Forests and Forest Industries Grays Harbor Unit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forestry Books, 1820-1945

WASHINGTON STATE FORESTRY BIBLIOGRAPHY: BOOKS, 1820‐1945 (334 titles) WASHINGTON STATE FORESTRY BIBLIOGRAPHY BOOKS (published between 1820‐1945) 334 titles Overview This bibliography was created by the University of Washington Libraries as part of the Preserving the History of U.S. Agriculture and Rural Life Grant Project funded and supported by the National Endowment of the Humanities (NEH), Cornell University, the United States Agricultural Information Network (USAIN), and other land‐grant universities. Please note that this bibliography only covers titles published between 1820 and 1945. It excludes federal publications; articles or individual numbers from serials; manuscripts and archival materials; and maps. More information about the creation and organization of this bibliography, the other available bibliographies on Washington State agriculture, forestry, and fisheries, and the Preserving the History of U.S. Agriculture and Rural Life Grant Project for Washington State can be found at: http://www.lib.washington.edu/preservation/projects/WashAg/index.html Citation University of Washington Libraries (2005). Washington State Agricultural Bibliography. Retrieved from University of Washington Libraries Preservation Web site, http://www.lib.washington.edu/preservation/projects/WashAg/index.html © University of Washington Libraries, 2005, p. 1 WASHINGTON STATE FORESTRY BIBLIOGRAPHY: BOOKS, 1820‐1945 (334 titles) 1. After the War...Wood! s.l.: [1942]. (16 p.). 2. Cash crops from Washington woodlands. S.l.: s.n., 1940s. (30 p., ill. ; 22 cm.). 3. High‐ball. Portland, Ore.: 1900‐1988? (32 p. illus.). Note: "Logging camp humor." Other Title: Four L Lumber news. 4. I.W.W. case at Centralia; Montesano labor jury dares to tell the truth. Tacoma: 1920. -

Supreme Court of the United States ______

No. 19-247 In the Supreme Court of the United States __________________ CITY OF BOISE, IDAHO, Petitioner, v. ROBERT MARTIN, ET AL., Respondents. __________________ On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit __________________ BRIEF OF THE CITY OF ABERDEEN, WASHINGTON AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF THE CITY OF BOISE __________________ JOHN EDWARD JUSTICE MARY PATRICE KENT JEFFREY SCOTT MYERS Corporation Counsel Law, Lyman, Daniel, Counsel of Record Kamerrer & Bogdanovich, P.S. Office of Corporation Counsel, Post Office Box 11880 City of Aberdeen Olympia, WA 98508-1880 200 East Market Street (360) 754-3480 Aberdeen, WA 98520 (360) 357-3511 (fax) (360) 537-3233 [email protected] (360) 532-9137 (fax) [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Amicus Curiae City of Aberdeen, Washington in Support of Petition of City of Boise Becker Gallagher · Cincinnati, OH · Washington, D.C. · 800.890.5001 i TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES . iii INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE . 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT . 2 ARGUMENT . 3 I. Context/Background . 3 II. Aberdeen Experience: River Street Property ..................................... 5 A. Background ........................ 5 B. Monroe, et al. v. City of Aberdeen, et al. 8 C. Aitken, et al. v. City of Aberdeen . 8 III. Martin does not clearly define “available overnight shelter” . 12 IV. Martin has impermissibly expanded prohibitions against criminalization to generally applicable protections of public health and welfare. 13 V. Martin has created unintended consequences including appropriating of public property for personal use; and shifting responsibility for local management of homelessness to the federal judiciary. 15 A. -

02-Grays Harbor Sediment Literature Review

Plaza 600 Building 600 Stewart Street, Suite 1700 Seattle, Washington 98101 206.728.2674 June 29, 2015 National Fisheries Conservation Center 308 Raymond Street Ojai, California 93023 Attention: Julia Sanders Subject: Cover Letter Literature Review & Support Services Grays Harbor, Washington File No. 21922-001-00 GeoEngineers has completed the literature search regarding sedimentation within Grays Harbor estuary. The attached letter report and appendices summarize our efforts to gather and evaluate technical information regarding the sedimentation conditions in Grays Harbor, and the corresponding impacts to shellfish. This literature search was completed in accordance with our signed agreement dated May 5, 2015, and is for the express use of the National Fisheries Conservation Center and its partners in this investigation. We will also provide to you electronic copies of the references contained in the bibliography. We thank you for the opportunity to support the National Fisheries Conservation Center as you investigate the sedimentation issues in Grays Harbor. We look forward to working with you to develop mitigation strategies that facilitate ongoing shellfish aquaculture in Grays Harbor. Sincerely, GeoEngineers, Inc. Timothy P. Hanrahan, PhD Wayne S. Wright, CFP, PWS Senior Fluvial Geomorphologist Senior Principal TPH:WSW:mlh Attachments: Grays Harbor Literature Review & Support Services Letter Report Figure 1. Vicinity Map Appendix A. Website Links Appendix B. Bibliography One copy submitted electronically Disclaimer: Any electronic form, facsimile or hard copy of the original document (email, text, table, and/or figure), if provided, and any attachments are only a copy of the original document. The original document is stored by GeoEngineers, Inc. and will serve as the official document of record. -

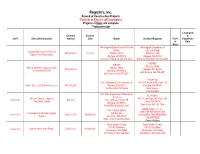

Projects *Projects in Red Are Still in Progress Projects in Black Are Complete **Subcontractor

Rognlin’s, Inc. Record of Construction Projects *Projects in Red are still in progress Projects in black are complete **Subcontractor % Complete Contract Contract & Job # Description/Location Amount Date Owner Architect/Engineer Class Completion of Date Work Washington Department of Fish and Washington Department of Wildlife Fish and Wildlife Log Jam Materials for East Fork $799,000.00 01/11/21 PO Box 43135 PO Box 43135 Satsop River Restoration Olympia, WA 98504 Olympia, WA 98504 Adrienne Stillerman 360.902.2617 Adrienne Stillerman 360.902.2617 WSDOT WSDOT PO Box 47360 SR 8 & SR 507 Thurston County PO Box 47360 $799,000.00 Olympia, WA 98504 Stormwater Retrofit Olympia, WA 98504 John Romero 360.570.6571 John Romero 360.570.6571 Parametrix City of Olympia 601 4th Avennue E. 1019 39th Avenue SE, Suite 100 Water Street Lift Station Generator $353,952.76 Olympia, WA 98501 Puyallup, WA 98374 Jim Rioux 360-507-6566 Kevin House 253.604.6600 WA State Department of Enterprise SCJ Alliance Services 14th Ave Tunnel – Improve 8730 Tallon Lane NE, Suite 200 20-80-167 $85,000 1500 Jefferson Street SE Pedestrian Safety Lacey, WA 98516 Olympia, WA 98501 Ross Jarvis 360-352-1465 Bob Willyerd 360.407.8497 ABAM Engineers, Inc. Port of Grays Harbor 33301 9th Ave S Suite 300 Terminals 3 & 4 Fender System PO Box 660 20-10-143 $395,118.79 12/08/2020 Federal Way, WA 98003-2600 Repair Aberdeen, WA 98520 (206) 357-5600 Mike Johnson 360.533.9528 Robert Wallace Grays Harbor County Grays Harbor County 100 W. -

Estuarine Studies in Upper Grays Harbor Washington

Estuarine Studies in Upper Grays Harbor Washington GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1873-B Prepared in cooperation with the Washington State Pollution Control Commission Estuarine Studies in Upper Grays Harbor Washington By JOSEPH P. BEVERAGE and MILTON N. SWECKER ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY WATER-SUPPLY PAPER 1873-B Prepared in cooperation with the Washington State Pollution Control Commission UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON: 1969 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR WALTER J. HICKEL, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY William T. Pecora, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price 45 cents (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Abstract__________._._.._______._._._._.____..__..._..._ Bl Introduction. _____________________________________________________ 2 Acknowledgments _____________________________________________ 4 Previous investigations.._______________________________________ 4 Hydrology______________________________________________________ 6 Fresh water_________________________________________________ 6 Tides_____-_____--___-______--____-____---___-_____----__--__ 12 Hydraulics of the estuary._________________________________________ 16 Velocity______________________________________________________ 17 Salinity distribution.___________________________________________ 28 Dye studies_________________________________________________ 41 Summary of estuary hydraulics.________________________________ 53 Bottom materials...-__-__________-_____-____--____-______--____-__ -

Geologic Map of the Humptulips Quadrangle and Adjacent Areas

(I) GEOLOGIC MAP OF (I) I ~ C!> THE HUMPTULIPS QUADRANGLE Q. < :E AND ADJACENT AREAS, (.) C!> GRAYS HARBOR COUNTY, WASHINGTON 0 ..J 0 w C, BY WELDON W. RAU 1986 GEOLOGIC MAP GM-33 •• WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENT or ~~~=~ Natural Resources Brtan eoyi,. • C"'1lltUSSJoMt ot Publie Lands An Sleams • SupervLSOr Division ol Geology and E(rtfh Re10Utet!! Raymond LasmaN1. Sta"' Geologut Printed In the United States of America For sale by the Department of Natural Resources, Olympia, Washington Price $ 2.78 .22 tax $ 3.00 Brtw, BO\"le • Coinmis&looor <JI f>u blk; t.wxi. Ar1 Slearn< • 5ull<l,-,.•t.o,- Geologic Map WASHINGTON STATE D~ARTMENT OF Dbtl*-1 o! GeolCVI' a.-.d Earth Resource> Natural Resources RayrnoM i.,,.....,n,.. Slcrta ~~ GM-33 probably most extensive during the Oeposition of the upper part of the formatio n. Hoh rocks of this area are likely no younger than the middle Eocene Ulatisian Stage. Northern outcrops of the Montesano Formation continue westw ard from the Hoh rocks of the 00/lSlal area are known to contain foraminifers ranging in age from Wynoochee Valley quadrangle, forming a belt of ou1crop extending to the East Fork miOdlc Eocene to middle Miocene. gf the Hoquiam Rive r. The formation is ma;t extensively c,;poscd in the southeastern part of the mapped area, mainly along the Ea.st Fo rk of the Hoquiam Ri~er and along the Wishkah River and itJ lower tributaries. In aOdilion, the format ion is particularly INTRUSIVE ROCKS (Ti) well exposed in the hill s within the cities of Aberdeen and Hoquiam. -

Economic Options for Grays Harbor

ECONOMIC OPTIONS FOR GRAYS HARBOR A Report by The Evergreen State College class “Resource Rebels: Environmental Justice Movements Building Hope,” Winter 2016 CONTENTS Preface 3 Zoltán Grossman Background 6 (Lucas Ayenew, Jess Altmayer) I. Ports and Industries 12 (Roma Castellanos, Nicole Fernandez, Jennifer Kosharek) II. Tourism and Transit 27 (Jess Altmayer, Emily Hall, Megan Moore, Lauren Shanafelt) III. Forestry and Forest Products 47 (Lucas Ayenew, Kelsey Foster, Aaron Oman) IV. Fisheries and Energy 61 (Tiffany Brown, Kris Kimmel, Kyle Linden) V. Community Issues 71 (Emily Hall, Jess Altmayer) Common Themes 81 (Roma Castellanos, Emily Hall, Kelsey Foster, Kyle Linden) Background Resources 84 Evergreen students with Quinault Indian Nation Vice President Tyson Johnston (second from right) and Quinault staff members, at Quinault Department of Natural Resources in Taholah. 2 PREFACE Zoltán Grossman In January-March 2016, students from The Evergreen State College, in Olympia, Washington, studied Economic Options in Grays Harbor, looking beyond the oil terminal debate to other possibilities for job-generating development in Aberdeen, Hoquiam, and other Grays Harbor County communities. The class worked in collaboration with the Quinault Indian Nation, the Aberdeen Revitalization Movement, and community organizations. The students were part of the Evergreen program “Resource Rebels: Environmental Justice Movements Building Hope,” which explored the intersections of environmental issues with social issues of race, class, and gender. The program was taught by myself, a geographer working in Native Studies, and Karen Gaul, an anthropologist working in Sustainability Studies. In fall quarter, the class focused on Native American environmental justice issues, and hosted the 1st annual Indigenous Climate Justice Symposium at the Evergreen Longhouse, which included Quinault Indian Nation President Fawn Sharp. -

Water System Plan

City of Ocean Shores CITY OF OCEAN SHORES WATER SYSTEM PLAN SYSTEM WATER CITY OF OCEAN SHORES WATER SYSTEM PLAN Prepared By: Prepared By: CITY OF OCEAN SHORES WATER SYSTEM PLAN Prepared for: City of Ocean Shores 710 Point Brown Avenue N.W. Ocean Shores, WA 98569 Prepared by: PACE Engineers, Inc. 11255 Kirkland Way, Suite 300 PROJECT CERTIFICATION The technical material and data contained in this Water System Plan was prepared by PACE Engineers, Inc. under the supervision of the below listed individuals. Those responsible staff members who are registered professional engineers are licensed in the State of Washington. Susan E. Boyd Vice President, Project Principal William Reynolds, P.E. Principal Engineer Page i This Page Intentionally Blank Executive Summary This Comprehensive Plan is a compilation of planning and engineering studies completed by PACE Engineers, Inc. The purpose of this Plan is to evaluate the City of Ocean Shores water system for its ability to meet the existing and projected needs of the customers of the City. This Plan supersedes the previous 2005 Water System Plan and has been prepared under the direction of the City of Ocean Shores City Council and Department of Public Works to meet the specific needs of the City while complying with Chapter 246-290 of the Washington Administrative Code (WAC) establishing planning requirements for public water systems. The Plan is also in accordance with the federal, state, and local rules and regulations governing the operation of public water systems as administered by the State of Washington Departments of Health and Ecology and, the codes and policies of Grays Harbor County. -

Cultural Resources Report Cover Sheet

40600-HS-MEM-55030 Revision 1 6 December 2018 CULTURAL RESOURCES REPORT COVER SHEET Author: Lauran R. Switzer, January M. Tavel, and Andrea Dumovich Title of Report: Archaeological Monitoring Results for the BHP Billiton Canada, Inc. Proposed Grays Harbor Potash Export Facility Mitigation Area, IDD No. 1 and Historic Context for Mitigation Area, POGH Terminal 4 Date of Report: November 2018 County: Grays Harbor Section: 10, 17, 18 Township: 17N Range: 9W, 10W Quad: Aberdeen, Hoquiam Acres: 49.29 PDF of report submitted (REQUIRED) Yes Historic Property Export Files submitted? Yes No Archaeological Site(s)/Isolate(s) Found or Amended? Yes No TCP(s) found? Yes No Replace a draft? Yes No Satisfy a DAHP Archaeological Excavation Permit requirement? Yes # No DAHP Archaeological Site #: N/A Memorandum To: April Ryckman, Environmental Scientist BergerABAM 1301 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1200 Seattle, WA 98101-2677 From: Lauran R. Switzer, MA, RPA ICF Senior Archaeologist Date: November 30, 2018 Re: Archaeological Monitoring Results for the BHP Billiton Canada, Inc. Proposed Grays Harbor Potash Export Facility Mitigation Area, IDD No. 1 and Historic Context for Mitigation Area, POGH Terminal 4 BHP Billiton Canada, Inc. (BHP) proposes to redevelop the Port of Grays Harbor’s (Port) existing Terminal 3 facility and adjacent parcels in Hoquiam, WA for the Grays Harbor Export Facility (proposed project), a bulk potash export facility. The project would require permits from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and, therefore, would be a federal undertaking. As a result, the project would need to be performed in compliance with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA). -

Chehalis River

Chehalis River 1 GRAYS HARBOR, HOQUIAM, WASHINGTON THE OFFERING The subject property is located next to the Port of Grays Harbor on the southwest corner of the Olympic Peninsula. The property previously operated as a pulp and paper mill for many years; the pulp mill and paper mill ceased to operate in 1992 and 2013, respectively. This location in Grays Harbor County is ideal for ocean going vessels due to the deep-water moorage available to ships and its close proximity to the ocean. It takes approximately one hour for a ship to enter Grays Harbor from the ocean and dock at the subject site and roughly one hour to travel from the site to Interstate 5. From there, it is approximately one hour to Seattle, one-half hour to Tacoma and two hours to Portland. Strengths • The site lays out well for industrial activity in addition to water-related activities • Property division is simple due to its configuration of 9 separate tax parcels • Close to Pacific Ocean via Chehalis River channel (10 miles or 1 hour) • Channel depth in Chehalis River is 36 feet/dock depth 32 feet—may be able to take the depth to 43 feet • All major infrastructure is in place for the site, including rail access, sewer, water, storm water and access on city streets • Scarcity of waterfront property combined with the emerging pool of new users for industrial grade product is leading to increased prices and pressure for changes in heavy industrial zone classifications and allowed uses • The Grays Harbor area has a skilled employment base for heavy industrial uses • Proximity -

5.10 Grays Harbor Tributaries Ecological Region

Ecological Regions: Grays Harbor Tributaries Ecological Region 5.10 Grays Harbor Tributaries Ecological Region 5.10.1 Overview The Grays Harbor Tributaries Ecological Region encompasses the tributaries that directly enter Grays Harbor (other than the Chehalis River) and the Wishkah River that enters the Chehalis River at RM 0 (Figure 5-19). This ecological region encompasses more than 600 square miles (nearly 385,000 acres) and represents approximately 22% of the overall Chehalis Basin. The ecological region is diverse, with drainages from the Olympic Mountains and lower Coast Range areas. The highest point in this ecological region is Gibson Peak at 4,390 feet. The Humptulips Important Features and Functions River arises in two forks within the Olympic National • The amount of tidally influenced Forest at about 3,000 feet in elevation and flows for freshwater wetland with Sitka spruce 60 miles to Grays Harbor. The Hoquiam River arises in swamp in the ecological region is unique in the basin and much different from the the low foothills of the Olympic Mountains in three deciduous-dominated forest in the forks at about 400 feet in elevation; the East Fork Chehalis River Tidal Ecological Region. Hoquiam River is the longest and flows for 17 miles. A • The maritime climate provides a year- significant part of the Middle Fork and West Fork round buffer to air (and water) temperatures. Hoquiam rivers are within the City of Hoquiam • The Humptulips River sub-basin municipal watershed. The Wishkah River arises in the characteristics are important and unique: foothills of the Olympic Mountains at about these feature a smaller percentage of the 1,200 feet in elevation; the upper watershed of the total length in tidewater, substantial spawning gravel, and close proximity to Wishkah River is within the City of Aberdeen’s the ocean. -

Year Three Report March 2014

Grays Harbor College Year 3 Report – March 2014 GRAYS HARBOR COLLEGE Year Three Report March 2014 Prepared for the Northwest Commission on Colleges and Universities NWCCU Revised Standards and Process Grays Harbor College Year 3 Report – March 2014 Contents Institutional Overview 1 Basic Institutional Data Form 3 Preface 9 Chapter 1: Mission, Core Themes, and Expectations 11 Section I: Executive Summary of Eligibility Requirements 2 and 3 11 Section II: Mission (Standard 1.A) 12 Mission Statement 12 Interpretation of Mission Fulfillment 12 Articulation of Acceptable Threshold of Mission Fulfillment 13 Section III: Core Themes (Standard 1.B) 15 Core Theme 1: Academic Transfer 15 Core Theme 2: Workforce Preparation 16 Core Theme 3: Basic Skills 17 Core Theme 4: Service to Community 18 Rationale for Measurability of Achievement 19 Chapter Two: Resources and Capacity 22 Section I: Executive Summary of Eligibility Requirements 4 through 21 22 Section II: Governance (Standard 2.A) 26 Section III: Human Resources (Standard 2.B) 29 Section IV: Educational Resources (Standard 2.C) 30 Section V: Student Support Resources (Standard 2.D) 40 Section VI: Library and Information Resources (Standard 2.E) 44 Section VII: Financial Resources (Standard 2.F) 46 Section VIII: Physical and Technical Infrastructure (Standard 2.G) 47 Year Three Report Conclusion 52 Appendix: Sample Mission Fulfillment Scorecards 53 Data Sources 58 Grays Harbor College Year 3 Report – March 2014 Index of Tables, Charts and Figures Chart 1.0.1 2011-2012 Comparative Demographic