Proposal for the Registry of the Latin American And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER Winter/ Spring 2020 LETTER from the DIRECTOR

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research NEWSLETTER winter/ spring 2020 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, launch May 1 with an event at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. YIVO is thriving. 2019 was another year of exciting growth. Work proceeded on schedule for the Edward Other highlights include a fabulous segment on Mashable’s Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections and we anticipate online “What’s in the Basement?” series; a New York completion of this landmark project in December 2021. Times feature article (June 25, 2019) on the acquisition Millions of pages of never-before-seen documents and of the archive of Nachman Blumenthal; a Buzzfeed rare or unique books have now been digitized and put Newsletter article (December 22, 2019) on Chanukah online for researchers, teachers, and students around the photos in the DP camps; and a New Yorker article world to read. The next important step in developing (December 30, 2019) on YIVO’s Autobiographies. YIVO’s online capabilities is the creation of the Bruce and Francesca Cernia Slovin Online Museum of East YIVO is an exciting place to work, to study, to European Jewish Life. The museum will launch early explore, and to reconnect with the great treasures 2021. The first gallery, devoted to the autobiography of the Jewish heritage of Eastern Europe and Russia. of Beba Epstein, is currently being tested. Through Please come for a visit, sign up for a tour, or catch us the art of storytelling the museum will provide the online on our YouTube channel (@YIVOInstitute). historical context for the archive’s vast array of original documents, books, and other artifacts, with some materials being translated to English for the first time. -

American Jewish Yearbook

JEWISH STATISTICS 277 JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rest largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the num- bers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1910, the English " Jewish Year Book " for 5670-71, " The Jewish Ency- clopedia," Jildische Statistik, and the Alliance Israelite Uni- verselle reports. THE UNITED STATES ESTIMATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the religious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or natural- ized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimates. The Jewish population was estimated— In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. A. Berk at 50,000 In 1880 by Wm. B. Hackenburg at 230,257 In 1888 by Isaac Markens at 400,000 In 1897 by David Sulzberger at 937,800 In 1905 by "The Jewish Encyclopedia" at 1,508,435 In 1907 by " The American Jewish Year Book " at 1,777,185 In 1910 by " The American Je\rish Year Book" at 2,044,762 DISTRIBUTION The following table by States presents two sets of estimates. -

Jewish Out-Marriage: Mexico and Venezuela

International Roundtable on Intermarriage – Brandeis University, December 18, 2003 Jewish Out-Marriage: Mexico and Venezuela Sergio DellaPergola The Avraham Harman Institute of Contemporary Jewry The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and The Jewish People Policy Planning Institute Background This chapter deals with recent Jewish family developments in some Spanish speaking countries in the central areas of the American continent. While not the largest in size, during the second half of the 20th century these communities have represented remarkably successful examples of richly structured, attractive and resilient Jewish communities. The Latin American model of Jewish community organization developed in the context of relatively poor and highly polarized societies where social-class stratification often overlapped with differentials between the descendants of native civilizations and the descendants of settlers from Western European countries—primarily Spain. Throughout most of the 20th century the general political context of these societies was characterized by considerable concentrations of central presidential power within a state structure often formally organized in a federal format. Mexico and Venezuela featured a comparatively more stable political environment than other countries in Latin America. Mexico and Venezuela, the main focus of this paper, provide examples of Jewish populations generated by initially small international migration during the first half of the 20th century, and subsequent growth through further immigration and natural increase. Around the year 2000, the Jewish population was estimated at about 40,000 in Mexico, mostly concentrated in Mexico City, and 15,000 to 18,000 in Venezuela, mostly in Caracas. For many decades, Jews from Central and Eastern Europe constituted the preponderant element from the point of view of population size and internal power within these communities. -

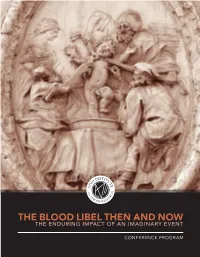

Read the Conference Program

COVER: Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent, Italy. Photo by Andreas Caranti. Via Wikimedia Commons. YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS CONFERENCE OCTOBER 9, 2016 CO-SPONSORED BY 1 INCE ITS FABRICATION IN THE MIDDLE AGES, the accusation that Jews Skidnapped, tortured and killed Christian children in mockery of Christ and the Crucifixion, or for the use of their blood, has been the basis for some of the most hateful examples of organized antisemitism. The blood libel has inspired expulsions and murder of Jews, tortures and forced mass conversions, and has served as an ines- capable focal point for wider strains of anti-Jewish sentiment that permeate learned and popular discourse, social and political thought, and cultural media. In light of contemporary manifestations of antisemitism around the world it is appropriate to re-examine the enduring history, the wide dissemination, and the persistent life of a historical and cultural myth—a bald lie—intended to demonize the Jewish people. This conference explores the impact of the blood libel over the centuries in a wide variety of geographic regions. It focuses on cultural memory: how cultural memory was created, elaborated, and transmitted even when based on no actual event. Scholars have treated the blood libel within their own areas of expertise—as medieval myth, early modern financial incentive, racial construct, modern catalyst for pogroms and the expulsion of Jews, and political scare tactic—but rarely have there been opportunities to discuss such subjects across chronological and disciplinary borders. We will look at the blood libel as historical phenomenon, legal justification, economic mechanism, and visual and literary trope with ongoing political repercussions. -

JUL 15 and the History of YIVO CECILE KUZNITZ | Delivered in English

MONDAY The Rise of Yiddish Scholarship JUL 15 and the History of YIVO CECILE KUZNITZ | Delivered in English As Jewish activists sought to build a modern, secular culture in the late nineteenth century they stressed the need to conduct research in and about Yiddish, the traditionally denigrated vernacular of European Jewry. By documenting and developing Yiddish and its culture, they hoped to win respect for the language and rights for its speakers as a national minority group. The Yidisher visnshaftlekher institut [Yiddish Scientific Institute], known by its acronym YIVO, was founded in 1925 as the first organization dedicated to Yiddish scholarship. Throughout its history, YIVO balanced its mission both to pursue academic research and to respond to the needs of the folk, the masses of ordinary Yiddish- speaking Jews. This talk will explore the origins of Yiddish scholarship and why YIVO’s work was seen as crucial to constructing a modern Jewish identity in the Diaspora. Cecile Kuznitz is Associate Professor of Jewish history and Director of Jewish Studies at Bard College. She received her Ph.D. in modern Jewish history from Stanford University and previously taught at Georgetown University. She has held fellowships at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies, and the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. In summer 2013 she was a Visiting Scholar at Vilnius University. She is the author of several articles on the history of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, the Jewish community of Vilna, and the field of Yiddish Studies. English-Language Bibliography of Recent Works on Yiddish Studies CECILE KUZNITZ Baker, Zachary M. -

Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico

Descendants of the Anusim (Crypto-Jews) in Contemporary Mexico Slightly updated version of a Thesis for the degree of “Doctor of Philosophy” by Schulamith Chava Halevy Hebrew University 2009 © Schulamith C. Halevy 2009-2011 This work was carried out under the supervision of Professor Yom Tov Assis and Professor Shalom Sabar To my beloved Berthas In Memoriam CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................7 1.1 THE PROBLEM.................................................................................................................7 1.2 NUEVO LEÓN ............................................................................................................ 11 1.2.1 The Original Settlement ...................................................................................12 1.2.2 A Sephardic Presence ........................................................................................14 1.2.3 Local Archives.......................................................................................................15 1.3 THE CARVAJAL TRAGEDY ....................................................................................... 15 1.4 THE MEXICAN INQUISITION ............................................................................. 17 1.4.1 José Toribio Medina and Alfonso Toro.......................................................17 1.4.2 Seymour Liebman ...............................................................................................18 1.5 CRYPTO‐JUDAISM -

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Re: Otto Frank File Embargoed Until

Prepared for: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research Re: Otto Frank File Embargoed until: February 14, 2007 at 10 AM EST BACKGROUND TO THE SITUATION OF JEWS IN THE NETHERLANDS UNDER NAZI OCCUPATION AND OF THE FAMILY OF OTTO FRANK By: David Engel Greenberg Professor of Holocaust Studies New York University Understanding the situation of Jews in the Netherlands under Nazi occupation, like understanding any aspect of the Holocaust, requires suspension of hindsight. No one could know in 1933, 1938, or even early 1941 that the Nazi regime would soon embark upon a systematic program aimed at killing each and every Jewish man, woman, and child within its reach. The statement is true of top German officials no less than it is of the Jewish and non-Jewish civilian populations of the twenty countries within the Nazi orbit and of the governments and peoples of the Allied and neutral countries. Although it is tempting to look back upon the history of Nazi anti-Jewish utterances and measures and to detect in them an ostensible inner logic leading inexorably to mass murder, the consensus among historians today is that when the Nazi regime came to power in January 1933 it had no clear idea how the so-called Jewish problem might best be solved. It knew only that, from its perspective, Jews presented a problem that would need to be solved sooner or later, but finding a long-term solution was initially not one of the regime's most immediate priorities. Between 1933-41 various Nazi agencies proposed different schemes for dealing with Jews. -

Polish Jewry: a Chronology Written by Marek Web Edited and Designed by Ettie Goldwasser, Krysia Fisher, Alix Brandwein

Polish Jewry: A Chronology Written by Marek Web Edited and Designed by Ettie Goldwasser, Krysia Fisher, Alix Brandwein © YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, 2013 The old castle and the Maharsha synagogue in Ostrog, connected by an underground passage. Built in the 17th century, the synagogue was named after Rabbi Shmuel Eliezer Eidels (1555 – 1631), author of the work Hidushei Maharsha. In 1795 the Jews of Ostrog escaped death by hiding in the synagogue during a military attack. To celebrate their survival, the community observed a special Purim each year, on the 7th of Tamuz, and read a scroll or Megillah which told the story of this miracle. Photograph by Alter Kacyzne. YIVO Archives. Courtesy of the Forward Association. A Haven from Persecution YIVO’s dedication to the study of the history of Jews in Poland reflects the importance of Polish Jewry in the Jewish world over a period of one thou- sand years, from medieval times until the 20th century. In early medieval Europe, Jewish communities flourished across a wide swath of Europe, from the Mediterranean lands and the Iberian Peninsu- la to France, England and Germany. But beginning with the first crusade in 1096 and continuing through the 15th century, the center of Jewish life steadily moved eastward to escape persecutions, massacres, and expulsions. A wave of forced expulsions brought an end to the Jewish presence in West- ern Europe for long periods of time. In their quest to find safe haven from persecutions, Jews began to settle in Poland, Lithuania, Bohemia, and parts of Ukraine, and were able to form new communities there during the 12th through 14th centuries. -

Download Paper (PDF)

In the Shadow of the holocauSt the changing Image of German Jewry after 1945 Michael Brenner In the Shadow of the Holocaust The Changing Image of German Jewry after 1945 Michael Brenner INA LEVINE ANNUAL LECTURE 31 JANUARY 2008 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the author. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First Printing, August 2010 Copyright © 2010 by Michael Brenner THE INA LEVINE INVITATIONAL SCHOLAR AWARD, endowed by the William S. and Ina Levine Foundation of Phoenix, Arizona, enables the Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies to bring a distinguished scholar to the Museum each year to conduct innovative research on the Holocaust and to disseminate this work to the American public. The Ina Levine Invitational Scholar also leads seminars, lectures at universities in the United States, and serves as a resource for the Museum, educators, students, and the general public. At its first postwar congress, in Montreux, Switzerland, in July 1948, the political commission of the World Jewish Congress passed a resolution stressing ―the determination of the Jewish people never again to settle on the bloodstained soil of Germany.‖1 These words expressed world Jewry‘s widespread, almost unanimous feeling about the prospect of postwar Jewish life in Germany. And yet, sixty years later, Germany is the only country outside Israel with a rapidly growing Jewish community. Within the last fifteen years its Jewish community has quadrupled from 30,000 affiliated Jews to approximately 120,000, with at least another 50,000 unaffiliated Jews. How did this change come about? 2 • Michael Brenner It belongs to one of the ironies of history that Germany, whose death machine some Jews had just escaped, became a center for Jewish life in post-war Europe. -

El Caso De La Comunidad Judía Mexicana. El Diseño Estructural Del Estado Durante El Siglo Xx Y Su Interrelación Con Las Minorías

El caso dE la comunidad judía mExicana El disEño Estructural dEl Estado durantE El siglo xx y su intErrElación con las minorías 1 © 2009 El caso de la comunidad judía mexicana. El diseño estructural del Estado durante el siglo xx y su interrelación con las minorías Consejo Nacional para Prevenir la Discriminación Dante núm. 14, col. Anzures, Del. Miguel Hidalgo, 11590, México, df Edición: Juan Manuel Ramírez Vélez Fotografias: Antonio Saavedra Diseño y cuidado editorial Atril, Excelencia Editorial “Colección dime”, isbn: 978- 607- 7514- 21-3 Libro “El caso de la comunidad judia mexicana” isbn: 978- 607-7514- 22-0 Se permite la reproducción total o parcial del material incluido en esta obra, previa autorización escrita por parte de la institución. Ejemplar gratuito, prohibida su venta. Impreso en México Printed in Mexico Índice PresentaCión 5 introducción 7 ¿Qué es el judaísmo? 11 los orígenes modernos del judaísmo 23 en méxiCo y los ProCesos de ConsolidaCión instituCional la inserCión de los judíos 39 en los modelos eConómiCos naCionales la PolítiCa naCional y la esCasa 53 PartiCiPaCión judía CamPo de las rePresentaCiones 81 instituCionales gruPales CamPo eduCativo 93 CamPo religioso 111 ConClusiones y reComendaCiones 131 glosario 143 bibliografía 153 PrEsEntación A través de innumerables generaciones, también nosotros hemos experimentado este cambio de estaciones. Walter benjamin Como afirmaba engels, la historia es un prolongado registro de iniquidades y desencuentros, paridos por la violencia. A pesar de tan abundante material, cuando pensamos en una injusticia mayor, en el grado extremo de la exclusión y la intolerancia, nos viene a la mente a la mayoría de nosotras y nosotros el ex- terminio del pueblo judío perpetrado por Hitler y sus secuaces durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. -

Sephardic Family History Research Guide

Courtesy of the Ackman & Ziff Family Genealogy Institute Updated September 2008 Sephardic Family History Research Guide Sephardim Spanish Jews, who had lived on the Iberian Peninsula since 6 B.C.E, began to call themselves Sephardim during the early Middle Ages. After the expulsions from Spain (1492) and Portugal (1497), Jews fled to numerous places within Europe, the Ottoman Empire, and the New World. The word Sephardim came to refer to the Jews of these countries whose origins still remained in Spain or Portugal and who spoke Ladino and other Spanish regional dialects. Sephardic Genealogy Since the Sephardic world is so diverse and widespread, it is difficult to make generalizations about Sephardic genealogy. The sources, methods, and results of genealogical research on a family in Amsterdam, for example, differ greatly from research on a family in Aleppo or Salonika. However, there are several common characteristics: • Sephardic family names are much older than most Ashkenazi names. With Hebraic, Aramaic, Spanish or Arabic roots, Sephardic surnames are often traceable to the 11th century and even earlier. • In Sephardic naming customs, children can be named for both the living and the dead. Often, the firstborn son is named after the paternal grandfather, and the firstborn daughter is named after the paternal grandmother, so that given names may appear in every other generation. Resources at the Center for Jewish History General References Etsi (www.geocities.com/EnchantedForest/1321): journal of Sephardic genealogy (French/English) Genealogy Institute Faiguenboim, Guilherme, Paulo Valadares, and Anna Campagnano. Dicionário Sefaradi de Sobrenomes. (Sao Paulo, Fraiha, 2003) Genealogy Institute CS 3010 .F35 2003 Gandhi, Maneka. -

The Status of Judeo-Spanish in a Diachronic and Synchronic Perspective Includes Six Translated Romances Plus Sample Texts of Biblical Literature and Modern Press

The status of Judeo-Spanish in a diachronic and synchronic perspective Includes six translated Romances plus sample texts of biblical literature and modern press Lester Fernandez Vicet Master thesis in Semitic Linguistics with Hebrew (60 credits) Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages University of Oslo May 2016 Abstract. The speech of the Sephardic Jews have been defined as both language and dialect, depending always on the standpoint of the analyzer, but is it a language on its own right or is it “just a dialect”? What is, then, the difference between both concepts? In the case Judeo-Spanish could be considered a language, what are the criteria taken into account in the classification? In an attempt to answer these questions I will provide facts on the origin of both terms, their modern and politicized use as well as on the historical vicissitudes of Judeo-Spanish and its speakers. Their literature, both laic and religious, is covered with an emphasis on the most researched and relevant genres, namely: the biblical Sephardic translations, the Romancero and the modern press of the 19th Century. A descriptive presentation of Judeo-Spanish main grammatical features precedes the last chapter, where both the diagnosis of Judeo-Spanish in the 20th Century, and its prognosis for the 21st, are given with the aim of determine its present state. Acknowledgements The conception and execution of the present work would have been impossible without the help and support of the persons that were, directly or indirectly, involved in the process. I want to express my gratitude, firstly, to my mentor Lutz E.