Measurement of Particle Number Density and Volume Fraction in A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ideal-Gas Mixtures and Real-Gas Mixtures

Thermodynamics: An Engineering Approach, 6th Edition Yunus A. Cengel, Michael A. Boles McGraw-Hill, 2008 Chapter 13 GAS MIXTURES Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. Permission required for reproduction or display. Objectives • Develop rules for determining nonreacting gas mixture properties from knowledge of mixture composition and the properties of the individual components. • Define the quantities used to describe the composition of a mixture, such as mass fraction, mole fraction, and volume fraction. • Apply the rules for determining mixture properties to ideal-gas mixtures and real-gas mixtures. • Predict the P-v-T behavior of gas mixtures based on Dalton’s law of additive pressures and Amagat’s law of additive volumes. • Perform energy and exergy analysis of mixing processes. 2 COMPOSITION OF A GAS MIXTURE: MASS AND MOLE FRACTIONS To determine the properties of a mixture, we need to know the composition of the mixture as well as the properties of the individual components. There are two ways to describe the composition of a mixture: Molar analysis: specifying the number of moles of each component Gravimetric analysis: specifying the mass of each component The mass of a mixture is equal to the sum of the masses of its components. Mass fraction Mole The number of moles of a nonreacting mixture fraction is equal to the sum of the number of moles of its components. 3 Apparent (or average) molar mass The sum of the mass and mole fractions of a mixture is equal to 1. Gas constant The molar mass of a mixture Mass and mole fractions of a mixture are related by The sum of the mole fractions of a mixture is equal to 1. -

Development Team

Paper No: 16 Environmental Chemistry Module: 01 Environmental Concentration Units Development Team Prof. R.K. Kohli Principal Investigator & Prof. V.K. Garg & Prof. Ashok Dhawan Co- Principal Investigator Central University of Punjab, Bathinda Prof. K.S. Gupta Paper Coordinator University of Rajasthan, Jaipur Prof. K.S. Gupta Content Writer University of Rajasthan, Jaipur Content Reviewer Dr. V.K. Garg Central University of Punjab, Bathinda Anchor Institute Central University of Punjab 1 Environmental Chemistry Environmental Environmental Concentration Units Sciences Description of Module Subject Name Environmental Sciences Paper Name Environmental Chemistry Module Name/Title Environmental Concentration Units Module Id EVS/EC-XVI/01 Pre-requisites A basic knowledge of concentration units 1. To define exponents, prefixes and symbols based on SI units 2. To define molarity and molality 3. To define number density and mixing ratio 4. To define parts –per notation by volume Objectives 5. To define parts-per notation by mass by mass 6. To define mass by volume unit for trace gases in air 7. To define mass by volume unit for aqueous media 8. To convert one unit into another Keywords Environmental concentrations, parts- per notations, ppm, ppb, ppt, partial pressure 2 Environmental Chemistry Environmental Environmental Concentration Units Sciences Module 1: Environmental Concentration Units Contents 1. Introduction 2. Exponents 3. Environmental Concentration Units 4. Molarity, mol/L 5. Molality, mol/kg 6. Number Density (n) 7. Mixing Ratio 8. Parts-Per Notation by Volume 9. ppmv, ppbv and pptv 10. Parts-Per Notation by Mass by Mass. 11. Mass by Volume Unit for Trace Gases in Air: Microgram per Cubic Meter, µg/m3 12. -

An Empirical Model Predicting the Viscosity of Highly Concentrated

Rheol Acta &2001) 40: 434±440 Ó Springer-Verlag 2001 ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Burkhardt Dames An empirical model predicting the viscosity Bradley Ron Morrison Norbert Willenbacher of highly concentrated, bimodal dispersions with colloidal interactions Abstract The relationship between the particles. Starting from a limiting Received: 7 June 2000 Accepted: 12 February 2001 particle size distribution and viscos- value of 2 for non-interacting either ity of concentrated dispersions is of colloidal or non-colloidal particles, great industrial importance, since it e generally increases strongly with is the key to get high solids disper- decreasing particle size. For a given sions or suspensions. The problem is particle system it then can be treated here experimentally as well expressed as a function of the num- as theoretically for the special case ber average particle diameter. As a of strongly interacting colloidal consequence, the viscosity of bimo- particles. An empirical model based dal dispersions varies not only with on a generalized Quemada equation the size ratio of large to small ~ / Àe g g 1 À / is used to describe particles, but also depends on the g as a functionmax of volume fraction absolute particle size going through for mono- as well as multimodal a minimum as the size ratio increas- dispersions. The pre-factor g~ ac- es. Furthermore, the well-known counts for the shear rate dependence viscosity minimum for bimodal dis- of g and does not aect the shape of persions with volumetric mixing the g vs / curves. It is shown here ratios of around 30/70 of small to for the ®rst time that colloidal large particles is shown to vanish if interactions do not show up in the colloidal interactions contribute maximum packing parameter and signi®cantly. -

Supplement Of

Supplement of Effects of Liquid–Liquid Phase Separation and Relative Humidity on the Heterogeneous OH Oxidation of Inorganic-Organic Aerosols: Insights from Methylglutaric Acid/Ammonium Sulfate Particles Hoi Ki Lam1, Rongshuang Xu1, Jack Choczynski2, James F. Davies2, Dongwan Ham3, Mijung Song3, Andreas Zuend4, Wentao Li5, Ying-Lung Steve Tse5, Man Nin Chan 1,6 1Earth System Science Programme, Faculty of Science, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China 2Department of Chemistry, University of California Riverside, Riverside, CA, USA 3Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Jeonbuk National University, Jeollabuk-do, Republic of Korea 4Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences, McGill University, Montreal, Québec, Canada 5Departemnt of Chemistry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China’ 6The Institute of Environment, Energy and Sustainability, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China Corresponding author: [email protected] Table S1. Composition, viscosity, diffusion coefficient and mixing time scale of aqueous droplets containing 3-MGA and ammonium sulfate (AS) in an organic- to-inorganic dry mass ratio (OIR) = 1 at different RH predicted by the AIOMFAC-LLE. RH (%) 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 88 Salt-rich phase (Phase α) Mass fraction of 3-MGA 0.00132 0.00372 0.00904 0.0202 / / Mass fraction of AS 0.658 0.616 0.569 0.514 / / Mass fraction of H2O 0.341 0.380 0.422 0.466 / / Organic-rich phase (Phase β) Mass fraction of 3-MGA 0.612 0.596 0.574 0.546 / / Mass fraction of AS 0.218 0.209 0.199 0.190 -

Colloidal Suspensions

Chapter 9 Colloidal suspensions 9.1 Introduction So far we have discussed the motion of one single Brownian particle in a surrounding fluid and eventually in an extaernal potential. There are many practical applications of colloidal suspensions where several interacting Brownian particles are dissolved in a fluid. Colloid science has a long history startying with the observations by Robert Brown in 1828. The colloidal state was identified by Thomas Graham in 1861. In the first decade of last century studies of colloids played a central role in the development of statistical physics. The experiments of Perrin 1910, combined with Einstein's theory of Brownian motion from 1905, not only provided a determination of Avogadro's number but also laid to rest remaining doubts about the molecular composition of matter. An important event in the development of a quantitative description of colloidal systems was the derivation of effective pair potentials of charged colloidal particles. Much subsequent work, largely in the domain of chemistry, dealt with the stability of charged colloids and their aggregation under the influence of van der Waals attractions when the Coulombic repulsion is screened strongly by the addition of electrolyte. Synthetic colloidal spheres were first made in the 1940's. In the last twenty years the availability of several such reasonably well characterised "model" colloidal systems has attracted physicists to the field once more. The study, both theoretical and experimental, of the structure and dynamics of colloidal suspensions is now a vigorous and growing subject which spans chemistry, chemical engineering and physics. A colloidal dispersion is a heterogeneous system in which particles of solid or droplets of liquid are dispersed in a liquid medium. -

Particle Characterisation In

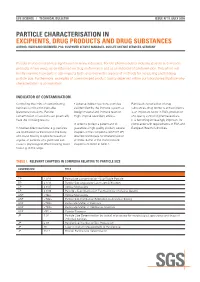

LIFE SCIENCE I TECHNICAL BULLETIN ISSUE N°11 /JULY 2008 PARTICLE CHARACTERISATION IN EXCIPIENTS, DRUG PRODUCTS AND DRUG SUBSTANCES AUTHOR: HILDEGARD BRÜMMER, PhD, CUSTOMER SERVICE MANAGER, SGS LIFE SCIENCE SERVICES, GERMANY Particle characterization has significance in many industries. For the pharmaceutical industry, particle size impacts products in two ways: as an influence on drug performance and as an indicator of contamination. This article will briefly examine how particle size impacts both, and review the arsenal of methods for measuring and tracking particle size. Furthermore, examples of compromised product quality observed within our laboratories illustrate why characterization is so important. INDICATOR OF CONTAMINATION Controlling the limits of contaminating • Adverse indirect reactions: particles Particle characterisation of drug particles is critical for injectable are identified by the immune system as substances, drug products and excipients (parenteral) solutions. Particle foreign material and immune reaction is an important factor in R&D, production contamination of solutions can potentially might impose secondary effects. and quality control of pharmaceuticals. have the following results: It is becoming increasingly important for In order to protect a patient and to compliance with requirements of FDA and • Adverse direct reactions: e.g. particles guarantee a high quality product, several European Health Authorities. are distributed via the blood in the body chapters in the compendia (USP, EP, JP) and cause toxicity to specific tissues or describe techniques for characterisation organs, or particles of a given size can of limits. Some of the most relevant cause a physiological effect blocking blood chapters are listed in Table 1. flow e.g. in the lungs. -

Chapter 3 Bose-Einstein Condensation of an Ideal

Chapter 3 Bose-Einstein Condensation of An Ideal Gas An ideal gas consisting of non-interacting Bose particles is a ¯ctitious system since every realistic Bose gas shows some level of particle-particle interaction. Nevertheless, such a mathematical model provides the simplest example for the realization of Bose-Einstein condensation. This simple model, ¯rst studied by A. Einstein [1], correctly describes important basic properties of actual non-ideal (interacting) Bose gas. In particular, such basic concepts as BEC critical temperature Tc (or critical particle density nc), condensate fraction N0=N and the dimensionality issue will be obtained. 3.1 The ideal Bose gas in the canonical and grand canonical ensemble Suppose an ideal gas of non-interacting particles with ¯xed particle number N is trapped in a box with a volume V and at equilibrium temperature T . We assume a particle system somehow establishes an equilibrium temperature in spite of the absence of interaction. Such a system can be characterized by the thermodynamic partition function of canonical ensemble X Z = e¡¯ER ; (3.1) R where R stands for a macroscopic state of the gas and is uniquely speci¯ed by the occupa- tion number ni of each single particle state i: fn0; n1; ¢ ¢ ¢ ¢ ¢ ¢g. ¯ = 1=kBT is a temperature parameter. Then, the total energy of a macroscopic state R is given by only the kinetic energy: X ER = "ini; (3.2) i where "i is the eigen-energy of the single particle state i and the occupation number ni satis¯es the normalization condition X N = ni: (3.3) i 1 The probability -

Calculation Exercises with Answers and Solutions

Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics Calculation Exercises Contents Exercise A, chapter 1 - 3 in Jacob …………………………………………………… 2 Exercise B, chapter 4, 6 in Jacob …………………………………………………… 6 Exercise C, chapter 7, 8 in Jacob, OH on aerosols and booklet by Heintzenberg … 11 Exercise D, chapter 9 in Jacob………………………………………………………. 16 Exercise E, chapter 10 in Jacob……………………………………………………… 20 Exercise F, chapter 11 - 13 in Jacob………………………………………………… 24 Answers and solutions …………………………………………………………………. 29 Note that approximately 40% of the written exam deals with calculations. The remainder is about understanding of the theory. Exercises marked with an asterisk (*) are for the most interested students. These exercises are more comprehensive and/or difficult than questions appearing in the written exam. 1 Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics – Exercise A, chap. 1 – 3 Recommended activity before exercise: Try to solve 1:1 – 1:5, 2:1 – 2:2 and 3:1 – 3:2. Summary: Concentration Example Advantage Number density No. molecules/m3, Useful for calculations of reaction kmol/m3 rates in the gas phase Partial pressure Useful measure on the amount of a substance that easily can be converted to mixing ratio Mixing ratio ppmv can mean e.g. Concentration relative to the mole/mole or partial concentration of air molecules. Very pressure/total pressure useful because air is compressible. Ideal gas law: PV = nRT Molar mass: M = m/n Density: ρ = m/V = PM/RT; (from the two equations above) Mixing ratio (vol): Cx = nx/na = Px/Pa ≠ mx/ma Number density: Cvol = nNav/V 26 -1 Avogadro’s -

Lecture 3. the Basic Properties of the Natural Atmosphere 1. Composition

Lecture 3. The basic properties of the natural atmosphere Objectives: 1. Composition of air. 2. Pressure. 3. Temperature. 4. Density. 5. Concentration. Mole. Mixing ratio. 6. Gas laws. 7. Dry air and moist air. Readings: Turco: p.11-27, 38-43, 366-367, 490-492; Brimblecombe: p. 1-5 1. Composition of air. The word atmosphere derives from the Greek atmo (vapor) and spherios (sphere). The Earth’s atmosphere is a mixture of gases that we call air. Air usually contains a number of small particles (atmospheric aerosols), clouds of condensed water, and ice cloud. NOTE : The atmosphere is a thin veil of gases; if our planet were the size of an apple, its atmosphere would be thick as the apple peel. Some 80% of the mass of the atmosphere is within 10 km of the surface of the Earth, which has a diameter of about 12,742 km. The Earth’s atmosphere as a mixture of gases is characterized by pressure, temperature, and density which vary with altitude (will be discussed in Lecture 4). The atmosphere below about 100 km is called Homosphere. This part of the atmosphere consists of uniform mixtures of gases as illustrated in Table 3.1. 1 Table 3.1. The composition of air. Gases Fraction of air Constant gases Nitrogen, N2 78.08% Oxygen, O2 20.95% Argon, Ar 0.93% Neon, Ne 0.0018% Helium, He 0.0005% Krypton, Kr 0.00011% Xenon, Xe 0.000009% Variable gases Water vapor, H2O 4.0% (maximum, in the tropics) 0.00001% (minimum, at the South Pole) Carbon dioxide, CO2 0.0365% (increasing ~0.4% per year) Methane, CH4 ~0.00018% (increases due to agriculture) Hydrogen, H2 ~0.00006% Nitrous oxide, N2O ~0.00003% Carbon monoxide, CO ~0.000009% Ozone, O3 ~0.000001% - 0.0004% Fluorocarbon 12, CF2Cl2 ~0.00000005% Other gases 1% Oxygen 21% Nitrogen 78% 2 • Some gases in Table 3.1 are called constant gases because the ratio of the number of molecules for each gas and the total number of molecules of air do not change substantially from time to time or place to place. -

2. Classical Gases

2. Classical Gases Our goal in this section is to use the techniques of statistical mechanics to describe the dynamics of the simplest system: a gas. This means a bunch of particles, flying around in a box. Although much of the last section was formulated in the language of quantum mechanics, here we will revert back to classical mechanics. Nonetheless, a recurrent theme will be that the quantum world is never far behind: we’ll see several puzzles, both theoretical and experimental, which can only truly be resolved by turning on ~. 2.1 The Classical Partition Function For most of this section we will work in the canonical ensemble. We start by reformu- lating the idea of a partition function in classical mechanics. We’ll consider a simple system – a single particle of mass m moving in three dimensions in a potential V (~q ). The classical Hamiltonian of the system3 is the sum of kinetic and potential energy, p~ 2 H = + V (~q ) 2m We earlier defined the partition function (1.21) to be the sum over all quantum states of the system. Here we want to do something similar. In classical mechanics, the state of a system is determined by a point in phase space.Wemustspecifyboththeposition and momentum of each of the particles — only then do we have enough information to figure out what the system will do for all times in the future. This motivates the definition of the partition function for a single classical particle as the integration over phase space, 1 3 3 βH(p,q) Z = d qd pe− (2.1) 1 h3 Z The only slightly odd thing is the factor of 1/h3 that sits out front. -

Particle Number Concentrations and Size Distribution in a Polluted Megacity

https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2020-6 Preprint. Discussion started: 17 February 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. Particle number concentrations and size distribution in a polluted megacity: The Delhi Aerosol Supersite study Shahzad Gani1, Sahil Bhandari2, Kanan Patel2, Sarah Seraj1, Prashant Soni3, Zainab Arub3, Gazala Habib3, Lea Hildebrandt Ruiz2, and Joshua S. Apte1 1Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering, The University of Texas at Austin, Texas, USA 2McKetta Department of Chemical Engineering, The University of Texas at Austin, Texas, USA 3Department of Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, New Delhi, India Correspondence: Joshua S. Apte ([email protected]), Lea Hildebrandt Ruiz ([email protected]) Abstract. The Indian national capital, Delhi, routinely experiences some of the world's highest urban particulate matter concentrations. While fine particulate matter (PM2.5) mass concentrations in Delhi are at least an order of magnitude higher than in many western cities, the particle number (PN) concentrations are not similarly elevated. Here we report on 1.25 years of highly 5 time resolved particle size distributions (PSD) data in the size range of 12–560 nm. We observed that the large number of accumulation mode particles—that constitute most of the PM2.5 mass—also contributed substantially to the PN concentrations. The ultrafine particles (UFP, Dp <100 nm) fraction of PN was higher during the traffic rush hours and for daytimes of warmer seasons—consistent with traffic and nucleation events being major sources of urban UFP. UFP concentrations were found to be relatively lower during periods with some of the highest mass concentrations. -

Statistical Physics 06/07

STATISTICAL PHYSICS 06/07 Quantum Statistical Mechanics Tutorial Sheet 3 The questions that follow on this and succeeding sheets are an integral part of this course. The code beside each question has the following significance: • K: key question – explores core material • R: review question – an invitation to consolidate • C: challenge question – going beyond the basic framework of the course • S: standard question – general fitness training! 3.1 Particle Number Fluctuations for Fermions [s] (a) For a single fermion state in the grand canonical ensemble, show that 2 h(∆nj) i =n ¯j(1 − n¯j) wheren ¯j is the mean occupancy. Hint: You only need to use the exclusion principle not the explict form ofn ¯j. 2 How is the fact that h(∆nj) i is not in general small compared ton ¯j to be reconciled with the sharp values of macroscopic observables? (b) For a gas of noninteracting particles in the grand canonical ensemble, show that 2 X 2 h(∆N) i = h(∆nj) i j (you will need to invoke that nj and nk are uncorrelated in the GCE for j 6= k). Hence show that for noninteracting Fermions Z h(∆N)2i = g() f(1 − f) d follows from (a) where f(, µ) is the F-D distribution and g() is the density of states. (c) Show that for low temperatures f(1 − f) is sharply peaked at = µ, and hence that 2 h∆N i ' kBT g(F ) where F = µ(T = 0) R ∞ ex dx [You may use without proof the result that −∞ (ex+1)2 = 1.] 3.2 Entropy of the Ideal Fermi Gas [C] The Grand Potential for an ideal Fermi is given by X Φ = −kT ln [1 + exp β(µ − j)] j Show that for Fermions X Φ = kT ln(1 − pj) , j where pj = f(j) is the probability of occupation of the state j.