The Rivendell Frame Always Steel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adventure Cyclist GO the DISTANCE

WAYPOINTS 8 MECHANICAL ADVANTAGE 56 OPEN ROAD GALLERY 63 ADVENTURE CYCLIST GO THE DISTANCE. APRIL 2011 WWW.ADVentURecYCLing.ORG $4.95 The Second Annual Cyclists’ Travel Guide INSIDE: 2011 TOURING BIKE BUYEr’s GUIDE | KEEPING THE KIDS HAPPY GPS AND E-MAPPING | THE MIRROR LEGEND SHARE THE JOY GET A CHANCE TO WIN Spread the joy of cycling and get a chance to win cool prizes n For every cyclist you sign up through a gift membersip or who joins through your referral, you score one entry to win a Novara Verita (rei.com/ product/807242) valued at over $1,100. The winner will be drawn from all eligible members in January of 2012. n Recruit the most new members in 2011, and you’ll win a $500 Adventure Cycling shopping spree. n Each month we’ll draw a mini-prize winner who will receive gifts from companies like Old Man Mountain, Cascade Designs, Showers Pass, and others. n The more new members you sign up, the more chances you have to win! Adventure Cycling Association adventurecycling.org/joy Adventure Cycling Corporate Members Adventure Cycling’s business partners play a significant level of support. These corporate membership funds go toward role in the success of our nonprofit organization. Our Corporate special projects and the creation of new programs. To learn more Membership Program is designed to spotlight these key support- about how your business can become a corporate supporter of ers. Corporate Members are companies that believe in what we Adventure Cycling, go to www.adventurecycling.org/corporate or do and wish to provide additional assistance through a higher call (800) 755-2453. -

The Rivendell Reader a Look @ Lugss

$3.50, unless you subscribe T H E R I V E N D E L L R E A D E R Issue No. Issue No. Spring 2004 Spring 2004 32 A Secret Magazine for Bicycle Riders 32 When Song Censors Worried About Louie Louie his year Shimano introduced Saint, a blackish-grey A front derailleur that matches the radius of the smaller big component group for downhill and stunt riding. rings and works well on bikes with low bottom brackets. All Imagine the possibilities if Shimano put its engineers they’d have to do is make a shorter cage and radius it differently. T and weight behind a touring group at the Ultegra This is asking a lot, but: A matching 7-speed indexable bar-end level. Here’s what I’d like to see: shifter would be great. You can tour with STI, but bar-end shifters A 132.5mm rear hub, which would fit in either a 130mm make more sense, and seven rear cogs is plenty for non-racing frame or a 135mm frame. Both sizes have been common for use. The rear wheel would be stronger, and the chain wouldn’t years now, and the proposed group should accommodate either. require a special pin, as the current 9-speed chains do. The in-between 132.5mm-spaced rear hub would do that. If it Current, interbrand-usable bottom brackets. These days were a 130 or 135, no biggie. I think the concept of “splittin’ the Shimano’s top groups come with the bottom brackets that have diff” might not sit well with Shimano’s engineers. -

BUYERS GUIDE 1 a Down Payment on Adventure BUYERS GUIDE 1 a Down Payment on Adventure 2014 Touring Bike Buyer’S Guide by Nick Legan CHUCK HANEYCHUCK BUYERS GUIDE 2

BUYERS GUIDE 1 A Down Payment on Adventure BUYERS GUIDE 1 A Down Payment on Adventure 2014 Touring Bike Buyer’s Guide by Nick Legan CHUCK HANEYCHUCK BUYERS GUIDE 2 dventure — it calls us all. Unfortunately, the short chainstays For those of us who seek it on many mountain bikes often make aboard a bicycle, one of the for pannier/heel interference. Using a most difficult decisions is suspended mountain bike for extend- what machine to take along. ed road touring is overkill in many AIn many cases, a “make-do” attitude instances. works just fine. After all, it’s getting out Likewise, a road touring bike, when in the world that matters most, not the fully loaded, is fairly limited in off-road amount of coin spent on your ride. But scenarios. Although modern tour- if you have the luxury of shopping for ing bikes are certainly strong, riding a new bicycle for your next round of singletrack on a touring bike, though touring adventures, we’re here to help. possible, isn’t as much fun as it is on a We’ve broken this “Touring Bike mountain bike. Buyer’s Guide” down into binary Be honest about where you’re head- decisions. While we hope that all the ed and then read on for specific areas considered content here is appealing, of consideration to help guide your we understand that sometimes it’s im- search. portant to get to the point. Feel free to bounce around the article as your fancy Road machines leads you. With most of the cycling industry It helps to boil decisions down to focused squarely on road racing bikes simple either/or scenarios, but it’s only slightly heavier than a loaf of important to remember that a lot of bread and mountain bikes that put overlap exists among various categories many monster trucks to shame, off-the- of bicycles. -

ADVENTURE CYCLIST- April 2012

COMPANIONS WANTED 7 WAYPOINTS 8 OPEN ROAD GALLERY 47 ADVENTURE CYCLIST GO THE DISTANCE. APRIL 2012 WWW.ADVentURecYCLing.ORG $4.95 BUYEr’s gUIDE: Today’s Touring Bikes PLUS: HOW TO PLAN YOUR TRIP STARTING THE KIDS EARLY IMAGES FROM ABROAD PROFILE: IBF AND BIKE AFRICA 2 ADVENTURE CYCLIST APRIL 2012 ADVENTURECYCLING.ORG ADVENTURE CYCLIST APRIL 2012 ADVENTURECYCLING.ORG 3 4:2012 contents April 2012 · Volume 39 Number 3 · www.adventurecycling.org ADVENTURE CYCLIST is published nine times each year by the Adventure Cycling Association, a nonprofit service organization for recreational bicyclists. Individual membership costs $40 yearly to U.S. addresses and includes a subscrip- tion to Adventure Cyclist and dis- counts on Adventure Cycling maps. The entire contents of Adventure Cyclist are copyrighted by Adventure Cyclist and may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from Adventure Cyclist. All rights reserved. OUR COVER In Mauritania Gostelow rests under the first tree he’d seen for 2,000 miles. Photo by Peter Gostelow. ERIC SCHAMBION (left) In Niger a camel carries more than Amaya Williams. MISSION The mission of Adventure Cycling TOURING BIKE BUYER’S GUIDE by John Wider Association is to inspire people of all 10 What to look for when shopping for your next (or first) touring bike. ages to travel by bicycle. We help cyclists explore the landscapes and history of America for fitness, fun, A TWO-WHEELED GAP YEAR FOR GROWN UPS by Amaya Williams and self-discovery. 16 Ready to plan the extended bike tour you’ve always dreamed of? Here’s how. -

Rivendell Reader RR 42 E Arly 2010

ivendell eader 42 Published erratically ever since 1994 Winter 2010 When Kids had Pea -s hooteRs & s lingshots & P layed MuMblety -Peg eadeR no. 41 Was Mailed in FebRuaRy 2009 and now the name of this phenomenon, but i believe it is one. it’s rare it’s nearly February 2010, and that is why this Reader is to marry the first girl you date, and for the most part that’s a R two Maynards and twice as long. in some ways this issue good thing, although once in a while you should. is rough. in the late ‘70s when i was working at Rei in berkeley, we the Reader has never been entirely about bikes, and that is sold Madshus birkebeiner cross country skis, which at about nothing against bikes at all. i have less against bikes than any - $70 a pair, were the most-expensive light touring skis at the body i know, but there is only so much you can say about them time. they were also the best-looking, with no paint or varnish, in one issue, so some repetition is inevitable. just an oil finish that showed all the wood at its best. google not everybody who starts with us stays with us, anyway, so them and see for yourself. but despite their good looks, or on what’s old to vets is new to rookies. back to “not everybody who top of it, they were great-skiing, high-performance skis, and be - starts with us stays with us”: When you come upon Rivendell fore the age of specialization set in, they were used for every - early in your education as a cycler, there’s a tendency, as you gain thing from groomed track skiing to week-or-two back country experience and knowledge, to explore new territory, discover treks equivalent to a fully loaded off-road bicycle tour. -

How to Buy a Touring Bike

How to Buy aTouring Bike Picking the perfect touring bike for you shouldn’t keep you up at night our decision has been made. The Transamerica Bicycle of finding that model at any one dealership are small, and the odds Route can’t live another year without you, and you need a of finding it in your size are even smaller. Ynew touring bike. It’s not possible to cover all good touring bike options in one Your objective in buying a new touring bike is to drastically issue of a magazine. Our listings remain focused on the tradition- reduce the time spent thinking about it (and its limitations) when al upright touring bike with dropped handlebars. That said, we you’re on your adventure. You want a bike that easily carries your heartily endorse several “ nontraditional” bike choices. A few load, has appropriate gearing for the steepest hills on your route, comments on each: and fits your body dimensions like a well-worn pair of slippers. Tandems. These goals are also compatible with the way most of us use Regular readers of this space know we are big tandem fans at our bikes the other ninety percent of our lives: weekend rides car- Adventure Cycling. Touring on a tandem has interpersonal bene- rying no more than a patch kit, slogging to work on a misty fits you can’t get on a single bike. The short version on picking a November morning, and, if the spirit moves you, training in a tandem for touring: think wide, in both gearing range and tire size. -

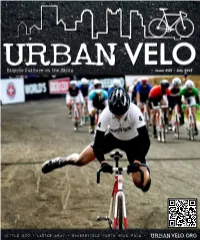

URBAN VELO.ORG Catch Me If You Can

Little 500 • ladies army • bakersfield youth bike polo • URBAN VELO.ORG Catch me if you can... Max bets you can’t. His new ride, the Vector X27H, allows him to “put the pedal to the metal”. Exceptionally strong, speedy, and stylish, it is the perfect partner in crime. Visit www.dahonbikes.com to fi nd your choice among the world’s widest range of folding bicycles. It’s not just a bike – it’s a Dahon. FREE Issue #32 Ju l y 2012 2 koozies with your paid Brad Quartuccio subscription Editor [email protected] Jeff Guerrero Publisher [email protected] On the cover: Bloomington, Indiana’s annual bike race, The Little 500. Read about the 62 year old event on page 30. Photo by Bruce Carver, www.brucecarverphoto.com Co-conspirators: Krista Carlson, Jon Lake, Zachary Woodward, Bruce Carver, Lisa Moffatt, Zack Barowitz, Dan Leto, Andy Singer and Jason Finn Urban Velo, PO Box 9040, Pittsburgh, PA 15224 INCLUDES INTERNATIONAL SUBSCRIPTIONS! Urban Velo is a reflection of the cycling culture in current day cities. Our readers are encouraged to contribute their words and art. Urban Velo is published bi-monthly. That’s six times per year, on the odd months. Issues are available for free down- While supplies last, subscribe to Urban Velo and you’ll receive two load as they become available. Print copies are available koozies in the mail. The koozies come online and at select bicycle retailers and coffee shops. in assorted colors... We choose the colors, but we’ll be sure to send you Bike shops, check out urbanvelo.org/distribution two different ones. -

Whatever Your Price Range, There's a Touring Bike For

Buying a touring bike in 2008 Whatever your price range, there’s a touring bike for you By John Schubert tired and have depleted blood glucose (“the than 10 pounds of baggage (i.e. credit card bonk,” that annoying lack of all energy and touring), you can get by with tires measur- motivation) at the end of a day. Even a strap- ing 700x28C (about 28 mm or 1 1/8 inch ping young athlete can decide that they want wide). Add camping gear and 700x35C (35 to climb a long hill slowly to preserve that mm or 1 3/8 inch) becomes highly desir- blood glucose to last the entire day, the bet- able, although many of us have skimped ter to feel fresh and lively at the beach that by with 700x32C (32 mm or 1 1/4 inch). afternoon and evening. As the roads get rougher or you add more What constitutes wide-range gearing? To camping gear, you want 700x38C, or even a condense many previous magazine articles two-inch mountain bike tire. Many tourists in a few words, you should have a low gear select mountain bikes so they can carry large of no more than 30 gear inches if you’re quantities of gear. riding a bike with little or no baggage on the There are two aspects to tire width: the bike. If you’ll carry camping gear, your low tire that the bike comes with and the maxi- gear should be at most 25 gear inches, and mum tire the bike can fit. -

PBE19 Exhibitor Map And

Exhibitor Booth # Exhibitor Booth # Exhibitor Booth # 44 Bikes 1049 fi’zi:k 1102/1103 rivet cycle works 1093 A Quick Brown Fox T18 Galaxy Gearworks 1033 Rodeo Adventure Labs 1085 ABUS Mobile Security, Inc. 1104 Georgena Terry Bicycles 3006-3 Rolf Prima 1064 Aero Tech Designs 1097 Giordana Custom 2004 Root Ball Bikes 1032 AeroAthletics. LLC 2007 goodr 2015 Rotor Bike Components 1028/1029 Albabici T16 Green Mountain Energy 1100 Royal H Cycles 1044 Alizeti 3001-2 Growler Performance Bikes 2031/2032 Ruchama Yoga T07 ABEA 2009 Guerciotti USA 1098 Savile Road - The Tailored 3008 ADA Tour de Cure T20 Hanford Cycles 2039 Bicycle Apothecary Muse T03 Haro Bicycles 3002 Schwalbe Tires 2013/2014 Astral Cycling 1064 Hawk Racing 1041 Schön Studio 3003 Batch Bicycles 2036 Highway Two 1102/1103 Screen Specialty Shop 1065 Beardman Bicycles 1062 Hill Killer 1053 Selle Anatomica 1052 Beat The Pro Challenge T21 Hiplok 1078 Selle Royal 1102/1103 Befitting Bicycles 1094 HoeferCycles 1006 Selle San Marco 2018 Bern Helmets 2022/TR1 Hollingsworth Frames 1044 Selle SMP T17 Bicycle Club of Philadelphia 2025/2026 Industry Nine 1025/1026 SENA 1027/1040 Bicycle Coalition of Greater Interloc Design Group 1050 Shimano STEPS 2037/2038 1091 Philadelphia Jamis Bicycles 1038 SILCA 1056 Bicycle Paintings 1054 Jeff Velo Art 1081 Skillion 1074 BikeCAD T05 Keating Wheel Company 1033 SKS-Germany 1071 BikeFlights.com 1023 Keystone Bicycle Co. T06 Soma Fabrications 1050 Bikeout T09 Kinekt Active Suspension seat Spa Sport 2008 1082 Bilenky Cycle Works 3006-1 posts Speedplay 1011 -

Touring Bike Buyers' Guide by John Schubert

Touring Bike Buyers’ Guide by John Schubert What to Look for in a Touring Bike High Handlebars Handlebars should be level or up to two inches higher or most of us on our daily rides, than the saddle. High Spoke Count the bike is a flamboyant compan- Conventionally-spoked ion. You stand on the pedals and wheels with a high spoke feel it sprint underneath you. You count are more forgiving Flean into a corner and feel its reassuring and easier to repair. steering geometry. You surge up a hill, and the bike is an eager partner. You see a pot- Frame Construction hole, you jump the bike over the pothole, A touring frame should be all and all is well. metal with a thick top tube. When you add a sizable amount of tour- ing gear, the relationship changes. The bike is still there, but it’s less flamboyant. Loaded with panniers, it’s more like a slow-moving workhorse. It corners a bit more slowly (but still with that reassuring Tire Clearance feeling) because you’re riding more slowly. Ample room for mounting It laughs if you try to sprint or climb fenders make rainy days quickly. And you can forget about jumping more pleasant. potholes. But the bike stays with you for thousands of miles. The same bike can have both those personalities. A good touring Front Mounts bike will be your spry fun-rid- for racks and fenders. ing around-home bike and your Rear Mounts uncomplaining pack mule on an for racks and fenders. extended adventure. -

2009 Rivendell Bicycle Catalog

FOREWORD ATTENTION In 1994 you didn’t have to be a keen seer to predict a dim future for lugged steel frames. There’s a pervading notion among new riders, and even some experienced ones, that carbon fiber RIVENDELL racing bikes are the gold standard of bicycles, the epitome of the craft. But look more closely at An escalating obsession with speed, racing, and new technology was tightening its grips them and you’ll see more technology, less craft. Generalizations are unfair to the exceptions, and on bicycles, and the lugged steel frame, an icon of the past, headed the hit list. But for BICYCLES there are certainly craftsmen working with carbon fiber who put as much effort into their medium fifteen years we’ve played a minor role in the continued existence of not only lugged as torch-bearers heating steel put into theirs. steel frames, but many of the smart parts, accessories and styles of the past that needed for But in the case of carbon fiber, the nature of the material and the relatively short learning curve & continue to need a cheerleader to survive. Some have died despite our efforts, some limits the “craft” without redefining the word. High prices and race wins explain its popularity, but have thrived partly or largely because of them, but new buds appear each year, and their when the dust settles, a carbon fiber bicycle frame is still a carbon fiber bicycle frame, and that’s not necessarily good. Carbon is light, for instant mass appeal. It is theoretically strong, but if the future isn’t exactly bright, but it’s no longer dim. -

The Rivendell Reader Good Things Review

If you get this free at a shop or event and you like it, please subscribe. Four times per year, $20/year or $35/3years. Call 1 (800) 345-3918. T H E R I V E N D E L L R E A D E R Issue No. Issue No. 31 January 2004 January 2004 31 AT LEAST FIVE TIMES A YEAR, FOR BICYCLERS John B. (but it might as well be anybody) messing around camp during a recent bicycle tour of Trinidad & Tobago. When Most Dads Had an Elephant Gun and Most Kids Were Part Cherokee e took an email poll and asked you to choose ing who I am, but when I ride my bike, I want to be able to look between four issues per year at 48 to 56 pages, and disheveled and ride however I’m riding without representing six issue per year at 32 to 40 pages. It was about Rivendell. I generally make minimal changes to my hair or W 35-to-1 in favor of more & shorter, with about 220 clothing before going on a ride, and I don’t shoot for a particu- precincts reporting. This issue is 48 pages, because lar look, so I eat breakfast and go out with bad hair, and I don’t it was going to be 56, but then I pulled eight to give me a good out myself. start on the next one, the first of the shorties. But in these conversations, often the fellow will say something about me or Rivendell that he wouldn’t say if he knew who I Last week as I was riding up the mountain, I came upon was, and then it’s too awkward to say it.