Unit 6 the Kadambas, the Chalukyas Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rural Tourism As an Entrepreneurial Opportunity (A Study on Hyderabad Karnataka Region)

Volume : 5 | Issue : 12 | December-2016 ISSN - 2250-1991 | IF : 5.215 | IC Value : 79.96 Original Research Paper Management Rural Tourism as an Entrepreneurial Opportunity (a Study on Hyderabad Karnataka Region) Assistant Professor, Dept of Folk Tourism,Karnataka Folklore Mr. Hanamantaraya University, Gotagodi -581197,Shiggaon TQ Haveri Dist, Karnataka Gouda State, India Assistant Professor, Dept of Folk Tourism,Karnataka Folklore Mr. Venkatesh. R University, Gotagodi -581197,Shiggaon TQ Haveri Dist, Karnataka State, India The Tourism Industry is seen as capable of being an agent of change in the landscape of economic, social and environment of a rural area. Rural Tourism activity has also generated employment and entrepreneurship opportunities to the local community as well as using available resources as tourist attractions. There are numerable sources to lead business in the tourism sector as an entrepreneur; the tourism sector has the potential to be a development of entrepreneurial and small business performance. Which one is undertaking setting up of business by utilizing all kinds sources definitely we can develop the region of that area. This article aims to discuss the extent of entrepreneurial opportunities as the development ABSTRACT of tourism in rural areas. Through active participation among community members, rural entrepreneurship will hopefully move towards prosperity and success of rural tourism entrepreneurship Rural Tourism, Entrepreneurial opportunities of Rural Tourism, and Development of Entrepre- KEYWORDS neurship in Rural area Introduction Objectives of the studies Top tourism destinations, particularly in developing countries, 1. To know the entrepreneurial opportunities in Rural are include national parks, wilderness areas, mountains, lakes, and of HK region cultural sites, most of which are generally rural. -

Shiva's Waterfront Temples

Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2015 © 2015 Subhashini Kaligotla All rights reserved ABSTRACT Shiva’s Waterfront Temples: Reimagining the Sacred Architecture of India’s Deccan Region Subhashini Kaligotla This dissertation examines Deccan India’s earliest surviving stone constructions, which were founded during the 6th through the 8th centuries and are known for their unparalleled formal eclecticism. Whereas past scholarship explains their heterogeneous formal character as an organic outcome of the Deccan’s “borderland” location between north India and south India, my study challenges the very conceptualization of the Deccan temple within a binary taxonomy that recognizes only northern and southern temple types. Rejecting the passivity implied by the borderland metaphor, I emphasize the role of human agents—particularly architects and makers—in establishing a dialectic between the north Indian and the south Indian architectural systems in the Deccan’s built worlds and built spaces. Secondly, by adopting the Deccan temple cluster as an analytical category in its own right, the present work contributes to the still developing field of landscape studies of the premodern Deccan. I read traditional art-historical evidence—the built environment, sculpture, and stone and copperplate inscriptions—alongside discursive treatments of landscape cultures and phenomenological and experiential perspectives. As a result, I am able to present hitherto unexamined aspects of the cluster’s spatial arrangement: the interrelationships between structures and the ways those relationships influence ritual and processional movements, as well as the symbolic, locative, and organizing role played by water bodies. -

BHIC-105 English.Pmd

BHIC-105 HISTORY OF INDIA-III (750 - 1206 CE) School of Social Sciences Indira Gandhi National Open University EXPERT COMMITTEE Prof. Kapil Kumar (Convenor) Prof. Makhan Lal Chairperson Director Faculty of History Delhi Institute of Heritage, School of Social Sciences Research and Management IGNOU, New Delhi New Delhi Prof. P. K. Basant Dr. Sangeeta Pandey Faculty of Humanities and Languages Faculty of History Jamia Milia Islamia School of Social Sciences New Delhi IGNOU, New Delhi Prof. D. Gopal Director, SOSS, IGNOU, New Delhi Course Coordinator : Prof. Nandini Sinha Kapur COURSE TEAM Prof. Nandini Sinha Kapur Dr. Suchi Dayal Dr. Abhishek Anand COURSE PREPARATION TEAM Unit no. Course Writer Dr. Khushboo Kumari Academic Counsellor Dr. Suchi Dayal 1 Non Collegiate Women’s Education Board Academic Consultant, Faculty of History School (Bharati College), University of Delhi of Social Sciences, IGNOU, New Delhi Dr. Avantika Sharma Dr. Ashok Shettar 8 2* Department of History, I.P. College for Karnataka University, Dharwad Women, Delhi University, Delhi Dr. Pintu Kumar 3** Dr. Richa Singh Assistant Professor 9 Ph.D from Centre for Historical Studies Motilal Nehru College (Evening) Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Delhi University Professor Champaklakshmi Dr. Naina Dasgupta 10****** Retired from Center for Historical Studies National Open School, Kailash Colony Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi New Delhi and Dr. Sangeeta Pandey Dr. V. K. Jain Faculty of History Department of History School of Social Sciences IGNOU, New Delhi University of Delhi, Delhi 4*** Prof. Y. Subbarayalu, Head Prof. Harbans Mukhia Indology Department, Retired from Centre for Historical Studies French Institute of Pondicherry, Puducherry Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Dr. -

A Study of Buddhist Sites in Karnataka

International Journal of Academic Research and Development International Journal of Academic Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4197 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.academicjournal.in Volume 3; Issue 6; November 2018; Page No. 215-218 A study of Buddhist sites in Karnataka Dr. B Suresha Associate Professor, Department of History, Govt. Arts College (Autonomous), Chitradurga, Karnataka, India Abstract Buddhism is one of the great religion of ancient India. In the history of Indian religions, it occupies a unique place. It was founded in Northern India and based on the teachings of Siddhartha, who is known as Buddha after he got enlightenment in 518 B.C. For the next 45 years, Buddha wandered the country side teaching what he had learned. He organized a community of monks known as the ‘Sangha’ to continue his teachings ofter his death. They preached the world, known as the Dharma. Keywords: Buddhism, meditation, Aihole, Badami, Banavasi, Brahmagiri, Chandravalli, dermal, Haigunda, Hampi, kanaginahally, Rajaghatta, Sannati, Karnataka Introduction of Ashoka, mauryanemperor (273 to 232 B.C.) it gained royal Buddhism is one of the great religion of ancient India. In the support and began to spread more widely reaching Karnataka history of Indian religions, it occupies a unique place. It was and most of the Indian subcontinent also. Ashokan edicts founded in Northern India and based on the teachings of which are discovered in Karnataka delineating the basic tents Siddhartha, who is known as Buddha after he got of Buddhism constitute the first written evidence about the enlightenment in 518 B.C. For the next 45 years, Buddha presence of the Buddhism in Karnataka. -

1 Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: 1 Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title South Indian kingdoms : pallavas and chalukyas Module Id I C/ OIH/ 15 Political developments in South India after Pre-requisites Satavavahana and Sangam age To study the Political and Cultural history of South Objectives India under Pallava and Chalukyan periods Keywords Pallava / Kanchi / Chalukya / Badami E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Introduction The period from C.300 CE to 750 CE marks the second historical phase in the regions south of the Vindhyas. In the first phase we notice the ascendency of the Satavahanas over the Deccan and that of the Sangam Age Kingdoms in Southern Tamilnadu. In these areas and also in Vidarbha from 3rd Century to 6th Century CE there arose about two dozen states which are known to us from their land charters. In Northern Maharashtra and Vidarbha (Berar) the Satavahanas were succeeded by the Vakatakas. Their political history is of more importance to the North India than the South India. But culturally the Vakataka kingdom became a channel for transmitting Brahmanical ideas and social institutions to the South. The Vakataka power was followed by that of the Chalukyas of Badami who played an important role in the history of the Deccan and South India for about two centuries until 753 CE when they were overthrown by their feudatories, the Rashtrakutas. The eastern part of the Satavahana Kingdom, the Deltas of the Krishna and the Godavari had been conquered by the Ikshvaku dynasty in the 3rd Century CE. -

Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title Mahajanapadas- Rise of Magadha – Nandas – Invasion of Alexander Module Id I C/ OIH/ 08 Pre requisites Early History of India Objectives To study the Political institutions of Ancient India from earliest to 3rd Century BCE. Mahajanapadas , Rise of Magadha under the Haryanka, Sisunaga Dynasties, Nanda Dynasty, Persian Invasions, Alexander’s Invasion of India and its Effects Keywords Janapadas, Magadha, Haryanka, Sisunaga, Nanda, Alexander E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Sources Political and cultural history of the period from C 600 to 300 BCE is known for the first time by a possibility of comparing evidence from different kinds of literary sources. Buddhist and Jaina texts form an authentic source of the political history of ancient India. The first four books of Sutta pitaka -- the Digha, Majjhima, Samyutta and Anguttara nikayas -- and the entire Vinaya pitaka were composed between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. The Sutta nipata also belongs to this period. The Jaina texts Bhagavati sutra and Parisisthaparvan represent the tradition that can be used as historical source material for this period. The Puranas also provide useful information on dynastic history. A comparison of Buddhist, Puranic and Jaina texts on the details of dynastic history reveals more disagreement. This may be due to the fact that they were compiled at different times. Apart from indigenous literary sources, there are number of Greek and Latin narratives of Alexander’s military achievements. They describe the political situation prevailing in northwest on the eve of Alexander’s invasion. -

A Case Study of Cultural History of Harapanahalli in the Kannada Inscriptions of the Taluk”

www.ijcrt.org © 2018 IJCRT | Volume 6, Issue 2 April 2018 | ISSN: 2320-2882 “A case study of cultural history of Harapanahalli in the Kannada inscriptions of the taluk” Prof. M.Vijaykumar Asst Professor Government First Grade College – Harapanahalli Abstarct: Harapanahalli region played an important role keeping intact Kananda language and culture. It was center of various empires imporatnat ones being Western Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas,Vijayanagara. The present paper seeks to unravel these aspects through study of cultural history of Harapanahalli in the Kannada inscriptions of the taluk.The Western Chalukyas played an important role in art and cultrure development in the region.The Western Chalukyas developed an architectural style known today as a transitional style, an architectural link between the style of the early Chalukya dynasty and that of the later Hoysala empire. Most of its monuments are in the districts bordering the Tungabhadra River in central Karnataka. Well known examples are the theMallikarjuna Temple at Kuruvatti, the Kallesvara Temple at Bagali and the Mahadeva Temple at Itagi. This was an important period in the development of fine arts in Southern India, especially in literature as the Western Chalukya kings encouraged writers in the native language Kannada, and Sanskrit.Knowledge of Western Chalukya history has come through examination of the numerous Kannada language inscriptions left by the kings (scholars Sheldon Pollock and Jan Houben have claimed 90 percent of the Chalukyan royal inscriptions are in Kannada), and from the study of important contemporary literary documents in Western Chalukya literature such as GadaYuddha (982) in Kannada by Ranna and VikramankadevaCharitam (1120) in Sanskrit by Bilhana. -

Outline Itinerary

About the tour: This historic tour begins in I Tech city Bangalore and proceed to the former princely state Mysore rich in Imperial heritage. Visit intrinsically Hindu collection of temples at Belure, Halebidu, Hampi, Badami, Aihole & Pattadakal, to see some of India's most intricate historical stone carvings. At the end unwind yourself in Goa, renowned for its endless beaches, places of worship & world heritage architecture. Outline Itinerary Day 01; Arrive Bangalore Day 02: Bangalore - Mysore (145kms/ 3hrs approx) Day 03: Mysore - Srirangapatna - Shravanabelagola - Hassan (140kms/ 3hrs approx) Day 04; Hassan – Belur – Halebidu – Hospet/ Hampi (310kms – 6-7hrs approx) Day 05; Hospet & Hampi Day 06; Hospet - Lakkundi – Gadag – Badami (130kms/ 3hrs approx) Day 07; Badami – Aihole – Pattadakal – Badami (80kms/ round) Day 08; Badami – Goa (250kms/ 5hrs approx) Day 09; Goa Day 10; Goa Day 11; Goa – Departure House No. 1/18, Top Floor, DDA Flats, Madangir, New Delhi 110062 Mob +91-9810491508 | Email- [email protected] | Web- www.agoravoyages.com Price details: Price using 3 star hotels valid from 1st October 2018 till 31st March 2019 (5% Summer discount available from 1st April till travel being completed before 30th September 2018 on 3star hotels price) Per person price sharing DOUBLE/ Per person price sharing TRIPLE (room Per person price staying in SINGLE Particular TWIN rooms with extra bed) rooms rooms Currency INR Euro USD INR Euro USD INR Euro USD 1 person N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A N/A ₹180,797 € 2,260 $2,825 2 person ₹96,680 € 1,208 -

Economic and Cultural History of Tamilnadu from Sangam Age to 1800 C.E

I - M.A. HISTORY Code No. 18KP1HO3 SOCIO – ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF TAMILNADU FROM SANGAM AGE TO 1800 C.E. UNIT – I Sources The Literay Sources Sangam Period The consisted, of Tolkappiyam a Tamil grammar work, eight Anthologies (Ettutogai), the ten poems (Padinen kell kanakku ) the twin epics, Silappadikaram and Manimekalai and other poems. The sangam works dealt with the aharm and puram life of the people. To collect various information regarding politics, society, religion and economy of the sangam period, these works are useful. The sangam works were secular in character. Kallabhra period The religious works such as Tamil Navalar Charital,Periyapuranam and Yapperumkalam were religious oriented, they served little purpose. Pallava Period Devaram, written by Apper, simdarar and Sambandar gave references tot eh socio economic and the religious activities of the Pallava age. The religious oriented Nalayira Tivya Prabandam also provided materials to know the relation of the Pallavas with the contemporary rulers of South India. The Nandikkalambakam of Nandivarman III and Bharatavenba of Perumdevanar give a clear account of the political activities of Nandivarman III. The early pandya period Limited Tamil sources are available for the study of the early Pandyas. The Pandikkovai, the Periyapuranam, the Divya Suri Carita and the Guruparamparai throw light on the study of the Pandyas. The Chola Period The chola empire under Vijayalaya and his successors witnessed one of the progressive periods of literary and religious revival in south India The works of South Indian Vishnavism arranged by Nambi Andar Nambi provide amble information about the domination of Hindu religion in south India. -

ANCIENT INDIA All Bights Reserved ANCIENT INDIA

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Date ANCIENT INDIA All Bights reserved ANCIENT INDIA BY S. KRISHNASWAMI AIYANGAE, M.A. Member of the Royal Asiatic Society of Oreal Britain and Ireland Fellow of the Roijal Bistorical Society, London. Member ol the Board of Studies, and Examiner in History and Economics. Vnirersity of Madras Mysore Education Serria: WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY VINCENT A. SMITH, M.A., I.C.S. (retired) ' Author of the ' Early History of India LONDON: LUZAC & Co., IC great kussell isteeet MADEAS: S.P.C.K. DEPOSITORY, VEPBEY 1911 1)5 4-04- /\fl 6 ^,©XKg^ PRINTED AT THE :. PKESS, VEPBKY, MADRAS 1911 "^QXYS^ ) INSCRIBED TO THE :ME:M0RY OP JOHN WEIE [Inspector-General op Education in JIybore] ( November 1, 1909—July 31, 1911 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022968840 PEEFACE The first chapter deals with the early portion of Indian History, and so the title ' Ancient India ' has been given to the book. The other chapters deal with a variety ot subjects, and are based on lectures given on different occa- sions. One was originally prepared as my thesis for the M.A. Degree Examination of the University of Madras. The favourable reception given to my early work by historical and oriental scholars encouraged me to put my researches into a more permanent form, which a liberal grant from the Madras School Book and Literature Society has enabled me to do. -

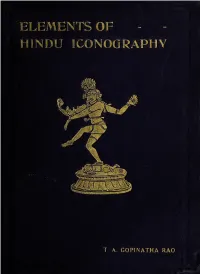

Elements of Hindu Iconography

6 » 1 m ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY. ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY BY T. A. GOPINATHA RAO. M.A., SUPERINTENDENT OF ARCHiEOLOGY, TRAVANCORE STATE. Vol. II—Part II. THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD :: :: MADRAS 1916 Ail Rights Reserved. i'. f r / rC'-Co, HiSTor ir.iL medical PRINTED AT THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD, MADRAS. MISCELLANEOUS ASPECTS OF SIVA Sadasivamurti and Mahasada- sivamurti, Panchabrahmas or Isanadayah, Mahesamurti, Eka- dasa Rudras, Vidyesvaras, Mur- tyashtaka and Local Legends and Images based upon Mahat- myas. : MISCELLANEOUS ASPECTS OF SIVA. (i) sadasTvamueti and mahasadasivamueti. he idea implied in the positing of the two T gods, the Sadasivamurti and the Maha- sadasivamurti contains within it the whole philo- sophy of the Suddha-Saiva school of Saivaism, with- out an adequate understanding of which it is not possible to appreciate why Sadasiva is held in the highest estimation by the Saivas. It is therefore unavoidable to give a very short summary of the philosophical aspect of these two deities as gathered from the Vatulasuddhagama. According to the Saiva-siddhantins there are three tatvas (realities) called Siva, Sadasiva and Mahesa and these are said to be respectively the nishJcald, the saJcald-nishJcald and the saJcaW^^ aspects of god the word kald is often used in philosophy to imply the idea of limbs, members or form ; we have to understand, for instance, the term nishkald to mean (1) Also iukshma, sthula-sukshma and sthula, and tatva, prabhdva and murti. 361 46 HINDU ICONOGEAPHY. has foroa that which do or Imbs ; in other words, an undifferentiated formless entity. -

ELEMENTS of HINDU ICONOGRAPHY CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY All Books Are Subject to Recall After Two Weeks Olin/Kroch Library DATE DUE Cornell University Library

' ^'•' .'': mMMMMMM^M^-.:^':^' ;'''}',l.;0^l!v."';'.V:'i.\~':;' ' ASIA LIBRARY ANNEX 2 ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY All books are subject to recall after two weeks Olin/Kroch Library DATE DUE Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071128841 ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY. CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 071 28 841 ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY BY T. A.^GOPINATHA RAO. M.A. SUPERINTENDENT OF ARCHEOLOGY, TRAVANCORE STATE. Vol. II—Part I. THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD :: :: MADRAS 1916 All Rights Reserved. KC- /\t^iS33 PRINTED AT THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE, MOUNT ROAD, MADRAS. DEDICATED WITH KIND PERMISSION To HIS HIGHNESS SIR RAMAVARMA. Sri Padmanabhadasa, Vanchipala, Kulasekhara Kiritapati, Manney Sultan Maharaja Raja Ramaraja Bahadur, Shatnsher Jang, G.C.S.I., G.C.I. E., MAHARAJA OF TRAVANCORE, Member of the Royal Asiatic Society, London, Fellow of the Geographical Society, London, Fellow of the Madras University, Officer de L' Instruction Publique. By HIS HIGHNESSS HUMBLE SERVANT THE AUTHOR. PEEFACE. In bringing out the Second Volume of the Elements of Hindu Iconography, the author earnestly trusts that it will meet with the same favourable reception that was uniformly accorded to the first volume both by savants and the Press, for which he begs to take this opportunity of ten- dering his heart-felt thanks. No pains have of course been spared to make the present publication as informing and interesting as is possible in the case of the abstruse subject of Iconography.