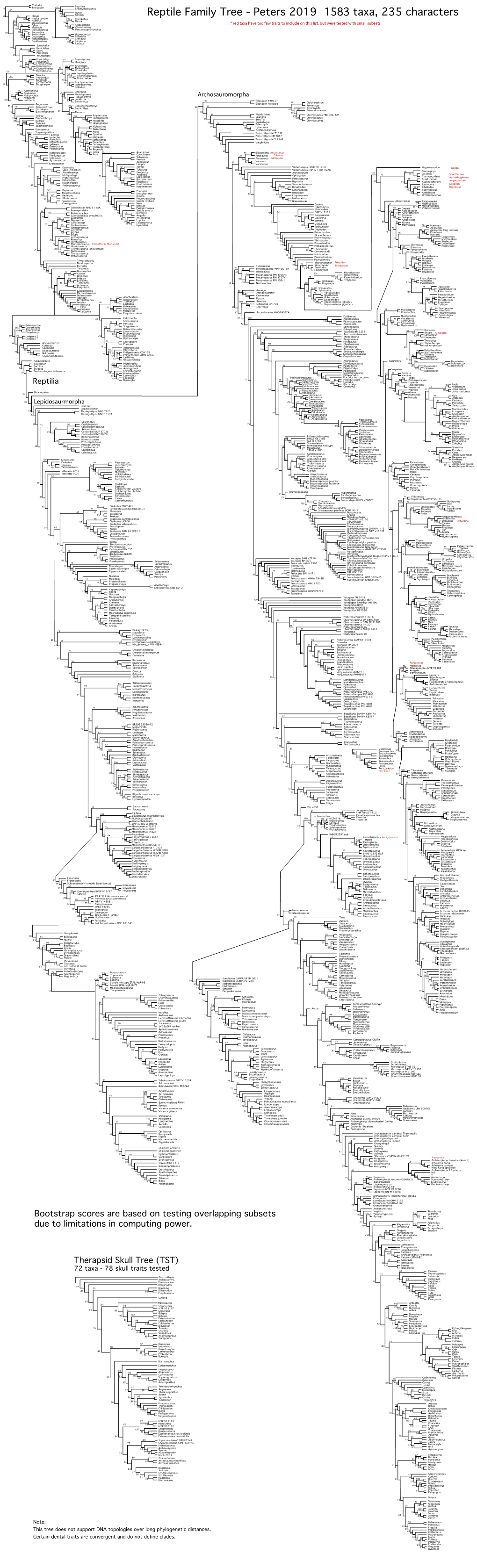

Reptile Family Tree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carpenter 1999 EL PLESIOSAURIO DE VILLA DE LEYVA (BOYACÁ, COLOMBIA)

Boletín de Geología Vol. 23, No. 38, Enero-Junio de 2001 Callawayasaurus colombiensis (Welles) Carpenter 1999 EL PLESIOSAURIO DE VILLA DE LEYVA (BOYACÁ, COLOMBIA). ¿UN NUEVO ESPÉCIMEN? Jerez Jaimes, J. H1.; Narváez Parra, E. X1. RESUMEN En los depósitos del Cretácico (Aptiano) de Villa de Leyva se han reportado dos especies de plesiosaurios, un pliosaurio Kronosaurus boyacensis Hampe 1992, y un plesiosaurio Callawayasaurus colombiensis (Welles) Carpenter, 1999 (= Alzadasaurus colombiensis Welles, 1962). Se realiza la determinación de un espécimen de elasmosaurio encontrado por los pobladores de la zona rural de Villa de Leyva en 1999 con base en material fotográfico del mismo, siendo muy probable que corresponda a la especie Callawayasaurus colombiensis (Welles) Carpenter, 1999. Palabras Claves: Cretácico, Plesiosaurios, Villa de Leyva. ABSTRACT In the deposits of the Cretaceous (Aptian) of Villa de Leyva two plesiosaurs species have been reported, a pliosaur Kronosaurus boyacensis Hampe 1992, and a plesiosaur Callawayasaurus colombiensis (Welles) Carpenter, 1999 (= Alzadasaurus colombiensis Welles, 1962). We carried out the determination of elasmosaur specimen found by the inhabitants of the rural area of Villa de Leyva in 1999, on the basis of photographic material of it. Probably it corresponds to the Callawayasaurus colombiensis specie (Welles) Carpenter, 1999. Key Words: Cretaceous, Plesiosaurs, Villa de Leyva. 1Biólogos, Calle 10A # 24-68 Bucaramanga, Santander (Colombia). Correo electrónico: [email protected] Callawayasaurus -

Estimating the Evolutionary Rates in Mosasauroids and Plesiosaurs: Discussion of Niche Occupation in Late Cretaceous Seas

Estimating the evolutionary rates in mosasauroids and plesiosaurs: discussion of niche occupation in Late Cretaceous seas Daniel Madzia1 and Andrea Cau2 1 Department of Evolutionary Paleobiology, Institute of Paleobiology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland 2 Independent, Parma, Italy ABSTRACT Observations of temporal overlap of niche occupation among Late Cretaceous marine amniotes suggest that the rise and diversification of mosasauroid squamates might have been influenced by competition with or disappearance of some plesiosaur taxa. We discuss that hypothesis through comparisons of the rates of morphological evolution of mosasauroids throughout their evolutionary history with those inferred for contemporary plesiosaur clades. We used expanded versions of two species- level phylogenetic datasets of both these groups, updated them with stratigraphic information, and analyzed using the Bayesian inference to estimate the rates of divergence for each clade. The oscillations in evolutionary rates of the mosasauroid and plesiosaur lineages that overlapped in time and space were then used as a baseline for discussion and comparisons of traits that can affect the shape of the niche structures of aquatic amniotes, such as tooth morphologies, body size, swimming abilities, metabolism, and reproduction. Only two groups of plesiosaurs are considered to be possible niche competitors of mosasauroids: the brachauchenine pliosaurids and the polycotylid leptocleidians. However, direct evidence for interactions between mosasauroids and plesiosaurs is scarce and limited only to large mosasauroids as the Submitted 31 July 2019 predators/scavengers and polycotylids as their prey. The first mosasauroids differed Accepted 18 March 2020 from contemporary plesiosaurs in certain aspects of all discussed traits and no evidence Published 13 April 2020 suggests that early representatives of Mosasauroidea diversified after competitions with Corresponding author plesiosaurs. -

A Revision of the Classification of the Plesiosauria with a Synopsis of the Stratigraphical and Geographical Distribution Of

LUNDS UNIVERSITETS ARSSKRIFT. N. F. Avd. 2. Bd 59. Nr l. KUNGL. FYSIOGRAFISKA SÅLLSKAPETS HANDLINGAR, N. F. Bd 74. Nr 1. A REVISION OF THE CLASSIFICATION OF THE PLESIOSAURIA WITH A SYNOPSIS OF THE STRATIGRAPHICAL AND GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF THE GROUP BY PER OVE PERSSON LUND C. W. K. GLEER UP Read before the Royal Physiographic Society, February 13, 1963. LUND HÅKAN OHLSSONS BOKTRYCKERI l 9 6 3 l. Introduction The sub-order Plesiosauria is one of the best known of the Mesozoic Reptile groups, but, as emphasized by KuHN (1961, p. 75) and other authors, its classification is still not satisfactory, and needs a thorough revision. The present paper is an attempt at such a revision, and includes also a tabular synopsis of the stratigraphical and geo graphical distribution of the group. Some of the species are discussed in the text (pp. 17-22). The synopsis is completed with seven maps (figs. 2-8, pp. 10-16), a selective synonym list (pp. 41-42), and a list of rejected species (pp. 42-43). Some forms which have been erroneously referred to the Plesiosauria are also briefly mentioned ("Non-Plesiosaurians", p. 43). - The numerals in braekets after the generic and specific names in the text refer to the tabular synopsis, in which the different forms are numbered in successional order. The author has exaroined all material available from Sweden, Australia and Spitzbergen (PERSSON 1954, 1959, 1960, 1962, 1962a); the major part of the material from the British Isles, France, Belgium and Luxembourg; some of the German spec imens; certain specimens from New Zealand, now in the British Museum (see LYDEK KER 1889, pp. -

How Plesiosaurs Swam: New Insights Into Their Underwater Flight Using “Ava”, a Virtual Pliosaur

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 9 October 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201910.0094.v1 How Plesiosaurs Swam: New Insights into Their Underwater Flight Using “Ava”, a Virtual Pliosaur Max Hawthorne1,*, Mark A. S. McMenamin 2, Paul de la Salle3 1Far From The Tree Press, LLC, 4657 York Rd., #952, Buckingham, PA, 18912, United States 2Department of Geology and Geography, Mount Holyoke College, South Hadley, Massachusetts, United States 3Swindon, England *Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: 267-337-7545 Abstract Analysis of plesiosaur swim dynamics by means Further study attempted to justify the use of all four flippers of a digital 3D armature (wireframe “skeleton”) of a simultaneously via the use of paddle-generated vortices, pliosauromorph (“Ava”) demonstrates that: 1, plesiosaurs which require specific timing to achieve optimal additional used all four flippers for primary propulsion; 2, plesiosaurs thrust. These attempts have largely relied on anatomical utilized all four flippers simultaneously; 3, respective pairs studies of strata-compressed plesiosaur skeletons, and/or of flippers of Plesiosauridae, front and rear, traveled through preconceived notions as pertains to the paddles’ inherent distinctive, separate planes of motion, and; 4, the ability to ranges of motion [8, 10-12]. What has not been considered utilize all four paddles simultaneously allowed these largely are the opposing angles of the pectoral and pelvic girdles, predatory marine reptiles to achieve a significant increase in which strongly indicate varied-yet-complementing relations acceleration and speed, which, in turn, contributed to their between the front and rear sets of paddles, both in repose and sustained dominance during the Mesozoic. -

The Nonavian Theropod Quadrate II: Systematic Usefulness, Major Trends and Cladistic and Phylogenetic Morphometrics Analyses

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272162807 The nonavian theropod quadrate II: systematic usefulness, major trends and cladistic and phylogenetic morphometrics analyses Article · January 2014 DOI: 10.7287/peerj.preprints.380v2 CITATION READS 1 90 3 authors: Christophe Hendrickx Ricardo Araujo University of the Witwatersrand Technical University of Lisbon 37 PUBLICATIONS 210 CITATIONS 89 PUBLICATIONS 324 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Octávio Mateus University NOVA of Lisbon 224 PUBLICATIONS 2,205 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Nature and Time on Earth - Project for a course and a book for virtual visits to past environments in learning programmes for university students (coordinators Edoardo Martinetto, Emanuel Tschopp, Robert A. Gastaldo) View project Ten Sleep Wyoming Jurassic dinosaurs View project All content following this page was uploaded by Octávio Mateus on 12 February 2015. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. The nonavian theropod quadrate II: systematic usefulness, major trends and cladistic and phylogenetic morphometrics analyses Christophe Hendrickx1,2 1Universidade Nova de Lisboa, CICEGe, Departamento de Ciências da Terra, Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia, Quinta da Torre, 2829-516, Caparica, Portugal. 2 Museu da Lourinhã, 9 Rua João Luis de Moura, 2530-158, Lourinhã, Portugal. s t [email protected] n i r P e 2,3,4,5 r Ricardo Araújo P 2 Museu da Lourinhã, 9 Rua João Luis de Moura, 2530-158, Lourinhã, Portugal. 3 Huffington Department of Earth Sciences, Southern Methodist University, PO Box 750395, 75275-0395, Dallas, Texas, USA. -

Mosasaurs Continuing from Last Time…

Pliosaurs and Mosasaurs Continuing From Last Time… • Pliosauridae: the big marine predators of the Jurassic Pliosauridae • Some of the largest marine predators of all time, these middle Jurassic sauropterygians include such giants as Kronosaurus, Liopleurodon, Macroplata, Peloneustes, Pliosaurus, and Brachauchenius Pliosaur Mophology • While the number of cervical vertebrae is less than in plesiosaurs, there is still variation: Macroplata (29) vs. Kronosaurus (13) Pliosaur Morphology • Larger pliosaurs adopted a more streamlined body shape, like modern whales, with a large skull and compact neck, and generally the hind limbs were larger than the front, while plesiosaurs had larger forelimbs Pliosaur Morphology • Powerful limb girdles and large (banana sized) conical teeth helped pliosaurs eat larger, quicker prey than the piscivorous plesiosaurs Liopleurodon • NOT 25 m long in general (average of 40 feet), though perhaps certain individuals could reach that size, making Liopleurodon ferox the largest carnivore to ever live • Recent skull studies indicate that Liopleurodon could sample water in stereo through nostrils, locating scents much as we locate sound Cretaceous Seas • Breakup of Gondwana causes large undersea mountain chains to form, raising sea levels everywhere • Shallow seas encourage growth of corals, which increases calcium abundance and chalk formation • Warm seas and a gentle thermal gradient yield a hospitable environment to rays, sharks, teleosts, and the first radiation of siliceous diatoms Kronosaurus • Early Cretaceous -

Late Cretaceous) of Morocco : Palaeobiological and Behavioral Implications Remi Allemand

Endocranial microtomographic study of marine reptiles (Plesiosauria and Mosasauroidea) from the Turonian (Late Cretaceous) of Morocco : palaeobiological and behavioral implications Remi Allemand To cite this version: Remi Allemand. Endocranial microtomographic study of marine reptiles (Plesiosauria and Mosasauroidea) from the Turonian (Late Cretaceous) of Morocco : palaeobiological and behavioral implications. Paleontology. Museum national d’histoire naturelle - MNHN PARIS, 2017. English. NNT : 2017MNHN0015. tel-02375321 HAL Id: tel-02375321 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-02375321 Submitted on 22 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. MUSEUM NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE Ecole Doctorale Sciences de la Nature et de l’Homme – ED 227 Année 2017 N° attribué par la bibliothèque |_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_|_| THESE Pour obtenir le grade de DOCTEUR DU MUSEUM NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE Spécialité : Paléontologie Présentée et soutenue publiquement par Rémi ALLEMAND Le 21 novembre 2017 Etude microtomographique de l’endocrâne de reptiles marins (Plesiosauria et Mosasauroidea) du Turonien (Crétacé supérieur) du Maroc : implications paléobiologiques et comportementales Sous la direction de : Mme BARDET Nathalie, Directrice de Recherche CNRS et les co-directions de : Mme VINCENT Peggy, Chargée de Recherche CNRS et Mme HOUSSAYE Alexandra, Chargée de Recherche CNRS Composition du jury : M. -

Reptiles Fósiles De Colombia Un Aporte Al Conocimiento Y a La Enseñanza Del Patrimonio Paleontológico Del País

Reptiles Fósiles de Colombia Un aporte al conocimiento y a la enseñanza del patrimonio paleontológico del país Luis Gonzalo Ortiz-Pabón Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Facultad de Ciencia y tecnología Departamento de biología Bogotá D.C. 2020 Reptiles Fósiles de Colombia Un aporte al conocimiento y a la enseñanza del patrimonio paleontológico del país Luis Gonzalo Ortiz-Pabón Trabajo presentado como requisito para optar por el título de: Licenciado en Biología Directora: Heidy Paola Jiménez Medina MSc. Línea de Investigación: Educación en Ciencias y formación Ambiental Grupo de Investigación: Educación en Ciencias, Ambiente y Diversidad Universidad Pedagógica Nacional Facultad de Ciencia y tecnología Departamento de biología Bogotá D.C. 2020 Dedicatoria A mi mami, quien ha estado acompañándome y apoyándome en muchos de los momentos definitivos de mi vida, además de la deuda que tengo con ella desde 2008. “La ciencia no es una persecución despiadada de información objetiva. Es una actividad humana creativa, sus genios actúan más como artistas que como procesadores de información” Stephen J. Gould Agradecimientos En primera instancia agradezco a todos los maestros y maestras que fueron parte esencial de mi formación académica. Agradecimiento especial al Ilustrador y colega Marco Salazar por su aporte gráfico a la construcción del libro Reptiles Fósiles de Colombia, a Oscar Hernández y a Galdra Films por su valioso aporte en la diagramación y edición del libro, a Heidy Jiménez quien fue mi directora y guía en el desarrollo de este trabajo y a Vanessa Robles, quien estuvo acompañando la revisión del libro y este escrito, además del apoyo emocional brindado en todo momento. -

The Dinosaur Field Guide Supplement

The Dinosaur Field Guide Supplement September 2010 – December 2014 By, Zachary Perry (ZoPteryx) Page 1 Disclaimer: This supplement is intended to be a companion for Gregory S. Paul’s impressive work The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, and as such, exhibits some similarities in format, text, and taxonomy. This was done solely for reasons of aesthetics and consistency between his book and this supplement. The text and art are not necessarily reflections of the ideals and/or theories of Gregory S. Paul. The author of this supplement was limited to using information that was freely available from public sources, and so more information may be known about a given species then is written or illustrated here. Should this information become freely available, it will be included in future supplements. For genera that have been split from preexisting genera, or when new information about a genus has been discovered, only minimal text is included along with the page number of the corresponding entry in The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Genera described solely from inadequate remains (teeth, claws, bone fragments, etc.) are not included, unless the remains are highly distinct and cannot clearly be placed into any other known genera; this includes some genera that were not included in Gregory S. Paul’s work, despite being discovered prior to its publication. All artists are given full credit for their work in the form of their last name, or lacking this, their username, below their work. Modifications have been made to some skeletal restorations for aesthetic reasons, but none affecting the skeleton itself. -

A Cladistic Analysis and Taxonomic Revision of the Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) F

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Biological Sciences Faculty Research Biological Sciences 12-2001 A Cladistic Analysis and Taxonomic Revision of the Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) F. Robin O’Keefe Marshall University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/bio_sciences_faculty Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Other Animal Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Frank Robin O’Keefe (2001). A cladistic analysis and taxonomic revision of the Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia). ). Acta Zoologica Fennica 213: 1-63. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Faculty Research by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Acta Zool. Fennica 213: 1–63 ISBN 951-9481-58-3 ISSN 0001-7299 Helsinki 11 December 2001 © Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board 2001 A cladistic analysis and taxonomic revision of the Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) Frank Robin O’Keefe Department of Anatomy, New York College of Osteopathic Medicine, Old Westbury, New York 11568, U.S.A Received 13 February 2001, accepted 17 September 2001 O’Keefe F. R. 2001: A cladistic analysis and taxonomic revision of the Plesio- sauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia). — Acta Zool. Fennica 213: 1–63. The Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia) is a group of Mesozoic marine reptiles known from abundant material, with specimens described from all continents. The group originated very near the Triassic–Jurassic boundary and persisted to the end- Cretaceous mass extinction. This study describes the results of a specimen-based cladistic study of the Plesiosauria, based on examination of 34 taxa scored for 166 morphological characters. -

The Macroevolutionary Landscape of Short-Necked Plesiosaurians Collapsed to a Unimodal Distribution

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The macroevolutionary landscape of short‑necked plesiosaurians Valentin Fischer1*, Jamie A. MacLaren1, Laura C. Soul2, Rebecca F. Bennion1,3, Patrick S. Druckenmiller4 & Roger B. J. Benson5 Throughout their evolution, tetrapods have repeatedly colonised a series of ecological niches in marine ecosystems, producing textbook examples of convergent evolution. However, this evolutionary phenomenon has typically been assessed qualitatively and in broad‑brush frameworks that imply simplistic macroevolutionary landscapes. We establish a protocol to visualize the density of trait space occupancy and thoroughly test for the existence of macroevolutionary landscapes. We apply this protocol to a new phenotypic dataset describing the morphology of short‑necked plesiosaurians, a major component of the Mesozoic marine food webs (ca. 201 to 66 Mya). Plesiosaurians evolved this body plan multiple times during their 135-million-year history, making them an ideal test case for the existence of macroevolutionary landscapes. We fnd ample evidence for a bimodal craniodental macroevolutionary landscape separating latirostrines from longirostrine taxa, providing the frst phylogenetically-explicit quantitative assessment of trophic diversity in extinct marine reptiles. This bimodal pattern was established as early as the Middle Jurassic and was maintained in evolutionary patterns of short‑necked plesiosaurians until a Late Cretaceous (Turonian) collapse to a unimodal landscape comprising longirostrine forms with novel morphologies. This study highlights the potential of severe environmental perturbations to profoundly alter the macroevolutionary dynamics of animals occupying the top of food chains. Amniotes are ’land vertebrates’, but have nevertheless undergone at least 69 independent evolutionary transi- tions from land into aquatic environments 1. Sea-going (marine) amniotes are textbook examples of inter- and intraclade convergent evolution, with repeated acquisitions of short, hydrodynamic body plans 2–9. -

Journal of Zoological and Bioscience Research -Volume 4, Issue 2, Page No: 7-13 Copyright CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Available Online At

Journal of Zoological and Bioscience Research -Volume 4, Issue 2, Page No: 7-13 Copyright CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 Available Online at: www.journalzbr.com ISSN No: 2349-2856 Teihivenator gen. nov., A new generic name for the Tyrannosauroid Dinosaur "Laelaps" Macropus (Cope, 1868; preoccupied by Koch, 1836) Chan-gyu Yun 1,2 1Vertebrate Paleontological Institute of Incheon, Incheon 21974, Republic of Korea 2Biological Sciences, Inha University, Incheon 22212, Republic of Korea DOI: 10.24896/jzbr.2017422 ABSTRACT Once referred to the ornithomimosaur 'Coelosaurus' antiquus, 'Laelaps' macropusspecimens from the Navesink Formation (Late Campanian-Early Maastrichtian, Late Cretaceous) of New Jersey, USA was separated as a new species of 'Laelaps' by paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope in 1868. While it was revealed later that 'Laelaps' is preoccupied by laelapidae mite Laelaps agilis and renamed as Dryptosaurus, the taxonomic history of 'Laelaps' macropuswas controversial and sometimes considered as dubious. Here I show 'Laelaps' macropusas a valid taxon of tyrannosauroid based on comparisons with other taxa; there are considerable differences between 'Laelaps' macropusand Dryptosaurus aquilunguis. Therefore, a new generic name for 'Laelaps' macropus,Teihivenatorgen. nov. is erected here. Key words : Dinosauria; Theropoda; Tyrannosauroidea; Teihivenator ; Dryptosaurus HOW TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Chan-gyu Yun, Teihivenator gen. nov., a new generic name for the tyrannosauroid dinosaur "Laelaps" macropus (Cope, 1868; preoccupied by Koch, 1836). J Zool Biosci Res, 2017, 4 (2): 7-13 , DOI: 10.24896/jzbr.2017422 Corresponding author : Chan-gyu Yun and abundance of marine deposits [28]. So, it is an e-mail *[email protected] undoubted fact that any new discoveries from this Received: 02/02/2017 area would be important for understanding Accepted: 15/05/2017 dinosaur evolution or diversity from this forgotten continent.