Gendered Mission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Part III - Administrative, Procedural, and Miscellaneous

Part III - Administrative, Procedural, and Miscellaneous Determination of Housing Cost Amounts Eligible for Exclusion or Deduction for 2010 Notice 2010-27 SECTION 1. PURPOSE This notice provides adjustments to the limitation on housing expenses for purposes of section 911 of the Internal Revenue Code (Code) for specific locations for 2010. These adjustments are made on the basis of geographic differences in housing costs relative to housing costs in the United States. SECTION 2. BACKGROUND Section 911(a) of the Code allows a qualified individual to elect to exclude from gross income the foreign earned income and housing cost amount of such individual. Section 911(c)(1) defines the term “housing cost amount” as an amount equal to the excess of (A) the housing expenses of an individual for the taxable year to the extent such expenses do not exceed the amount determined under section 911(c)(2), over (B) 16 percent of the exclusion amount (computed on a daily basis) in effect under section 911(b)(2)(D) for the calendar year in which such taxable year begins ($250.68 per day for 2010, or $91,500 for the full year), multiplied by the number of days of that taxable year within the applicable period described in section 911(d)(1). The applicable period is the period during which the individual meets the tax home requirement of section 911(d)(1) and either the bona fide residence requirement of section 911(d)(1)(A) or the physical presence requirement of section 911(d)(1)(B). Assuming that the entire taxable year of a qualified individual is within the applicable period, the section 911(c)(1)(B) amount for 2010 is $14,640 ($91,500 x .16). -

National Administrative Department of Statistics

NATIONAL ADMINISTRATIVE DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS Methodology for the Codification of the Political- Administrative Division of Colombia -DIVIPOLA- 0 NATIONAL ADMINISTRATIVE DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS JORGE BUSTAMANTE ROLDÁN Director CHRISTIAN JARAMILLO HERRERA Deputy Director MARIO CHAMIE MAZZILLO General Secretary Technical Directors NELCY ARAQUE GARCIA Regulation, Planning, Standardization and Normalization EDUARDO EFRAÍN FREIRE DELGADO Methodology and Statistical Production LILIANA ACEVEDO ARENAS Census and Demography MIGUEL ÁNGEL CÁRDENAS CONTRERAS Geostatistics ANA VICTORIA VEGA ACEVEDO Synthesis and National Accounts CAROLINA GUTIÉRREZ HERNÁNDEZ Diffusion, Marketing and Statistical Culture National Administrative Department of Statistics – DANE MIGUEL ÁNGEL CÁRDENAS CONTRERAS Geostatistics Division Geostatistical Research and Development Coordination (DIG) DANE Cesar Alberto Maldonado Maya Olga Marina López Salinas Proofreading in Spanish: Alba Lucía Núñez Benítez Translation: Juan Belisario González Sánchez Proofreading in English: Ximena Díaz Gómez CONTENTS Page PRESENTATION 6 INTRODUCTION 7 1. BACKGROUND 8 1.1. Evolution of the Political-Administrative Division of Colombia 8 1.2. Evolution of the Codification of the Political-Administrative Division of Colombia 12 2. DESIGN OF DIVIPOLA 15 2.1. Thematic/methodological design 15 2.1.1. Information needs 15 2.1.2. Objectives 15 2.1.3. Scope 15 2.1.4. Reference framework 16 2.1.5. Nomenclatures and Classifications used 22 2.1.6. Methodology 24 2.2 DIVIPOLA elaboration design 27 2.2.1. Collection or compilation of information 28 2.3. IT Design 28 2.3.1. DIVIPOLA Administration Module 28 2.4. Design of Quality Control Methods and Mechanisms 32 2.4.1. Quality Control Mechanism 32 2.5. Products Delivery and Diffusion 33 2.5.1. -

Redalyc.Islas De Tierra Firme: ¿Un Modelo Para El Caribe Continental

Memorias. Revista Digital de Historia y Arqueología desde el Caribe E-ISSN: 1794-8886 [email protected] Universidad del Norte Colombia Shrimpton Masson, Margaret Islas de tierra firme: ¿un modelo para el Caribe continental? El caso de Yucatán Memorias. Revista Digital de Historia y Arqueología desde el Caribe, núm. 25, enero-abril, 2015, pp. 178-208 Universidad del Norte Barranquilla, Colombia Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=85536228008 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto MEMORIAS ! REVISTA DIGITAL DE HISTORIA Y ARQUEOLOGÍA DESDE EL CARIBE COLOMBIANO ! Islas de tierra firme: ¿un modelo para el Caribe continental? El caso de Yucatán Continental Islands: a model for the mainland Caribbean? The case of Yucatan Margaret Shrimpton Masson Doctora en Ciencias Filológicas por la Universidad de La Habana (Cuba); M.Phil. en Estudios Latinoamericanos por la University of Cambridge (UK); BA en Literatura Inglesa y Español por la University of Leeds (UK). Desde 1990 es profesora e investigadora en el área de Literatura Latinoamericana, de la Facultad de Ciencias Antropológicas de la Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán (Mexico). [email protected] ! Agradecimientos La elaboración de este artículo fue posible gracias a dos instancias: una, con el doble apoyo institucional de la Facultad de Ciencias Antropológicas de la Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán (programa PIFI 2012-13), y el Instituto José María Luís Mora para realizar una estancia de investigación breve en el marco del proyecto “Fronteras en Vilo”, de la Dra. -

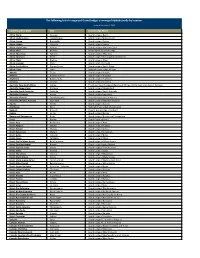

The Following List of Recognized Grand Lodges Is Arranged Alphabetically by Location

The following list of recognized Grand Lodges is arranged alphabetically by location. Updated December 3, 2020 Country and/or State City Grand Lodge Name Africa: Benin Cotonou Grand Lodge of Benin Africa: Burkina Faso Ouagadougou Grand Lodge of Burkina Faso Africa: Congo Brazzaville Grand Lodge of Congo Africa: Gabon Libreville Grand Lodge of Gabon Africa: Ivory Coast Abidjan Grand Lodge of the Ivory Coast Africa: Mali Bamako Malian National Grand Lodge Africa: Mauritius Tamarin Grand Lodge of Mauritius Africa: Morocco Rabat Grand Lodge of the Kingdom of Morocco Africa: Niger Niamey Grand Lodge of Niger Africa: Senegal Dakar Grand Lodge of Senegal Africa: South Africa Orange Grove Grand Lodge of South Africa Africa: Togo Lome National Grand Lodge of Togo Albania Tirana Grand Lodge of Albania Andorra Andorra la Vella Grand Lodge of Andorra Argentina Buenos Aires Grand Lodge of Argentina Armenia Yerevan Grand Lodge of Armenia Australia: New South Wales Sydney The United Grand Lodge of New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory Australia: Queensland Brisbane Grand Lodge of Queensland Australia: South Australia Adelaide Grand Lodge of South Australia Australia: Tasmania Hobart Grand Lodge of Tasmania Australia: Victoria East Melbourne United Grand Lodge of Victoria Australia: Western Australia East Perth Grand Lodge of Western Australia Austria Vienna Grand Lodge of Austria Azerbaijan Baku National Grand Lodge of Azerbaijan Belgium Brussels Regular Grand Lodge of Belgium Bolivia La Paz Grand Lodge of Bolivia Bosnia and Herzegovina -

Atlantico (Baranoa. Barranquilla, Campo De La Cruz, Galapa, Juan De

ATLANTICO (BARANOA. BARRANQUILLA, CAMPO DE LA CRUZ, GALAPA, JUAN DE ACOSTA, MALAMBO, PALMAR DE VARELA, PONEDERA, PUERTO COLOMBIA, SABANAGRANDE, SOLEDAD, SUAN, TUBARA) Departamento Municipio Solicitud Dirección ATLANTICO BARANOA SOL0000001985 VÃa Cordialidad Km 96 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000222 Calle 72 # 38-79 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000232 Calle 84 # 59-34 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000203 Calle 61 entre carreras 34 y 35 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000255 Calle 34 con carrera 45 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000236 Calle 110 # 31 - 15 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000231 Vía 40 # 73-290 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000254 Calle 70 con carrera 46 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000244 Calle 98 # 56-162 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000226 Carrera 51B # 79-192 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000250 Calle 82B # 26C1 - 60 (casa esquina) ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000225 Carrera 51B - Calle 102 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000228 Calle 19 entre carreras 3D(Boulevard) ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000239 Calle 110# 10 - 427 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000204 Calle 76 # 38C - 110 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000223 Calle 56 # 14 - 24 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000224 Calle 45 # 1Sur - 39 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000240 Carrera 6 - Calle 72 / carrera 56 # 65-44 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000245 Carrera 21 # 78-44 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000221 Calle 30 # 4B-350 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000233 Calle 45 # 21-39 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000235 Calle 45 # 21 - 18 ATLANTICO BARRANQUILLA SOL0000000230 -

Modelo De Desarrollo Integral De Comunidades Sostenibles De La Fundación Mario Santo Domingo En Villas De San Pablo, Barranquilla

capulo 2 Estudio de caso: Modelo de desarrollo integral de comunidades sostenibles de la Fundación Mario Santo Domingo en Villas de San Pablo, Barranquilla Elaborado por: Lina María Valencia Ocampo, estudiante de la Maestría en Responsabiliad Social y Sostenibilidad. Dirigido por: Óscar Iván Pérez, docente-investigador Maestría en Responsabilidad Social y Sostenibilidad. Se agradece, de manera especial, el acompañamiento de Ronald Silva Manjarrés, director Unidad Gestión del Conocimiento y de Anahel Hernández Valega, coordinadora Unidad Gestión del Conocimiento, por su apoyo en el proceso de sistematización del presente caso. inroduccin La Fundación Mario Santo Domingo, FMSD, es una organización sin ánimo de lucro que pertenece al grupo familiar empresarial colombiano Santo Do- mingo, con 55 años de operación en el territorio colombiano, especialmente en la Región Caribe. En la actualidad, la FMSD tiene la Dirección General en la ciudad de Bogotá, con seccionales en Barranquilla (Atlántico) y Cartagena (Bolívar) y en su estructura organizacional cuenta con un equipo de 170 colaboradores directos, quienes apoyan las unidades estratégicas, misionales y de soporte de la organización (FMSD, 2015). Con base en su trayectoria en el sector de vivienda de interés social y prioritario, en 2009 la FMSD ha consolidado un modelo propio denominado “Desarrollo Integral de Comunidades Sostenibles – DINCS”, con el objetivo de lograr que los proyectos de vivienda trasciendan los temas inmobilia- rios para alcanzar la construcción de comunidades sostenibles, mediante esquemas estructurados de participación, empoderamiento y de liderazgo proactivo. En la actualidad, la FMSD lleva a cabo tres proyectos bajo este modelo en dos ciudades, un proyecto en Barranquilla y dos en Cartagena. -

Conference Proceedings of the 7Th

1 In Giannetti, B.F.; Almeida, C.M.V.B.; Agostinho, F. (editors): Advances in Cleaner Production, Proceedings of the 7th International Workshop, UNIP, Barranquilla, Colombia. June 21st - 22nd, 2018. Conference Proceedings June, 21st to 22nd 2018 Barranquilla, Colombia General Chair and Founder Biagio F. Giannetti – Paulista University (UNIP) - Brazil Directive Committee Juan José Cabello Eras - Conference Chair - Universidad de La Costa - Colombia Zhifeng Yang – Conference Co-Chair - Beijing Normal University - China Consulting Committee Asian and African Director of ACPN: Gengyuan Liu – Beijing Normal University – China European Center Director of ACPN: Ginevra Virginia Lombardi – University of Florence – Italy Latin America and Caribbean Center Director of ACPN: Luís Eduardo Velázquez Contreras – University of Sonora – Mexico North American Center Director of ACPN: Bruno Silvestre – University of Manitoba – Canada Oceanian Director of ACPN - Linda Hancock - Deakin University - Australia 7th Special Volume of the International Workshop: Advances in Cleaner Production Committee Journal of Cleaner Production (JCLP): Cecília M. V. B. Almeida – Paulista University (UNIP) - Brazil Journal of Environmental Accounting and Management (JEAM): Sergio Ulgiati - Parthenipe University of Naples - Italy INGE CUC - Alexis Sagastume Gutierrez - Universidad de La Costa - Colombia Advances in Cleaner Procution Network (ACPN) Committee Feni Agostinho – Committee Coordinator – Paulista University (UNIP) – Brazil “CLEANER PRODUCTION FOR ACHIEVING THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS” Barranquilla – Colombia – June 21st - 22nd - 2018 2 In Giannetti, B.F.; Almeida, C.M.V.B.; Agostinho, F. (editors): Advances in Cleaner Production, Proceedings of the 7th International Workshop, UNIP, Barranquilla, Colombia. June 21st - 22nd, 2018. “CLEANER PRODUCTION FOR ACHIEVING THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS” Barranquilla – Colombia – June 21st - 22nd - 2018 3 In Giannetti, B.F.; Almeida, C.M.V.B.; Agostinho, F. -

Colombia Case Study

United Nations Development Programme GENDER EQUALITY AND WOMEN’S EMPOWERMENT IN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION COLOMBIA CASE STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS KEY FACTS ................................................................................................................................. 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.............................................................................................................. 4 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................ 6 CONTEXT .................................................................................................................................... 7 Socio-economic context ...................................................................................................................... 7 Gender equality context....................................................................................................................... 7 WOMEN’S PARTICIPATION IN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION .................................................10 POLICY REVIEW AND IMPLEMENTATION ISSUES ...............................................................32 Gender equality legislation ............................................................................................................... 32 Public administration legislation and policy ............................................................................... -

Diseño Del Plan De Desarrollo De Cultura Y Turismo Del Municipio De Juan De Acosta

Diseño del Plan de Desarrollo de Cultura y Turismo del Municipio de Juan De Acosta 2019 - 2024 Mariana Fernández Lamadrid Universidad Autónoma Del Caribe Facultad De Ciencias Administrativas, Económicas Y Contables Programa De Administración De Empresas Turísticas Y Hoteleras Barranquilla, Atlántico Diciembre del 2018 Diseño del Plan de Desarrollo de Cultura y Turismo del Municipio de Juan De Acosta 2019 - 2024 Mariana Fernández Lamadrid Tutor: Beatriz Diaz-Solano Trabajo investigativo como opción de grado para optar título de Administrador de Empresas Turísticas y Hoteleras Universidad Autónoma Del Caribe Facultad De Ciencias Administrativas, Económicas Y Contables Programa De Administración De Empresas Turísticas Y Hoteleras Trabajo De Grado IX Semestre Barranquilla, Atlántico 2018 iii Tabla de contenido Resumen ........................................................................................................................................ ix Presentación................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Planteamiento del Problema ................................................................................................. 3 Pregunta Problema ...................................................................................................................... 4 2. Objetivos ................................................................................................................................. 5 2.1. Objetivo General ............................................................................................................. -

Tabla De Municipios

NOMBRE_DEPTO PROVINCIA CODIGO_MUNICIPIO NOMBRE_MPIO Nombre Total 91263 EL ENCANTO El Encanto 91405 LA CHORRERA La Chorrera 91407 LA PEDRERA La Pedrera 91430 LA VICTORIA La Victoria 91001 LETICIA Leticia AMAZONAS AMAZONAS 91460 MIRITI - PARANÁ Miriti - Paraná 91530 PUERTO ALEGRIA Puerto Alegria 91536 PUERTO ARICA Puerto Arica 91540 PUERTO NARIÑO Puerto Nariño 91669 PUERTO SANTANDER Puerto Santander 91798 TARAPACÁ Tarapacá Total AMAZONAS 11 05120 CÁCERES Cáceres 05154 CAUCASIA Caucasia 05250 EL BAGRE El Bagre BAJO CAUCA 05495 NECHÍ Nechí 05790 TARAZÁ Tarazá 05895 ZARAGOZA Zaragoza 05142 CARACOLÍ Caracolí 05425 MACEO Maceo 05579 PUERTO BERRiO Puerto Berrio MAGDALENA MEDIO 05585 PUERTO NARE Puerto Nare 05591 PUERTO TRIUNFO Puerto Triunfo 05893 YONDÓ Yondó 05031 AMALFI Amalfi 05040 ANORÍ Anorí 05190 CISNEROS Cisneros 05604 REMEDIOS Remedios 05670 SAN ROQUE San Roque NORDESTE 05690 SANTO DOMINGO Santo Domingo 05736 SEGOVIA Segovia 05858 VEGACHÍ Vegachí 05885 YALÍ Yalí 05890 YOLOMBÓ Yolombó 05038 ANGOSTURA Angostura 05086 BELMIRA Belmira 05107 BRICEÑO Briceño 05134 CAMPAMENTO Campamento 05150 CAROLINA Carolina 05237 DON MATiAS Don Matias 05264 ENTRERRIOS Entrerrios 05310 GÓMEZ PLATA Gómez Plata NORTE 05315 GUADALUPE Guadalupe 05361 ITUANGO Ituango 05647 SAN ANDRÉS San Andrés 05658 SAN JOSÉ DE LA MONTASan José De La Montaña 05664 SAN PEDRO San Pedro 05686 SANTA ROSA de osos Santa Rosa De Osos 05819 TOLEDO Toledo 05854 VALDIVIA Valdivia 05887 YARUMAL Yarumal 05004 ABRIAQUÍ Abriaquí 05044 ANZA Anza 05059 ARMENIA Armenia 05113 BURITICÁ Buriticá -

Barranquilla Y Circunvalar De La Prosperidad Del Atlántico

CUARTA GENERACIÓN DE CONCESIONES Grupo 4 Cartagena – Barranquilla y Circunvalar de la Prosperidad del Atlántico SITUACIÓN ACTUAL SITUACIÓN ACTUAL Tramo 1. Cartagena – Barranquilla SITUACIÓN ACTUAL Tramo 2. Circunvalar de la Prosperidad del Atlántico DESCRIPCIÓN DEL PROYECTO Longitud total 146.7 kilómetros. • Tramo 1. Cartagena – Barranquilla: 110 km. • Tramo 2. Circunvalar de la Prosperidad del Atlántico: 36.7 km. DESCRIPCIÓN DEL PROYECTO Tramo 1. Cartagena - Barranquilla Tramo 1. Cartagena – Barranquilla Sector 1: K 0+000 a K 7+500: Paso por la Ciénaga de La Virgen Sector 2: K 7+500 a K 98+060: Ciénaga de La Virgen – Puerto Colombia Sector 3: K 98+060 a K 110+000: Puerto Colombia - Barranquilla A iniciar una vez el Concesionario actual revierta la concesión a la Nación (fin del año 2019). DESCRIPCIÓN DEL PROYECTO Tramo 1. Cartagena - Barranquilla 0+000 A 7+500 • 0+000 al 7+500: Rehabilitación y mantenimiento de la calzada existente y puentes. • 0+000 al 2+000: Construcción de la segunda calzada. • 2+000 – 7+500 Construcción, operación y mantenimiento de los viaductos del Gran Manglar, la Ye y del Gran Viaducto • 1+225 al 4+434 Construcción y mantenimiento de la vía de servicio de este tramo. DESCRIPCIÓN DEL PROYECTO Tramo 1. Cartagena - Barranquilla 0+000 A 7+500 DESCRIPCIÓN DEL PROYECTO Tramo 1. Cartagena - Barranquilla 0+000 A 7+500 INTERSECCIÓN ELEVADA CIELO MAR DESCRIPCIÓN DEL PROYECTO Tramo 1. Cartagena - Barranquilla 0+000 A 7+500 DESCRIPCIÓN DEL PROYECTO Tramo 1. Cartagena - Barranquilla 7+500 A 98+060 • PR 7+500 al PR 16+000: Operación, mantenimiento de las dos calzadas. -

Global Directory of Catholic Seminaries Part V: South America

Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate Georgetown University Washington, D.C. Global Directory of Catholic Seminaries Part V: South America January 2017 Michal J. Kramarek, Ph.D. Fr. Thomas P. Gaunt, S.J., Ph.D. Santiago Sordo-Palacios Part V: South America Number of Seminary Records for South America in the Directory of Seminaries by Country This part of the Directory of Catholic Seminaries describes seminaries in South America. The map above illustrates the number of seminary records in the Directory by country. Overall, the Directory includes 764 seminary records for South America. Among countries in this world region, the Directory includes the highest number of seminary records for Brazil (303 seminaries), Colombia (152 seminaries), and Peru (107 seminaries). 2 Comparison between the Number of Seminaries in the Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae (ASE) and Its Equivalent in the Directory of Catholic Seminaries (DCS) in South America by Country1 Number of seminaries in ASE Number of seminaries in DCS Secondary Philosophy and Not ASE Secondary Philosophy and Not DCS schools theology classified total schools theology classified total Argentina 35 89 - 124 1 28 30 59 Bolivia 28 25 - 53 3 19 1 23 Brazil 460 550 - 1,010 14 154 135 303 Chile 11 59 - 70 0 25 6 31 Colombia 100 177 - 277 3 103 46 152 Ecuador 30 43 - 73 0 34 16 50 Falkland 0 0 - 0 0 0 0 0 Islands French Guiana 0 0 - 0 0 0 0 0 Guyana 0 0 - 0 0 0 0 0 Paraguay 26 23 - 49 1 5 1 7 Peru 62 90 - 152 7 80 20 107 Suriname 0 2 - 2 0 0 0 0 Uruguay 4 3 - 7 0 3 0 3 Venezuela 29 64 - 93 2 17 2 21 South America 785 1,125 0 1,910 31 468 257 756 The table above attempts to estimate how complete the Directory is by comparing the number of seminaries listed in the Segreteria di Stato Vaticano's (2013) Annuarium Statisticum Ecclesiae with the number of open seminaries included in this Directory.