Use of Physical Restraints in Neurosurgery: Guide for a Good Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 13 – Mental Health Table of Contents

To view any policy document as published on the Policy Distribution System click the link on the policy number in the table below. CHAPTER 13 – MENTAL HEALTH TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 13 – MENTAL HEALTH PD/IB/GL NUMBER Seclusion and Restraint in NSW Health Settings PD2020_004 Aggression, Seclusion & Restraint in Mental Health Facilities – Guideline GL2012_005 Focused Upon Older People HEALTHPLAN – Mental Health Services Supporting Plan GL2012_006 Clinical Care of People Who May Be Suicidal PD2016_007 Sexual Safety – Responsibilities and Minimum Requirements for Mental Health PD2013_038 Services Sexual Safety of Mental Health Consumers Guidelines GL2013_012 The NSW Aboriginal Mental Health and Wellbeing Strategy 2020-2025 IB2021_002 NSW Older People’s Mental Health Services SERVICE PLAN 2017-2027 GL2017_022 Specialist Mental Health Services for Older People (SMHSOP) Community GL2017_003 Model of Care Guideline Discharge Planning and Transfer of Care for Consumers of NSW Health Mental PD2019_045 Health Services Drug and Alcohol Psychosocial Interventions Professional Practice Guidelines GL2008_009 Mental Health Clinical Documentation Guidelines GL2014_002 Physical Health Care within Mental Health Services PD2017_033 Physical Health Care for People Living with Mental Health Issues GL2021_006 Psychiatric Malingering – Detection and Management GL2009_016 SAFE START Strategic Policy PD2010_016 SAFE START Guidelines: Improving Mental Health Outcomes for Parents & GL2010_004 Infants School-Link Initiative Memorandum of Understanding PD2010_020 -

Labette Health

LABETTE HEALTH POLICY AND PROCEDURE SUBJECT: RESTRAINT REFERENCE:A/N/SWING BED/ER APPROVED BY: Restraint Committee PAGE 1 OF 10 EFFECTIVE: SEPT/97 REVISED: FEB/JULY99 MAR/01, JAN/02, OCT/03, DEC/03 AUG/05/MAY/07/JULY/08, APR/09, OCT/09, APRIL/12 TITLE: RESTRAINT DEFINITIONS: A restraint is any manual method, physical or mechanical device, material, or equipment that immobilizes or reduces the ability of a patient to move his or her arms, legs, body, or head freely; or a drug or medication when it is used as a restriction to manage the patient’s behavior or restrict the patient’s freedom of movement and is not a standard treatment or dosage for the patient’s condition. Patients Who May Require Restraint 1. Non-violent or non-self destructive patients (Medical): patients who require restraints to prevent removal of tubes, lines, dressings, or to support medical healing or well-being. 2. Violent or self-destructive patients (Behavior): patients who display severely aggressive or destructive behavior that jeopardizes the immediate physical safety of the patient, staff, or others. This category includes patients for which a Dr. Strong might be called. POLICY: 1. It is the intent of Labette Health to be Restraint free. 2. All patients have the right to be free from restraints or seclusion of any form, imposed as a means of coercion, discipline, convenience, or retaliation by staff. 3. Labette Health does not use seclusion as a form of restraint. 4. Restraints shall be used only where alternative methods are not sufficient to protect patients or others from injury. -

Restraint Prevalence Tools

Restraint Prevalence Tools NURSING BEST PRACTICE GUIDELINES EVALUATION USER GUIDE November 2006 Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors. Publication does not imply any endorsement of these views by either of the participating partners of the Nursing Best Practice Research Unit, which include members of the University of Ottawa faculty and members of the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO). 158 Pearl Street / 158, rue Pearl School of Nursing / Toronto ON M5H 1L3 CANADA École des sciences infirmières 451 Smyth 416 599-1925 Ottawa ON K1H 8M5 CANADA 416 599-1926 613 562-5800 (8407) 613 562-5658 http://www.nbpru.ca/ Nursing Best Practice Guidelines Evaluation User Guide Copyright © 2006 by the NBPRU Printed in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada All rights reserved. Reproduction, in whole or in part, of this document without the acknowledgement of the authors and copyright holder is prohibited. The recommended citation is: Davies B, Danseco E, Ploeg J, Heslin, K, Stansfield M, Santos J & Edwards, N. (2006). Nursing Best Practice Guideline Evaluation User Guide: Restraint Prevalence Tools. Nursing Best Practice Research Unit, University of Ottawa, Canada. pp. 1-20. Nursing Best Practice Guidelines Evaluation User Guide Acknowledgements This user guide was based on an evaluation project awarded to Barbara Davies and Nancy Edwards with the Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO) and funded by the Government of Ontario. The authors are grateful for the support of the Nursing Secretariat of the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC), in particular the Chief Nursing Officer, Sue Matthews. The authors would also like to acknowledge the contributions of Tazim Virani and RNAO staff, clinical sites that pilot-tested the evaluation tool, members of the evaluation team and project staff. -

January 18 2017 Regular Meeting

Northern Inyo Hospital January 18 2017 Regular Meeting January 18 2017 Regular Meeting - January 18 2017 Regular Meeting Agenda, January 18 2017 Regular Meeting Agenda, January 18 2017 Regular Meeting...............................................................2 Consent Agenda Financial and Statistical reports, November 2016..................................................18 2013 CMS Validation Survey Monitoring, January 2017 ........................................26 Minutes, December 14 2016 Regular Meeting.........................................................31 Chief of Staff Report Chief of Staff Report, January 2017 .........................................................................40 Med Staff Policy and Procedure Approvals ............................................................41 Healthcare Cost Solutions Backlog Coding Agreement Healthcare Cost Solutions Backlog Coding Agreement......................................109 Nursing Department Policy and Procedure Approvals CNO Policy and Procedure Approvals, January 2017..........................................122 Reach Air/Medical Services Agreement Reach Air/Medical Services Agreement ................................................................134 1 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 2013 CMS Validation Survey Monitoring-January 2017 1. QAPI continues to receive and monitor data related to the previous CMS Validation Survey, including but not limited to, restraints, dietary process measures, case -

M03 01 768 Restraints

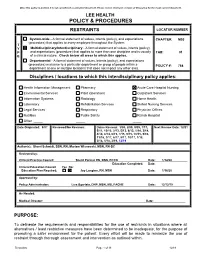

Once this policy is printed, it is not considered a controlled document. Please review electronic version of this policy for the most current document. LEE HEALTH POLICY & PROCEDURES RESTRAINTS LOCATOR NUMBER System-wide - A formal statement of values, intents (policy), and expectations CHAPTER: M03 (procedure) that applies to every employee throughout the System. T Y Multidisciplinary/Interdisciplinary - A formal statement of values, intents (policy), P and expectations (procedure) that applies to more than one discipline and is usually TAB: 01 E of a clinical nature. Check below all areas to which this applies. Departmental - A formal statement of values, intents (policy), and expectations (procedure) exclusive to a particular department or group of people within a POLICY #: 768 department at one or multiple locations that does not impact any other area. Disciplines / locations to which this interdisciplinary policy applies: Health Information Management Pharmacy Acute Care Hospital Nursing Environmental Services Plant Operations Outpatient Services Information Systems Radiology Home Health Laboratory Rehabilitation Services Skilled Nursing Services Legal Services Respiratory Physician Offices Nutrition Public Safety Rehab Hospital Other Date Originated: 9/07 Reviewed/No Revision: Dates Revised: 3/08, 2/09, 9/09, 1/11, Next Review Date: 1/23 5/11, 10/12, 2/13, 5/13, 6/13, 1/14, 3/14, 4/14, 8/14, 6/15, 7/15, 9/15, 10/15, 5/16, 11/16, 3/17, 6/17, 8/17, 10/17, 1/18, 3/18, 5/18, 3/19, 12/19, 10/20, 1/21 Author(s): ; Mariam Wisnewski, MSN, RN-BC Reviewed by: Clinical Practice Council: Monica L. -

Comparing Lay and Professional Perspectives

29th International Nursing Research Congress Paths to Becoming a Nurse Scholar Claudia K Y Lai, PhD, RN, FAAN, FHKCERN, FHKCGN Honorary Professor, School of Nursing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong SAR, China Visiting Professor, Yangzhou University, Yangzhou, China 21 July 2018 Melbourne, Australia A Nursing Faculty Member of Today What is expected of him/her? The Dimensions • An educator? • Teaching – To what extent as an • Research and publication educator? – Which dimension is more • A scholar? important? – How defined? • Leadership, management • A publication machine? and administration • A leader in the • Professional Services profession? • A game changer? Which dimension is the – Play important roles in most or least important? government policies? 2 The Beginning of my Journey … My research questions as a PhD student: • Would the production of a life story book (LSB) as an intervention lead to any changes in the quality of life (QOL- referring to social interactional domain in this study) in residents with dementia in nursing homes? • If it were useful, could its effects be sustained for six weeks after the intervention? Fig 1. Lubinski’s Social breakdown syndrome as applied to communication Fig 2. The Social Breakdown Syndrome as Evidenced by Findings from the Literature Fig 3. Merits of the LSB as an Intervention as suggested by the Literature Modified QOL Dementing disorder Personal helplessness Susceptibility Changing communication skills Provision of activities promoting social QOL Labeling of incompetency (Intervention) Rediscover social & Reduction in communication abilities communication opportunities (remove excess disability) Atrophy of Changed communication communication skills skills (Breaking of of labels) (Breaking Changed social Reduced Awareness of capabilities by of by capabilities staff Awareness engagement skills communication initiatives Fig 4. -

How to Use This Syllabus Look Over the Table of Contents

Annual Mandatory Education—Professional Nurse How to Use this Syllabus Look over the Table of Contents. Note that: o Lessons are organized alphabetically. o Mousing over a Lesson title allows you to left-click and go to that Lesson. o The bottom of each page displays the page number and Lesson title. Exam questions are presented in Lesson order. Hold down the ‘Ctrl’ key while pressing the ‘F’ key to view a ‘Find’ dialog box o Type in a key word or phrase to find it in the text. o Remember that ‘Find’ will find all instances of the word or phrase in the entire document. Before using ‘Find’, consider navigating to the proper Lesson first, in order to be as close as possible to the information you want to ‘Find’. IMPORTANT NOTE on the limitations of this material: This content is not localized to a particular healthcare environment, system, or entity. Since local system and administrative processes are crucial to patient safety, it is imperative that the learner be familiar with local, facility/entity practices such as: policies and procedures, equipment, patient identification and validation procedures, communication and handoff practices, etc. Adhere to your organization’s policies and procedures. How to Use this Syllabus ............................................................................................................................... 1 Abuse ............................................................................................................................................................ 2 Accident Prevention ................................................................................................................................... -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 354 308 CE 062 986 TITLE Nursing

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 354 308 CE 062 986 TITLE Nursing Assistant. Curriculum Guide. Invest in Success. INSTITUTION Idaho State Dept. of Education, Boise. Div. of Vocational Education. REPORT NO Vo-Ed-239 PUB DATE Apr 92 NOTE 251p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC11 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Allied Health Occupations Education; Clinical Experience; Competency Based Education; Curriculum Development; Educational Research; *Home Health Aides; Interpersonal Competence; Job Analysis; Job Performance; *Job Skills; Medical Services; *Nurses Aides; *Nursing; Occupational Information; Postsecondary Education; State Curriculum Guides; State Programs; Statewide Planning; Task Analysis IDENTIFIERS Idaho ABSTRACT Under the Idaho state system for curriculum development in vocational education, Technical Committees madeup solely of industry personnel are responsible for drawingup task lists for each program. Based on a task list specific to the field, this curriculum guide provides the competencies needed by nursing assistants enrolled in postsecondary, short-term vocational education and high school programs. The suggested total completion time for classroom and laboratory work is 60 hours; the amount of clinical time required has been set at 40 hours. Introductory materials include goals of the program, information on competency-based education, and a detailed list of program standards. The curriculum is divided into 10 units. Each unit has the following parts: terminal performance and enabling objectives, -

M03 01 768 Restraints

Once this policy is printed, it is not considered a controlled document. Please review electronic version of this policy for the most current document. LEE HEALTH POLICY & PROCEDURES RESTRAINTS LOCATOR NUMBER System-wide - A formal statement of values, intents (policy), and expectations CHAPTER: M03 (procedure) that applies to every employee throughout the System. T Y Multidisciplinary/Interdisciplinary - A formal statement of values, intents (policy), P and expectations (procedure) that applies to more than one discipline and is usually TAB: 01 E of a clinical nature. Check below all areas to which this applies. Departmental - A formal statement of values, intents (policy), and expectations (procedure) exclusive to a particular department or group of people within a POLICY #: 768 department at one or multiple locations that does not impact any other area. Disciplines / locations to which this interdisciplinary policy applies: Health Information Management Pharmacy Acute Care Hospital Nursing Environmental Services Plant Operations Outpatient Services Information Systems Radiology Home Health Laboratory Rehabilitation Services Skilled Nursing Services Legal Services Respiratory Physician Offices Nutrition Public Safety Rehab Hospital Other Date Originated: 9/07 Reviewed/No Revision: Dates Revised: 3/08, 2/09, 9/09, 1/11, Next Review Date: 12/21 5/11, 10/12, 2/13, 5/13, 6/13, 1/14, 3/14, 4/14, 8/14, 6/15, 7/15, 9/15, 10/15, 5/16, 11/16, 3/17, 6/17, 8/17, 10/17, 1/18, 3/18, 5/18, 3/19, 12/19 Author(s): Sherri Schmidt, BSN, RN; Mariam Wisnewski, -

Proquest Dissertations

u Ottawa l.'Univcrsilc cnnarticnnc Canada's university FACULTE DES ETUDES SUPERIEURES 1=1 FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND ET POSTOCTORALES U Ottawa POSDOCTORAL STUDIES L'Universittf canadicnnc Canada's university Sylvia Ralphs-Thibodeau " AUTEOR DE LA THESE/AW1HOR OF THE'SIS M.Sc. (Epidemiology) GRADE/DEGREE Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine -F-~gg-»g--£g-^ An Examination of the Impact of Ontario's Patient Restraint Minimization Act, 2001 on the Use of Physical and Chemical Restraints Among Elderly Clients in Complex Continuing Care Facilities TITRE DE LA THESE / TITLE OF THESIS Nancy Edwards ______________ _____________ EXAMINATEURS (EXAMINATRICES) DE LA THESE / THESIS EXAMINERS Dean Fergusson __________ Gary W. Slater Le Doyen de la Faculte des etudes superieures et postdoctorales / Dean of the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies An Examination of the Impact of Ontario's Patient Restraint Minimization Act, 2001 on the Use of Physical and Chemical Restraints Among Elderly Clients in Complex Continuing Care Facilities By Sylvia Ralphs-Thibodeau Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in Partial fulfilment of the requirements for the MSc degree in Epidemiology University of Ottawa © Sylvia Ralphs-Thibodeau, Ottawa, Canada, 2007 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-49269-7 -

Relationship Between Nurse Training and Physical Restraints in Nursing Homes Terah Tessier Walden University

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 2016 Relationship between Nurse Training and Physical Restraints in Nursing Homes Terah Tessier Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Health and Medical Administration Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University College of Health Sciences This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Terah Barthany-Harris has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Frazier Beatty, Committee Chairperson, Public Health Faculty Dr. Diana Naser, Committee Member, Public Health Faculty Dr. Namgyal Kyulo, University Reviewer, Public Health Faculty Chief Academic Officer Eric Riedel, Ph.D. Walden University 2016 Abstract Relationship between Nurse Training and Physical Restraints in Nursing Homes by Terah A. Tessier BA, University of Toledo, 1997 MSA, Central Michigan University, 2005 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Health Walden University July 2016 Abstract According to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), approximately 1.3 million U.S. residents are residing in nursing homes. CMS enforced regulations in the Nursing Home Reform Act. -

HA Quality & Risk Management Annual Report (Apr 13

Hospital Authority Quality and Risk Management Annual Report 2013 -2014 (Apr 13 - Mar 14) Acknowledgement This report has comprised the quality and risk management initiatives implemented in the Hospital Authority Head Office (HAHO) and seven clusters in 2013/14. Throughout the years, the HAHO Quality and Safety Division have been working closely with the seven clusters, making relentless effort in key areas under the HA’s strategic direction and service priorities to continuously improve quality and patient safety. We would like to take this opportunity to express our sincere gratitude to all clusters and individuals for their wholehearted dedication and unfailing support to enhance our services. Quality and Safety Division Table of Contents Opening Message 3 Hospital Authority Head Office 4 Hong Kong East Cluster 10 Hong Kong West Cluster 26 Kowloon Central Cluster 36 Kowloon East Cluster 52 Kowloon West Cluster 68 New Territories East Cluster 84 New Territories West Cluster 100 Another year past quickly, and now we have another report. Sometimes I doubt whether we need this yearly report, but as I mentioned last year it is a useful way for us to learn from each other. More recently, I have been asked by the Chairman of the Quality & Safety Subcommittee under the Hospital Governing Committee of Prince of Wales Hospital to provide a summary of what we have done in the last five years and evaluate the impact of those on patient safety. I think that may be another reason to prepare a report. Sometimes we just keep doing things within a moment to reflect. By reflecting on what we have done and their effectiveness, we may be able to identify which areas require more efforts and what should be stopped.