Lessons on Political Violence from America's Post-9/11 Wars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Individuals and Organisations

Designated individuals and organisations Listed below are all individuals and organisations currently designated in New Zealand as terrorist entities under the provisions of the Terrorism Suppression Act 2002. It includes those listed with the United Nations (UN), pursuant to relevant Security Council Resolutions, at the time of the enactment of the Terrorism Suppression Act 2002 and which were automatically designated as terrorist entities within New Zealand by virtue of the Acts transitional provisions, and those subsequently added by virtue of Section 22 of the Act. The list currently comprises 7 parts: 1. A list of individuals belonging to or associated with the Taliban By family name: • A • B,C,D,E • F, G, H, I, J • K, L • M • N, O, P, Q • R, S • T, U, V • W, X, Y, Z 2. A list of organisations belonging to or associated with the Taliban 3. A list of individuals belonging to or associated with ISIL (Daesh) and Al-Qaida By family name: • A • B • C, D, E • F, G, H • I, J, K, L • M, N, O, P • Q, R, S, T • U, V, W, X, Y, Z 4. A list of organisations belonging to or associated with ISIL (Daesh) and Al-Qaida 5. A list of entities where the designations have been deleted or consolidated • Individuals • Entities 6. A list of entities where the designation is pursuant to UNSCR 1373 1 7. A list of entities where the designation was pursuant to UNSCR 1373 but has since expired or been revoked Several identifiers are used throughout to categorise the information provided. -

Badghis Province

AFGHANISTAN Badghis Province District Atlas April 2014 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. http://afg.humanitarianresponse.info [email protected] AFGHANISTAN: Badghis Province Reference Map 63°0'0"E 63°30'0"E 64°0'0"E 64°30'0"E 65°0'0"E Legend ^! Capital Shirintagab !! Provincial Center District ! District Center Khwajasabzposh Administrative Boundaries TURKMENISTAN ! International Khwajasabzposh Province Takhta Almar District 36°0'0"N 36°0'0"N Bazar District Distirict Maymana Transportation p !! ! Primary Road Pashtunkot Secondary Road ! Ghormach Almar o Airport District p Airfield River/Stream ! Ghormach Qaysar River/Lake ! Qaysar District Pashtunkot District ! Balamurghab Garziwan District Bala 35°30'0"N 35°30'0"N Murghab District Kohestan ! Fa r y ab Kohestan Date Printed: 30 March 2014 08:40 AM Province District Data Source(s): AGCHO, CSO, AIMS, MISTI Schools - Ministry of Education ° Health Facilities - Ministry of Health Muqur Charsadra Badghis District District Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS-84 Province Abkamari 0 20 40Kms ! ! ! Jawand Muqur Disclaimers: Ab Kamari Jawand The designations employed and the presentation of material !! District p 35°0'0"N 35°0'0"N Qala-e-Naw District on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, Qala-i-Naw Qadis city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation District District of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Lessons on Political Violence from America's Post–9/11 Wars

Review Feature Journal of Conflict Resolution 2018, Vol. 62(1) 174-202 ª The Author(s) 2016 Lessons on Political Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0022002716669808 Violence from America’s journals.sagepub.com/home/jcr Post–9/11 Wars Christoph Mikulaschek1, and Jacob N. Shapiro1 Abstract A large literature has emerged in political science that studies the wars in Afgha- nistan and Iraq. This article summarizes the lessons learned from this literature, both theoretical and practical. To put this emerging knowledge base into perspective, we review findings along two dimensions of conflict: factors influencing whether states or substate groups enter into conflict in the first place and variables affecting the intensity of fighting at particular times and places once war has started. We then discuss the external validity issues entailed in learning about contemporary wars and insurgencies from research focused on the Afghanistan and Iraq wars during the period of US involvement. We close by summarizing the uniquely rich qualitative and quantitative data on these wars (both publicly available and what likely exists but has not been released) and outline potential avenues for future research. Keywords civil wars, conflict, military intervention, foreign policy, asymmetric conflict, civilian casualties One consequence of America’s post–9/11 wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere has been a profusion of new scholarship on civil war and insurgency. There have been at least 275 studies on these conflicts published in academic journals or pre- sented at major political science conferences since 2002 as well as more than eighty 1Politics Department, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA Corresponding Author: Jacob N. -

Chronology of Events in Afghanistan, November 2003*

Chronology of Events in Afghanistan, November 2003* November 1 "Unidentified men" torch district office in Konar Province. (Pakistan-based Afghan Islamic Press news agency / AIP) “Unidentified men” reportedly captured Watapur District office in Konar Province and set it on fire after taking control of it for two hours. The sources said the assailants did not harm staff of the district and warned government staff not to come there again. It is said the assailants took the weapons from the district office with them. Watapur is located about 35 km to the east of Asadabad, the capital of Konar Province. UN office attacked in Jalalabad. (Iranian radio Voice of the Islamic Republic of Iran) A rocket attack was carried out on a UN office in Jalalabad, the capital of Nangarhar Province. It was reported that no losses and casualties were sustained in the attacks. District attacked by gunmen in Nangarhar province. (Associated Press / AP) Officials in the Rodat district of the Nangarhar province said assailants opened fire with assault rifles and machine guns at the headquarters of the local administration. Security forces returned fire and beat back the attackers in an hour-long gun-battle, said Mohammed Asif Qazizada, Nangarhar's deputy governor. Blast claims two lives in Khost Province. (Voice of the Islamic Republic of Iran) As a result of an explosion two people have been killed and two others injured in Yaqobi District, Khost Province. The commander of Military Division No 25, Gen Khiyal Baz, confirmed the report and said that the explosion took place as a result of a conflict between two tribes in the area. -

Afghanistan Bibliography 2019

Afghanistan Analyst Bibliography 2019 Compiled by Christian Bleuer Afghanistan Analysts Network Kabul 3 Afghanistan Analyst Bibliography 2019 Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN), Kabul, Afghanistan This work is licensed under this creative commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode The Afghanistan Analysts Network (AAN) is a non-profit, independent policy research organisation. It aims to bring together the knowledge, experience and drive of a large number of experts to better inform policy and to increase the understanding of Afghan realities. It is driven by engagement and curiosity and is committed to producing independent, high quality and research-based analysis on developments in Afghanistan. The institutional structure of AAN includes a core team of analysts and a network of contributors with expertise in the fields of Afghan politics, governance, rule of law, security, and regional affairs. AAN publishes regular in-depth thematic reports, policy briefings and comments. The main channel for dissemination of these publications is the AAN web site: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/ Cover illustration: “City of Kandahar, with main bazaar and citadel, Afghanistan.” Lithograph by Lieutenant James Rattray, c. 1847. Coloured by R. Carrick. TABLE OF CONTENTS Bibliography Introduction and Guide ..................................................................... 6 1. Ethnic Groups ................................................................................................... -

Name (Original Script): ﻦﯿﺳﺎﺒﻋ ﺰﻳﺰﻌﻟا ﺪﺒﻋ ﻧﺸﻮان ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﺮزاق ﻋﺒﺪ

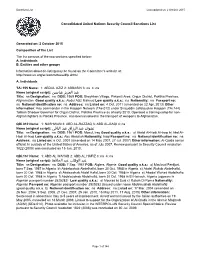

Sanctions List Last updated on: 2 October 2015 Consolidated United Nations Security Council Sanctions List Generated on: 2 October 2015 Composition of the List The list consists of the two sections specified below: A. Individuals B. Entities and other groups Information about de-listing may be found on the Committee's website at: http://www.un.org/sc/committees/dfp.shtml A. Individuals TAi.155 Name: 1: ABDUL AZIZ 2: ABBASIN 3: na 4: na ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﻌﺰﻳﺰ ﻋﺒﺎﺳﯿﻦ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1969 POB: Sheykhan Village, Pirkowti Area, Orgun District, Paktika Province, Afghanistan Good quality a.k.a.: Abdul Aziz Mahsud Low quality a.k.a.: na Nationality: na Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 4 Oct. 2011 (amended on 22 Apr. 2013) Other information: Key commander in the Haqqani Network (TAe.012) under Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani (TAi.144). Taliban Shadow Governor for Orgun District, Paktika Province as of early 2010. Operated a training camp for non- Afghan fighters in Paktika Province. Has been involved in the transport of weapons to Afghanistan. QDi.012 Name: 1: NASHWAN 2: ABD AL-RAZZAQ 3: ABD AL-BAQI 4: na ﻧﺸﻮان ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﺮزاق ﻋﺒﺪ اﻟﺒﺎﻗﻲ :(Name (original script Title: na Designation: na DOB: 1961 POB: Mosul, Iraq Good quality a.k.a.: a) Abdal Al-Hadi Al-Iraqi b) Abd Al- Hadi Al-Iraqi Low quality a.k.a.: Abu Abdallah Nationality: Iraqi Passport no: na National identification no: na Address: na Listed on: 6 Oct. 2001 (amended on 14 May 2007, 27 Jul. -

THE ANSO REPORT Page 1

CONFIDENTIAL— NGO use only No copy, forward or sale © INSO 2012 Issue 98 REPORT 16‐31 May 2012 Index COUNTRY SUMMARY Central Region 1-4 As of the end of May, AOG activity vol- distribution, the AOG tactical portfolio 5-10 Northern Region umes this year stayed 40% below the vol- remains relatively consistent. Opposition Western Region 11-12 umes for the same actor and period in 2011 activity remains driven by conventional (for the comparison of AOG activity vol- attacks (SAF, RPG, etc), followed by IED Eastern Region 13-16 umes, see graph on p. 20). Nonetheless, and indirect fire (rocket, mortar, etc). This AOG incidents exhibited a 32% increase month, close range attacks constituted Southern Region 17-21 between May and April, displaying a pro- 61%, of all AOG attacks, IED strikes 29% 22 ANSO Info Page portionate growth well in line with the and indirect fire 10%. Although present, trends established last year and in 2010. suicide and complex attacks did not repre- Whereas the opposition activity in 2010 sent any significant proportion in terms of HIGHLIGHTS culminated with the parliamentary elections volumes, but continue to be used as a force in September, 2011 did not include any multiplier in the battlefield, in assassination AOG mobility in such milestone and the conflict reached its campaigns or as pure ‘statement attacks’ in Ghazni peak in July after a very intensive late- urban areas, where the conflict engage- spring and early-summer campaign. A ments increasingly converge. Potential for com- steep growth between May and June is also plex attacks in ur- Casualty figures also highlight the ongoing to be expected this year, although the ban centers importance of IED deployment in the op- AOG activity volumes will remain well position campaign. -

World Bank Document

AFGHANISTAN EDUCATION QUALITY IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM-II Public Disclosure Authorized MINISTRY OF EDUCATION PROCUREMENT PLAN FY2008-10-11 Public Disclosure Authorized Procurement Management Unit Education Quality Imrpovement Program-II Revised Procurement Plan EQUIP II (Revision Ref.: 04 on 15-05-10) General Public Disclosure Authorized 1 Project information: Education Quality Improvement Project II (EQUIP II) Country: Afghanistan Borrower: Islamic Republic of Afghanistan Project Name: Education Quality Improvement Project II (EQUIP II) Grant No.: H 354 –AF Project ID : P106259 P106259 Project Implementing Agency: Ministry of Education of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan 2 Bank’s approval date of the procurement Plan : 17 Nov.2007 (Original:) 3 Period covered by this procurement plan: One year Procurement for the proposed project would be carried out in accordance with the World Bank’s “Guidelines: Procurement Under IBRD Loans and IDA Credits” dated May 2004; and “Guidelines: Selection and Employment of Consultants by World Bank Borrowers” dated May 2004, and the provisions stipulated in the Legal Agreement. The procurement will be done through competitive bidding using the Bank’s Standard Bidding Documents (SBD). The general description of various items under different expenditure category are described. For each contract to Public Disclosure Authorized be financed by the Loan/Credit, the different procurement methods or consultant selection methods, estimated costs, prior review requirements, and time frame are agreed between the Recipient and the Bank project team in the Procurement Plan. The Procurement Plan will be updated at least annually or as required to reflect the actual project implementation needs and improvements in institutional capacity. II. Goods and Works and consulting services. -

Civilian Casualties During 2007

UNITED NATIONS UNITED NATIONS ASSISTANCE MISSION IN AFGHANISTAN UNAMA CIVILIAN CASUALTIES DURING 2007 Introduction: The figures contained in this document are the result of reports received and investigations carried out by UNAMA, principally the Human Rights Unit, during 2007 and pursuant to OHCHR’s monitoring mandate. Although UNAMA’s invstigations pursue reliability through the use of generally accepted procedures carried out with fairness and impartiality, the full accuracy of the data and the reliability of the secondary sources consulted cannot be fully guaranteed. In certain cases, and due to security constraints, a full verification of the facts is still pending. Definition of terms: For the purpose of this report the following terms are used: “Pro-Governmental forces ” includes ISAF, OEF, ANSF (including the Afghan National Army, the Afghan National Police and the National Security Directorate) and the official close protection details of officials of the IRoA. “Anti government elements ” includes Taliban forces and other anti-government elements. “Other causes ” includes killings due to unverified perpetrators, unexploded ordnances and other accounts related to the conflict (including border clashes). “Civilian”: A civilian is any person who is not an active member of the military, the police, or a belligerent group. Members of the NSD or ANP are not considered as civilians. Grand total of civilian casualties for the overall period: The grand total of civilian casualties is 1523 of which: • 700 by Anti government elements. • -

European Union Consolidated Financial Sanctions List

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Service for Foreign Policy Instruments European Union Consolidated Financial Sanctions List This list has been updated on 01/10/2018 16:51 European Union Consolidated Financial Sanctions List Table of contents 1. Introduction3 2. Individuals or persons3 3. Entities or groups349 4. Disclaimer476 Page 2 on 476 European Union Consolidated Financial Sanctions List 1. INTRODUCTION The present document contains the Consolidated List of persons, groups and entities subject to EU Financial Sanctions. The latest version of this file is here. 2. INDIVIDUALS OR PERSONS EU reference number: EU.1787.1 Legal basis: 2017/404 (OJ L63) Programme: AFG - Afghanistan Identity information: • Name/Alias: Saraj Haqani • Name/Alias: Sirajuddin Jallaloudine Haqqani Function: Na’ib Amir (Deputy Commander) • Name/Alias: Siraj Haqqani • Name/Alias: Serajuddin Haqani • Name/Alias: Siraj Haqani • Name/Alias: Khalifa Birth information: • Birth date: Circa from 1977 to 1978 Birth place: Afghanistan, Khost province • Birth date: Circa from 1977 to 1978 Birth place: Pakistan, Danda, Miramshah, North Waziristan • Birth date: Circa from 1977 to 1978 Birth place: Afghanistan, Srana village, Garda Saray district, Paktia province • Birth date: Circa from 1977 to 1978 Birth place: Afghanistan, Neka district, Paktika province Citizenship information: • Citizenship: Afghanistan Contact information: • Address: Pakistan, Miramshah, North Waziristan, Manba’ul uloom Madrasa • Address: Pakistan, Miramshah, North Waziristan, Kela neighbourhood/Danda neighbourhood • Address: Pakistan, Miramshah, North Waziristan, Dergey Manday Madrasa Remark: Heading the Haqqani Network as of late 2012. Son of Jalaluddin Haqqani. Belongs to Sultan Khel section, Zadran tribe of Garda Saray of Paktia province, Afghanistan. Believed to be in the Afghanistan/ Pakistan border area. -

THE ANSO REPORT -Not for Copy Or Sale

The Afghanistan NGO Safety Office Issue: 10 September 1st to 15th 2008 ANSO and our donors accept no liability for the results of any activity conducted or omitted on the basis of this report. THE ANSO REPORT -Not for copy or sale- Inside this Issue COUNTRY SUMMARY Central Region 2 While the overall suicide at- 5 SUICIDE ATTACKS (Country Cumulative Totals) Northern Region tack volumes are down 25 Eastern Region 6 (30%) this year in compari- son to 2007, changes in the 20 Western Region 9 methods of deployment, tar- 15 Southern Region 10 geting patterns, as well as efficacy, have all been wit- 10 13 ANSO Info Page nessed in relation to such 5 attacks reported this year. The efficacy of suicide at- 0 tacks in regards to casualty JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG YOU NEED TO KNOW yields has increased, primarily 2006 2007 2008 due to the chosen target sites • Increased frequency of (as in the Indian Embassy BBIED attacks in popula- tack vectors. Using a com- seen most commonly in tion centers and “dog fight” bombings in bination of small arms fire the Eastern and Southern Kabul and Kandahar) and and/or multiple bombers Regions, allow follow on • Prevalence of AOG the resultant high civilian against high profile GoA attackers to gain access checkpoints along main casualties. and security force installa- into the facility itself, caus- roads In regards to deployment tions, AOG have attempted ing a greater casualty yield • Prevailing abduction/ patterns, suicide attacks are to increase the likelihood of in the target population. -

Gunmen Kill Five Female Afghan Airport Staff in Kandahar

2 Main News Page Sharbat Gula Case: Gunmen Kill Five Female Afghan NADRA Officials Freed on Bail PESHAWAR - Two former officials of the Airport Staff in Kandahar National Database and Registration Au- KANDAHAR - Five female Afghan and had been hired by a private secu- thority (NADRA), accused of issuing the guards working in the airport in south- rity company. “Two gunmen on mo- Pakistani Computerised National Iden- ern Kandahar were killed by unknown torbike followed their van and opened tity Card (CNIC) to National Geographic’s gunmen as they were on their way to fire on them, killing the five and their famed ‘Afghan Girl’, Sharbat Gula, have work, security officials said on Sat- driver this morning, said Samim. been granted bail. urday, the latest in a string of attacks No group has claimed responsibility Peshawar High Court judge Justice Yahya against women in Afghanistan. for Saturday’s attack but the Taliban in- Afridi ordered the release of Emad Khan From bomb attacks to targeted or hon- surgents waging an insurgency to top- and Mohsin Ehsan on bail on Friday after or killings or domestic abuses, Afghan ple the foreign-backed government of hearing arguments from the defence coun- women have borne the brunt of the 15 President Ashraf Ghani oppose wom- sel and the Federal Investigation Agency years of conflicts during the Taliban- en working outside their homes. (FIA) lawyer. led insurgency as security has dete- Although Afghan women had made The pre-arrest bail of another ex-official riorated and violence has increased in hard-fought rights gains in education of NADRA, Palwasha Afridi, has already most parts of the country.