Download (2586Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cmlc Annual Report 2013 Contents

CMLC Annual Report // 2013 CHA1 RAC TER CMLC ANNUAL REPORT 2013 CONTENTS A Message from Lyle Edwards 8 A Message from Michael Brown 10 A Message from Mayor Naheed Nenshi 12 Public Infrastructure Projects 13 Infrastructure Updates 14 Heritage Buildings 16 Ongoing Projects 17 Community Infrastructure Partners 22 Marketing, Public Engagement and Communications 26 Environment and Sustainability 36 Accountability Report 40 Independent Auditor’s Report 49 Financial Statements 51 Notes to Financial Statements 57 CMLC Team 70 CMLC staff showed their true colours true in their unscripted, far-beyond-the-call- of-duty efforts to CHA evacuate, comfort and return home some of RAC the neighbourhood’s TER most vulnerable residents. In a year forever marked by the June 2013 flood event, the residents and developers of East Village showed a strength and generosity that isn’t apparent in everyday life. When the long-standing homes of East Village seniors – Murdoch Manor, King Tower and East Village Place – were compromised by rising waters, CMLC staff showed their true colours in their unscripted, far-beyond-the-call-of-duty participation in efforts to evacuate, comfort and return home some of the neighbourhood’s most vulnerable residents. The infrastructure of East Village proved resilient in 2013 because the flood plain has been raised up to six feet in some places since 2007. But it’s the resiliency and character of the people – residents, business owners, CMLC staff, the East Village Neighbourhood Association and many others – that we remember long after the waters receded. CMLC’s hybrid retail strategy, designed to attract both destination and niche retailers, drew the country’s largest real estate trust and the city’s most enterprising culinary entrepreneurs. -

Calgary's Dynamic Dance Scene P. 15

Enough $$ for YYC music? The Calgary PAGE 19 JOURNALReporting on the people, issues and events that shape our city APRIL 2015 FREE Calgary’s Dynamic Dance Scene P. 15 Trespassing in Medicinal Flying paint elder care homes marijuana A night at Calgary’s only Law being questioned by Calgary’s first medicinal indoor paintball field loved ones of seniors marijuana clinic to open PAGE 4-5 PAGE 6-7 PAGE 28 THIS ISSUE APRIL 2015 FEATURES EDITORS-IN-CHIEF CAITLIN CLOW OLIVIA CONDON CITY EDITORS JOCELYN DOLL JALINE PANKRATZ ARTS EDITORS ALI HARDSTAFF ANUP DHALIWAL CITY FEATURES EDITOR PAUL BROOKS Spring into the SPORTS EDITOR A.J. MIKE SMITH April Journal and come with us to SPORTS PHOTO & PRODUCTION EDITORS some of our MASHA SCHEELE favourite “places.” GABRIELA CASTRO FACULTY EDITORS TERRY FIELD FEATURES PH: (403) 440-6189 [email protected] THE LENS SALLY HANEY PH: (403) 462-9086 [email protected] PRODUCTION SUPERVISOR ADVERTISING BRAD SIMM PH: (403) 440-6946 [email protected] The Calgary Journal reports on the people, issues and events that shape our city. It is produced by journalism students at Mount Royal University. CITY THE LENS PAGE 4 | Trespassing on seniors’ facilities PAGE 16 | Growing dance scene FOLLOW US ONLINE: PAGE 6 | Calgary’s first marijuana clinic @calgaryjournal PAGE 8 | Babyboomers facing homelessness facebook.com/CalgaryJournal ARTS calgaryjournal.ca PAGE 9 | April is poetry month PAGE 20 | Vinyl pressing PAGE 21 | Local bands leaving town for success CONTACT THE JOURNAL: FEATURES PAGE 22 | Funding for artists across Canada -

City-Owned Historic Resource Management Strategy

LAS2014-25 ATTACHMENT 5 HISTORIC BUILDING SNAPSHOTS 1. A.E. Cross House 16. Glenmore Water Treatment Plant 2. Armour Block 17. Grand Trunk Cottage School 3. Bowness Town Hall 18. Hillhurst Cottage School 4. Calgary Public Building 19. Holy Angels School 5. Capitol Hill Cottage School 20. McHugh House 6. Cecil Hotel 21. Merchant’s Bank Building 7. Centennial Planetarium 22. Neilson Block Facade 8. Calgary City Hall 23. North Mount Pleasant School 9. Cliff Bungalow School 24. Reader Rock Garden - Residence 10. Colonel Walker House 25. Rouleau House 11. Eau Claire & Bow River Lumber 26. St.Mary’s Parish Hall/CNR Station 12. Edworthy House 27. Union Cemetery Caretakers Cottage 13. Fire Hall No. 1 28. Union Cemetery Mortuary 14. Fire Hall No. 2 29. Y.W.C.A. 15. Fire Hall No. 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 ISC: UNRESTRICTED Page 1 of 30 LAS2014-25 ATTACHMENT 5 1. A.E. CROSS HOUSE of Calgary's oldest homes and its asymmetrical design features includes several unusual architectural elements typical of the Queen Anne Revival period. These include a wood-shingled hip roof with cross gables, banks of bay windows on the front and side facades, a sandstone foundation, a "widow's walk" balustrade, and gingerbread trim. The interior has many of the original features, including hardwood flooring, fir used for the door and window trim as well as an elaborate open stairway with custom fabricated wood handrails, newels and balusters and two brick fireplaces. -

Tees Valley Combined Authority Agenda

Tees Valley Combined Authority Agenda www.stockton.gov.uk Date: Monday, 4th April, 2016 at 11.00am Venue: The Curve, Teesside University, Middlesbrough, TS1 3BA Membership: Councillor Bill Dixon (Leader of Darlington Borough Council) Councillor Christopher Akers-Belcher (Leader of Hartlepool Council) Mayor David Budd (Mayor of Middlesbrough Council) Councillor Sue Jeffrey (Leader of Redcar and Cleveland Borough Council) Councillor Bob Cook (Leader of Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council) Paul Booth (Chair of Tees Valley Local Enterprise Partnership) Associate Membership: Phil Cook (Member of Tees Valley Local Enterprise Partnership) Paul Croney(Member of Tees Valley Local Enterprise Partnership) Ian Kinnery (Member of Tees Valley Local Enterprise Partnership) Alastair MacColl (Member of Tees Valley Local Enterprise Partnership) Naz Parkar (Member of Tees Valley Local Enterprise Partnership) Nigel Perry (Member of Tees Valley Local Enterprise Partnership) David Robinson (Member of Tees Valley Local Enterprise Partnership) David Soley (Member of Tees Valley Local Enterprise Partnership) Alison Thain (Member of Tees Valley Local Enterprise Partnership) AGENDA 1. Confirmation of Membership:- 1. To note the constituent Tees Valley Council Members appointed to the Tees Valley Combined Authority 2. To agree the nomination from the Tees Valley Local Enterprise Partnership (The Chair of the Tees Valley Local Enterprise Partnership) 3. To agree the Associate Membership of the Tees Valley Combined Authority 2. Appointment of Chair To appoint a Chair for the period up until the date of the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Tees Valley Combined Authority 1 Tees Valley Combined Authority Agenda www.stockton.gov.uk 3. Apologies for absence 4. Appointment of Vice Chair To appoint a Vice Chair for the period up until the date of the 2016 Annual Meeting of the Tees Valley Combined Authority 5. -

National Historic Sites of Canada System Plan Will Provide Even Greater Opportunities for Canadians to Understand and Celebrate Our National Heritage

PROUDLY BRINGING YOU CANADA AT ITS BEST National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Parks Parcs Canada Canada 2 6 5 Identification of images on the front cover photo montage: 1 1. Lower Fort Garry 4 2. Inuksuk 3. Portia White 3 4. John McCrae 5. Jeanne Mance 6. Old Town Lunenburg © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, (2000) ISBN: 0-662-29189-1 Cat: R64-234/2000E Cette publication est aussi disponible en français www.parkscanada.pch.gc.ca National Historic Sites of Canada S YSTEM P LAN Foreword Canadians take great pride in the people, places and events that shape our history and identify our country. We are inspired by the bravery of our soldiers at Normandy and moved by the words of John McCrae’s "In Flanders Fields." We are amazed at the vision of Louis-Joseph Papineau and Sir Wilfrid Laurier. We are enchanted by the paintings of Emily Carr and the writings of Lucy Maud Montgomery. We look back in awe at the wisdom of Sir John A. Macdonald and Sir George-Étienne Cartier. We are moved to tears of joy by the humour of Stephen Leacock and tears of gratitude for the courage of Tecumseh. We hold in high regard the determination of Emily Murphy and Rev. Josiah Henson to overcome obstacles which stood in the way of their dreams. We give thanks for the work of the Victorian Order of Nurses and those who organ- ized the Underground Railroad. We think of those who suffered and died at Grosse Île in the dream of reaching a new home. -

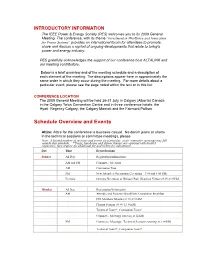

Schedule Overview and Events

INTRODUCTORY INFORMATION The IEEE Power & Energy Society (PES) welcomes you to its 2009 General Meeting. The conference, with its theme “Investment in Workforce and Innovation for Power Systems” provides an international forum for attendees to promote, share and discuss a myriad of ongoing developments that relate to today's power and energy industry. PES gratefully acknowledges the support of our conference host ALTALINK and our meeting contributors. Below is a brief overview and of the meeting schedule and a description of each element of the meeting. The descriptions appear here in approximately the same order in which they occur during the meeting. For more details about a particular event, please see the page noted within the text or in this list: CONFERENCE LOCATION The 2009 General Meeting will be held 26-31 July in Calgary (Alberta) Canada in the Calgary Telus Convention Centre and in three conference hotels: the Hyatt Regency Calgary, the Calgary Marriott and the Fairmont Palliser.. Schedule Overview and Events Attire: Attire for the conference is business casual. No denim jeans or shorts in the technical sessions or committee meetings, please. Note: A limited number of sessions and events (in particular, some committee meeting) may fall outside this schedule. *Tours, luncheons and dinner theater are optional with limited capacities; they require an additional fee and tickets for admittance. Day Time Event/Sessions Sunday All Day Registration/Information AM and PM Committee Meetings AM Companion Tour PM New Attendees Orientation -

Doing Together What We Can't Do Alone

DOING TOGETHER WHAT WE CAN’T DO ALONE Inglewood Bird Sanctuary Science School Chevron Canada officially launches Chevron Open Minds School Program and contributes $1,000,000 over 5 years to help students learn in hands-on environments at the Calgary Zoo, Glenbow Museum and Calgary Science Centre. DON HA R E V Science Centre pilot classes are introduced at D N I E D K Science School (1997-present). Funded by Chevron Canada. Y O K R C Library School Jube School Tinker School Strong Kids School Jube School Library School Seed School N A A Canada Olympic Park (Winsport) Campus L A L I E G L G Calgary classes are introduced (1997-2012). A L I N R A Five new pilots were introduced to Campus Calgary: G Y Leighton Arts Centre pilots Campus Calgary (2007). Z Funded by TransAlta, CODA and RBC Foundation. O O The Calgary Public Library - Library School Inglewood Bird Sanctuary joins Campus Calgary as Bird Aero Space Museum City of Calgary, Calgary Parks pilots Campus Calgary at School and Nature School (1997-2013). Reader Rock Garden (2007, 2012-2013). Aero Space Museum (Hangar Flight Museum) launches Funded by City of Calgary, Calgary Parks. The Mustard Seed - Seed School In partnership with the Calgary Zoo, a forward thinking Funded by Petro-Canada/Suncor. Canada Olympic Park Campus Calgary Aero Space School (2005-2017). Funded by City Healthy Living School Healthy Living School educator (Gillian Kydd, Calgary Board of Education), a University of Calgary classes are offered (1997-2017). Centre for Performing Arts joins Campus Calgary (1999-2001). -

Michael Lembke B.Arch.Sc., PL

Entuitive | Calgary + Lethbridge + Toronto Michael Lembke B.Arch.Sc., P.L. (Eng.), LEED® AP PRINCIPAL - BUILDING ENVELOPE SPECIALIST Michael is co-leader of Entuitive’s overall building envelope services teamgroup, while managing the building envelope group locally in the Calgary office. His expertise includes the design and construction of building envelope systems for new buildings, and restoration of existing buildings and heritage buildings. Michael has over 14 years’ experience in building envelope consulting on projects throughout Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom, including the commercial, residential, healthcare, institutional, sports, residential, healthcare, cultural and retail sectors. Education Michael is recognized by his clients as a dynamic leader who Bachelor of Architectural Science provides sound, progressive insight to help develop and achieve (Building Science), Ryerson University sustainable, building envelope solutions. He thrives in a team Memberships atmosphere, where close collaboration with clients and the design Association of Professional Engineers team results in solutions that equally benefit the project, client and and Geoscientists of Alberta (APEGA) end user. Association of Professional Engineers & Geoscientists of Saskatchewan (APEGS) Alberta Building Envelope Council (ABEC) – Executive Board Member “ ON EACH OF OUR PROJECTS, WE APPLY SOUND PROVEN BUILDING ENVELOPE SCIENCE THEORY, PRACTICAL EXPERIENCE AND NEW TECHNOLOGY IN ORDER TO DELIVER SUSTAINABLE, CONSTRUCTIBLE, AND EFFICIENT SOLUTIONS -

COMPANION/LEISURE ACTIVITIES Access to the Activities Described Below Is Limited to Registered Companions and Registered Children

COMPANION/LEISURE ACTIVITIES Access to the activities described below is limited to registered companions and registered children. Registered companions are invited to mingle and relax in the Companion Hospitality Lounge that will be located in the Penthouse at the Palliser Hotel. Complimentary breakfast will be served Monday through Thursday from 7:00-9:30 AM. The lounge will be the gathering point for all companion tours. For those not participating in a tour, a number of fun and interesting short programs and activities will be held in the lounge during the week. Internet service will be available to allow you to keep in touch while away from home. The lounge will be staffed daily for information about tours, local transportation, points of interests/attractions, things to do with children or on your own, shopping and local advice and be a place to relax between activities. Please check on-site for lounge hours. Details of companion activities will be posted in the companion room for reference. A companion's badge is required for admittance. Each child must have a children’s badge and be accompanied by an adult registered companion when in the Lounge. A full program of optional tours and activities has been planned for registered companions. Descriptions for the all day excursions and half-day in-city tours follow in chronological order. Children are welcomed on most of the tours, but must be accompanied by a parent. A companion or children’s badge is required in order to participate. Please visit the registration desk to check availability and purchase tickets All tours will depart from the Palliser hotel. -

Copyright City of Calgary

PREFACE The City of Calgary Archives is a section of the City Clerk's Department. The Archives was established in 1981. The descriptive system currently in use was established in 1991. The Archives Society of Alberta has endorsed the use of the Bureau of Canadian Archivists' Rules for Archival Description as the standard of archival description to be used in Alberta's archival repositories. In acting upon the recommendations of the Society, the City of Calgary Archives will endeavour to use RAD whenever possible and to subsequently adopt new rules as they are announced by the Bureau. The focus of the City of Calgary Archives' descriptive system is the series level and, consequently, RAD has been adapted to meet the descriptive needs of that level. RAD will eventually be used to describe archival records at the fonds level. The City of Calgary Archives creates inventories of records of private agencies and individuals as the basic structural finding aid to private records. Private records include a broad range of material such as office records of elected municipal officials, records of boards and commissions funded in part or wholly by the City of Calgary, records of other organizations which function at the municipal level, as well as personal papers of individuals. All of these records are collected because of their close relationship to the records of the civic government, and are subject to formal donor agreements. The search pattern for information in private records is to translate inquiries into terms of type of activity, to link activity with agencies which are classified according to activity, to peruse the appropriate inventories to identify pertinent record series, and then to locate these series, or parts thereof, through the location register. -

Tees Valley Devolution Deal

Tees Valley Devolution Deal 1 2 Cllr Bob Cook Leader, Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council ……………………………………… Cllr Sue Jeffrey Leader, Redcar and Cleveland Council ……………………………………… Cllr Christopher Akers-Belcher Leader, Hartlepool Borough Council ……………………………………… Mayor Dave Budd Mayor of Middlesbrough ……………………………………… Cllr Bill Dixon Leader, Darlington Borough Council ……………………………………… Paul Booth OBE Chair, Tees Valley Unlimited Local ……………………………………… Enterprise Partnership The Rt.Hon. George Osborne Chancellor of the Exchequer ……………………………………… The Rt. Hon. Greg Clark Secretary of State for Communities and ……………………………………… Local Government Lord O’Neill of Gatley Commercial Secretary to the Treasury ……………………………………… James Wharton Minister for Local Growth and the Northern ……………………………………… Powerhouse 3 4 Summary of the Devolution Deal agreed in principle by the Government and Tees Valley Shadow Combined Authority Leadership Board The Tees Valley Shadow Combined Authority Leadership Board and the Government have agreed in principle a radical devolution of funding powers and responsibilities. A Combined Authority will be created as soon as possible and a directly elected Mayor for Tees Valley will be established from May 2017. The Mayor will work as part of the Combined Authority subject to local democratic scrutiny, and in partnership with business, through Tees Valley Unlimited, the Local Enterprise Partnership for Tees Valley. This agreement will be conditional on the legislative process, agreement by the constituent councils, and formal endorsement by the Tees Valley Combined Authority Leadership Board (which currently exists in shadow form). The deal provides for the transfer of significant powers for employment and skills, transport, planning and investment from central government to the Tees Valley. It paves the way for further devolution over time and for the reform of public services to be led by Tees Valley. -

Middlesbrough Council Statement of Accounts 2019/20

Middlesbrough Council Statement of Accounts 2019/20 Big Weekend Music Festival Middlesbrough – May 2019 Contents 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. NARRATIVE CORE NOTES TO COLLECTION TEESSIDE ANNUAL GLOSSARY REPORT AND FINANCIAL THE FUND PENSION GOVERNANCE OF TERMS WRITTEN STATEMENTS ACCOUNTS FUND STATEMENT STATEMENTS Narrative Movement in Detailed Income and Pension Report Reserves Notes to Expenditure Fund Statement the Account Statement Accounts of Accounts Independent Comprehensive Notes to the Notes to Auditors report Income and Collection the – Expenditure Fund Pension Middlesbrough Statement Fund Council Independent Balance Sheet Auditors report – Teesside Pension Fund Statement of Cash Flow Responsibilities Statement Middlesbrough Council Statement of Responsibilities – Teesside Pension Fund Page 02 Page 29 Page 35 Page 97 Page 101 Page 139 Page 162 The Statement of Accounts for Middlesbrough Council provides an overview of the Council’s financial position at 31 March 2020 and a summary of its income and expenditure during the 2019/2020 financial year. The accounts are, in parts, technical and complex as they have been prepared to comply with the requirements of the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA) as prescribed by the Code of Practice on Local Authority Accounting in the United Kingdom, and International Financial Reporting Standards. The accounts are available on the Council’s website: www.middlesbrough.gov.uk under Statement of Accounts. The Council’s Corporate Affairs and Audit Committee will consider the Accounts for approval on 26 November 2020. The External Auditor’s Report to the Committee will confirm whether the accounts provide a true and fair view of the Council’s financial position and transactions and any issues or amendments made as part of the audit process.