “Atmospheric Effects,” Air Quality, 3rd Edition, New York: Lewis, 1997, pp. 1-22, 23-70, 71-92, and 93-136. Transport and Dispersion of Air Pollution References Bowne, N.E., “Atmospheric Dispersion,” S. Calvert and H. Englund (Eds.), Handbook of Air Pollution Technology, New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1984, pp. 859-893. Briggs, G.A. Plume Rise, Washington, D.C.: AEC Critical Review Series, 1969. Byers, H.R., General Meteorology, New York: McGraw-Hill Publishers, 1956. Dobbins, R.A., Atmospheric Motion and Air Pollution, New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1979. Donn, W.L., Meteorology, New York: McGraw-Hill Publishers, 1975. Godish, Thad, Air Quality, New York: Academic Press, 1997, p. 72. Hewson, E. Wendell, “Meteorological Measurements,” A.C. -

Gp-Cpc-01 Units – Composition – Basic Ideas

GP-CPC-01 UNITS – BASIC IDEAS – COMPOSITION 11-06-2020 Prof.G.Prabhakar Chem Engg, SVU GP-CPC-01 UNITS – CONVERSION (1) ➢ A two term system is followed. A base unit is chosen and the number of base units that represent the quantity is added ahead of the base unit. Number Base unit Eg : 2 kg, 4 meters , 60 seconds ➢ Manipulations Possible : • If the nature & base unit are the same, direct addition / subtraction is permitted 2 m + 4 m = 6m ; 5 kg – 2.5 kg = 2.5 kg • If the nature is the same but the base unit is different , say, 1 m + 10 c m both m and the cm are length units but do not represent identical quantity, Equivalence considered 2 options are available. 1 m is equivalent to 100 cm So, 100 cm + 10 cm = 110 cm 0.01 m is equivalent to 1 cm 1 m + 10 (0.01) m = 1. 1 m • If the nature of the quantity is different, addition / subtraction is NOT possible. Factors used to check equivalence are known as Conversion Factors. GP-CPC-01 UNITS – CONVERSION (2) • For multiplication / division, there are no such restrictions. They give rise to a set called derived units Even if there is divergence in the nature, multiplication / division can be carried out. Eg : Velocity ( length divided by time ) Mass flow rate (Mass divided by time) Mass Flux ( Mass divided by area (Length 2) – time). Force (Mass * Acceleration = Mass * Length / time 2) In derived units, each unit is to be individually converted to suit the requirement Density = 500 kg / m3 . -

Solutions Mole Fraction of Component a = Xa Mass Fraction of Component a = Ma Volume Fraction of Component a = Φa Typically We

Solutions Mole fraction of component A = xA Mass Fraction of component A = mA Volume Fraction of component A = fA Typically we make a binary blend, A + B, with mass fraction, m A, and want volume fraction, fA, or mole fraction , xA. fA = (mA/rA)/((mA/rA) + (m B/rB)) xA = (mA/MWA)/((mA/MWA) + (m B/MWB)) 1 Solutions Three ways to get entropy and free energy of mixing A) Isothermal free energy expression, pressure expression B) Isothermal volume expansion approach, volume expression C) From statistical thermodynamics 2 Mix two ideal gasses, A and B p = pA + pB pA is the partial pressure pA = xAp For single component molar G = µ µ 0 is at p0,A = 1 bar At pressure pA for a pure component µ A = µ0,A + RT ln(p/p0,A) = µ0,A + RT ln(p) For a mixture of A and B with a total pressure ptot = p0,A = 1 bar and pA = xA ptot For component A in a binary mixture µ A(xA) = µ0.A + RT xAln (xA ptot/p0,A) = µ0.A + xART ln (xA) Notice that xA must be less than or equal to 1, so ln xA must be negative or 0 So the chemical potential has to drop in the solution for a solution to exist. Ideal gasses only have entropy so entropy drives mixing in this case. This can be written, xA = exp((µ A(xA) - µ 0.A)/RT) Which indicates that xA is the Boltzmann probability of finding A 3 Mix two real gasses, A and B µ A* = µ 0.A if p = 1 4 Ideal Gas Mixing For isothermal DU = CV dT = 0 Q = W = -pdV For ideal gas Q = W = nRTln(V f/Vi) Q = DS/T DS = nRln(V f/Vi) Consider a process of expansion of a gas from VA to V tot The change in entropy is DSA = nARln(V tot/VA) = - nARln(VA/V tot) Consider an isochoric mixing process of ideal gasses A and B. -

Alkali Metal Vapor Pressures & Number Densities for Hybrid Spin Exchange Optical Pumping

Alkali Metal Vapor Pressures & Number Densities for Hybrid Spin Exchange Optical Pumping Jaideep Singh, Peter A. M. Dolph, & William A. Tobias University of Virginia Version 1.95 April 23, 2008 Abstract Vapor pressure curves and number density formulas for the alkali metals are listed and compared from the 1995 CRC, Nesmeyanov, and Killian. Formulas to obtain the temperature, the dimer to monomer density ratio, and the pure vapor ratio given an alkali density are derived. Considerations and formulas for making a prescribed hybrid vapor ratio of alkali to Rb at a prescribed alkali density are presented. Contents 1 Vapor Pressure Curves 2 1.1TheClausius-ClapeyronEquation................................. 2 1.2NumberDensityFormulas...................................... 2 1.3Comparisonwithotherstandardformulas............................. 3 1.4AlkaliDimers............................................. 3 2 Creating Hybrid Mixes 11 2.1Predictingthehybridvaporratio.................................. 11 2.2Findingthedesiredmolefraction.................................. 11 2.3GloveboxMethod........................................... 12 2.4ReactionMethod........................................... 14 1 1 Vapor Pressure Curves 1.1 The Clausius-Clapeyron Equation The saturated vapor pressure above a liquid (solid) is described by the Clausius-Clapeyron equation. It is a consequence of the equality between the chemical potentials of the vapor and liquid (solid). The derivation can be found in any undergraduate text on thermodynamics (e.g. Kittel & Kroemer [1]): Δv · ∂P = L · ∂T/T (1) where P is the pressure, T is the temperature, L is the latent heat of vaporization (sublimation) per particle, and Δv is given by: Vv Vl(s) Δv = vv − vl(s) = − (2) Nv Nl(s) where V is the volume occupied by the particles, N is the number of particles, and the subscripts v & l(s) refer to the vapor & liquid (solid) respectively.