'Listen, the Jews Are Ruling Us Now': Antisemitism and National Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antanas Smetona Gimė 1874 M

Antanas Smetona gimė 1874 m. rugpjūčio 10 d. Užulėnio kaime (dab. Ukmergės r.) gausioje neturtingų valstiečių šeimoje. Mokėsi Tau- jėnų pradinėje mokykloje, privačiai – Ukmergėje ir Liepojoje, 1893 m. baigė Palangos progimnaziją. 1896 m. buvo pašalintas iš Mintaujos (dab. Jelgava, Latvija) gimnazijos, nes kartu su kitais lietuviais nepa- kluso reikalavimui, kad katalikai kasdienę maldą mokykloje skaitytų rusiškai. 1897 m. eksternu baigė Peterburgo 9-ąją gimnaziją. Studijavo Peterburgo universiteto Teisės fakultete, priklausė slaptai lietuvių stu- dentų draugijai. Gavęs teisininko diplomą, A. Smetona 1902 m. atvyko į Vilnių, dir- bo advokato padėjėju, vėliau – banke. Jis greit iškilo kaip vienas akty- viausių lietuvių tautinio judėjimo dalyvių. Priklausė Lietuvių demok- ratų partijai. Buvo 1905 m. gruodžio 4–5 d. vykusio Didžiojo Vilniaus Seimo narys, pirmininkavo jo posėdžiui, kuriame svarstytas Lietuvos autonomijos klausimas. A. Smetona dalyvavo daugelio lietuviškų vi- suomeninių, kultūros, švietimo organizacijų – „Aušros“, „Ryto“, „Rū- ANTANAS SMETONA tos“, Lietuvių mokslo ir Lietuvių dailės draugijų – veikloje. Talkino 1874 08 10–1944 01 09 rengiant lietuviškus leidinius: redagavo laikraščius „Vilniaus žinios“, „Lietuvos ūkininkas“, „Viltis“, 1914–1924 m. – žurnalą „Vairas“, paren- gė informacinių ir publicistinių straipsnių tautinės veiklos klausimais. Smetonų šeimos butas Vilniuje buvo lietuvių inteligentų susibūrimų ir diskusijų vieta. Pirmojo pasaulinio karo metais Vilniuje pradėjusi veikti Lietuvių draugija nukentėjusiesiems dėl karo šelpti greit tapo ne tik labdaros organizacija, bet ir lietuvių politinės veiklos centru. Nuo pat įkūrimo organizacijoje dirbęs, o 1914 m. pabaigoje jos Centro komiteto vado- vu tapęs A. Smetona rūpinosi, kad kraštą okupavusios Vokietijos val- džios sprendimai kuo mažiau alintų Lietuvos žmones. 1916 m. kartu su Steponu Kairiu ir Jurgiu Šauliu dalyvavo Trečiajame pavergtųjų tautų kongrese. -

NEWSLETTER Winter/ Spring 2020 LETTER from the DIRECTOR

YIVO Institute for Jewish Research NEWSLETTER winter/ spring 2020 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Friends, launch May 1 with an event at the National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. YIVO is thriving. 2019 was another year of exciting growth. Work proceeded on schedule for the Edward Other highlights include a fabulous segment on Mashable’s Blank YIVO Vilna Online Collections and we anticipate online “What’s in the Basement?” series; a New York completion of this landmark project in December 2021. Times feature article (June 25, 2019) on the acquisition Millions of pages of never-before-seen documents and of the archive of Nachman Blumenthal; a Buzzfeed rare or unique books have now been digitized and put Newsletter article (December 22, 2019) on Chanukah online for researchers, teachers, and students around the photos in the DP camps; and a New Yorker article world to read. The next important step in developing (December 30, 2019) on YIVO’s Autobiographies. YIVO’s online capabilities is the creation of the Bruce and Francesca Cernia Slovin Online Museum of East YIVO is an exciting place to work, to study, to European Jewish Life. The museum will launch early explore, and to reconnect with the great treasures 2021. The first gallery, devoted to the autobiography of the Jewish heritage of Eastern Europe and Russia. of Beba Epstein, is currently being tested. Through Please come for a visit, sign up for a tour, or catch us the art of storytelling the museum will provide the online on our YouTube channel (@YIVOInstitute). historical context for the archive’s vast array of original documents, books, and other artifacts, with some materials being translated to English for the first time. -

Questions to Russian Archives – Short

The Raoul Wallenberg Research Initiative RWI-70 Formal Request to the Russian Government and Archival Authorities on the Raoul Wallenberg Case Pending Questions about Documentation on the 1 Raoul Wallenberg Case in the Russian Archives Photo Credit: Raoul Wallenberg’s photo on a visa application he filed in June 1943 with the Hungarian Legation, Stockholm. Source: The Hungarian National Archives, Budapest. 1 This text is authored by Dr. Vadim Birstein and Susanne Berger. It is based on the paper by V. Birstein and S. Berger, entitled “Das Schicksal Raoul Wallenbergs – Die Wissenslücken.” Auf den Spuren Wallenbergs, Stefan Karner (Hg.). Innsbruck: StudienVerlag, 2015. S. 117-141; the English version of the paper with the title “The Fate of Raoul Wallenberg: Gaps in Our Current Knowledge” is available at http://www.vbirstein.com. Previously many of the questions cited in this document were raised in some form by various experts and researchers. Some have received partial answers, but not to the degree that they could be removed from this list of open questions. 1 I. FSB (Russian Federal Security Service) Archival Materials 1. Interrogation Registers and “Prisoner no. 7”2 1) The key question is: What happened to Raoul Wallenberg after his last known presence in Lubyanka Prison (also known as Inner Prison – the main investigation prison of the Soviet State Security Ministry, MGB, in Moscow) allegedly on March 11, 1947? At the time, Wallenberg was investigated by the 4th Department of the 3rd MGB Main Directorate (military counterintelligence); -

Vincas Kudirka, Martynas Jankus, Jonas Šliūpas and the Making of Modern Lithuania Charles C

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Summer 2013 Lithuanians in the Shadow of Three Eagles: Vincas Kudirka, Martynas Jankus, Jonas Šliūpas and the Making of Modern Lithuania Charles C. Perrin Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Perrin, Charles C., "Lithuanians in the Shadow of Three Eagles: Vincas Kudirka, Martynas Jankus, Jonas Šliūpas and the Making of Modern Lithuania." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2013. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/35 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LITHUANIANS IN THE SHADOW OF THREE EAGLES: VINCAS KUDIRKA, MARTYNAS JANKUS, JONAS ŠLIŪPAS AND THE MAKING OF MODERN LITHUANIA by CHARLES PERRIN Under the Direction of Hugh Hudson ABSTRACT The Lithuanian national movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was an international phenomenon involving Lithuanian communities in three countries: Russia, Germany and the United States. To capture the international dimension of the Lithuanian na- tional movement this study offers biographies of three activists in the movement, each of whom spent a significant amount of time living in one of -

Valentinas Gustainis. Bibliografijos Rodyklė (1918–2005)

Valentinas Gustainis Valentinas Gustainis G Biobibliografijos rodyklė – Biobibliografijos rodyklė ( – ) Valentinas GUSTAINIS Biobibliografijos rodyklë (1918–2005) VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETO BIBLIOTEKA LIGIJA VANAGAITË Valentinas GUSTAINIS Biobibliografijos rodyklë (1918–2005) VILNIAUS UNIVERSITETO LEIDYKLA 2006 UDK 070(474.5):929Gustainis Gu245 Redaktoriø kolegija BIRUTË BUTKEVIÈIENË (pirmininkë) Prof. OSVALDAS JANONIS (ats. redaktorius) AUDRONË MATIJOÐIENË ELVYRA URBONAVIÈIENË Nuotraukos ið VALENTINOS GUSTAINYTËS archyvo Virðelio dailininkas GEDIMINAS MARKAUSKAS Maketavo VIDA VAIDAKAVIÈIENË ISBN 9986-19-905-0 © Vilniaus universiteto biblioteka, 2006 Turinys Pratarmë ___ 7 Antanas Rybelis. Belaisvio laisvës filosofija ___ 8 Albinas Vaièiûnas. Þurnalistas, filosofas, Sibiro kankinys ___ 16 Valentino Gustainio gyvenimo ir veiklos datos ___ 20 Valentino Gustainio slapyvardþiai ___ 32 Valentino Gustainio kûryba ___ 34 Knygos ___ 34 Straipsniai ir recenzijos ___ 36 Apie Valentinà Gustainá ir jo kûrybà ___ 94 Iliustracijos ___ 157 Vardø rodyklë ___ 164 Perþiûrëtø periodiniø leidiniø sàraðas ___ 177 6 V ALENTINAS GUSTAINIS Biobibliografijos rodyklë 7 Pratarmë iobibliografijos rodyklë skiriama þymaus Lietuvos þurnalisto, Bsociologo, filosofo Valentino Gustainio 110-osioms gimimo metinëms. V. Gustainis – vienas pirmøjø tarpukario þurnalistø profesionalø. Jo visas gyvenimas, kûrybinë ir visuomeninë veikla, prasidëjusi pirmaisiais Nepriklausomybës metais, susieta su Vals- tybës likimu. Ði rodyklë – tai pirmas bandymas surinkti ir apraðyti tarpukario -

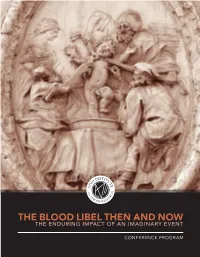

Read the Conference Program

COVER: Stone medallion with the purported martyrdom scene of Simonino di Trento. Palazzo Salvadori, Trent, Italy. Photo by Andreas Caranti. Via Wikimedia Commons. YIVO INSTITUTE FOR JEWISH RESEARCH PRESENTS CONFERENCE OCTOBER 9, 2016 CO-SPONSORED BY 1 INCE ITS FABRICATION IN THE MIDDLE AGES, the accusation that Jews Skidnapped, tortured and killed Christian children in mockery of Christ and the Crucifixion, or for the use of their blood, has been the basis for some of the most hateful examples of organized antisemitism. The blood libel has inspired expulsions and murder of Jews, tortures and forced mass conversions, and has served as an ines- capable focal point for wider strains of anti-Jewish sentiment that permeate learned and popular discourse, social and political thought, and cultural media. In light of contemporary manifestations of antisemitism around the world it is appropriate to re-examine the enduring history, the wide dissemination, and the persistent life of a historical and cultural myth—a bald lie—intended to demonize the Jewish people. This conference explores the impact of the blood libel over the centuries in a wide variety of geographic regions. It focuses on cultural memory: how cultural memory was created, elaborated, and transmitted even when based on no actual event. Scholars have treated the blood libel within their own areas of expertise—as medieval myth, early modern financial incentive, racial construct, modern catalyst for pogroms and the expulsion of Jews, and political scare tactic—but rarely have there been opportunities to discuss such subjects across chronological and disciplinary borders. We will look at the blood libel as historical phenomenon, legal justification, economic mechanism, and visual and literary trope with ongoing political repercussions. -

Antanas Smetona

Antanas Smetona Bibliografijos rodyklė (1935–2016) Leidinio sudarytojos: Zina DAUGĖLAITĖ, Irena ADOMAITIENĖ Redaktorės: Gražina RINKEVIČIENĖ, Regina KNEIŽYTĖ Kalbos redaktorė Lina ŠILAGALIENĖ Maketuotojas Tomas RASTENIS Viršelio nuotr. iš leid.: 1918 m. vasario 16 d. Lietuvos Nepriklausomybės Akto signatarai. V., 2006. Leidinio bibliografinė informacija pateikiama Lietuvos nacionalinės Martyno Mažvydo bibliotekos Nacionalinės bibliografijos duomenų banke (NBDB) 2019 04 03. 21 leidyb. apsk. l. Išleido Lietuvos nacionalinė Martyno Mažvydo biblioteka Gedimino pr. 51, LT-01504 Vilnius ISBN 978-609-405-179-1 Turinys Turinys 1954 metai ..........................................................................................................70 1955 metai ..........................................................................................................70 Turinys ................................................................................................................................... 3 1956 metai ..........................................................................................................70 1958 metai ..........................................................................................................71 Pratarmė ............................................................................................................................... 6 1969 metai ..........................................................................................................71 Biografija ............................................................................................................................. -

JUL 15 and the History of YIVO CECILE KUZNITZ | Delivered in English

MONDAY The Rise of Yiddish Scholarship JUL 15 and the History of YIVO CECILE KUZNITZ | Delivered in English As Jewish activists sought to build a modern, secular culture in the late nineteenth century they stressed the need to conduct research in and about Yiddish, the traditionally denigrated vernacular of European Jewry. By documenting and developing Yiddish and its culture, they hoped to win respect for the language and rights for its speakers as a national minority group. The Yidisher visnshaftlekher institut [Yiddish Scientific Institute], known by its acronym YIVO, was founded in 1925 as the first organization dedicated to Yiddish scholarship. Throughout its history, YIVO balanced its mission both to pursue academic research and to respond to the needs of the folk, the masses of ordinary Yiddish- speaking Jews. This talk will explore the origins of Yiddish scholarship and why YIVO’s work was seen as crucial to constructing a modern Jewish identity in the Diaspora. Cecile Kuznitz is Associate Professor of Jewish history and Director of Jewish Studies at Bard College. She received her Ph.D. in modern Jewish history from Stanford University and previously taught at Georgetown University. She has held fellowships at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies, and the Center for Advanced Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. In summer 2013 she was a Visiting Scholar at Vilnius University. She is the author of several articles on the history of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, the Jewish community of Vilna, and the field of Yiddish Studies. English-Language Bibliography of Recent Works on Yiddish Studies CECILE KUZNITZ Baker, Zachary M. -

Valstiečiai Liaudininkai Lietuvos Politiniame Gyvenime 1926 –1940 M

VYTAUTO DIDŽIOJO UNIVERSITETAS LIETUVOS ISTORIJOS INSTITUTAS Mindaugas TAMOŠAITIS VALSTIEČIAI LIAUDININKAI LIETUVOS POLITINIAME GYVENIME 1926 –1940 M. Daktaro disertacija Humanitariniai mokslai, istorija (05H) Kaunas, 2011 UDK 329(474.5) Ta-79 Disertacija ginama eksternu Doktorantūros teisė suteikta Vytauto Didžiojo universitetui kartu su Lietuvos istorijos institutu 2003 m. liepos 15 d. Lietuvos Respublikos Vyriausybės nutarimu Nr. 926. Mokslinis konsultantas: Doc. dr. Pranas Janauskas (Vytauto Didžiojo universitetas, Humanitariniai mokslai, istorija – 05H) ISBN 978-9955-12-665-2 2 TURINYS ĮVADAS .......................................................................................................................................4 I. BENDRA POLITINĖ SITUACIJA IR VALSTIEČIŲ PARTIJŲ PADĖTIS VIDURIO RYTŲ EUROPOJE................................................................................................29 II. VALSTIEČIAI LIAUDININKAI IR LIETUVOS VALDŽIOS POLITIKA (IKI 1929 M) ..............................................................................................................................39 III. PARTIJOS VIDAUS PROBLEMOS ...............................................................................59 1. Organizacinės struktūros raidos ypatumai ..............................................................................59 2. Pozicijų skirtumai partijoje (4-ojo dešimtmečio I-oji pusė) ..................................................82 3. Kartų konfliktas 4-ame dešimtmetyje ...................................................................................115 -

Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence

Russia • Military / Security Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 5 PRINGLE At its peak, the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti) was the largest HISTORICAL secret police and espionage organization in the world. It became so influential DICTIONARY OF in Soviet politics that several of its directors moved on to become premiers of the Soviet Union. In fact, Russian president Vladimir V. Putin is a former head of the KGB. The GRU (Glavnoe Razvedvitelnoe Upravleniye) is the principal intelligence unit of the Russian armed forces, having been established in 1920 by Leon Trotsky during the Russian civil war. It was the first subordinate to the KGB, and although the KGB broke up with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the GRU remains intact, cohesive, highly efficient, and with far greater resources than its civilian counterparts. & The KGB and GRU are just two of the many Russian and Soviet intelli- gence agencies covered in Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence. Through a list of acronyms and abbreviations, a chronology, an introductory HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF essay, a bibliography, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries, a clear picture of this subject is presented. Entries also cover Russian and Soviet leaders, leading intelligence and security officers, the Lenin and Stalin purges, the gulag, and noted espionage cases. INTELLIGENCE Robert W. Pringle is a former foreign service officer and intelligence analyst RUSSIAN with a lifelong interest in Russian security. He has served as a diplomat and intelligence professional in Africa, the former Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe. For orders and information please contact the publisher && SOVIET Scarecrow Press, Inc. -

Lithuanians and Poles Against Communism After 1956. Parallel Ways to Freedom?

Lithuanians and Poles against Communism after 1956. Parallel Ways to Freedom? The project has been co-financed by the Department of Public and Cultural Diplomacy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs within the competition ‘Cooperation in the field of public diplomacy 2013.’ The publication expresses only the views of the author and must not be identified with the official stance of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The book is available under the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0, Poland. Some rights have been reserved to the authors and the Faculty of International and Po- litical Studies of the Jagiellonian University. This piece has been created as a part of the competition ‘Cooperation in the Field of Public Diplomacy in 2013,’ implemented by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2013. It is permitted to use this work, provided that the above information, including the information on the applicable license, holders of rights and competition ‘Cooperation in the field of public diplomacy 2013’ is included. Translated from Polish by Anna Sekułowicz and Łukasz Moskała Translated from Lithuanian by Aldona Matulytė Copy-edited by Keith Horeschka Cover designe by Bartłomiej Klepiński ISBN 978-609-8086-05-8 © PI Bernardinai.lt, 2015 © Jagiellonian University, 2015 Lithuanians and Poles against Communism after 1956. Parallel Ways to Freedom? Editet by Katarzyna Korzeniewska, Adam Mielczarek, Monika Kareniauskaitė, and Małgorzata Stefanowicz Vilnius 2015 Table of Contents 7 Katarzyna Korzeniewska, Adam Mielczarek, Monika Kareniauskaitė, Małgorzata -

In the European Parliament Laure Neumayer

Integrating the Central European Past into a Common Narrative: the mobilizations around the ’crimes of Communism’ in the European Parliament Laure Neumayer To cite this version: Laure Neumayer. Integrating the Central European Past into a Common Narrative: the mobilizations around the ’crimes of Communism’ in the European Parliament. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, Taylor & Francis (Routledge), 2015. hal-03023744 HAL Id: hal-03023744 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03023744 Submitted on 25 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Integrating the Central European Past into a Common Narrative: the mobilizations around the ‘crimes of Communism’ in the European Parliament LAURE NEUMAYER Université Paris 1 Panthéon Sorbonne and Institut Universitaire de France, France ABSTRACT: After the Cold War, a new constellation of actors entered transnational European assemblies. Their interpretation of European history, which was based on the equivalence of the two ‘totalitarianisms’, Stalinism and Nazism, directly challenged the prevailing Western European narrative constructed on the uniqueness of the Holocaust as the epitome of evil. This article focuses on the mobilizations of these memory entrepreneurs in the European Parliament in order to take into account the issue of agency in European memory politics.